In the second essay in this series Jaipreet Virdi describes the worsening of her pain, and how, in history, doctors saw experiences like hers as a punishment for women who chose to have careers before babies. A young wife’s duty was simply to reproduce.

The pain that punished feminists

Words by Jaipreet Virdiartwork by Anne Howesonaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

It was my birthday when my husband took me to hospital.

My abdomen was bloated, and I had been generally uncomfortable the entire day, but we had plans for a sushi date that I didn’t want to miss. As on many other days, I dismissed the persistent throbbing pain in the lower-left quadrant of my abdomen, waving it away as a muscle cramp, leftover period pain, or intestinal discomfort from a poor diet. I got used to the sound of the pill bottles rattling in my bag and seeing them strewn across my desk.

I wasn’t the only one ignoring the pain. Doctor after doctor dismissed me, sending me home with a prescription. They repeatedly told me the “tests are normal”. After all, how could they take my pain seriously when there was no tangible evidence of abnormality?

Even as the pain became excruciating, my condition was assessed as non-critical.

When menstruation works backwards

The endometrium is the lining of the uterus that, every month, thickens itself in preparation for pregnancy or sheds and induces menstruation. It has two mucosal layers: an unchanging basal layer that anchors the endometrium to the uterus, and a functional layer that changes monthly accordingly to the menstrual cycle.

As early as 1860, surgeons reported finding aberrant pieces of endometrium outside the uterus in the rectovaginal area, the ovaries, and even on the bowels. None, however, could adequately explain how or why this happened: but by 1898, William Wood Russell of Johns Hopkins University outlined a detailed description of endometriotic cysts, providing further confirmation of the presence of endometrial tissues outside the uterus.

More: Ten pieces of (terrible) historical advice on how to handle your period.

In 1921, at the Albany Hospital in upstate New York, gynaecologist John A Sampson observed several patients with what he termed ‘chocolate cysts’: non-cancerous cysts filled with old menstrual blood, a thick brown fluid. While performing pelvic surgery on patients who were menstruating, Sampson discovered that the cysts perforated, releasing blood and tissue lining across the pelvis. He also observed that the cystic lining was similar to the menstrual lining, even corresponding to the patient’s menstrual cycle and pelvic inflammation.

Sampson investigated this condition on 293 patients. Since endometrial tissue was often found near the end of the fallopian tubes and against the ovaries, he theorised that menstrual effluent regurgitated upwards towards the fallopian tubes and into the pelvis. Once there, the regurgitated tissue adhered to the pelvic organs and replicated itself to create adhesions – scar tissue that stuck organs together.

