Quacks is a medical comedy set in Victorian London that riffs off the hair-raising surgical tools and techniques of the 1840s. It’s silly and fun, but it’s also rooted in genuine research. How did its creators balance authenticity with humour? Writer James Wood, production designer Lucy Spink, and costume designer Richard Cooke welcome us into their world.

In pictures

Tom Basden being transformed into dentist and budding anaesthetist John Sutton.

Tom Basden and Mathew Baynton keep warm while rehearsing an ether scene.

Rory Kinnear works on his amputation skills as Robert Lessing.

Caroline (Lydia Leonard) and William (Mathew Baynton) dine with Dickens (Andrew Scott).

James Wood, writer

-

Where did the idea for Quacks come from?

I realised there was this amazing 10 to 15 year period in medicine in the middle of the Victorian era where lots of the medicine we now enjoy was pioneered and experimented. Then I read a few medical history books, particularly one about the medical history of London by a guy called Richard Barnett, who is now our consultant. It's a really entertaining book: extraordinary stories of doctors across the ages. I zoned in on this bit of Victorian medical history in the 1840s because that’s when anaesthesia was first pioneered. I learned about these incredible dentists who'd experiment on themselves. Lots of them became drug addicts, and there was this sort of rock and roll, raucous, lunatic element to these men.

How did you research the show?

Wellcome opened up their resources, this incredible library, and so I read their books, and they put me in touch with one of their writers. Their medical historians are very entertaining, funny people, so that’s great. And I’ve got a couple of friends - Nick Wilson Jones, a paediatric surgeon, and James Down who’s a consultant anaesthetist - who helped us with the medicine as well.

Is there anything you had to tweak in the script for accuracy’s sake?

I think the medicine is all accurate but sometimes there were issues with dates and timing. Richard Barnett read all our scripts and would then send what he called 'super pedantic emails' and sometimes we had to change bits. I think audiences can feel generally if something is authentic, but they don’t really care about absolute precision.

In pictures

An authentic Victorian street scene, complete with quack.

The operating theatre was purposely made into a dirty, bloody place.

