Before her brother was born, talking was something Jessica Andrews did without thinking. His profound deafness meant conversations became more tactile and tangible, and revealed language to be a slippery, complicated thing. The author reflects on how signing and subtitles have shaped the writer she has become.

My brother, who is five years younger than me, was born deaf (some people with a hearing loss choose to identify as deaf with a lower-case ‘d’, which is often used when a person does not strongly identify with deaf culture and might communicate orally). He could not hear any frequencies of sound and responded only to vibrations, which made him, the audiologist told my mother, “the most profoundly deaf child I have ever encountered”.

‘Profoundly deaf’ is a medical term, but the word ‘profound’ suggests a gravity that verges on philosophical, an emotional intensity with the power to alter the course of a life.

Before my brother arrived, we used language carelessly, without thinking about it. We shouted to each other in different rooms above the noise of the hoover, the radio, the telly and the washing machine. Speaking was just something that we did.

When my brother was born, language became more tangible. It had a physical presence, its leaves and branches growing through the walls of our house. We learned to be more tactile, touching arms and shoulders, making sure he could see our faces when we spoke. Friends brought toys that flashed and shook; a Bumble Ball and a Tickle Me Elmo. We got a doorbell that made all of the lights in our house strobe, which turned our tea times into frantic discos.

We chose signs for people’s names depending on visual cues. My friend Carly had curly hair, so we shaped the letter ‘C’ spilling from our temples in waves. My cousin, Daniel, who was only a few months old, was assigned the sign for baby, which followed him into adulthood. My new name was created in relation to my brother. Both of our names begin with ‘J’ and his name is a ‘J’ signed in the palm of a hand. Mine is a ‘J’ outlined on the right cheek; our difference traced across hands and faces.

My mother became an interpreter. When I heard her call my name and watched her twist it in her fingers, I understood that both represented me, but that I was also many other things that could not be named so neatly.

At five years old, I learned that there’s more to language than words alone. It felt slippery and complex and I began to see that we are all merely grasping for better ways to understand each other.

"When my brother was born, language became more tangible. We learned to be more tactile, touching arms and shoulders, making sure he could see our faces."

Through sign, we were able to discuss the people around us without them knowing. Strangers often stared at us, in supermarkets and soft plays, while we used our hands to weave a safe, secret space they could not enter. I taught my friends at school how to fingerspell their names and they delighted in having a new way to describe themselves.

We went to church and my brother appeared like an angel in the list of people we should pray for, which gave us an air of celebrity. His difference could have made us fragile, but instead it made us strong.

Introducing the world of sound

When my brother was almost three, he was given a cochlear implant. In 2019, children are implanted from as early as six months, but in 1999 my brother was the 100th person in the James Cook University Hospital in Middlesbrough ever to have an implant.

