For Georgie Evans, hoarding seems simultaneously invisible and everywhere. The more digging she does, the more slippery a subject it becomes. As she tries to explain the intensity of her grandma’s collecting, Georgie examines the tools available to describe and diagnose hoarding behaviour – and finds them lacking.

I don’t remember if Grandma’s doctor was the first person to call her a hoarder, or if someone else used the word first. Grandma doesn’t remember either: when I ask, she’s not sure what it means.

Hoarding – it feels so far from what she’s been doing all these years. She’s been preserving, protecting, trying to keep control. No one taught her, or tried much to convince her, that there was a word and reasons for all the stuff; possibly some support to be found, too. And it doesn’t help that Grandma is stubborn.

I want to look at the language we have for all this, the endless collecting, since that is where it feels furthest from my grandma. The Oxford English Dictionary defines ‘hoard’ as:

hoard (n.)

1. a supply or fund stored up and often hidden away

hoard (v.)

1. transitive verb: to collect and often hide away a supply of; to keep to oneself

2. intransitive verb: to collect and often hide away a supply of something; specifically, to engage in compulsive hoarding

The word is related to the Old English words hord, meaning ‘treasure’, and hȳden, meaning ‘to hide’. Hiding, storing, supplying, treasuring, collecting – we haven’t much changed our meanings of the word. Except now we have added a new meaning; one that buries deeper.

The World Health Organization describes hoarding disorder as “the accumulation of possessions due to excessive acquisition of or difficulty discarding possessions, regardless of their actual value”. It says the symptoms result in “significant distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning”.

A dearth of diagnoses

I reach out to Megan Carnes, who set up the charity HoardingUK, to ask her about the words, classifications, and limits of hoarding. I join the call expecting a conversation about medical lore, but I soon see that Megan’s work has shown her a more real, desperate view of hoarding.

When I ask about diagnosis, she’s quick to tell me that few people who approach HoardingUK for help have got one. “What we know is, across the UK very few statutory organisations have a box that says hoarding. We don’t have any real figures.”

I notice she uses the phrase “hoarding behaviour”, rather than “hoarding disorder”. Is it because of the issue with diagnosis? She nods. “We don’t need people to call themselves a person with hoarding behaviour either. If they’re in trouble because of things in their space… we’ll help.”

