The UK is home to over 1,000 mega-farms that use intensive methods to increase the volume of dairy products they can sell. This is hugely damaging to the soil and environment, but the rise of a regenerative agriculture movement is pushing back against the mainstream trend. Food writer Angela Hui explores the inextricable link between dairy products and soil health.

Soil health and dairy farming in the UK

Words by Angela Huiartwork by Cat O’Neilaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Article

We’re all familiar with the old saying “you are what you eat”, the notion that in order to be fit and healthy, you need to eat good food. Nutrients provide the foundation of structure and function, from the skin and hair to the muscles, bones, digestive and immune systems. But what if this thinking was applied to cows, and how does the livestock’s diet then affect what we eat (their milk and cheese)?

In the UK, there are over 1,000 intense mega-farms, some housing as many as a million animals. Over the last 50 years, dairy farming has become more intensive and the amount of milk produced by each cow has increased dramatically.

The 2021 UN report on soil pollution shows that industrial farming and poor waste management are poisoning soils, resulting in erosion, compaction and reduced soil health, which has impacted crop fertility, yields and nutritional quality. Human life is dependent on soils, which supply 95 per cent of our food, but the world’s soils are now under unprecedented pressure like never before.

Jimmy Woodrow is executive director at the Pasture-Fed Livestock Association, a British non-profit membership organisation, whose mission is to help livestock farmers move away from the industrial paradigm and help them adapt their businesses for the current climate.

“We teach and help farmers look after their soil, restore biodiversity and deliver nutrient-dense meat and milk. If you’re more profitable, you should be using fewer inputs and prioritising soil health. Healthy soil, frankly, is at the heart of all of it,” he explains.

“Over the last 50 years, dairy farming has become more intensive and the amount of milk produced by each cow has increased dramatically.”