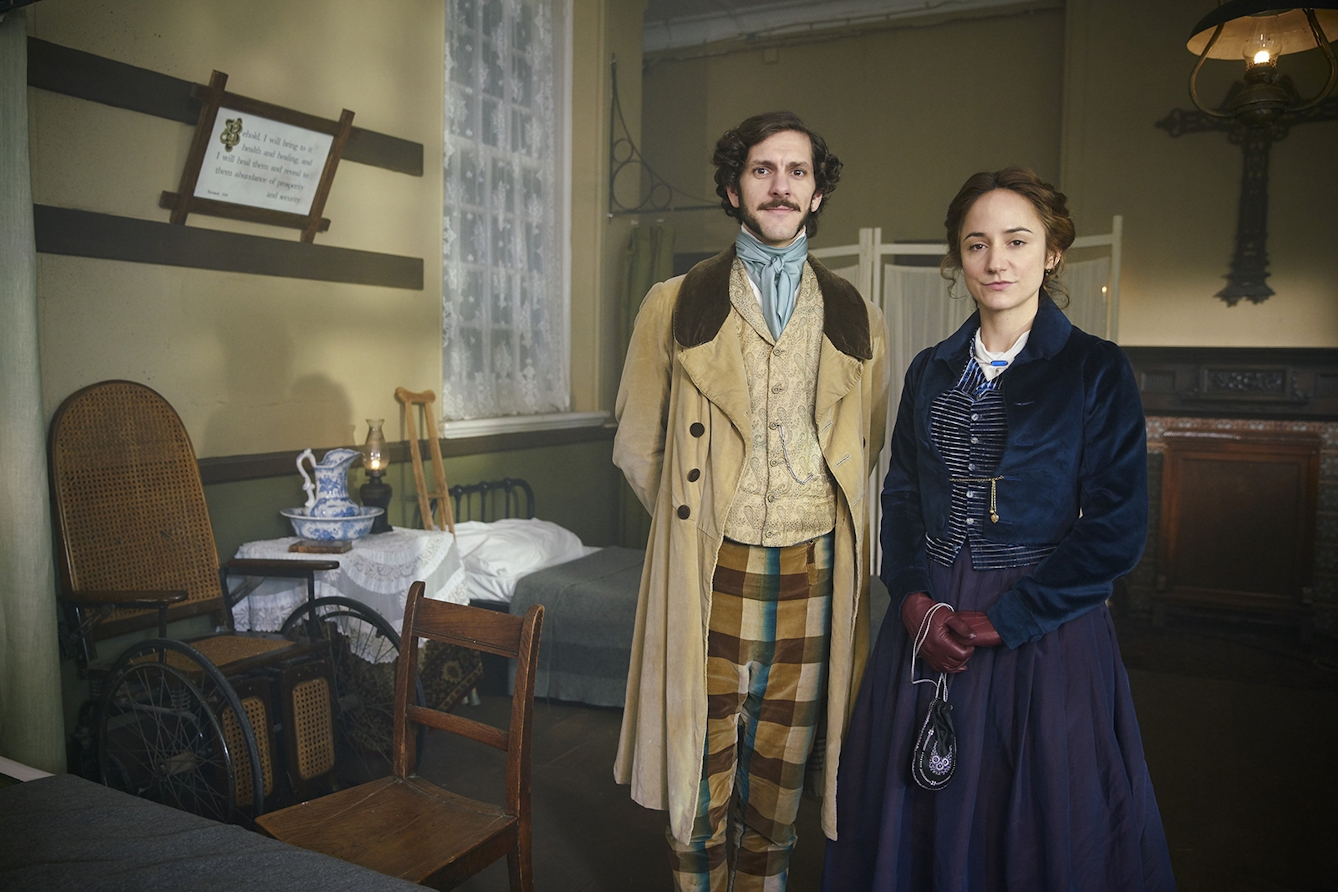

William and Caroline inside an 1840s style hospital.

