It was a jarring experience for Aparna Nair to see for the first time how epilepsy is portrayed on the screen. From flawed outsiders in literature to the cold voyeurism of medical photography, there are few sympathetic representations of the experience of having a seizure or of the toll taken by living with epilepsy.

The ‘epileptic’ in art and science

Words by Aparna Nairartwork by Tracy Satchwillaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

The first time I saw a representation on screen of someone with epilepsy was when a character played by the Malayalam actress Shalini had seizure in a film, the name of which I have long forgotten. Her character, explicitly identified as having epilepsy, was childish and immature, and her illness defined her choices, moods and temperament. Although I had been diagnosed for a few years by then, it still shook me, and my first thoughts were: “Is that how people see me?”

Seizures are surprisingly widespread in popular culture, though not necessarily linked to epilepsy. They are, however, routinely connected to the supernatural, for instance in films that depict demonic, angelic or spirit possession, where the seizure often represents the exact moment that the entity enters the body.

‘Epileptic’ villains and outsiders

Nineteenth-century Western literature has multiple representations of seizures and epilepsy, which is perhaps unsurprising given the growing medical understanding of the condition at the time. For example, the English novelist Wilkie Collins gives a very detailed and graphic description of a seizure in his book ‘Poor Miss Finch’ (1872). Oscar, the villain of the piece, has what is described as an “epileptic fit”:

“A frightful contortion fastened itself on Oscar’s face. His eyes turned up hideously. From head to foot his whole body was wrenched round, as if giant hands had twisted it, towards the right. Before I could speak, he was in convulsions on the floor at his doctor’s feet.”

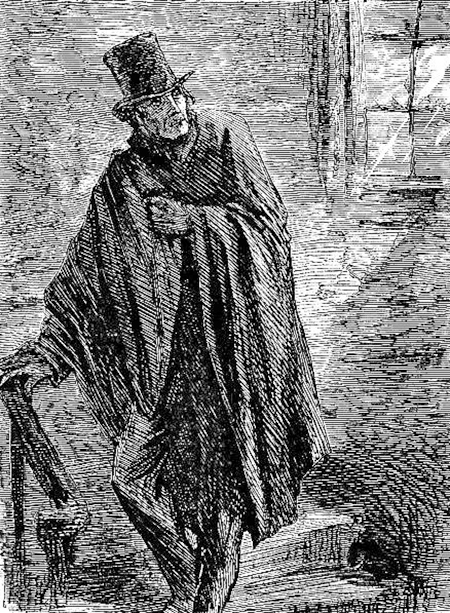

In the popular understanding of the age, the ‘epileptic’ was especially prone to criminal or violent behaviour as well as moral depravity and sexual indulgences or perversions. Charles Dickens is another author whose villain in ‘Oliver Twist’, Oliver’s wicked half-brother Monks, is literally marked by the scars of his epilepsy: “His lips are often discoloured and disfigured with the marks of teeth, for he has desperate fits.”

Later in the book, epilepsy is identified as the cause of both his appearance and his wickedness: “You… in whom all evil passions, vice, and profligacy festered, till they found a vent in a hideous disease which has made your face an index even to your mind.” Epilepsy is thus constructed as profoundly dangerous, a marker of criminality, immorality and villainy.

Monks is depicted as a sinister figure lurking in shadow in this illustration by Sol Eytinge Jr for an 1867 edition of ‘Oliver Twist’.

But the Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s book ‘The Idiot’ gives a different perspective. The ironic title refers to a profoundly good, gentle and honest hero whose simplicity and openness are seen as weakness by those around him. The hero, Prince Myshkin, has been in a sanatorium for his illness, and his seizures encourage the other characters to paint him as the ‘idiot’ of the title.

Dostoevsky’s portrayal of prejudice and misunderstanding around seizures and epilepsy in the 19th century is interesting precisely because the author himself lived with seizures. But what draws me to Myshkin is that despite being an ‘outsider’ in his own world, he retains his decency and faith in humanity.

