Urban farmer, teacher and regenerative advocate in Aotearoa, New Zealand, Sarah Hopkinson reckons with her history, the space of Taranaki and looks for links of compassion and love to find a future for dairy farming.

The white tears of Taranaki

Words by Sarah Alice Hopkinsonartwork by Cat O’Neilaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Article

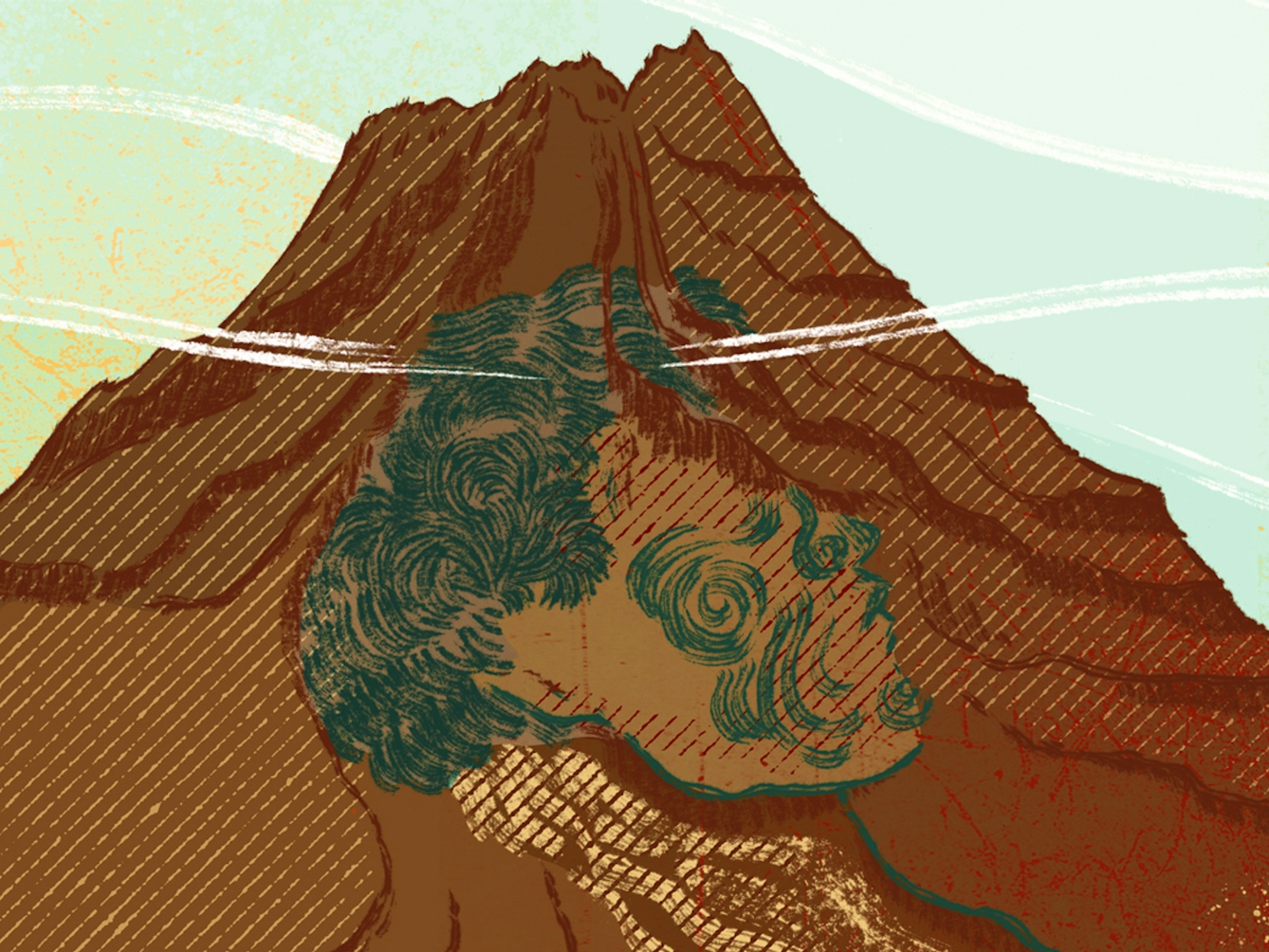

I was born and grew up at the ankles of the great mountain Taranaki on the west coast of the North Island of Aotearoa, New Zealand. This is dairy country, and this is my love story.