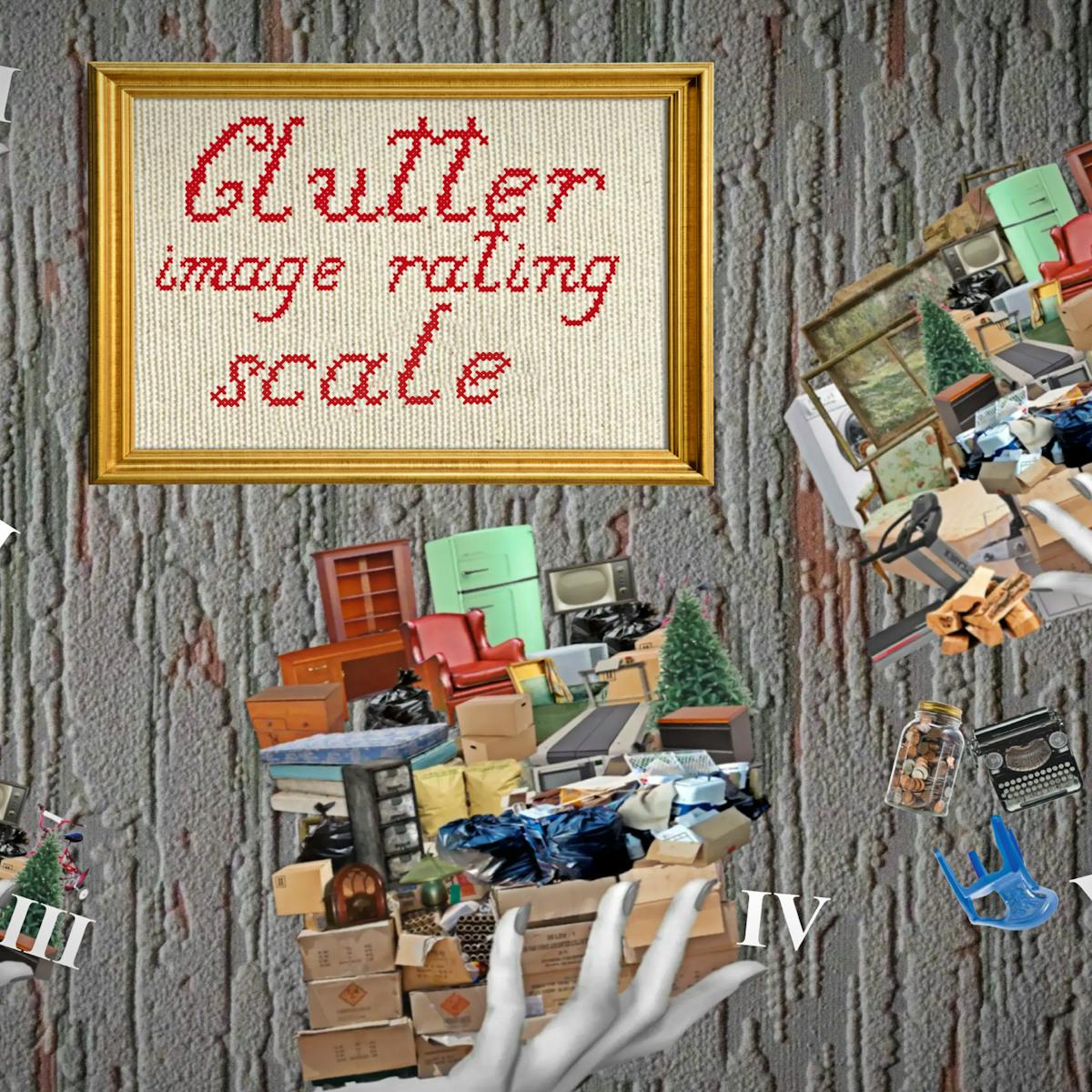

How to measure clutter

Megan tells me about a tool that is often used for distinguishing hoarding from less concerning levels of untidiness: the Clutter Image Rating. It was devised by the International OCD Foundation as a way of measuring the level of hoarding someone is living with. There is a series of nine photographs, all of the same room, and the level of messiness increases between each photo. It makes sense as a non-subjective way of measuring hoarding.

“I see that hoarding is simultaneously invisible and everywhere.”

From what I remember, Grandma was probably a 6 or a 7 when her collecting was at its most intense. There were a lot of times we’d visit, having only seen her a day or two before, and the house would have stretched and the stuff multiplied. I was almost impressed with how quickly Grandma could accumulate things.

The OCD Foundation recommends seeking professional help for anything above a 4 on the Clutter Image Rating. My grandma never received professional help.

I see that hoarding is simultaneously invisible and everywhere. There are no real figures on how many people hoard in the UK, but Megan and I talk about how everyone seems to know someone who does it. It’s true: when I told people I was writing about hoarding, they would tell me to speak to their dad, their auntie, their neighbour.

But it’s difficult to get a diagnosis or to access support. The medical classification seems to be rarely referred to and I struggle to find solid information on what and who makes a hoarder. The words Megan uses start to liken her work to a hidden war; twice she refers to “what’s happening out there” and it makes me think of a battlefield.

There are no real figures on how many people hoard in the UK, but everyone seems to know someone who does it.

I’m suddenly overwhelmed with the scale and effect of hoarding. I don’t understand why there seem to be few resources and little real effort to help. People are fighting their own habits and compulsions, while having to fight the people who step in, in unproductive ways. You can’t tidy a hoarder’s kitchen and have that be the end of it.

“The Clutter Image Rating is helpful, but it also doesn’t allow for any context. If there’s a lot of mess – a large collection – there has to be a reason for it.”

But at the same time, few people know exactly how to help. Because it is so entwined with how people keep their homes, it can be difficult and awkward to use the word ‘hoarding’ with someone. “We’ve got to change the voice of this,” Megan tells me as we’re saying goodbye. “We’ve got to stop it being about cluttered rooms.”

I nod and thank her again, and then she’s gone from my computer screen. But for a second I’m confused. How can we shift attention from cluttered rooms completely, when they’re the means of measuring hoarding?

Dementia creeps in

The Clutter Image Rating is helpful, but it also doesn’t allow for any context. If there’s a lot of mess – a large collection – there has to be a reason for it. Something else must be happening: something internal, emotional. Otherwise, we could say that someone who collected vintage cars is a hoarder.

I don’t remember Grandma – or anyone else, really – using the words “hoarding disorder”. Nothing seemed to change after her doctor suggested that’s what it could be, except that she became less willing to bicker with us when we asked to throw rotten food away.

Something else was happening, which would complicate things: Grandma was starting to forget. Only a little, at first; mixing up my name with my sister’s. Then she was forgetting the day, the month. Who was prime minister. Birthdays next.

That was dementia, slowly gnawing at her. It made us think differently about how and why Grandma was hoarding – and it changed the ways we tried to help her with it.

About the contributors

Georgie Evans

Georgie Evans is a writer and bookseller from Halifax. She has an MA from Goldsmiths University and has published words in Brixton Review of Books, the Rialto, the Pomegranate, and the Telegraph. She is currently working on a hybrid non-fiction book about deafness and dementia.

Nicole Coffield

Nicole Coffield, also known as Collage Graduate, is a digital collage artist based in Northern California. Her work is composed of forgotten ads and images that are reworked to tell a new story.