Aparna’s husband reacted violently to her epilepsy. After her abusive marriage ended, she sought reasons for his prejudice and anger. Shockingly, she discovered a history in which both science and legislation were used to stigmatise and reject people like her.

The ‘undesirable epileptic’

Words by Aparna Nairartwork by Tracy Satchwillaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

At the age of 22 I found myself in an airless, dreary and packed family court in India. My violent and abusive marriage was coming to an end. My husband couldn’t stand the fact that I was an ‘epileptic’. He believed that he deserved to be compensated with a dowry for marrying a ‘sick woman’.

I refused and filed for divorce. As the judge asked me if I could “just try a little harder to live with my husband”, the violence of my marriage flashed through my mind. “No,” I said quietly. And so it ended.

Years later, I tried to make sense of this part of my life in the only way I knew how – by looking back at history for answers. I wondered what had made people so fearful, and willing to reject those with epilepsy.

Stigma sanctified by law

In India, the abasement and rejection of people who had seizures was enshrined in ancient religious legal texts like the Hindu Dharmaśhāstras. Although written centuries ago, these texts continued to influence laws and customs well into the 19th century, and even in the 20th century. The Hindu Marriage Act (1955) contained a clause that allowed marriages to be annulled if one partner had “recurrent attacks of insanity or epilepsy”. The act was only repealed at the end of 1999. This legal and social sanctioning of stigma and prejudice has always bemused me.

But people with epilepsy have been stigmatised and rejected by science as well as religion. In the transnational eugenics movements of the 20th century, epilepsy was one of the conditions considered a weakness in the human race, which should be limited and prevented in future generations.

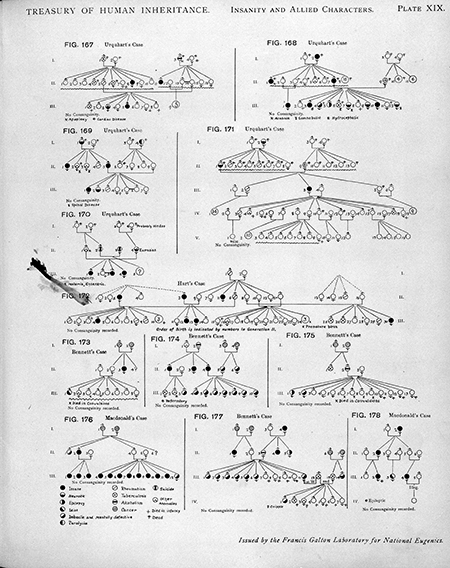

From the 1909 ‘Treasury of Human Inheritance’, family trees showing inheritance for “insanity and allied characters”.

Epilepsy and the ‘science’ of eugenics

Eugenics was developed by 19th-century statistician Francis Galton as a scientific approach to improving the human race through selective breeding. According to the proponents of eugenics, desirable hereditary traits, such as physical prowess and intelligence, should be perpetuated in human populations, while ‘dysgenic’ traits, which included diseases and conditions such as epilepsy, should be eliminated.

In order to prevent ‘bad traits’ such as epilepsy from passing into the next generation, people who already had such traits were discouraged or prevented from having children, either through birth control or by social engineering. In practice such measures included campaigns for practising birth control targeted at certain populations, voluntary and compulsory sterilisation, and, ultimately, euthanasia.

