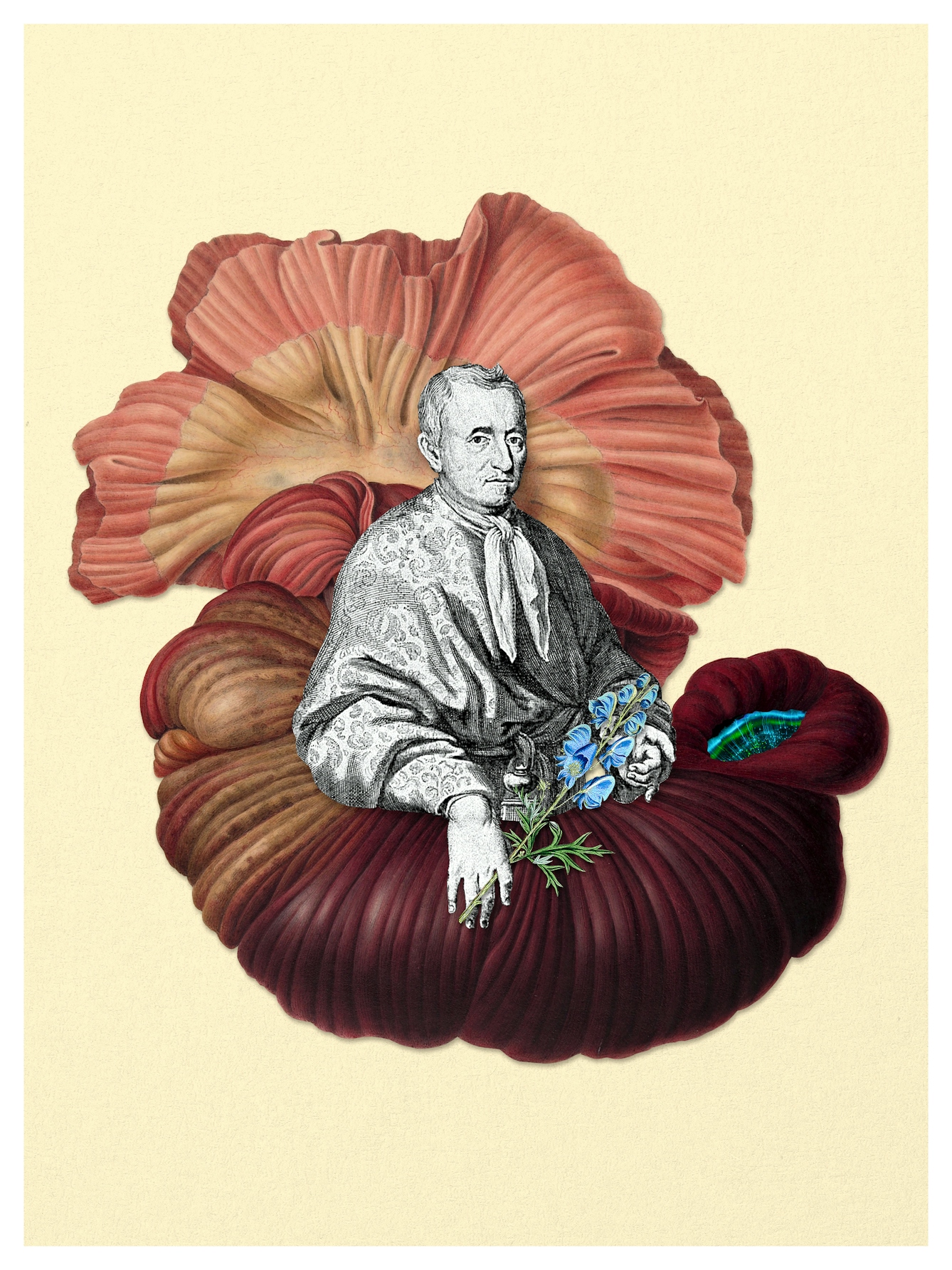

How a 17th-century physician followed his ‘gut feeling’ and proposed a link between the emotions and the stomach, which seemingly echoes the latest medical research on the brain–gut connection.

Sometime in the first half of the 17th century, the alchemist and physician Jan Baptist van Helmont (1580–1644) was spending a fairly typical day in his laboratory conducting experiments on wolfsbane – a highly toxic flower sometimes called the ‘queen of poisons’ – when he was called away from his work to attend to some household business. Later that evening, he began to feel distinctly odd. “I felt,” he wrote, “that I did understand, conceive, savour, or imagine nothing in the head,” but rather, “that I understood and imagined in the midriffs.”

