Academics on hallucinogenics, kids sniffing glue, and Scientologists recruiting drug users keen to kick the habit. Revealing stories about experiences of drugs from every angle are brought to light in an archive recently acquired by Wellcome. Archivist Anthony Day talks about attracting readers of all kinds to this fascinating collection.

Sniffing glue and Scientology in the DrugScope archive

Words by Gwendolyn Smith

- Interview

You wouldn’t think an archive about drug addiction and recovery would have much of a light side, but nestled among the sobering stories in Wellcome’s recently acquired DrugScope collection are some unexpectedly amusing tales. One conference report sees a group of philosophers and theologians taking a decidedly ‘Method’ approach to their research on the effect of psychedelic drugs.

“It’s hilarious – these really well-mannered professors end up taking drugs and talking about how extraordinary the carpet looks,” says archivist Anthony Day.

The stark contrast isn’t just between the seemingly buttoned-up dons and the world of psychedelic stimulation – but between the story and the other narratives in the collection, too. “You have academic engagement with drugs and spirituality and the betterment of the soul and so on, and then on the other hand you’ve got a very down-to-earth picture of working-class Britain through information about glue-sniffing.”

Day believes this breadth is one of the collection’s greatest draws. DrugScope was the leading UK organisation representing those working in the drugs field, and its archive, acquired by Wellcome after DrugScope closed in 2015, encompasses an enormous range of material – mainly from the UK and the US – including pamphlets, conference papers and government publications.

More: The blurry lines between safe and dangerous, legal and illegal.

