In a time without scans or antenatal tests, neither medical staff nor parents were prepared for the damage to the foetus caused by thalidomide. And in the aftermath of the birth, mothers were often left isolated and waiting for days to find out what had happened to their baby.

Thalidomide babies

Words by Ruth Blueartwork by Hollie Chastainaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

No one was prepared for the birth of thousands of babies who had been affected by thalidomide whilst still in the womb. The severely limited clinical trials of the compound meant there was no warning of the devastating effect it would have when given to women during pregnancy. And even when that became clear, there was a reluctance to share information and offer support, both within the medical profession and to the families affected.

Today, scans and antenatal checks provide a detailed insight into an unborn child’s physiology, sex and overall health before birth. In the late 1950s and early 1960s these did not exist. It was a time when patients, especially pregnant women, had very little control over their treatment and few opportunities to voice their concerns.

If parents were unprepared for thalidomide babies, so, it seems, were many of the doctors and nurses who delivered them. Margaret recalled that when her son Brian was born, the hospital staff were in a state of shock. He was taken away before she could see him and no one told her anything until a doctor came later and said, “There’s something wrong with your baby.”

While the nurses brought other babies to see their mothers in the ward, Margaret was left alone until she eventually asked a nurse about her baby. Only then was she taken to see him, lying untended in a cot. This was three days after giving birth.

Margaret.

Mothers left in isolation

After a very difficult labour at home on a hot August day, Beatrice finally gave birth, but she was sedated before she could see her baby, and when she awoke, the baby had been taken to hospital in an ambulance accompanied by her husband.

It was left to Beatrice’s husband, on his return from the hospital, to tell her that they had a little boy and that he had been born with no arms or legs. All the baby’s things had been cleared away without her knowledge because they did not expect him to live. Beatrice first saw her baby when she went to the hospital three days later.

Beatrice.

It was not uncommon, as in Beatrice’s case, for the mother to be sedated and kept from seeing their child for hours or even days. Sometimes the father was ‘shown’ the baby first and then left to describe the impairments to the mother. But the most common experience was for the mother to be presented with her swaddled child and left alone to ‘unwrap’ it.

This was Winnie’s experience when she returned from the toilet to find her swaddled baby left on her hospital bed. Her incomprehension about what happened is heartbreaking:

“I can understand them not wanting to tell me; I can understand it would be difficult for them. But the shock of just not anybody mentioning that there might be something wrong with him – you know, not giving any warning – and you just unwrapping the shawl and finding him...”

Frequently, tearful mothers, left alone, assessed the ‘damage’, counting fingers and toes and working out for themselves what to do next. One mother described how she was glad her daughter had three fingers so that there was “enough for one to wear a ring on, if she wants to get married”.

Overcoming the stigma of disability

When Thelma, who was a doctor herself, was told by the obstetrician that her baby “was not normal”, she prepared herself to see the “foetal monster” she had read about in reports on thalidomide. But instead, she was thrilled to see “the most gorgeous baby you’ve ever seen in your life, only five pounds, tiny, with little chicken-wing arms”.

But her delight at her new daughter was not shared by the obstetrician or her husband, who could not understand how she could be pleased to have a disabled child.

“Thelma prepared herself to see the ‘foetal monster’ she had read about in reports, but instead, she was thrilled to see ‘the most gorgeous baby you’ve ever seen in your life’.”

This was a time when attitudes to disability were largely negative and blame was often attached to the parents. Disability had frequently been, to some degree, associated with parents’ lifestyles or “bad genes”. In addition, some men blamed their wives – why had they taken it? Mothers blamed themselves, or their husbands for encouraging them to take the drug so that they could continue to fulfil their functions as wife and mother.

And families were understandably concerned for the future of their children. Disabled people were often excluded from society, and disabled children were routinely placed in institutions or sometimes hidden away quietly at home.

Mercy killings?

There are numerous accounts of so-called ‘mercy killings’, when it was thought that a baby was too severely damaged to survive for long or would have an intolerable quality of life. The number of such deaths will never be known for certain, but there is enough evidence to indicate that this kind of euthanasia did happen.

One anonymous father remembers experiencing this:

“Well, when she came, everyone, of course, was shocked... she was only about eight inches, nine inches long; there was one arm and one leg and another one curled up, and it was just a dreadful thing. So [the doctors] first of all said well, you know, we’re not going to do anything and we’ll let her die. They tried to… perhaps it was for fresh air, the window was opened, and she was put out, unclothed, outside on the windowsill.

“She refused to die and basically from that time on we said, ‘Well, you know, she’s our daughter.’ And that was it, she was brought up.”