What van Helmont had experienced was, quite literally, a ‘gut feeling’, a powerful sense that his emotions, perceptions, and perhaps even his whole identity were somehow inextricably tied to his digestive tract. The experience set van Helmont on a path that would lead to a seemingly bizarre and radical theory.

According to van Helmont(view in catalogue), emotions did not arise in the heart, as ancient philosophy stated. Nor were they located in the brain, despite the growing consensus among university-educated anatomists and physiologists of the time. Rather, he insisted, the processes of emotion, perception and imagination took place in the organs of digestion.

The stomach, he argued, was far more than just a factory for the processing of food. It was, in fact, the seat of that mediator between the physical and the spiritual realms: the sensitive soul.

“Van Helmont was conducting experiments in his laboratory on wolfsbane – a highly toxic flower. Later that evening, he began to feel distinctly odd. He wrote, ‘I... imagine nothing in the head,’ but rather, ... ‘I understood and imagined in the midriffs.’”

Anatomical soul-searching

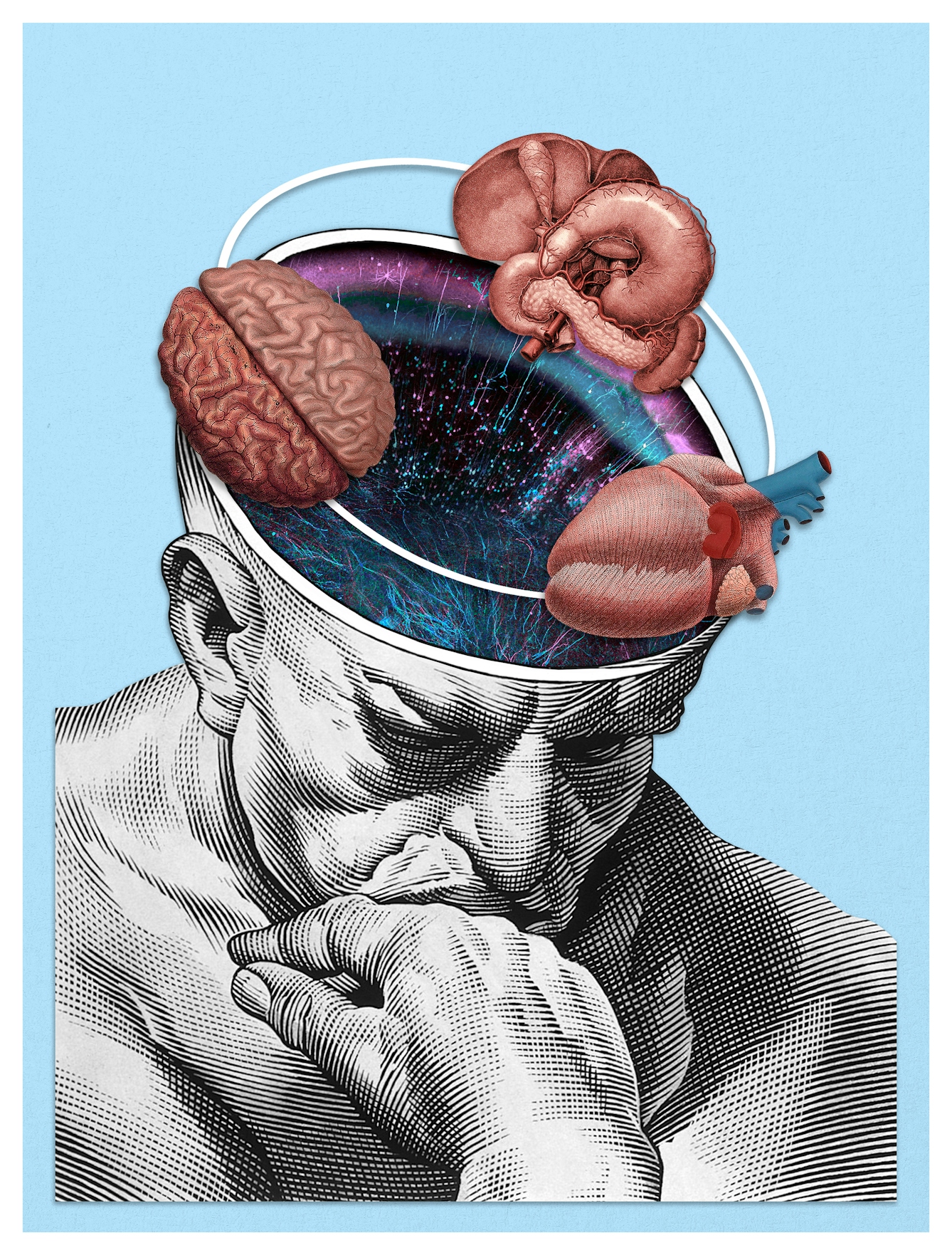

For centuries, European universities had followed ancient Greek thinkers such as Plato, Aristotle and Galen in viewing the human soul as divided into three parts. At the top of this hierarchy was the ‘rational’ soul, located in the brain, which managed intellectual operations: logical reasoning, memory and the power of the will. Below this – situated in the chest or heart – was the ‘sensitive’ soul, governing motion, emotion and sensory perception.

Finally there was the ‘vegetative’ soul, which governed the basic operations necessary to all living organisms: growth, nutrition and reproduction. These processes took place in the ‘lower parts’ – the digestive and reproductive organs – and were often identified with the liver.

The 17th century witnessed several challenges to this classical model of the soul. The French philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650), who was a contemporary of van Helmont, hypothesised that the soul operated on the body through the pineal gland, an organ no bigger than a grain of rice nestled at the centre of the brain.

