When Aparna Nair was diagnosed with epilepsy as a teenager, her mind revolted and her body became a battlefied. But history reveals that epilepsy has always existed in that troubling space between the mind and the body.

The epilepsy diagnosis

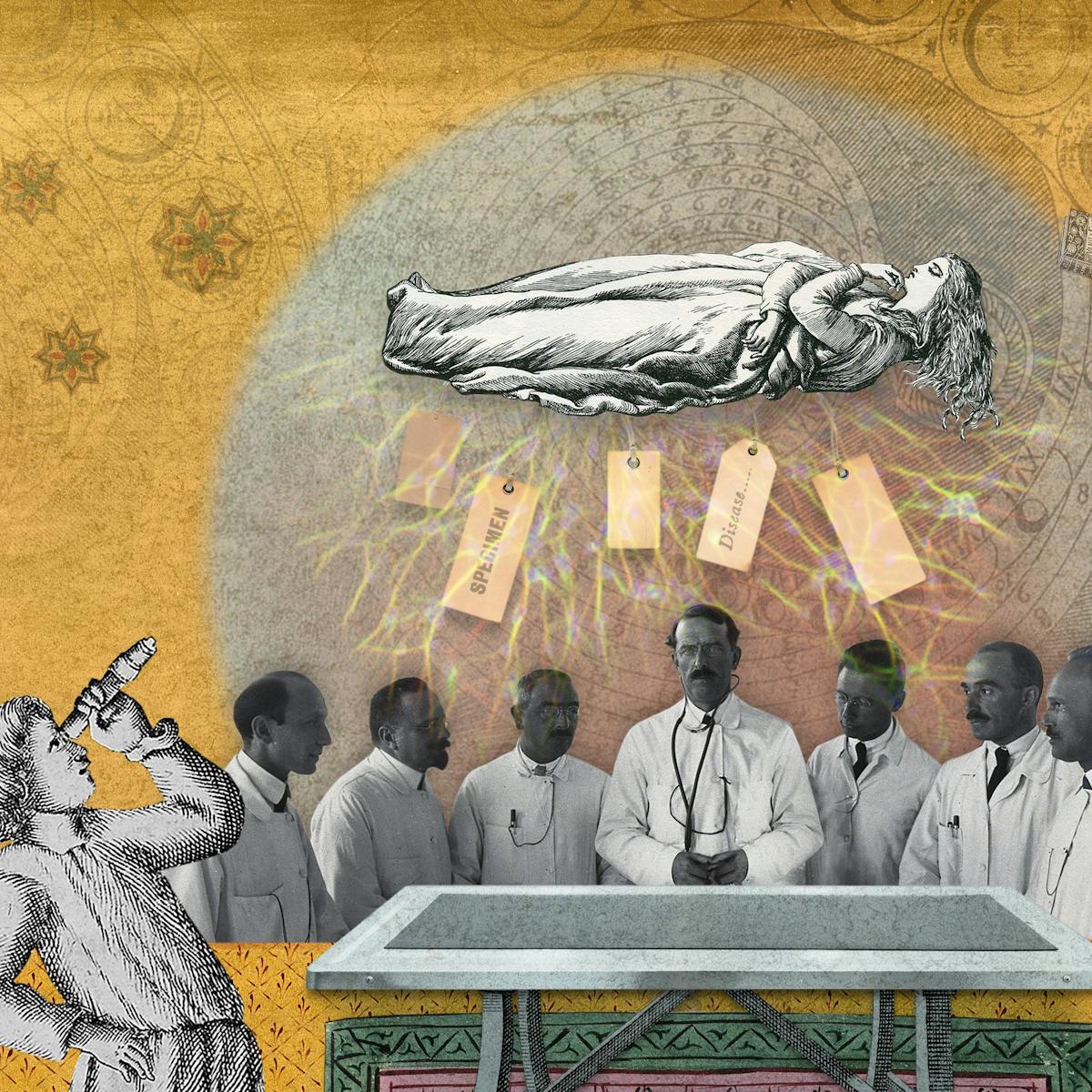

Words by Aparna Nairartwork by Tracy Satchwillaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

I was born into a financially comfortable doctor’s family in South India, so naturally we looked to the medical establishment for an explanation of my seizures. In the years after I had my first seizure at the age of 11, I spent a lot of time in and out of hospitals, waiting for doctors and test results.