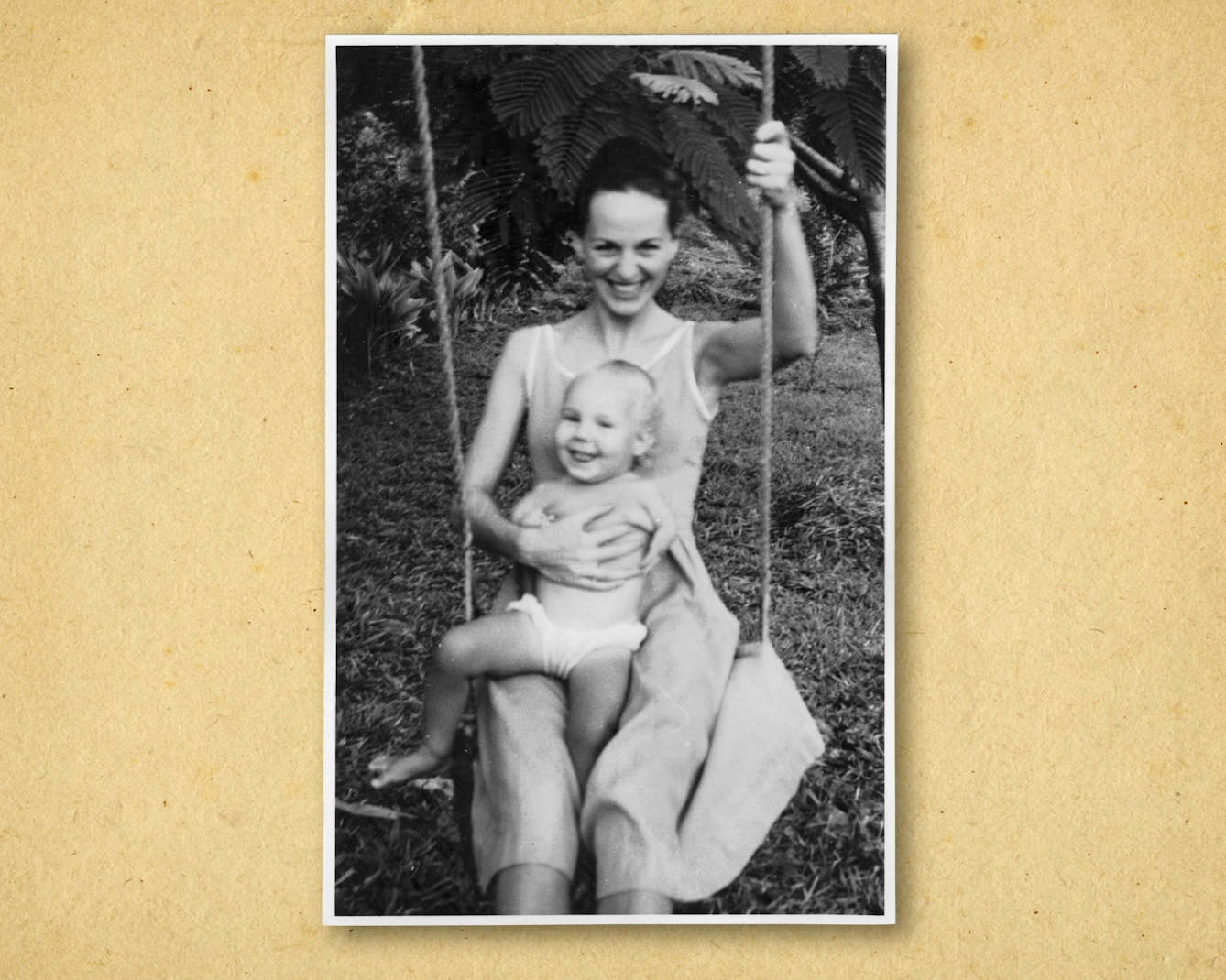

Jenny was determined to raise her daughter Carolyn as though she were not disabled, and for most of her childhood, Carolyn never considered herself to have a disability.

The same concern must have crossed Beatrice’s mind when she went to the hospital to collect her baby after three days. She found him left outside in a pram with his face badly sunburned. And she turned to her husband and said, “Right, we get him home as quick as possible – they don’t care!”

Coming to terms with a thalidomide baby

When thalidomide babies survived, they were either sent to special institutions or returned to the family home with minimal or no intervention from medical staff. After the initial shock and trauma of the birth, many parents had their eyes opened to the limited support and understanding that would become a recurring theme in their battles to give their child a decent life.

Parents who resisted the encouragement of medical staff to put their baby into an institution had to restructure their lives to accommodate a disabled child. They had to explain to siblings, relatives and friends as best they could what had happened to the baby. Pearl had to find a way to tell her four sons about their new baby sister and let them choose whether to keep her at home or send her away.

Pearl.

There are many such accounts of how families pulled together and overcame their guilt and confusion to give their child a fighting chance at a life filled with love and fulfilment.

About the contributors

Ruth Blue

Dr Ruth Blue is a freelance writer, researcher and oral historian with a PhD in fine art from the Slade School of Fine Art. She worked for Wellcome for 17 years, where she began working with thalidomide survivors in 2013, collecting their stories, photographs and artefacts. She has continued this work for the Thalidomide Society.

Hollie Chastain

Hollie Chastain is a mixed-media artist and award-winning illustrator living and working in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Coming from both a graphic-design and studio-art background, her work has a storytelling quality, mixing found material, strong graphic elements and modern palettes. Along with gallery work, she has illustrated work for Smithsonian Magazine, Warner Music and the Oxford American, among others, and authored and illustrated a book published in 2017. She currently works from a home studio with her husband Eric, two children, two cats and two dogs.