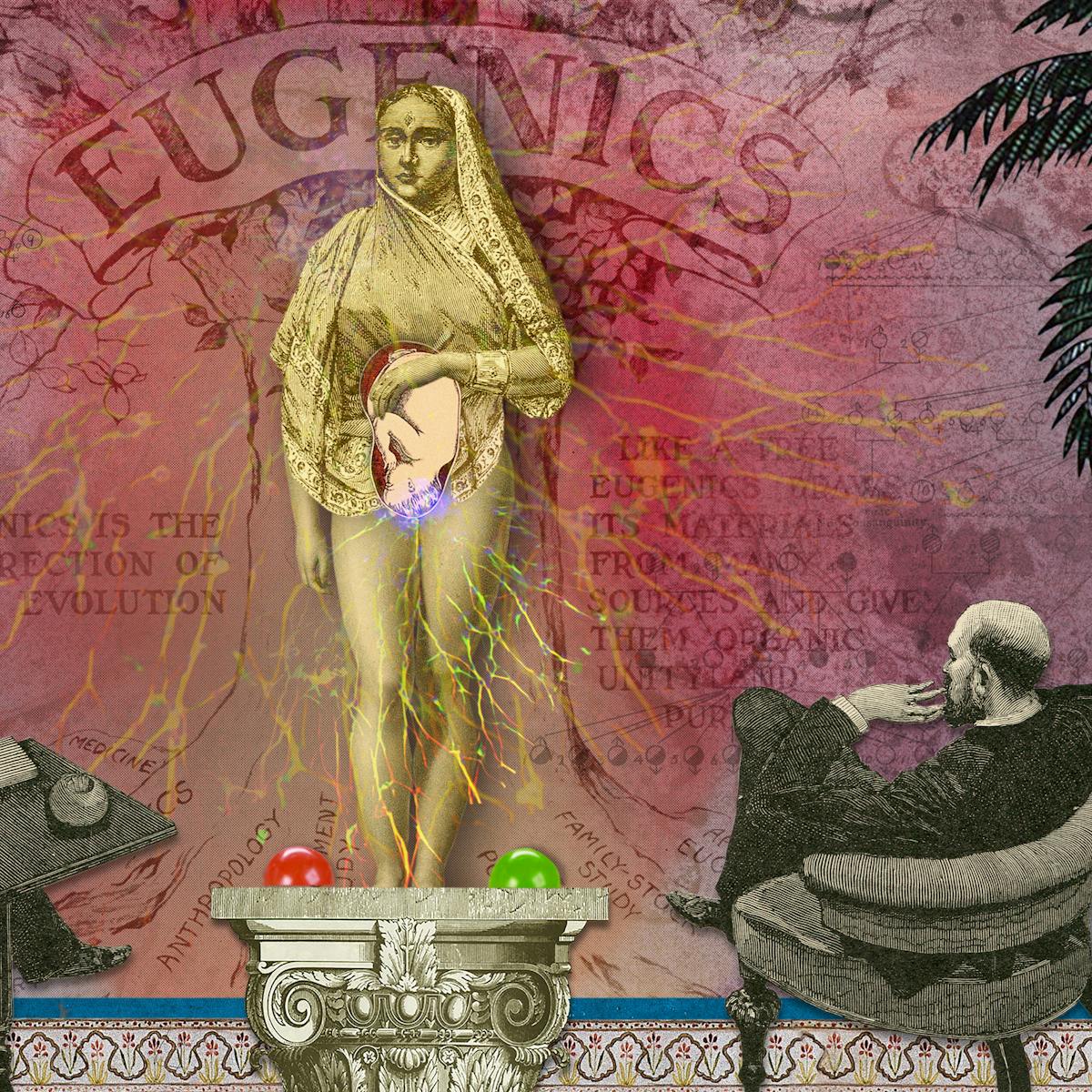

An image from the Eugenics Society archive, used in the organisation’s early 20th-century propaganda activities.

Many scientists and doctors around the world accepted the tenets of eugenics and saw it as a scientific solution to the social problems of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Harvard neurologist and the president of the International League Against Epilepsy, Professor William Lennox, was another example of a medical man who treated people with epilepsy at his clinic and saw no contradiction in advocating eugenic ‘solutions’ for epilepsy. He believed that the best way to rid the world of epilepsy was to prevent ‘epileptics’ from having children. In his own chilling words:

“Let us imagine that we have arrived at the land of ‘could be’ in the year 2048. Thanks to intelligently applied eugenics, […] epileptics are less numerous than a century ago. Also, heeding at last the injunction of Christ, ‘Be ye merciful,’ imbecile epileptics are no longer kept alive to endure a meaningless and miserable existence. Freed of these mindless lumps of flesh in human form, and staffed with adequately trained medical and social workers, institutions are no longer just stagnant pools of patients.”