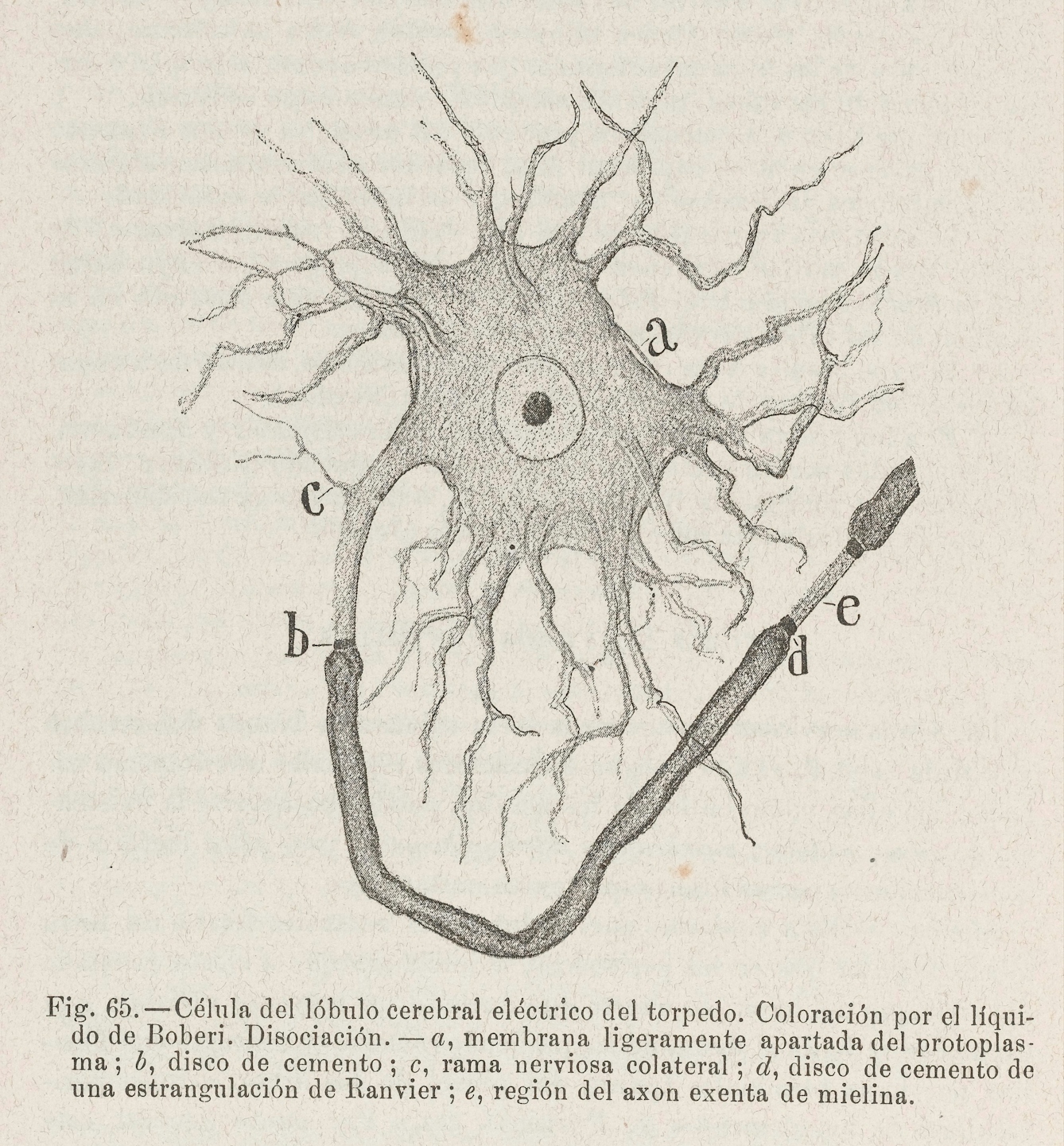

The barrage of invasive and uncomfortable tests eventually bore fruit and the doctors were able to establish that my seizures were due to epilepsy, originating in ‘foci’ of electrical activity in the brain.

Physically adjusting to epilepsy

My experience of chronic illness demystified modern medicine for me. I learned that doctors do not know everything. My medical records reflect how neurologists tussled with various categories of epilepsy to identify my particular illness. First I had “benign Rolandic epilepsy”, then “idiopathic epilepsy” and later I was diagnosed as having “juvenile myoclonic epilepsy”.

These labels meant little to me for much of my adolescence as I contended with the capricious and elusive entity that seemed to take control of my body whenever it pleased.

A chemist dispensing pills.

As doctors constantly fiddled with the levels of anti-convulsant drugs to keep the seizures in check, my body lurched from experiencing one set of side effects to another. My weight ballooned. I began to lose my balance and I found myself increasingly unsteady on my feet. My hair fell out in clumps. I struggled to concentrate for longer than a few minutes on anything.

Mentally adjusting to epilepsy

As my illness progressed, I lost months of school to post-seizure fogs as well as needing to heal from broken bones and concussions I sustained during seizures. Teachers told my parents to “keep her home until she gets better”, underscoring my sense of not belonging, either in my own body or in the outside world.

