Delving in the Wellcome archives led Wendy Moore to the story of a flamboyant doctor whose famous fans included Dickens. But his experiments with hypnosis eventually met with establishment disapproval.

We think of libraries as places of quiet solitude where information is reassuringly organised, ordered and catalogued. Yet for me one of the best things about libraries is serendipity. It’s that unexpected jewel of information that changes everything, that missing jigsaw piece that solves a puzzle or – in my case – the chance discovery that led to my next book.

That serendipitous moment came on a cold January day in 2012 when I arrived at the Wellcome Library to do some research for a column I then wrote in the British Medical Journal. Since it was the bicentenary of Dickens’s birth, I had decided to write about the doctors in Dickens’s novels. I duly read about Sir Tumley Snuffim, Dr Kutankumagen, Mr Slasher and the various bumbling surgeons and grasping physicians with whom Dickens peppered his works. But it was a doctor who never appeared in a Dickens book, a doctor who became the author’s medical advisor and one of his closest friends, who transfixed me.

Charles Dickens on a lecture tour. Illustrated London News, 1870.

I chanced upon John Elliotson in a short book, 'Dickens’s Doctors' by David Waldron Smithers (1979), on the Library shelves. And as I read about this complex man, who was born into the Georgian era but became one of Victorian society’s most intriguing personalities, I recognised those unmistakeable symptoms – sweaty palms, thumping heartbeat and fluttering in the stomach – which are the surefire signs of a possible new book.

Title page of pamphlet published by E Hancock, 1842.

A quick check in the catalogue revealed there was no biography of Elliotson, but there were numerous works on the topic of mesmerism, the clinical technique devised by German doctor Franz Mesmer in the 18th century, which Elliotson specialised in. A search in the archives uncovered a treasure trove of curiously titled publications by and about Elliotson.

What on earth was The Zoist, which he edited for 13 years? What induced him to publish a pamphlet entitled ‘False accusation in the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society against a poor man because he suffered no pain while his leg was amputated in the mesmeric coma’? And why had he inspired a pamphlet with the even more intriguing title ‘A full discovery of the strange practices of Dr Elliotson on the bodies of his female patients’? I was hooked.

I discovered that Elliotson was the son of a prosperous chemist and determined in his early teens to become a physician. He gained not one but two medical degrees – from Edinburgh and Cambridge – trained at Guy’s and St Thomas’s hospitals, and established himself as one of the capital’s most respected practitioners. By 1837 Elliotson was Professor of Medicine at University College London (UCL) and a physician at University College Hospital (UCH), with a grand house and consulting rooms in the West End. And then he risked it all – by embracing a controversial new idea: mesmerism.

John Elliotson. Lithograph after J Ramsay.

Elliotson was no stranger to novelty or controversy. As an up-and-coming doctor he had discarded the traditional physician’s breeches for newly fashionable trousers and sported whiskers according to the latest trend.

This 19th-century hipster was an early adopter of medical innovations too – especially when they emanated from the Continent. He championed the stethoscope, dabbled with acupuncture and became one of Britain’s foremost advocates of phrenology. So when a French disciple of mesmerism, Baron Jules Du Potet de Sennevoy, arrived in London in June 1837 to promote his doctrine, Elliotson was first in line.

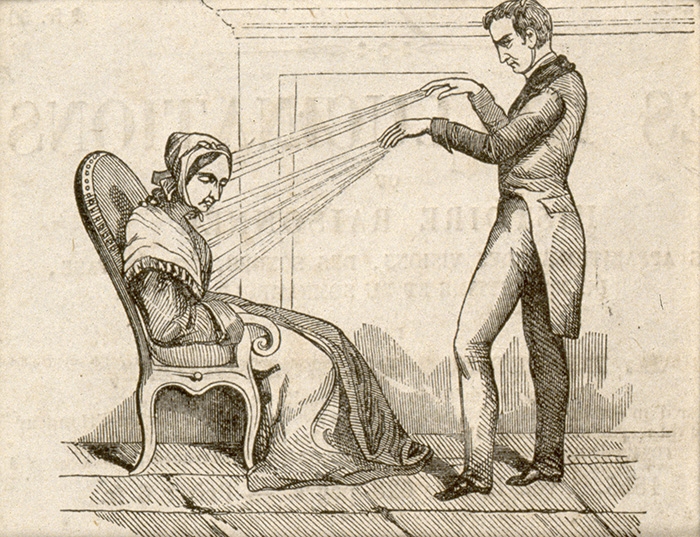

A mesmerist using animal magnetism on a seated female patient. Wood engraving, c. 1845 [French newspaper].

Mesmerism – effectively hypnotism – had been named after German physician Franz Anton Mesmer, who discovered in the late 18th century that he could induce a kind of sleep in his patients through repetitive hand motions and vocal suggestions. In this state, people slavishly followed his commands, lost their inhibitions and became insensitive to pain. Mesmerism garnered supporters throughout Europe but had failed to find a following in Britain – until Elliotson took an interest.

Elliotson invited Du Potet to try his technique on some patients at UCH and, impressed by the results, he adopted the method himself. Over the next 18 months Elliotson mesmerised dozens of patients at UCH and invited friends, colleagues and journalists to witness his experiments.

One of his guests was the young Dickens, who made the short journey to UCH from his house in Doughty Street in central London with his artist friend George Cruikshank on 4 January 1838. Elliotson’s casebooks, in the UCL archives, record their visit. Dickens was so bewitched by what he saw that he learned the technique himself – later practising on his wife Catherine and others – and became a lifelong enthusiast for mesmerism. Through his friendship with Dickens, Elliotson became the medical darling of the Victorian literary world.

Elliotson went on to stage dramatic demonstrations of mesmerism in the lecture theatre of UCH, which drew large crowds and sparked sensational headlines. In particular, spectators were entranced by the Okey sisters, 17-year-old Elizabeth and 15-year-old Jane, who were admitted to UCH for epilepsy.

Their names were routinely misspelled O’Key, and writers ever since have assumed the girls were Irish. In fact, genealogical records show that they came from a working-class English family in nearby Somers Town. Under mesmerism these two demure young women were transformed into more outgoing characters who joked and flirted with their audiences as well as lifting heavy weights and withstanding electric shocks.

Ultimately, however, Elliotson’s love of novelty was his downfall. Not content with showing that mesmerism could improve certain conditions and banish pain, he was bent on witnessing bizarre phenomena reported from the Continent, where doctors claimed patients could forecast the future, diagnose other patients’ ailments and distinguish ‘mesmerised’ water and metal.

When the Lancet demolished the latter theory in exhaustive tests on the Okeys, Elliotson’s reputation was severely tarnished. But he sealed his own fate by taking Elizabeth Okey to a ward, where she predicted two patients would shortly die. UCL promptly banned mesmerism and he had no option but to resign.

His reputation in tatters, Elliotson stayed faithful to mesmerism. He staged demonstrations in his own home, which were gleefully described in the anonymous pamphlet ‘A Full Discovery’. He founded the London Mesmeric Infirmary to offer mesmerism to poor patients; its sixth annual report survives in the Wellcome Library archives. And he launched his own journal, The Zoist, which ran to 13 volumes, to publicise mesmeric treatment and operations painlessly performed under mesmerism more than four years before chemical anaesthesia.

Chasing Elliotson took me on a three-year detective trail through the archives of UCL, the Royal Society of Medicine, Dr Williams’s Library and beyond. But it all sprang from a moment of serendipity in Euston Road.