Taranaki is as majestic as a mountain could possibly be. He rises up, almost urgently, from near sea level to over 2,500 m (8,200 feet). He is a mighty sight on a clear day – a nearly perfect conical shape with snow atop for most of the year. When I return home, I bow my head and greet him like a loved one. When I am away, I yearn for his presence behind my shoulder.

My ancestors arrived here on a settler ship, the ‘Clifton’, in 1842. I am Pākehā – a New Zealand-born European. When asked where I am from, I used to say: “Taranaki.”

A tidy story of me, which starts in the 1840s and has been ‘New Zealander’ ever since. A straightforward tale that completely ignores the stark fact that I am half a world away from all my ancestors’ bones and rituals, their seasons and stories.

But my ‘Pākehā-ness’ comes from many beautiful places that are far from this mountain. Blood runs in me from landed gentry in Sussex, Kent and Berkshire. It runs from an ordinary hill in Wales, from a clifftop near Dingle in Ireland, and from a scrap of Norway that I will not be able to find. And if I lean in long enough here, with all these places running deep inside me, I know there was a time – back in the somewhen – when my people had an abiding love for the land under their feet.

“When I return home, I bow my head and greet him like a loved one. When I am away, I yearn for his presence behind my shoulder.”

It’s not really like that any more. Hold on and I will tell you what we did to this land, and in turn, to ourselves.

But first I need to tell you that Taranaki is, and always was, Māori land. This is the land of Ngāti Tama, Ngāti Maru and Ngāti Mutunga in the north, Te Atiawa and Taranaki in the west and Ngā Ruahine, Ngāti Ruanui, and Ngāti Rauru in the south. Māori did not cede sovereignty to the British Crown and the New Zealand Wars raged here.

When it became clear that the colonial government was not going to win easily, the Crown changed tack and went through the courts. They confiscated the entire region of Taranaki – 1.2 million acres of land – as punishment, raupatu, for Māori defending their home.

So yeah, this is where I am from.

Most Pākehā want to claim our geographical ties without the historical ones. Want to say that we are from Taranaki, with its rolling green pastures and calm dairy herds, without the accompanying story of violence. But the two histories belong together – my people’s story in Taranaki didn’t start so much with the milk flowing as with the muskets firing.

Dairy queen

Today, this region is a jewel in the crown of this dairyland, Aotearoa.

In Taranaki, milk flows in simply epic proportions. On the grassy fields that now surround the mountain slopes, cow herd after cow herd graze. Tankers drive the region’s highway, collecting and delivering “white gold” to Whareroa, home to the largest dairy factory in the world, which processes about 14 million litres of milk per day.

“Māori did not cede sovereignty to the British Crown and the New Zealand Wars raged here.“

The Whareroa factory is owned by Fonterra, in turn the largest company in our country, responsible for 30 per cent of all of the world’s dairy exports and NZ$22 billion of New Zealand’s yearly exports. Each and every year, the factory produces 428,000 tonnes of milk powders, cheeses, creams and proteins.

My people’s story in Taranaki didn’t start so much with the milk flowing as with the muskets firing.

It’s an unfathomable amount of dairy. Equivalent to the weight of 61,000 adult male elephants. Although we aren’t used to seeing one elephant, let alone 61,000, let’s just agree on one thing, it’s a heck of a lot of milk.

I think there is a deep knowing, within all of us, wherever we are, that this scale of food production, this size of monoculture, regardless of what is being produced, is, at the heart of it, unsustainable. We all have a sense, if we stop still long enough and listen to the aliveness that runs in us, that this level and size of industry, this hurts our earth.