Like most adolescents, I coped by pretending that my epilepsy was not real, that I was not ill. I began to stop taking my anti-convulsants, precipitating more seizures. I withdrew from my life and sought refuge in a world of books that was infinitely kinder and calmer than the one outside. My friendships dwindled.

My mind was in open revolt, and my body the battlefield.

Then my body began to react to the stresses of living with chronic illness with what the doctors then called ‘pseudo-seizures’ (today known as psychogenic non-epileptic seizures). To me, these felt like any other seizures caused by misfiring neurons, and had the same enervating effect on my body, leaving me exhausted.

But my ‘pseudo-seizures’ were the result of the psychological stresses of coming to terms with epilepsy in a society that stigmatised and demonised difference. My mind was in open revolt, and my body the battlefield.

A condition between the mind and the body

My experience of seizures and ‘pseudo-seizures’ highlighted the connections between mind and body in epilepsy. But looking back at the history of medicine, I discovered that epilepsy has always been in that awkward space between the mental and the physical.

The history of medicine reveals that at least some practitioners sought physical explanations for seizures, even though most people thought they had a supernatural cause.

In Ayurvedic texts (c. 1000–800 BCE), the condition identified as Apasmara was characterised by seizures and a loss of consciousness, resulting from the imbalance of the three bodily elements, or doshas – kapha, pitta and vata. The ancient Greek Hippocratic corpus (c. fifth century BCE) also recognised epilepsy as a physical condition caused by an excess of one of the four humours, phlegm.

A woodblock from a 16th-century German alchemical text, representing the four humours: phlegm, blood, yellow bile and black bile.

Medieval Islamic medicine drew on the Greco-Roman humoural system and believed that the origins of seizures lay in the brain and nerves, and were the result of an imbalance of phlegm or black bile.