'Epileptics' through the medical lens

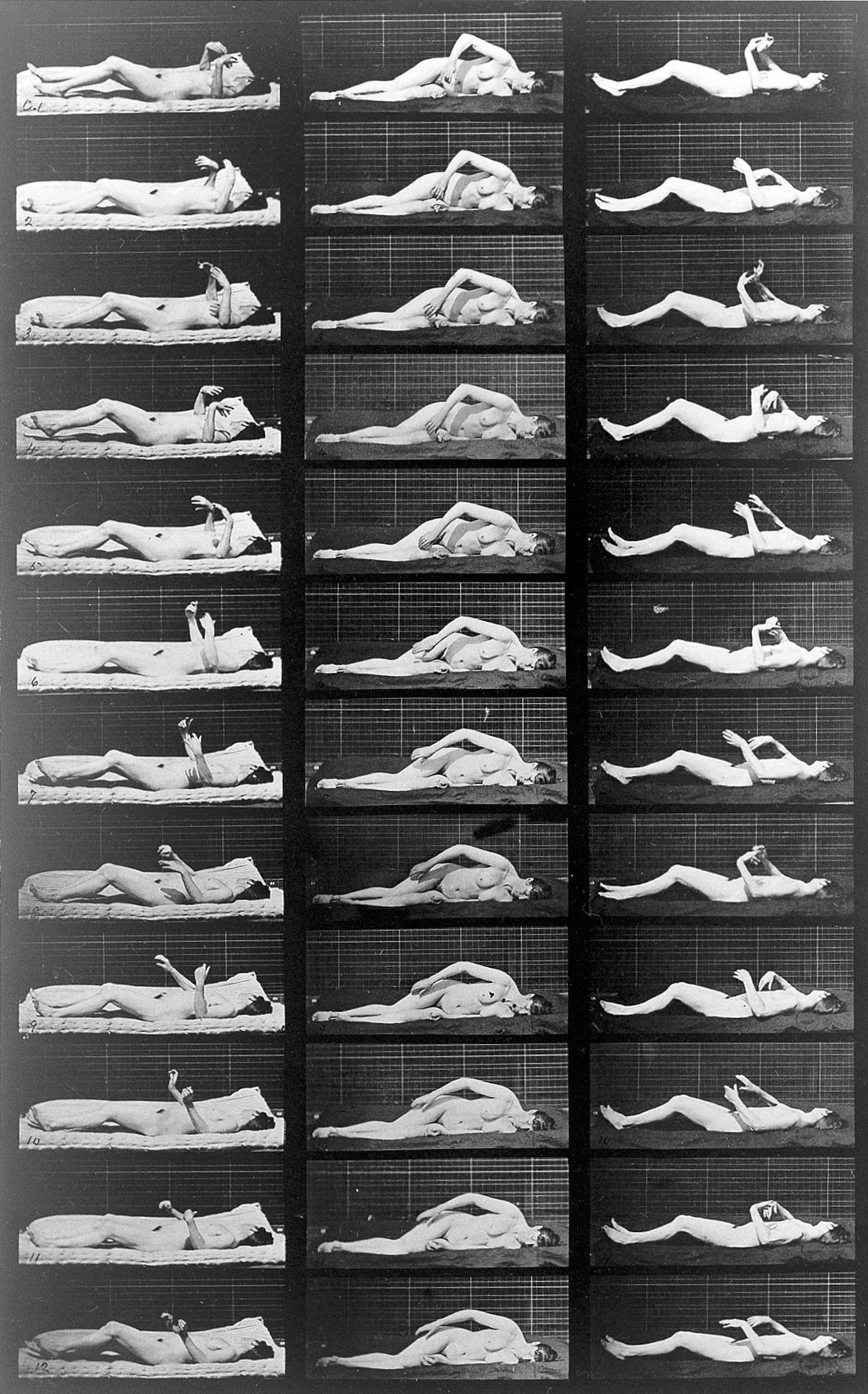

In the 1870s Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) created several series of photographs of people with different physical conditions, including epilepsy, when doctors offered him the “opportunity of photographing various patients under their care”. The figures in the photographs are anonymous. The nudity and stark framing of their bodies contribute to the photographer’s effort to highlight their fundamental differences from those considered ‘normal’.