Epilepsy and legislation

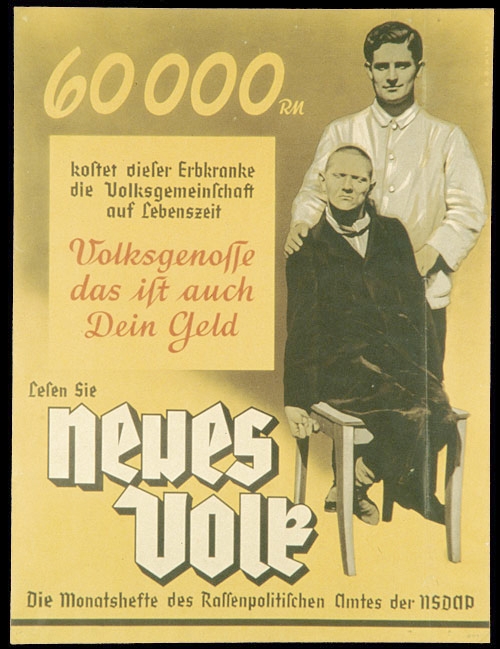

Nazi Germany saw the systematic implementation of eugenic principles targeting disabled and chronically ill people (described as “useless eaters”). The 1933 Law for the Prevention of Offspring With Hereditary Diseases sought the eradication of disability and disease through mass sterilisation of those identified as incurable or having certain diseases or conditions. ‘Feeble-mindedness’ was the most common criterion for forced sterilisation, and epilepsy was the third most common.

Ultimately, the Nazi eugenics policies led to the murder of thousands of people in a programme called Aktion T4 in which doctors and asylum superintendents across the country identified ‘incurable’ patients to be killed.

In this poster promoting the Nazi magazine Neues Volk, the caption reads: “This hereditarily ill person will cost our national community 60,000 Reichsmarks over the course of his lifetime. Citizen, this is your money.” 1938.

Eugenic sentiments influenced civil and criminal legislation in many parts of the world, not just Nazi Germany, and shaped attitudes towards epilepsy. In the United Kingdom, the 1937 Matrimonial Causes Act stated that a marriage could be rendered null and void if “either party were at the time of the marriage of unsound mind, or a mental defective... or subject to recurrent fits of epilepsy”.