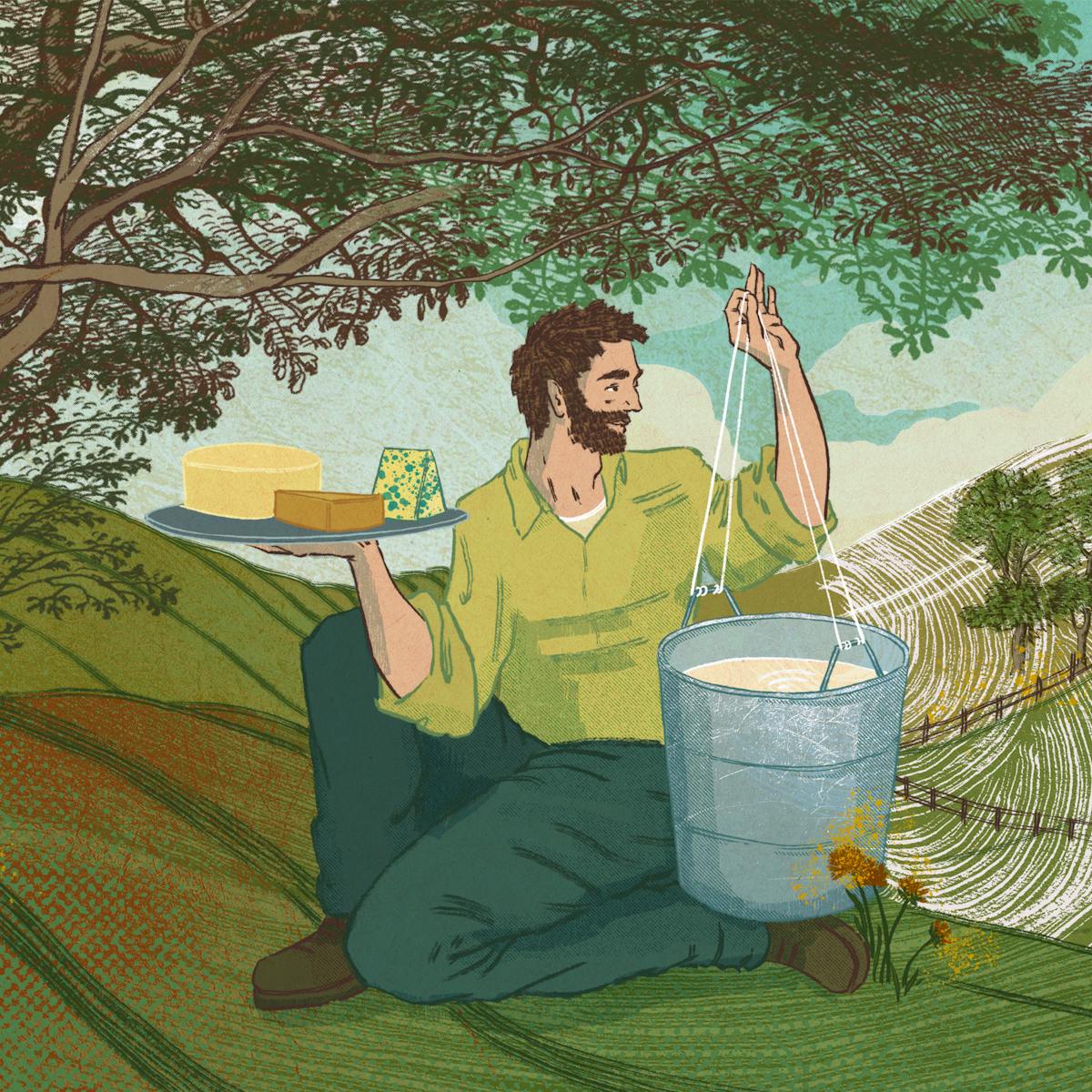

“People need to eat the biodiverse and beautiful landscape that they want to see. If you’re eating the animal or you’re drinking the milk of the animal, you’re getting a representation of that landscape. Terroir [the complete natural environment in which food is produced] has been heavily associated with wine, but increasingly it’s used in things like beer, butter, cheese and milk.”

An organic overhaul

The vast majority of farmers in this country have adopted an intensively industrial model, but a shift is happening. In the last ten years, the regenerative agriculture movement has been growing. It’s an ecological approach to farming that focuses on restoring and improving soil health, increasing biodiversity and promoting sustainable farming practices to rehabilitate and enhance productive ecosystems.

Many farmers have changed their approach to managing land and producing food, and government data shows that in 2021 there were over 5,000 farms registered with the organic certification bodies. The UK’s flagship event for regenerative agriculture, Groundswell, which first took place in 2016, began with a couple of hundred attendees and has now grown to include thousands.

In addition to programmes like Groundswell, regenerative farming groups have witnessed a huge surge. Established in 2014, the Landworkers’ Alliance has over 1,500 farmers and landworker members from across the UK, advocating for regenerative farming practices. Notably, the Nature Friendly Farming Network and the Pasture-Fed Livestock Association together command a network of more than 1,500 farmer members.

After years of using pesticides, poisoning the soil and seeing his crop fields’ productivity crash by a third, David Finlay, owner of Rainton Organic Farm and Cream o' Galloway in Scotland, has completely overhauled the way he works. It’s been a 12-year process that involves a lot of research, development and preparation, as well as trial and error, but Finlay’s efforts are paying off.

Since changing farming methods, his cows’ wellbeing, growth rates and longevity have improved drastically, his soil ecology is now working in harmony with the pasture, and productivity has recovered. The Scottish dairy farm and creamery has become Europe's largest cow-with-calf dairy farm. Unlike most dairy farms, the calves on Finlay’s farm stay with their mum to suckle naturally.

Since changing farming methods, his cows’ wellbeing, growth rates and longevity have improved drastically.

Finlay explains that this method reduces stress levels, and stress impacts reproduction and increases the risk of infections and diseases. Rainton Farm is able to get young stock turning over quicker and is able to produce 25 per cent more milk.

“Many farmers have changed their approach to managing land and producing food.”

“Separating calves from cows is a lot easier for management and disease prevention, as there are fewer complications, but unquestionably you're adding a stress factor to your system of production,” he says. “Yes, the calves drink more milk, but it’s better in the long run. They’re happier and healthier, calves grow ten months sooner and twice as fast before they come to maturity for beef or dairy.”