I linger over the set of 36 photographs depicting a nude woman lying on the ground having a seizure. In the first 12, her face is turned away from us, but her hands twist, jerk and curl as the viewer’s gaze moves from image to image. In the next twelve images, she lies on her side, eyes closed and body limp as her arms continue to twist and convulse.

The series of 36 photographs of a woman having an induced ‘convulsion’ or seizure; part of Eadweard Muybridge’s ‘Animal Locomotion’ series.

Fortunately, not much is visible of her face, as she presses it into the cloth on which she lies. I find myself relieved at that. I am afraid of what I might see. But I imagine I know what those tightly clenched eyes conceal: bone-deep exhaustion, confusion, panic and fear. The loss of self so brutally captured in the photographer’s gaze and by the camera.

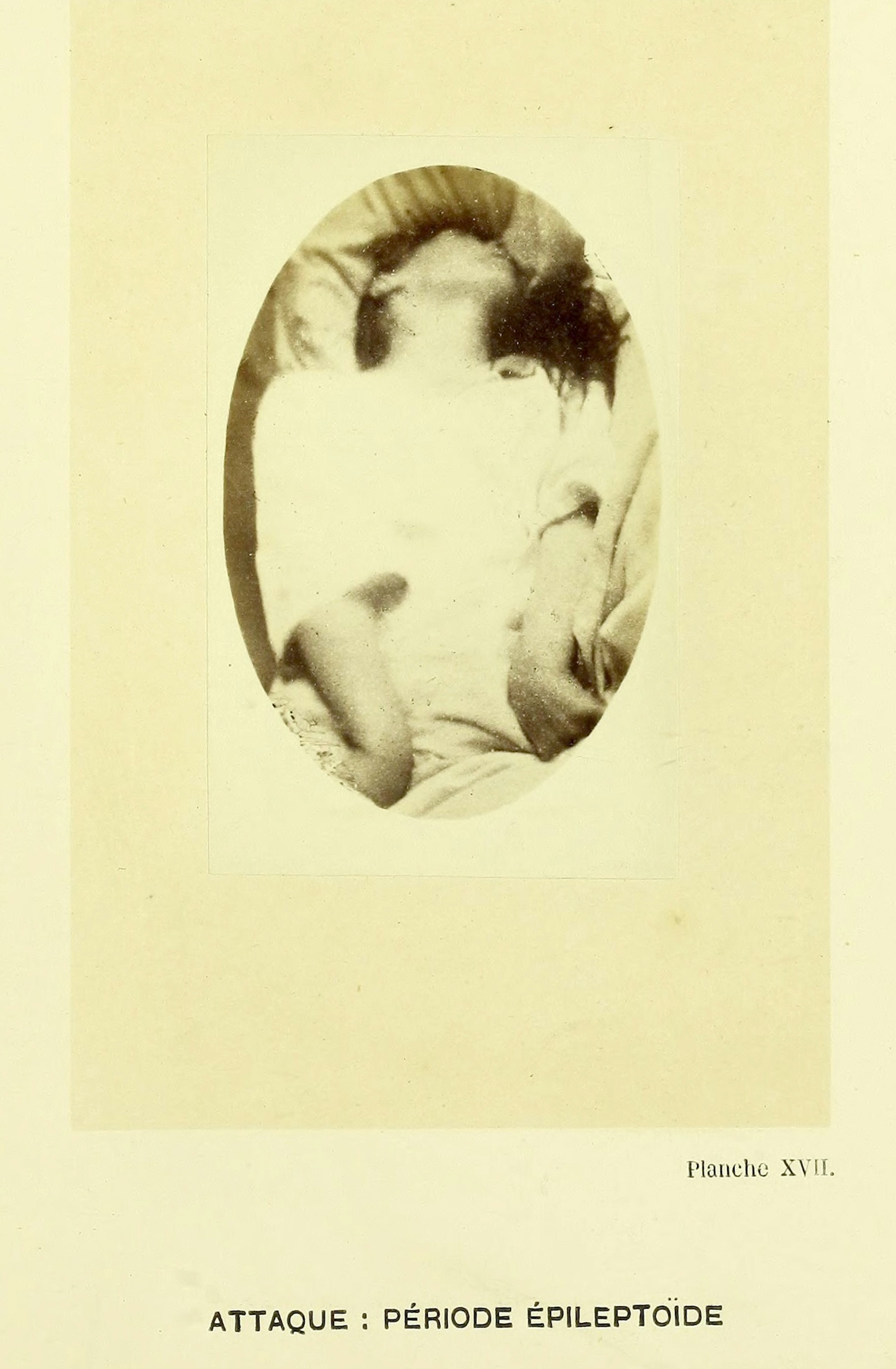

At the beginning of the 20th century neurologists at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris and the Craig Epileptic Colony in New York were among the first to use film to capture the body during a seizure. The results were called the ‘Epilepsy Biographs’, complete cinematic case studies of the disease.

A woman having a seizure. From ‘Iconographie photographique de la Salpêtrière’ 1876–80 by Paul Regnard, a doctor at the hospital.

The ‘Epilepsy Biographs’ were intended to be educational films for the medical community and form part of the modern medical construction of epilepsy. They share the same sparse aesthetic as Muybridge’s work, with a dark backdrop, sometimes featuring the arms of a white-coated attendant or two positioning the seizing – sometimes limp, sometimes stiff – body of the subject. These biographs are also a profound reminder of the surveillance of epileptic bodies in hospitals and spaces like the colony.

These early representations of epilepsy through the scientific or medical gaze may not have been intended to be seen by the wider public, but you can’t help feeling that the stark, distant portrayals would have informed the voyeuristic representations of people having seizures so common in popular culture.

Epilepsy as a shared experience