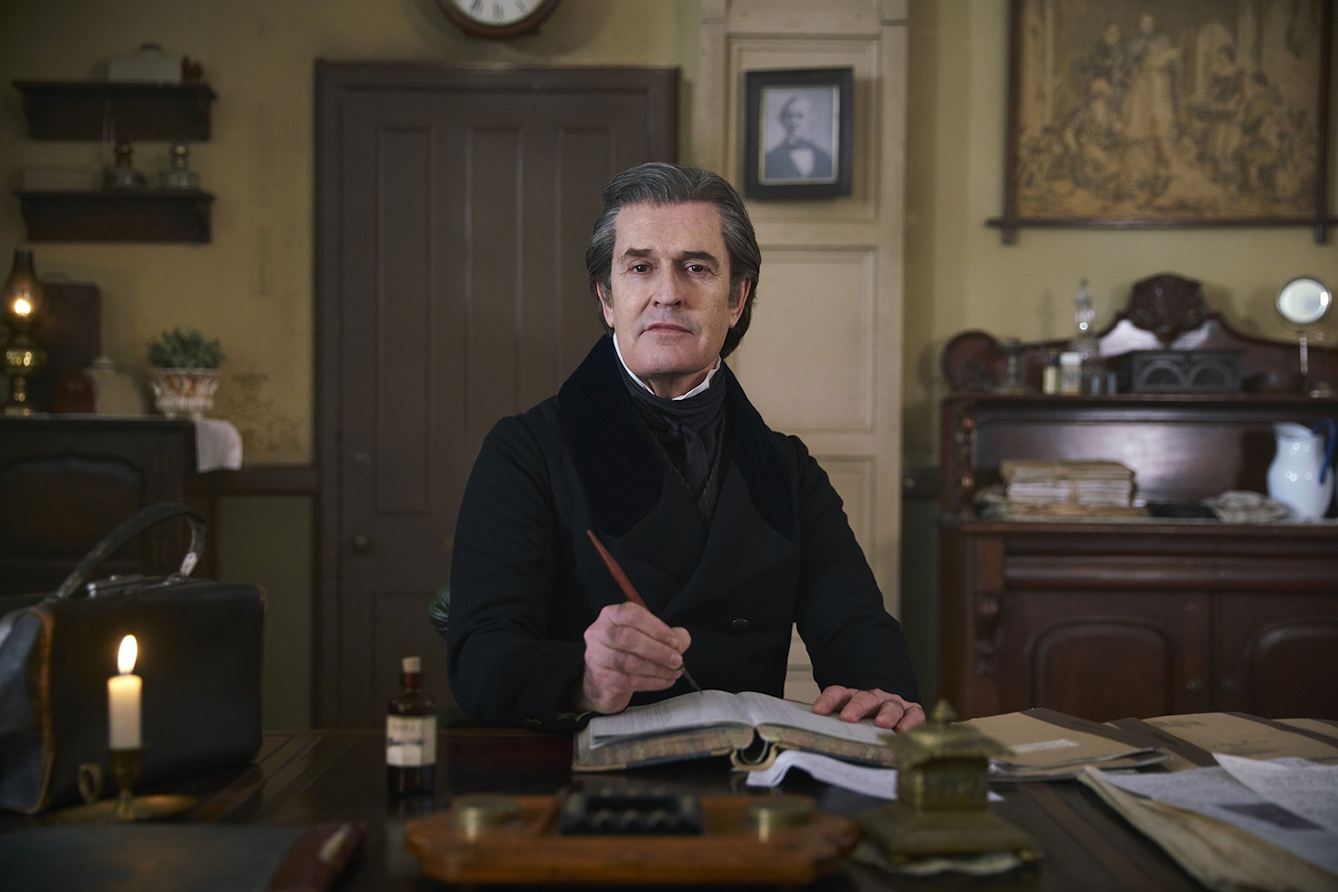

Dr Hendricks (Rupert Everett) in his study.

Robert, John and William in the pub.

Lucy Spink, production designer

-

Have you ever worked on a medical drama before?

I worked on Holby City years ago. It's funny to compare the difference, and obviously the huge advance in technology is the biggest change. There are similarities though. A ward with some beds, a surgery table in a theatre with the medical intelligentsia standing around, all hoping some new procedure will work. The settings and the drama is the same, even when the technologies are centuries apart.

How did you select the locations used in Quacks?

The location hunt generally began in areas around London that are known for their historic architectural integrity. The Historic Dockyard at Chatham has had many period recreations staged there. We were looking to create an authentic early Victorian street scene and there are little alleyways and corners with cobbled streets and old brick-work which provide a great starting point.

After that comes the research, and here there is really no limit: shop windows, street sellers, market stalls, signage, goods, produce, transport, etc. We added as much detail as possible to allow the director, Andy, to feel he had 360 degrees to shoot within. The period is just before the dawning of photography so any etchings, paintings, cartoons and written descriptions are invaluable, but better than all of the above is seeing the items for real.

To be so filthy and dirty in the medical areas was refreshing, and almost counter intuitive to how we think and live today. We added dirt and blood stains and filth to the operating theatre set, and all the tools. When dressing the hospital it really dated it by adding heavy woollen table-cloths and knitted doilies. It all helped to create a place very different to our hospitals today.

Are any of the medical tools replicas based on real things?

