If you have a visual impairment and would like to watch a film or TV series, you can turn on audio description, which relays everything that is not dialogue to you. But very few shows include it. Alex Lee explains how AD’s promising start has become mired in legal issues and red tape in the UK.

The joys and failures of audio description

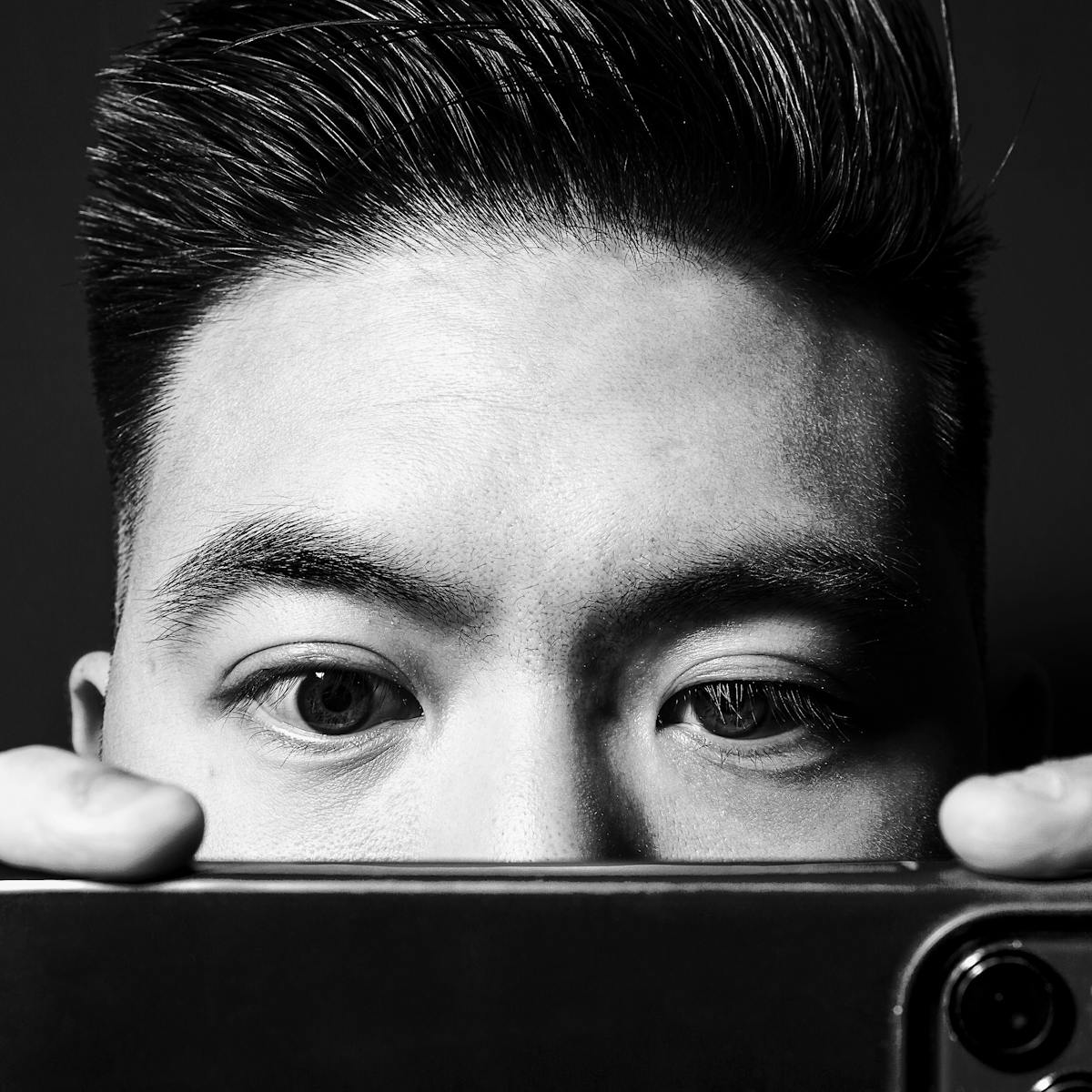

Words by Alex Leephotography by Ian Treherneaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