Glue-sniffing in Thatcher’s Britain

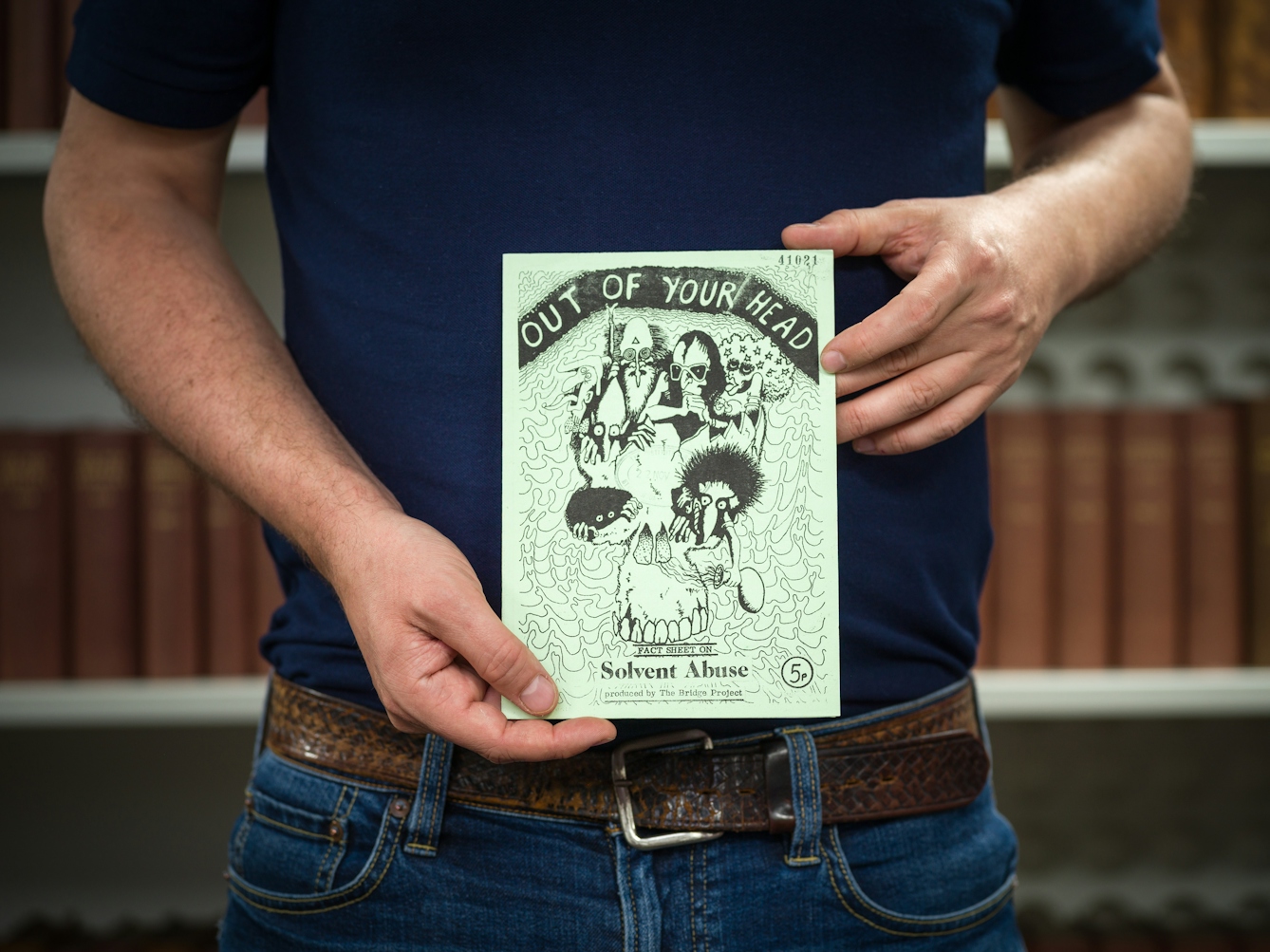

The glue-sniffing subject matter forms one of the most interesting narratives in the collection. “There’s a lot created by working-class youths that’s about their engagement with glue-sniffing and how that intersects with their lack of opportunity and police harassment,” says Day. “It’s very much a picture of Thatcher’s Britain in the 1980s.”

He believes it highlights the moral panic around the issue at the time, along with the chasm between those taking drugs and those telling them not to. Take the zine penned by young people who had been expelled from school, in which they mull over their experiences of doing glue. “It’s very candid and honest, and captures a very particular voice – everything’s written in a phonetic dialect style,” says Day.

Material like this forms a sharp contrast with educational resources for teachers aimed at drug prevention, thereby exposing the lacunae in such initiatives. “They’re saying good things – of course, it’s not a good idea to do glue – but there’s an element of not really tackling the reason why people choose to do drugs in the first place.”