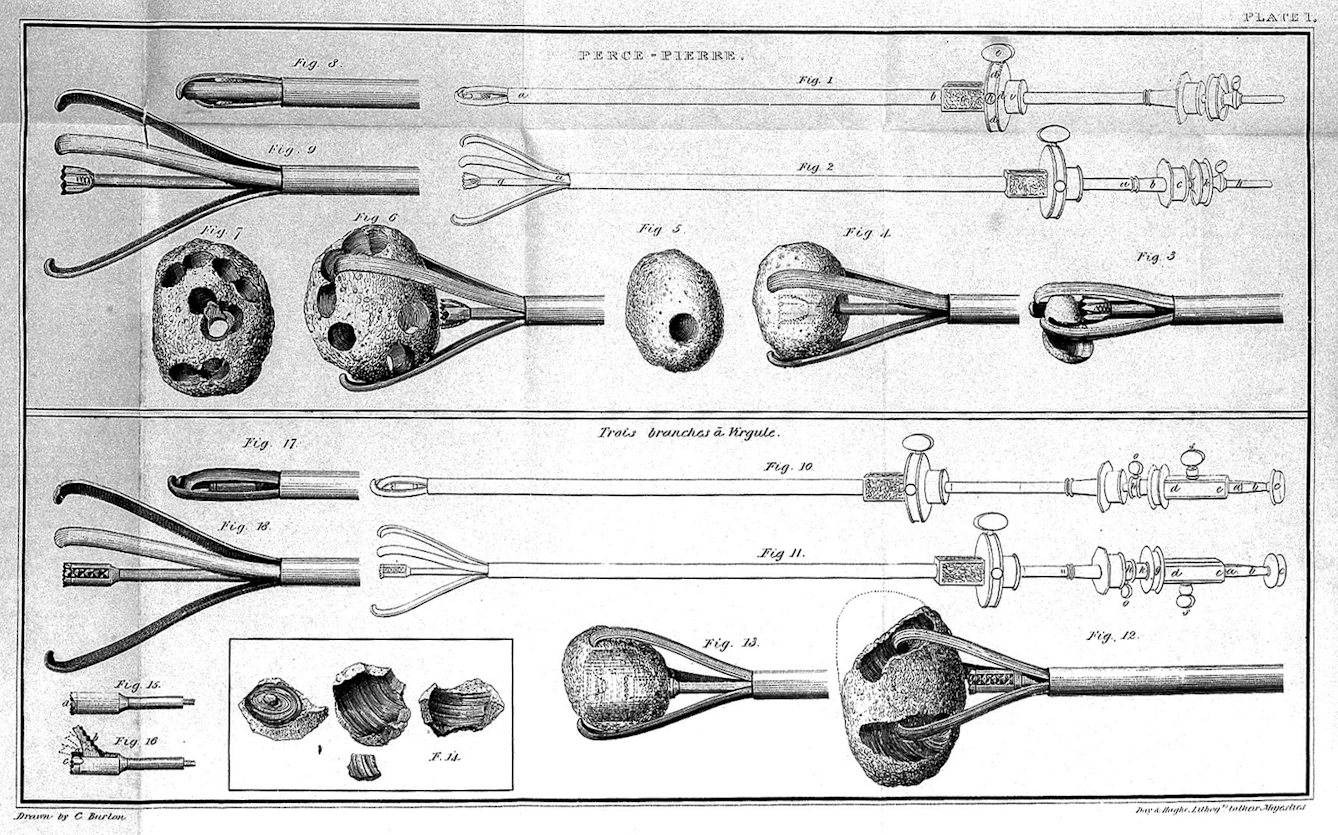

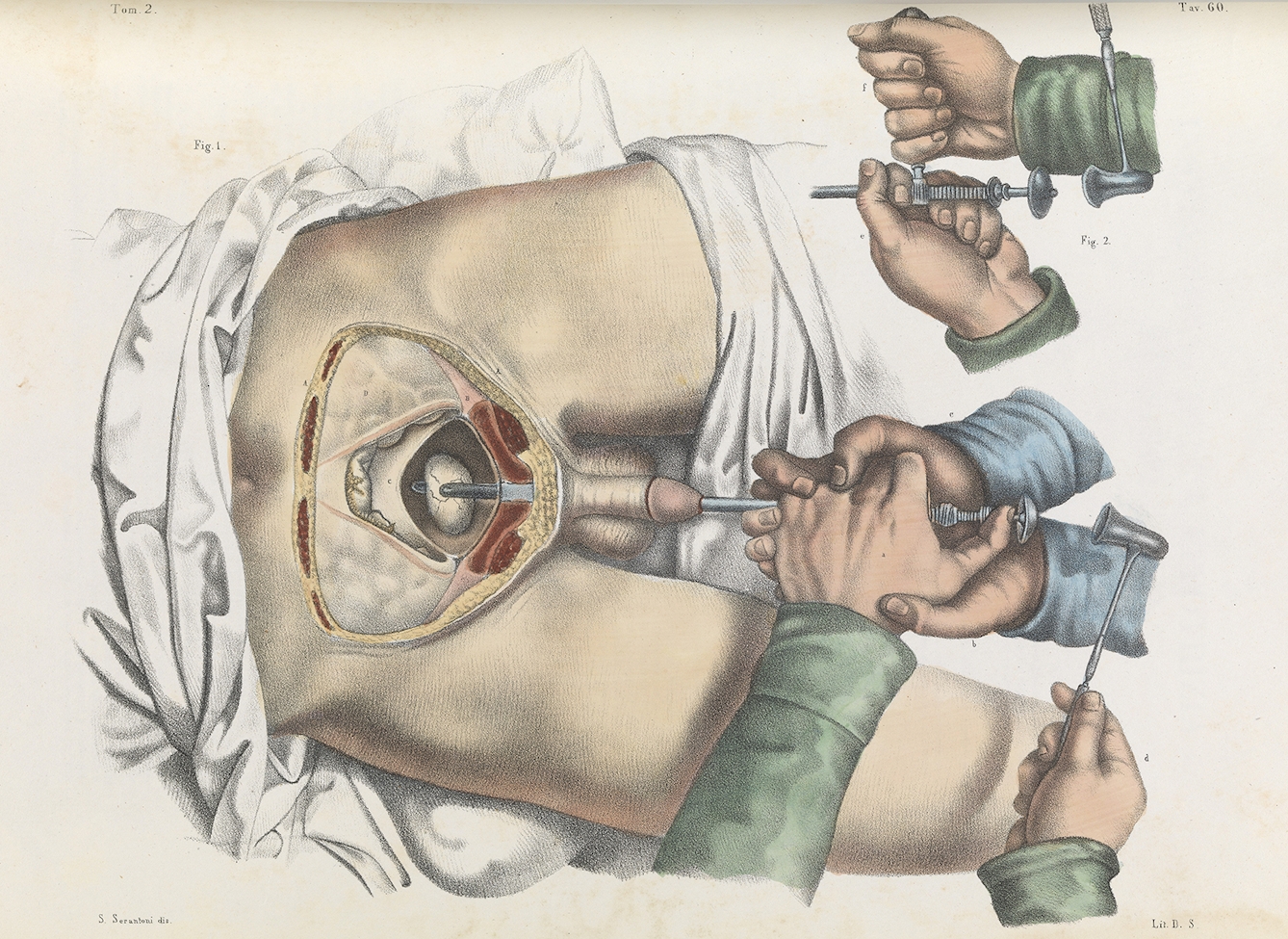

Medical procedures occur throughout, and it was paramount for us to make them as realistic and as truthful as possible, especially as the historic reality provides all the gory and shocking scenarios you would ever need! We consulted Wellcome often, whose wealth of source reference material, especially historical diagrams and medical illustrations, became our bible.

One of our heroes - dentist and budding anaesthetist John Sutton - is constantly trying to perfect an ether delivery device. Myself, and my very brilliant Art Director Anna Sheldrake, visited the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. They had a great collection of the very early chloroform and ether dispensers.

And when we had to create a barbaric and yet credible lithotrity device we trawled Wellcome’s images and resources to find all the period depictions. Anything we could find that provided a good representation of the real thing gave us a great starting point. If we then decided to exaggerate parts a little it was from an informed position. The lithotrity device was certainly one that brought tears to my eyes, and all the men on the crew!