Soil health and the dairy system

With this shift towards a more holistic and sustainable approach to farming, more farmers are realising the importance of soil health in the dairy system. An example of how an environmental approach to farming is beneficial in a wider sense, the Soil Association’s 2023 Organic Market Report reveals the highest year-on-year growth in 15 years for the UK organic market, where dairy accounts for 27 per cent of the organic market.

The organic industry is now worth £3.1 billion, up 1.6 per cent from the previous year. But it is always a constant challenge. Recently, the dairy industry has been decimated by the war in Ukraine, which has driven up the price of feed and energy.

“The price farmers are being paid at farm gate has reduced, with the organic premium for milking having almost halved in the past two years, while the price of feed has increased significantly,” Adrian Steele, Soil Association Organic Sector Development Advisor, explains.

“Since we started 25 years ago and changed our whole farming system, we’re working towards net zero, and we’ve sequestered over ten tons of carbon per hectare per year,” Finlay says. “We’ve seen a change in insect life and a decline in head flies. The plants and herbage on the farm have evolved.

“Looking out the window, there’s a sea of orange dandelions. To my neighbours, they think they’re weeds, but they’re a valuable part of soil ecology, as they’re deep-rooting plants that bring up nutrients from the depths, help open up the soil and provide nutrient-rich leaves.”

Farmers have long understood that certain foods fed to cows can alter the taste of their milk. The Organic Research Centre found that legumes and herbs have the potential to improve mineral and protein content in grass swards for cattle. Additionally, a recent study shows evidence that increasing forage in dairy diets raises omega-3 in milk, and milk from forage-fed cows contains higher levels of conjugated linoleic acid and omega-3 than conventional whole milk. Both are needed in the human diet to help reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases and other metabolic diseases.

Thinking of future generations

Sarah Appleby, producer of artisan cheeses at Appleby's Dairy in Shropshire, whose family have been making Cheshire cheese at Hawkstone Abbey Farm for three generations, has always focused on balancing good milk production with careful stewardship of the surrounding countryside.

“Looking out the window, there’s a sea of orange dandelions. To my neighbours, they think they’re weeds, but they’re a valuable part of soil ecology.”

“We use a combination of fine pastures, quality unpasteurised milk and hands-on cheesemaking – it’s definitely a more challenging way of making cheese, but it’s really exciting,” she says. “Our cheese would alter through the seasons, depending on what the cows are grazing.

“We're looking at incorporating things that were lost back into our farming through different hedgerows, grasses and clovers. We consider the fats and solids; we mix morning and night milk because the butterfat protein changes throughout the day.”

The connection between soil health and dairy products extends beyond the realms of animal welfare and land stewardship. Now more than ever, the shift towards promoting sustainable agriculture practices and well-managed pastures that prioritise animal welfare can contribute to healthy soil, water conservation, biodiversity and help tackle the climate crisis.

“Being sustainable means being able to produce food not just for next week and next month, but for generations to come,” Appleby says. “The way food is produced has been turned on its head completely. It’s better to work with nature than against it. What’s good for the land is good for cows and what’s good for the cows is good for us.”

About the contributors

Angela Hui

Angela Hui is an author, writer and editor. She was the former food and drink editor at Time Out and lifestyle reporter at HuffPost. Her work has been widely published by the BBC, gal-dem, Guardian, Financial Times, Independent, Lonely Planet, Metro, National Geographic Traveller, Refinery29, Vice, and more.

Cat O’Neil

Cat O’Neil is an award-winning freelance illustrator, specialising in editorial. She studied at the Edinburgh College of Art, graduating in 2011, and has lived in Hong Kong, London, Glasgow, Lyon and Edinburgh. Her clients include the New York Times, Washington Post, WIRED, LA Times, Scientific American, the Financial Times, the Guardian/Observer, Libération and more. Her work explores the use of visual metaphors to convey concept and narrative, and combines the use of traditional and digital mediums. Much of her recent work includes the creation of 3D paper sculptures, which are made in her studio in Edinburgh.