Some recent film representations of epilepsy have tried to give more honest representations of the condition. What endeared the film ‘Electricity’ (2014) to me – in which a young girl searches for her brother – was its use of special effects to immerse the viewer in the sensory perception of a seizure, which is often so hard for us to communicate. Instead of watching from the outside, the viewer is invited to share the experience.

The 2007 biopic of the post-punk band Joy Division and its lead singer Ian Curtis, ‘Control’, is as much a tribute to the music as it is about Curtis’s struggles with epilepsy and depression. These feed his lyrics and, sadly, consume him at the end, when he takes his life in a moment of darkness. Despite its bleakness, ‘Control’ has always struck me as uniquely real in its portrayal of the toll that results from living with the fear and stigma around epilepsy.

Poster for the 2007 film ‘Control’, starring Sam Riley as Joy Division’s Ian Curtis.

The lyrics of the Joy Division song ‘Disorder’ are about depression rather than epilepsy, but if you live with the condition, you might also recognise in them the spiralling-out of a seizure:

“It’s getting faster, moving faster now, it’s getting out of hand,

On the tenth floor, down the back stairs, it’s a no man’s land,

Lights are flashing, cars are crashing, getting frequent now,

I’ve got the spirit, lose the feeling, let it out somehow.”

About the contributors

Aparna Nair

Dr Aparna Nair is an assistant professor in the Department of History of Science at the University of Oklahoma. She works on disability, medicine and colonialism in India in the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as disability in popular culture and the experience of epilepsy in South India.

Tracy Satchwill

Tracy Satchwill was born in London, grew up in South Wales and is now based in Norfolk. Working across film, collage, photography and installation, her art practice explores female power, reflecting on its removal or reclamation. She weaves personal narratives into her work, exploring identity, oppression and vulnerability to combine the feminine with the surreal, the uncanny and the weird. Satchwill has exhibited at galleries and institutions across the UK and internationally. She also works on public commissions and residencies, focusing on women’s experiences.