I want to tend to the spiritual cost of separating food production from our shared lives. The spiritual cost of 61,000 elephants of milk coming from the paddocks of Taranaki every year.

I am the river, and the river is me

As Pākehā, longing to speak to the spiritual cost of disconnection feels as dangerous as it is necessary. There is a real tightrope to walk – one foot acknowledging that Pākehā are in receipt of great material advantage as a result of colonising this land, and another foot (which feels a whole lot more ginger) that wants to venture that colonisation, and its associated practices, has fundamentally hurt us as well.

You see, my people have forgotten the inalienable truth that we are home. That this earth below us, she is our sustainer. This collective amnesia has resulted in an extractive form of capitalism in this land that is deeply disconnected from life itself. And perhaps the climate crisis is the natural-born grandchild of this great forgetting which we see the world over.

Maybe most alarming, here in Taranaki, is that we have created a whole industry around milk alone. This myopia ignores the fact that nature, above all else, is deeply diverse and if there’s any enemy to life itself, it is monoculture. I don’t want to minimise the complexities of turning global food systems into localised, diverse ones. But I do want to say that the way we understand nature, the way we grow, connect, love and share our food: it fundamentally matters.

“We all have a sense, if we stop still long enough and listen to the aliveness that runs in us, that this level and size of industry, this hurts our earth.”

The principles that underpin Māori knowledge systems provide many wayfaring signs for more restorative ways of being. In te ao Māori (the Māori world) there is a whakataukī (proverb),

Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au.

I am the river, and the river is me.

This recognition that we are only as well as the world that surrounds us feels exceedingly relevant to this contemporary dairy moment. Within this whakataukī there is also recognition of the reciprocity that exists when we cultivate meaningful relationships with this planet. As a grower myself, regenerating an organic food landscape in a suburban setting, I have felt this two-way street keenly.

In my ancestral tapestry, my kin knew this too. I have to believe that those ancient threads still run through us all.

The value sets that colonised this land have also brought us to this moment. Clearly all is not well. As hard as it is to imagine a world that is decoupled from global trade, there is nothing inevitable about the systems that we work within. Our waterways, our soil, our animals, all of which is our-selves, need us to reimagine a new future.

I can see my Uncle Dave, a dairy farmer, a bloody good one too, getting hurrumpy. “I am doing my best,” I can picture him saying. And he is. There are many loving farmers trapped inside really badly designed systems. We all are.

I’ve no idea what to do next about the 61,000 elephants of milk coming from Taranaki, but as Joanna Macy, a deep ecologist, so powerfully writes: “Of all the dangers we face, from climate chaos to nuclear war, none is so great as the deadening of our response.”

I am listening to the longing that is within me.

I am listening to the deep knowing in me too – which is the deep knowing in you as well, which is the deep knowing in this earth, which in the end, is the deep knowing in us all.

About the contributors

Sarah Alice Hopkinson

Sarah Alice Hopkinson is a consultant, urban farmer, earth dreamer and regeneration advocate. She has committed the last 20 years to addressing social and environmental justice issues in New Zealand Aotearoa schools. She farms regeneratively at the Green Garden, a suburban farm on Te Ātiawa ki Whakarongotai land, growing nutrient-dense food for her family and community, and is on the advisory board of For the Love of Bees, who are growing radical hope through food.

Cat O’Neil

Cat O’Neil is an award-winning freelance illustrator, specialising in editorial. She studied at the Edinburgh College of Art, graduating in 2011, and has lived in Hong Kong, London, Glasgow, Lyon and Edinburgh. Her clients include the New York Times, Washington Post, WIRED, LA Times, Scientific American, the Financial Times, the Guardian/Observer, Libération and more. Her work explores the use of visual metaphors to convey concept and narrative, and combines the use of traditional and digital mediums. Much of her recent work includes the creation of 3D paper sculptures, which are made in her studio in Edinburgh.