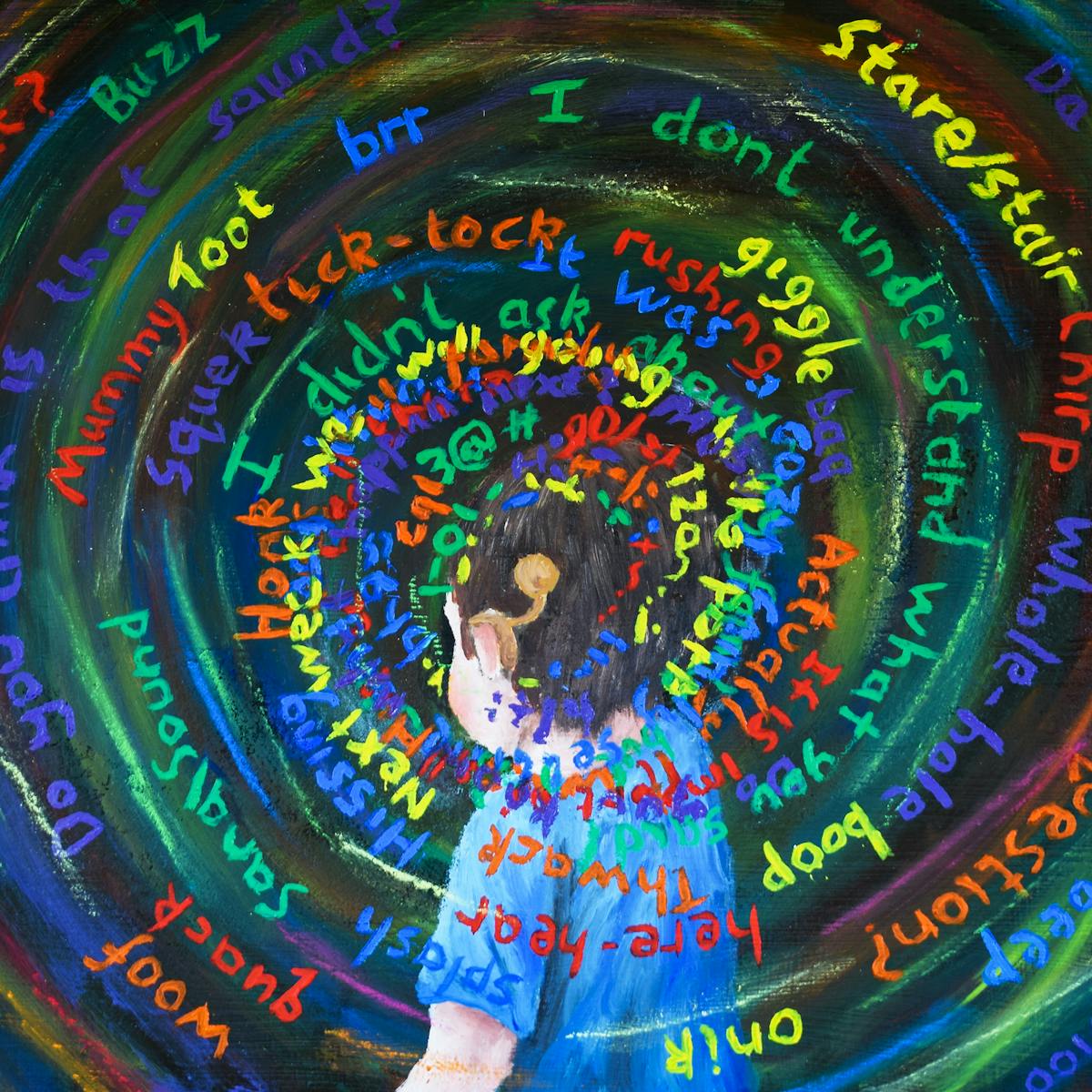

A cochlear implant amplifies all the noises in a room at the same volume. The brains of hearing people are able to focus on the voice or sound they want to listen to, and to block out extraneous noise, whereas implant users hear everything at once. Coffee grinders, traffic, car alarms, crying children, radios, televisions and scraping chairs all clamour for attention. The volume of a new implant is turned up gradually, over a series of months, so the wearer can get used to the new sounds.

As my brother began to hear, he slowly started to speak. He wanted to be part of the hearing world and used sign language less and less.

British Sign Language (BSL) users are a linguistic minority group, understandably passionate about preserving their language, which means cochlear implants are a controversial issue in the Deaf community (some people choose to use Deaf with an upper-case ‘D’, which signals that they are part of Deaf culture and are involved with the Deaf community, using a shared sign language).

At the Second International Congress on Education of the Deaf in 1880, professionals wrongly believed that a child’s ability to sign would reduce their ability to speak and lip-read, so sign language was banned in deaf schools, and students were forced to sit on their fingers.

BSL was passed on in secret, under desks, in dorm rooms and in the playground until the 1970s, when there was a push for sign language to be reinstated in deaf schools. Linguists pointed out that BSL is not merely ‘mime’, but a complex framework of symbols and semiosis, evolving to incorporate new words over time, yet it was not recognised as an official language by the British government until 2003. In 2018, a deaf student and his family fought for the introduction of a BSL GCSE in UK secondary schools, which is currently being evaluated by the Department for Education.

"The delay in language acquisition means it is more difficult to understand that other people think different kinds of thoughts."