Scholars and physicians like Descartes and the English physiologist Thomas Willis (1621–75) drew on increasingly detailed anatomical studies of the brain to argue that the operations of the soul took place entirely within the head.

“For centuries, European universities had viewed the soul as divided into three parts, the ‘rational’ soul in the brain, the ‘sensitive’ soul in the heart and the ‘vegetative’ soul in the digestive organs.”

Van Helmont, however, took a quite different approach, despite being acutely aware that many would dismiss the notion of the soul in the stomach as “a mad or foolish idea”. He supported his claims with appeals to popular opinion.

Elite, university-educated physicians, he argued, simply couldn’t ‘stomach’ the idea that the soul might conduct its divine operations from within “a sack of impure meats”. But outside the universities, the “common people” were on his side: ask any peasant or townsperson to identify the seat of the soul, he asserted, and they would “show with the hand, the orifice of the stomach”.

Human experience as medical evidence

In contrast to the leading medical thinkers of his time, many of whom were turning toward detailed anatomical studies and mathematical concepts to seek explanations for physical phenomena, Van Helmont’s theory depended upon appeals to human experiences that could be difficult or even impossible to articulate: “If a gun sends forth a noise unexpectedly,” he observed, “a timorous person, in a sudden terror, feels the token of fear in the mouth of his stomach.”

Similarly, he noted how “if a sorrowful message be brought unto a hungry man, his appetite presently perishes”. But even he was ultimately forced to admit that the sensations he was attempting to describe “cannot by any words be expressed”. It is not entirely surprising, then, that Van Helmont’s theory was largely rejected by the elite scientific circles of his day.

“Over the past decade, research into the gut microbiome and enteric nervous system points to a dynamic and multidirectional relationship between belly and brain.”

One medical encyclopaedist, writing around 1700, dismissed the theory as “a quite different opinion from all the rest”. Van Helmont’s unusual writing style, with his emphasis on religious themes and attentiveness to subjective experience, was out of step with the current thinking of his day, and it seems clear that his “mad or foolish idea” was always doomed to failure.