In a neutral voice, a deep-voiced man says, “in time lapse, cars race across a curving bridge as dusk turns to night. A waterfall with a rainbow. A neon sign. Twin peaks. Two elephants. A scone on a plate while tea pours.. Men play cricket. Long-haired sheep. Fishermen with nets. Big Ben. Westminster Palace. Lava spurts. Golden sunlight bathes San Francisco as fog rolls over a hill toward it. Cut to black.”

If you have a visual impairment, the detailed description above is what you’ll hear when you turn on the Netflix series ‘Sense8’ and play the fast-paced opening credits. It’s just one of several shows that have been audio-described by a trained narrator. Descriptions of what’s happening on a TV screen in between dialogue have only been around for a few years, but it’s made a permanent impact on visual media for those who cannot see.

In 1981 a visually impaired American woman named Margaret Pfanstiehl received a call from Wayne White, the house manager of the Arena Stage Theatre in Washington D C. White had a $10,000 grant from the Public Welfare Association to help make the theatre’s productions more accessible for people with disabilities. He’d installed sound amplifiers to assist those with hearing loss. But now he wanted to make going to the theatre more enjoyable for blind and visually impaired people, too.

Margaret Pfanstiehl (then Margaret Rockwell) was the founder of Metropolitan Washington Ear, a non-profit organisation that made printed news readily accessible to visually impaired people by reading it over the radio. Pfanstiehl had just finished an audio-description project named ‘Washington’s Neighbourhoods: A History of Change’, which was a series of ten tapes in which a narrator described the geography and history of the state for visually impaired people. Making a play accessible was the obvious next step.

She recruited Cody Pfanstiehl, the voice of the Washington Metro (and who she ended up marrying), to help her in the goal of making accessible theatre a reality. It would be called audio narration.

A verbal camera lens

Pfanstiehl decided that audio narration should consist of somebody describing the setting of scenes, action, costumes and the body language of the characters in the pauses between dialogue so that visually impaired people could follow what was happening on the stage. “You work only with the empty spaces that have been left,” Pfanstiehl said in an interview with the Washington Post in 1985. “It is a pictorial expression and you must be the verbal camera lens so that the visually impaired person can ‘see’ what everyone else sees.”

The narration was transmitted to people in the audience via infrared headsets. The first play to use the technology was a production of Bernard Shaw’s ‘Major Barbara’. Over the years, the Pfanstiehls would train volunteers how to describe plays for the blind, bringing audio description to theatres across the country. The following year, audio description was developed for a TV show called ‘American Playhouse’. The show was described live over the Washington Ear radio service, synchronised with the action on-screen.

“A few years ago, I began documenting every trip I took to the cinema, noting down exactly when the audio description worked on a film and when it didn’t. It’s only ever worked 10 per cent of the time.”

The delivery of the audio description was just as important as the technology. The right voice for the right film; the right verb or the right adjective; timing – it all helps to paint a vivid picture of what you can’t physically see. As Pfanstiehl said in a Reuters interview, “I remember once going with a novice describer to a performance of ‘The Caine Mutiny’. She said (into the earphone), `He’s leading the witness on.’ I said, `You don’t do that. Blind people can hear, the problem is that they can’t see.’”

Audio description only arrived in the UK in the late 1980s, when the Royal National Institute for Blind People (RNIB) set up an audio-description advisory group. After new infrared systems had been installed and volunteers were trained, the Theatre Royal Windsor put on the first audio-described production in the UK in 1988.

The right voice for the right film; the right verb or the right adjective; timing – it all helps to paint a vivid picture of what you can’t physically see.