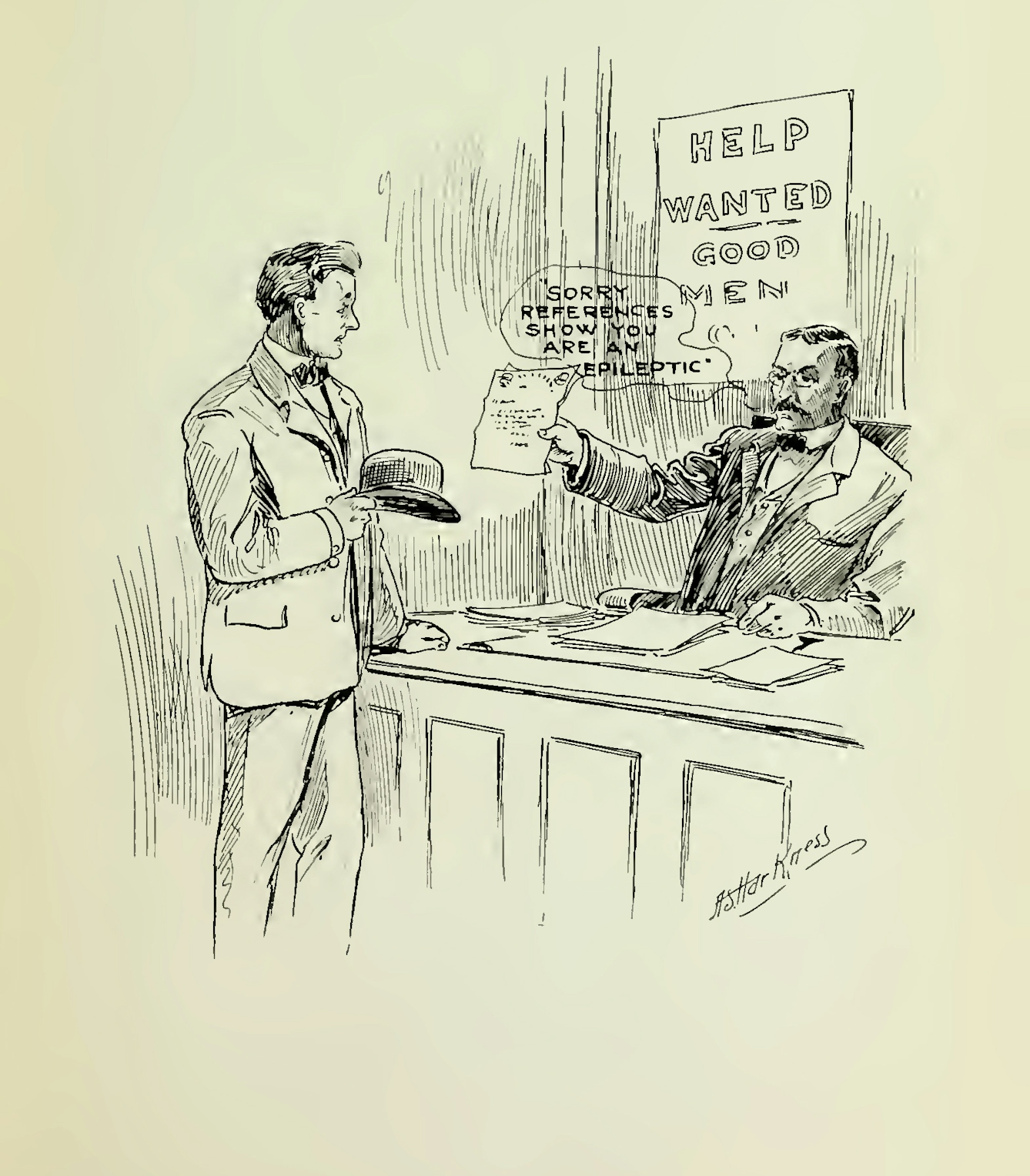

In the United States, people with epilepsy were refused the right to marry in several states and were among the groups targeted by the so-called ‘ugly laws’, which allowed disabled people in public spaces who were deemed to be unsightly or disruptive to be locked up. Although the majority of these laws were later repealed, they legally sanctioned the discrimination and isolation of people with epilepsy and stopped them from participating in many aspects of everyday life.

“I can’t get work. No one will have me when they find out. My friends avoid me.” An illustration depicting the prejudice experienced by people with epilepsy, published 1913.

Another area of policy and legislation influenced by eugenics was immigration. Immigration laws in the United Kingdom, United States and Australia in the early 20th century were explicitly designed to exclude migrants with a host of health conditions, both contagious and non-contagious.

In the United States, immigration law kept out entire families if a single child in the family had been diagnosed with epilepsy. In Australia, successive immigration acts ensured that ‘epileptics’ were disqualified from migrating to the country until 1989.

I was deeply disturbed and saddened by the histories I uncovered, and I am not sure I have ever come to terms with them. Every time I read about them, I am reminded of how science and legislation were used to sanction and marginalise bodies like mine. Every time I think about the most difficult moments in my past, I am reminded of how my experience was inextricably shaped by these histories.

About the contributors

Aparna Nair

Dr Aparna Nair is an assistant professor in the Department of History of Science at the University of Oklahoma. She works on disability, medicine and colonialism in India in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as disability in popular culture and the experience of epilepsy in South India.

Tracy Satchwill

Tracy Satchwill was born in London, grew up in South Wales and is now based in Norfolk. Working across film, collage, photography and installation, her art practice explores female power, reflecting on its removal or reclamation. She weaves personal narratives into her work, exploring identity, oppression and vulnerability to combine the feminine with the surreal, the uncanny and the weird. Satchwill has exhibited at galleries and institutions across the UK and internationally. She also works on public commissions and residencies, focusing on women’s experiences.