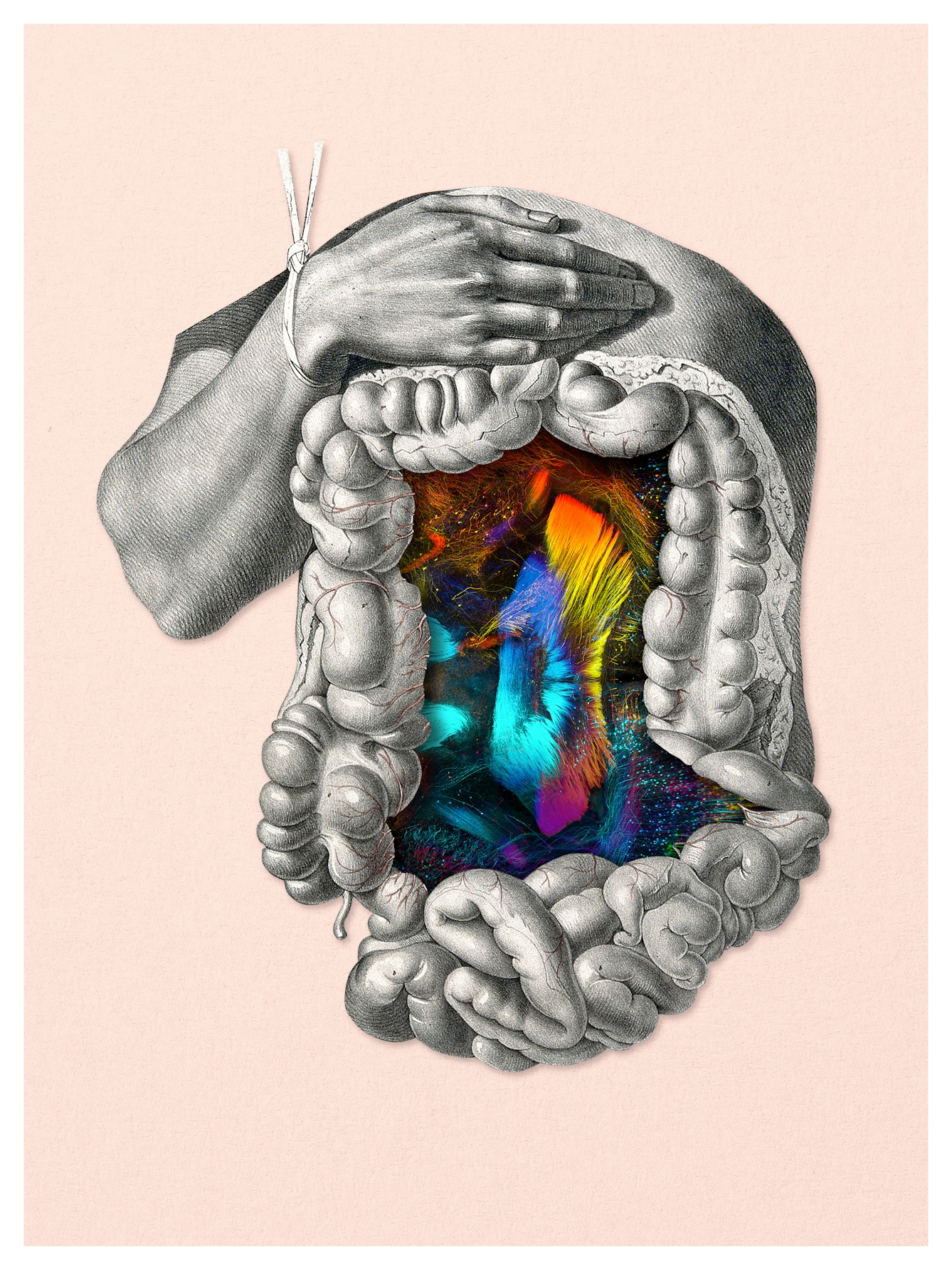

Modern research on the gut

And yet the idea of the digestive organs as a seat of emotional experience no longer seems quite so mad or foolish. Over the past decade, research into the gut microbiome and enteric nervous system points to a dynamic and multidirectional relationship between belly and brain, and scientists are now taking a fresh look at the role of gut health in both mental and physical wellbeing. Once little more than a metaphor, the ‘gut feeling’ might be a medical reality.

Although van Helmont’s theory has no connection to modern scientific research, his story is a reminder that each person has an intuitive relationship with their own body that can be difficult to express, and even more difficult to convey to others. But this doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t still try. Even when our gut feelings seem to be at odds with the knowledge of our day, they might well be able to tell us something about our own bodies that is fundamentally true.

About the contributors

Michael Walkden

Dr Michael Walkden did his PhD on the relationship between mind and gut in early modern English medicine. He is a postdoctoral research fellow on the Folger Shakespeare Library's Before Farm to Table project.

Annemarieke Kloosterhof

Annemarieke is a multidisciplinary illustrator/maker who specialises in all things paper. Originally from the Netherlands, she's been based in London for the past ten years and creates work in 2D, 3D and even 4D. Anything from traditional paper-cutting, collages and illustrations to 3D paper props and large-scale sets for photo and film shoots. Annemarieke enjoys experimenting with vibrant colours, precise details and bold layouts, and enjoys drawing parallels in languages, loves symbolism, colour theory, puns and idioms... which often can be spotted in her work.