Caught between languages

My brother went to a school for the deaf that emphasised spoken language. He stopped using sign and today his speech is excellent, but I often think about the ways in which he occupies a space between languages. To be deaf is not just about being unable to hear. The delay in language acquisition means it is more difficult to understand that other people think different kinds of thoughts. Innuendos and idioms have different meanings in English and BSL, which causes a cultural gap that jokes and sarcasm often cannot cross.

The development of language shapes so much of our understanding, and when that is interrupted the world becomes an unpredictable place. To be a cochlear implant user is to exist closer to the hearing world, but it also creates a distance from the Deaf community. Through lack of use, my brother’s sign is not fluent, but the hearing world of whispering and shouting, of snide remarks and compliments mumbled with hands over mouths is not a place he inhabits easily.

A feeling of privilege

Now that I am older, I am able to consider some of the more complicated feelings that arise from growing up with a sibling with a hearing loss. I have developed a solid sense of independence, which stems from being a child who had to look after herself a little bit more. I have an almost violent impulse to protect. And there is the oily guilt that comes when I consider the ways in which I have been careless with myself: when I have not eaten enough, or got too drunk, or the terrible, thrilling tingle in my ears after being at a gig without wearing earplugs.

These feelings are difficult to confront, because, even though my brother’s needs played a part in shaping my life, I am always the hearing person in a hearing world and my brave and clever little brother is not. And yet the feelings are there.

Due to the workplace discrimination that is still very much prevalent, despite equality and diversity monitoring, or a supposed awareness of additional needs, it has been difficult for my brother to complete a university course or find a job.

After one particularly sharp rejection, he turned to me and said, “It could have been you.” His words burrowed their heads deep into my stomach. “I could have been born first, and you could have been the deaf one. It could have been you and not me.” I felt so sad for his loss and the injustice of it all. I felt scared, because he was right. It could have been me.

"Due to workplace discrimination it has been difficult for my brother to complete a university course or find a job."

Our difference twists in my stomach when I help my brother complete a written task, like a job application or a letter. He marvels at the speed of my typing and how quickly I can dash out a paragraph that sounds professional and sophisticated. At first, I took my brother’s language deprivation and my proficiency in it as a sign of my sheer privilege, an ease that I wore too lightly, but I have come to understand that the two are connected, due to the weight on the importance of language in our home.

My subtitled childhood

My childhood was subtitled. We had lists of words spelled phonetically across our fridge. I watched ‘Annie’ and ‘Oliver!’ over and over, white letters spelling out the sound of “ORPHANS CRYING” and “NANCY SCREAMING”.

I learned the power of written language through ‘Coronation Street’ and ‘EastEnders’. Swearing and fighting were so much more violent when they were typed across our TV screen. Moments of intimacy made us squirm. My mother and I grew so used to the subtitles that we both claimed not to see them, but now I wonder whether my life as a writer was influenced by those early years where everything was written out before me.

Language is not easy for my brother, and yet it is my most effective tool. There was such an emphasis on different ways to communicate in our home that it must have informed my love of words and my decision to become a writer. I am most interested in literature that is concerned with the body, and my own writing is very sensory; packed with smells and tastes. I spend my days trying to find symbols for things that are difficult to say.

It is a contradiction, of course, to try and reach that which is beyond words through paper and ink, yet writing has become the best way I have of making sense of the world. I am interested in pushing the boundaries of form and language because it feels closer to the edge of what words can do. It is messy, unpredictable and honest, just like our bodies in all of their shifting forms.

About the contributors

Jessica Andrews

Jessica Andrews writes fiction. She has been published by the Guardian, Stylist, the Independent and ELLE magazine. Her debut novel, ‘Saltwater’, explores mother-daughter relationships, place, social class and the body. She teaches literature and creative-writing classes and co-runs the literary magazine the Grapevine, which aims to give a platform to under-represented writers.

Ruaridh Lever-Hogg

Ruaridh is an artist born and raised in the Scottish Highlands. He was a participant in the BBC's 'Big Painting Challenge' in 2017, overcoming the barriers that exist in communication between Deaf and hearing people. He has also run workshops to teach art to Deaf communities and Deaf organisations. His recent work involves using tartan fabric as his canvas, blending his subjects into the background of the tartan and revealing their individuality.