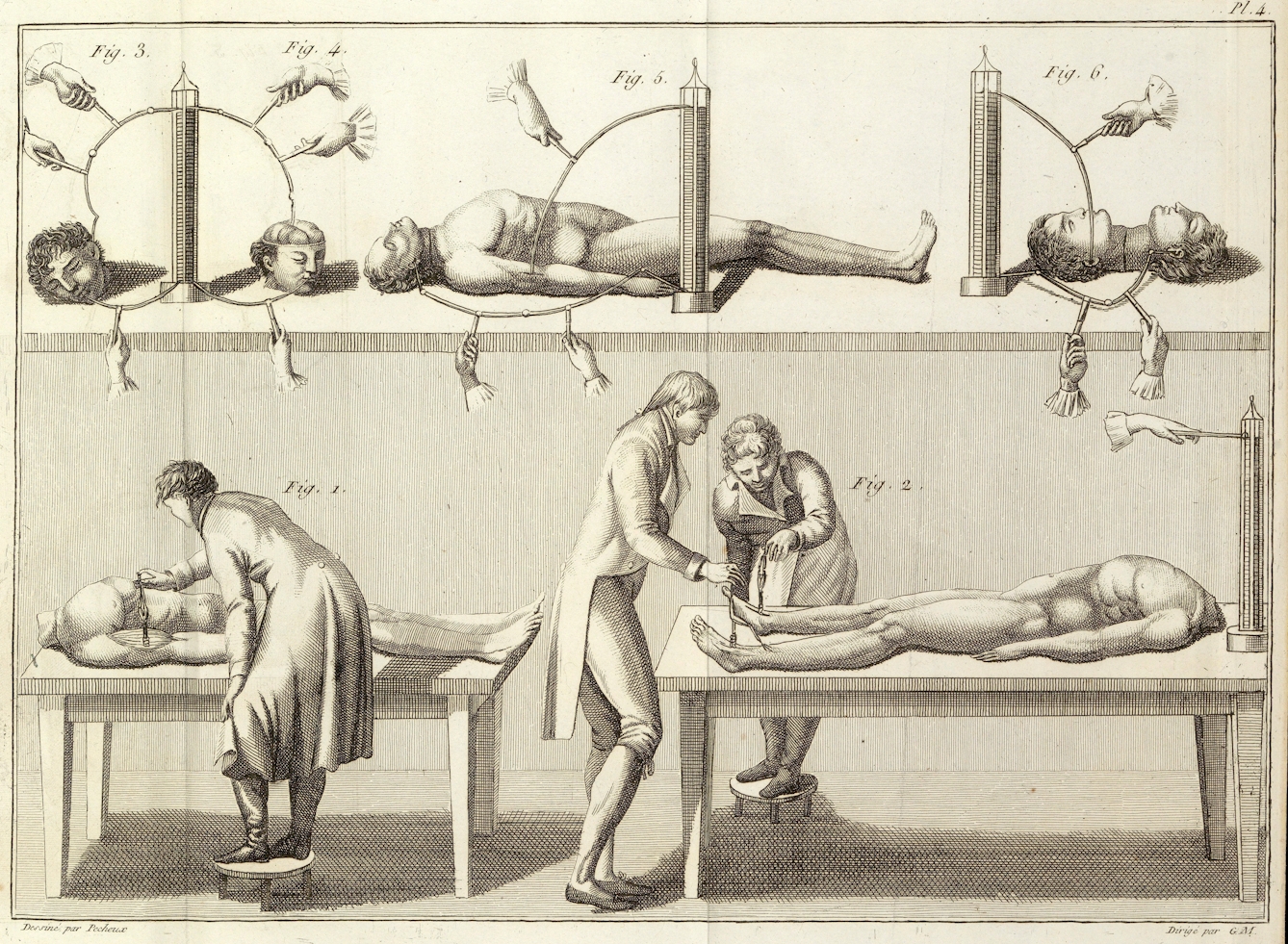

A significant shift in the understanding of types of seizures and epilepsies came in the 19th century. Building on the work of Italian physician and scientist Luigi Galvani (1737–98) on animal electricity, researchers began detailed investigations into bioelectricity, particularly the electrical impulses of the nervous system and the brain.

‘Galvanism’, the science of animal electricity, first developed by Luigi Galvani (1737–98).

The modern medical understanding of epilepsy is based on the work of British physician John Hughlings Jackson (1835–1911) and others. Jackson clarified the nature of a seizure or ‘convulsion’ as “but a symptom and implies only that there is an occasional, an excessive and a disorderly [electrical] discharge of nerve tissue on muscles”.

Scientific experimentation on animals and humans further established the electrical excitability of the cortex of the brain and a distinction was made between epileptic and non-epileptic seizures.

Diagram of a neuron, the brain cell that emits and receives electrical signals from the nervous system.

Despite the growing understanding of the neuroanatomy of seizures, medical texts continued to frame epilepsy as producing “feeble-mindedness” and the result of masturbation, sexual depravity or alcoholism. ‘Epileptics’ were often described as sexually licentious, immoral and untrustworthy and often committed to mental asylums.

Containing epilepsy in the epileptic colony

Epilepsy was often conflated with mental illness and 'epileptics were frequently committed to segregated wards in the asylum. The epileptic ‘colony’ emerged in the context of reforms in the treatment of mental illness in the first half of the 19th century and a desire to find dedicated spaces for the “sane epileptic”. The earliest known epileptic colony was Anstalt Bethel in Bielefeld, Germany, established in 1867, but similar institutions slowly spread across Europe and the United States.

But although the colonies were designed to provide an alternative to the mental asylum, they followed many of the same practices. They emphasised the value of work (usually agricultural labour and trades) as both therapeutic and a way for inmates to contribute to the cost of their care. And inmates were isolated as much to protect the outside world from their dangerous presence as to provide them with a safe home.

A group of epilepsy patients peeling vegetables outside a building at the Craig Epileptic Colony, Buffalo, New York, 1898.

A brochure produced to raise funds and elicit support to provide an epileptic colony in Illinois in 1912 lists the benefits as: “Employment, Association, Recreation, Enables Patients to Help Themselves”. But in a section headed ‘Dangers to Others’ it suggests a more sinister reason for isolating people with epilepsy:

“Criminal instincts develop. Physically an epileptic is strong, and his sexual instincts are often abnormally developed. He frequently becomes a menace to women and children.” And for girls, “the nervous and mental condition often breaks down their normal constraints”.

Despite the altruistic claims, the colony retained the controls of the asylum, segregating inmates by gender and policing their sexuality. Residents were also subjected to various medical experiments and procedures, including those informed by the new science of eugenics, which aimed to ‘breed out’ undesirable diseases or characteristics.

Reading these histories, I am often struck by how the growing medical understanding of epilepsy as a physical condition seemed to make little difference to the notion of epilepsy as dangerous, a threat to mind, body and, indeed, to wider society. This held true even among the medical practitioners who treated and cared for people with epilepsy.

About the contributors

Aparna Nair

Dr Aparna Nair is an assistant professor in the Department of History of Science at the University of Oklahoma. She works on disability, medicine and colonialism in India in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as disability in popular culture and the experience of epilepsy in South India.

Tracy Satchwill

Tracy Satchwill was born in London, grew up in South Wales and is now based in Norfolk. Working across film, collage, photography and installation, her art practice explores female power, reflecting on its removal or reclamation. She weaves personal narratives into her work, exploring identity, oppression and vulnerability to combine the feminine with the surreal, the uncanny and the weird. Satchwill has exhibited at galleries and institutions across the UK and internationally. She also works on public commissions and residencies, focusing on women’s experiences.