Anne Hornsby, a pioneer of audio description in the UK, remembers her first production vividly. She was working as the head of front of house at the Octagon Theatre in Bolton in 1988 when a frequent theatregoer who had recently lost her sight asked if she had heard of something called audio description.

“She was considering stopping going, really, because it wasn’t a satisfying experience,” she says. “So I talked to our chief technician about how we could get the signal of the describer’s voice to the listener, and I asked her the sorts of things she needed to know.”

After a while, Hornsby says, “Different people from different theatres came and said, We’d like you to do this in Liverpool, we’d like you to do this in Manchester. We’d like you to do this in Oldham, we’d like you to do this in our gallery, and it all spread from there.”

She remembers that audio description was originally transmitted using a radio system, but in the mid-1990s it moved over to Sennheiser infrared. In recent years, it’s started using wifi, broadcast to users’ phones, allowing them to listen to the description using their own headphones.

“Technology has advanced, but cinemas are still delivering pre-recorded audio-described tracks through the same infrared headphones as in theatres. Archaic technology and a lack of regulation is holding audio description back from excelling.”

A disappointing lack of development

Audio description has been slowly rolled out to TV and then films since the 1980s. Since 1996, UK broadcasters have been required by law to include audio description in at least 10 per cent of their output. In 2017, Ofcom drew up a recommendation to make this a legal requirement for streaming services and video-on-demand platforms operating in the UK; the legislation is still pending. There is no legal requirement, besides the 2010 Equality Act, for cinemas to provide audio description.

Technology has advanced, but cinemas are still delivering pre-recorded audio-described tracks through the same infrared headphones as in theatres. Audio description has helped me enjoy the cinema again, but archaic technology and a lack of regulation is holding it back from excelling.

Smartphone transmission hasn’t been adopted widely in the UK. In 2017, the RNIB launched a trial screening of ‘Beauty and the Beast’ for visually impaired participants at the Odeon Cinema in Haymarket, London, using an app called MovieReading. Despite positive feedback, the trial hasn’t been expanded further.

“It’s legal issues which have been holding it up,” says Tim Calvert, an access consultant at the Audio Description Association. “The copyrights, people having access to material, access to contracts. That’s what’s been creating the problem between the distributors and the producers. And that’s your problem – it’s jumping through all the red tape, and all of those hurdles.”

A few years ago, I began documenting every trip I took to the cinema, noting down exactly when the audio description worked on a film and when it didn’t. It’s only ever worked 10 per cent of the time. A pile of complimentary tickets, given as compensation for the inconvenience, has been growing ever since.

Calvert says that, unfortunately, I’m not alone. “It’s something that used to come up on an almost regular basis in the UK Cinema Association,” he explains. “Unless people actually start ringing up or sending letters or emailing and saying: ‘Well, you know it’s not inclusive for us, you need to get your act together,’ then they’re not going to change. It really does come down to that.”

It’s not a lack of technological innovation that is holding audio description back, but the same issue of advocacy on the part of blind people. Without the demand, without people actively complaining to their local cinema chain theatre, or broadcaster, we aren’t going to get the audio description we need.

About the contributors

Alex Lee

Alex is a tech and culture journalist. He is currently tinkering with gadgets and writing about them for the Independent. You may have previously seen his work in the Guardian, Wired and Logic magazine. When he’s not complaining about his struggles with accessibility, you’ll likely find him in a cinema somewhere, attempting to watch the latest science-fiction film.

Ian Treherne

Ian Treherne was born deaf. His degenerative eye condition, which by default naturally cropped the world around him, gave him a unique eye for capturing moments in time. Using photography as a tool, a form of compensation for his lack of sight, Ian is able to utilise the lens of the camera, rather than his own, to sensitively capture the beauty and distortion of the world around him, which he is unable to see. Ian Treherne is an ambassador for the charity Sense, has worked on large projects about the Paralympics with Channel 4 and has been mentored by photographer Rankin.