In pictures

"One of our heroes - dentist and budding anaesthetist John Sutton - is constantly trying to perfect an ether delivery device."

One of John's inventions for administering anaesthetics.

"When we had to create a barbaric and yet credible lithotrity device we trawled Wellcome’s images and resources to find all the period depictions."

This illustration of lithority in action from 1827 provided eye-watering inspiration for the scenes where William has to have a bladder stone removed.

More eye-watering inspiration from the Wellcome Library, this time a full colour illustration from 1841.

Are you anticipating any audience feedback in terms of the historical accuracy?

I hope we created a believable enough world that, when we decided to take dramatic license and exaggerate here and there for humorous effect, the audience will recognise that and enjoy the decision with a wry smile as it is intended. The comedy comes from the characters. Their ridiculous behaviour within a serious and credible setting heightens the jeopardy. As soon as the sets and props become ridiculous or unlikely I think can you lose interest and the audience might start to care less.

If I receive any feedback on certain medical props and devices I will take that as a good thing! I hope it means that an informed and educated audience are so engaged that, rather than writing us off as a comedy with low expectations, they care enough to comment. Some of these procedures and equipment were so niche, but also new and inventive, that there must be variables in how it all evolved.

In pictures

Robert's bloody smock was designed to be a badge of honour, and to reflect his great medical prowess.