Scientology and psychedelia

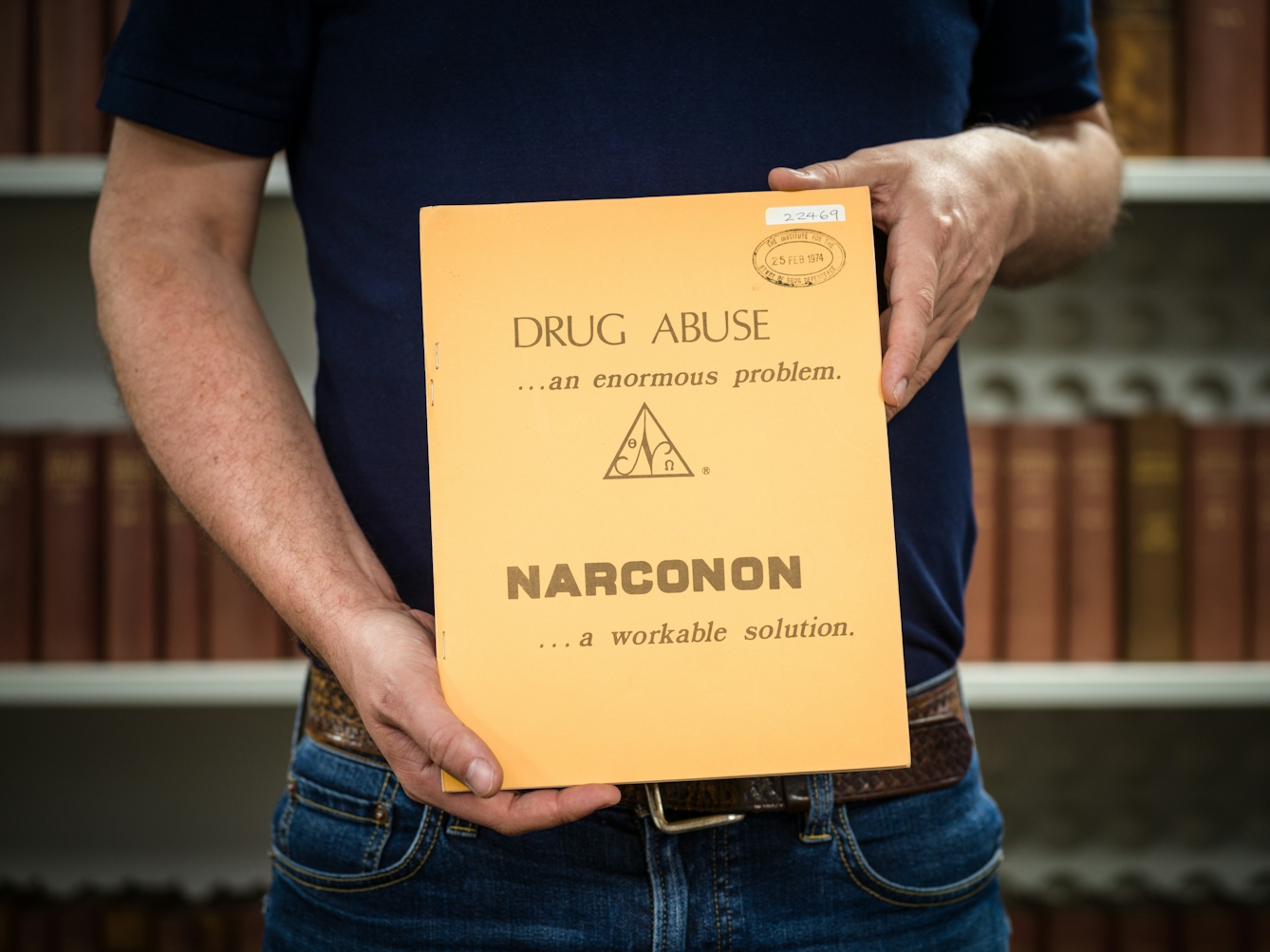

Aside from the sheer range of stories it contained, what surprised Day most about the archive? “The one thing I didn’t know about is an organisation called Narconon.” He came across brochures advertising Narconon’s services to people with drug-addiction problems.

When he started reading these, it became clear it was a Scientology network. As with other materials created by rehab services, he says, “There’ll be a hook or a particular method and they’ve got it sussed, and can say, ‘This is how we’re going to help.’” The brochures “offered a ‘better way’, an idealistic and, in a sense, appealing philosophy”.