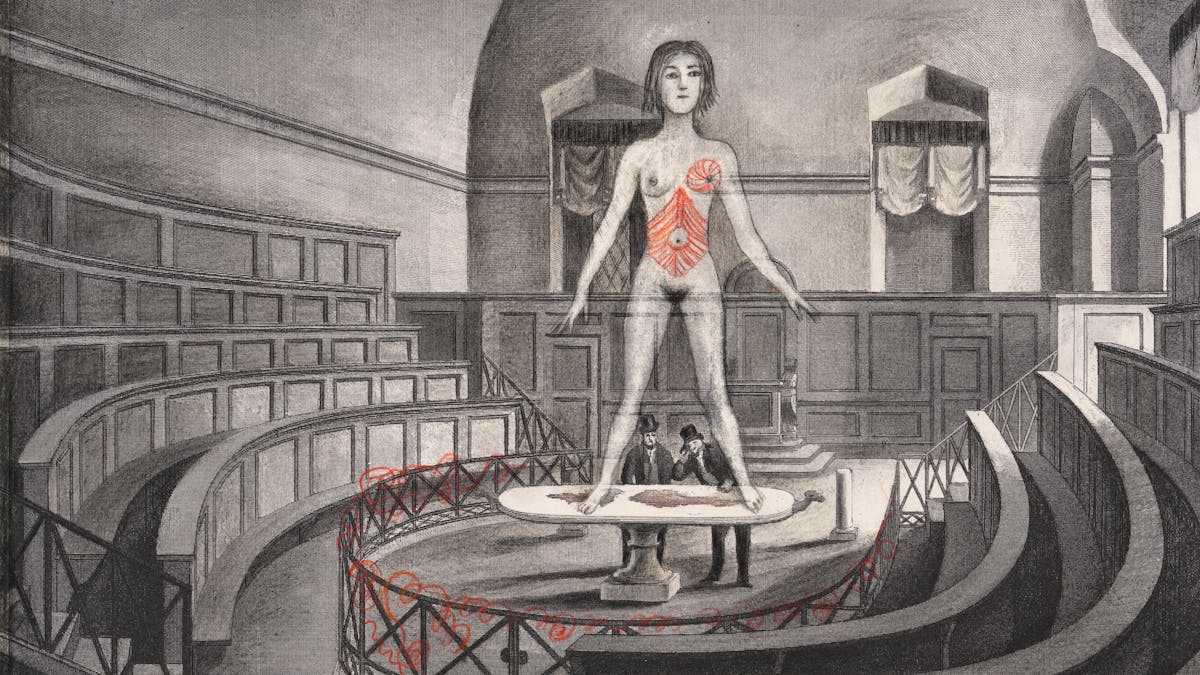

It was only in the 1920s that people began to rigorously investigate endometriosis. The illustrations above were created in 1925 to educate medics about what this condition looked like internally.

This was his theory of retrograde menstruation and helped to explain the presence of endometrium outside of the uterus, a condition he termed ‘endometriosis’.

By 1927, the gynaecologists became familiar with Sampson’s description of the causes of the disease and its visual signs: multiple adhesions, cysts, dark lesions in the pelvis, inflammation, and perhaps above all, the most concerning consequence – sterility.

A woman’s duty to reproduce

A year after Sampson’s definition of endometriosis, another gynaecologist decided to see if he could verify the theory.

Since 1903 Joe Vincent Meigs had been collecting tissue samples from patients at Vincent Memorial Hospital in Boston and in 1921, he observed the samples contained endometrium, as Sampson outlined. He also examined chocolate cysts, as Sampson did, but observed something peculiar about them: they were often seen in affluent and ambitious women who put off childbearing.

In Meigs’ view, the consequence of these women’s actions was the social malaise of endometriosis. As he observed, endometrial cysts tended to atrophy or disappear during pregnancy and breastfeeding; early and frequent childbearing was a natural physiological process for women that was meant to keep the disease at bay.

Endometriosis was increasingly referred to as the ‘career-woman’s disease’.

Those who delayed their natural duties, then, became the dominant risk group for endometriosis, a disease that Meigs claimed was led by women’s decisions to plan their lives based on financial security, instead of following biological laws. As Lisa Michelle Sanmiguel outlines in her 2000 PhD dissertation, Meigs refined his theory during the Great Depression when “rising unemployment, increased use of contraception, and expanding urbanization were contributing to record low birth rates”, leading to greater anxieties about race suicide. After all, endometriosis was a disease that appeared more in wealthier patients than in “less well-to-do patients” who produced multiple children.

People feared that autonomous, independent, emancipated feminists would both undermine the fabric of society and cause themselves illness.

In 1948, Meigs gave a widely publicised lecture at the American College of Surgeons to introduce endometriosis to the general public. He also advised physicians to withhold contraception from their wealthy patients, for the lifestyle of the modern woman, Meigs insisted, was an illogical one: “What is more pathetic than the girl who married and for economic reasons can’t have a baby, who later goes to her doctor with a sterility problem that cannot be solved?” A woman’s reproductive capacity became more privileged than her pain.

Meigs’ eugenicist concerns not only created a crisis about declining birth rates, but blamed working women for an array of social problems. Endometriosis became tied to a woman’s reproductive capacity and was increasingly referred to as the ‘career-woman’s disease’. By the 1970s these messages heightened in response to second-wave feminism, the development of the contraceptive pill, and Roe v. Wade, the 1973 case that revolutionised abortion law in the US.

In the meantime, my body struggled to compose itself. The disease took its roots, growing in mass, with tendrils creeping towards my other organs and wrapping themselves around them. Little did I know that in a few months’ time, the pain would worsen such that I would no longer be able to walk without becoming temporarily paralysed by the stabs of agony. My body began to hunch over, constantly trying to assume a foetal position to protect itself, to hold on until relief could arrive.

About the contributors

Jaipreet Virdi

Dr Jaipreet Virdi is a historian of medicine and disability based at the University of Delaware. Her first book, ‘Hearing Happiness: Deafness Cures in History’ is available where books are sold. She is currently working on her next book, ‘An Invisible Epidemic: The History of Endometriosis’.

Anne Howeson

Anne Howeson develops projects concerning place, time and communities. She is a Jerwood Drawing Prize winner with drawings in the collection of the Museum of London, the Guardian News and Media, St George’s Hospital and Imperial College London. She was shortlisted in 2014 for the Derwent Art Prize and the National Open Art Award, and in 2017 for the Ruskin Prize. She has twice been an invited artist with ING Discerning Eye. As a tutor at the Royal College of Art she promotes drawing in all its forms – through process, outcome and as a way of thinking.