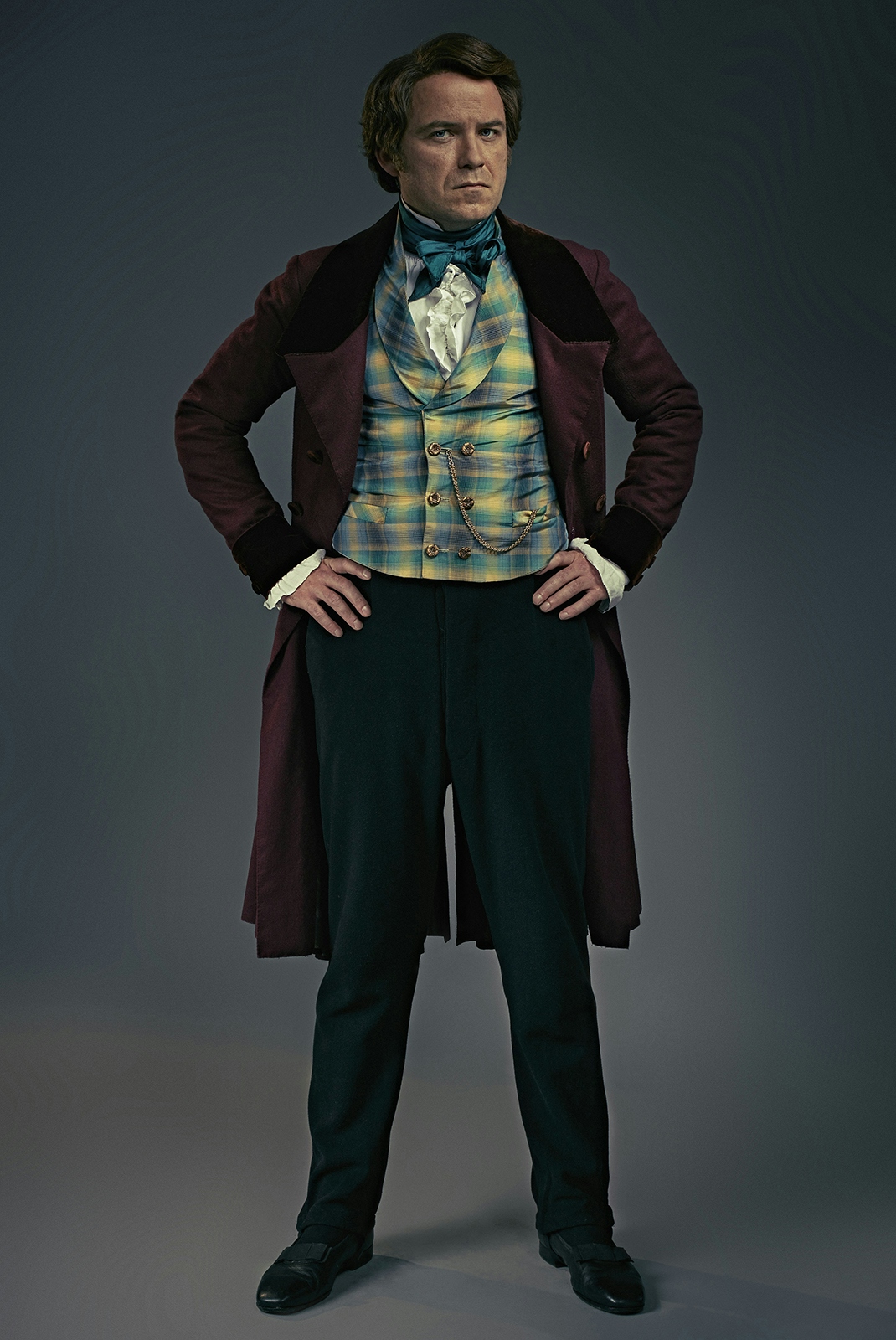

Robert dresses in vibrant jewel-like colours.

In a few scenes Caroline wears purple, the colour of emancipation.

At one point Caroline has to dress as man in order to gain access to a lecture at the Society of Apothecaries.

John the penniless dentist and ether experimenter wears suitably scruffy attire.

William, a well-dressed 'alienist', holding his phrenology head.

Richard Cooke, costume designer

-

How did you go about getting the clothes right?

You have to immerse yourself in the period, not only in terms of the clothes, but also what was happening in society, technology and the arts, as they all influenced what people wore. At initial 'look meetings' with the director, producers and writer, we discussed how we wanted Quacks to look real, vibrant and unique.

Looking at real garments of the period (the V&A have a great archive) is a good starting point in understanding the cut of clothes, how they're made, the fabrics and colours. Our perception of early Victorian London is influenced largely by paintings and previous productions and films we've seen. However, it was interesting to find that it was a surprisingly colourful period for fabrics and not everything was black or brown. This was perfect for our production.

Robert is a 'peacock' so I used vibrant jewel-like colours to reflect this, with complementary patterned silks for his waistcoats, to create an air of opulence and swagger. John is a penniless dentist who cares little for his appearance, and whose clothes are faded, well-loved, and show wear and tear.

It's very important that clothes reflect social status as it gives depth to a character and the show. I worked very closely with Sands Film, who have a fantastic collection of clothes which helped inspire me and the look we created.

The bloody smock worn by Rory Kinnear’s character Robert is especially gory…

The earliest photos I found of an operation were from around 1850 and, although it was later than our date, it gave me enough clues to inform what our surgeons should wear. Operating gowns weren't worn in the 1840s but we wanted something that would be seen as a badge of honour and reflect Robert's great medical prowess. We had great fun recreating the blood spurts!

What was it like dressing Lydia Leonard’s character Caroline?

Caroline is very forward thinking, and an early 'suffragette' in many ways. I didn't want her to be overwhelmed by petticoats and crinolines, which was the norm for the time. Her costumes are freer than the other women in the show, simpler and more practical, but still feminine and in some cases alluring.

Dressing women as men is always a challenge for obvious reasons! The fact that Caroline had to dress as a man to gain access to a lecture clearly shows society's attitude to women of the time. There are some instances in late Victorian England of women who lived and dressed as men. While this didn't directly inform Caroline's look, it was interesting to read about.

We wanted our world to be populated by real people and facts, but we were making a piece of entertainment not a documentary. In a few scenes Caroline wears purple, which didn't exist until the 1850s, but we chose that colour as it was later used as a colour of emancipation; it's about what adds value and helps the story.

About the contributors

Helen Babbs

Helen is a Digital Editor for Wellcome Collection.