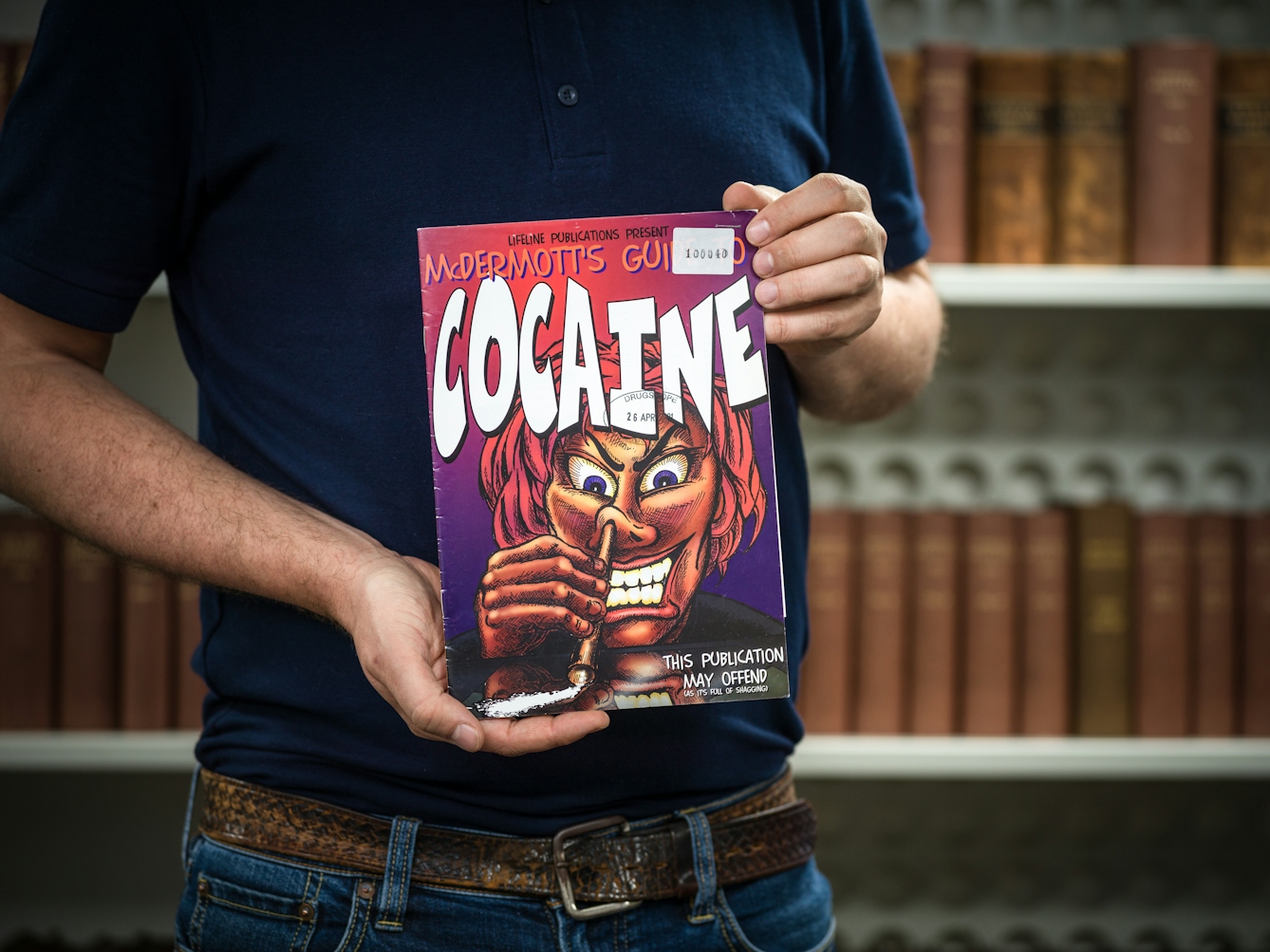

Stealthy advertising tactics are also apparent if you look at the graphic-design element of some of the American material in the archive. Day was particularly absorbed by the use of 1960s’ and 1970s’ psychedelic style. “That design was very grounded in the psychedelic experience, and it’s a very pro-psychedelic thing, and those images were designed to stimulate you when you were high.”

Unsurprisingly, then, he was tickled to find it being used by the US government to present an anti-drugs message; they’d cannily commandeered it with the hope of appealing to the same demographic. “It was interesting to see it both grounded in the counter-cultural moment and then also adopted by a kind of opposite ideology telling kids that life is this wonderful psychedelic journey and you don’t need drugs,” he says.

“What is being said now was also being said 30 or 40 years ago.”

The collection also has plenty to say about the history of the legalisation of drugs for clinical or therapeutic use. Looking at historic conversations around cannabis chimes with how the drug is becoming more accepted today, with cannabidiol (CBD) now found in everything from cosmetics to beer.

“What is being said now was also being said 30 or 40 years ago,” says Day. “Clearly, it takes time to shift such a monolithic idea. Politicians have to find the right time to discuss these things: they’re up against Middle England and the Brexit brigade – you have a very fearful demographic that you have to appeal to.”

Day also came across “a big culture of newsletters and pamphlets – short things that were essentially blog posts or articles you might post online”. This offers a glimpse into how drugs professionals communicated before the internet. “It shows how these grassroots organisations were forming forum-like communities among their readership – and also how that readership could interact through letters.”

Making archives more accessible

What drew him to the archive originally? He says it spoke to his academic interests – in his history degree he looked at marginal perspectives and protest culture. Then there was its wide-ranging appeal. “The opportunity to reach out to people and bring more diverse audiences into the archive… well, the DrugScope material is a very good hook for that.”

Could it help realise his passion for breaking down barriers to archives? He thinks so, citing how it speaks to people across different disciplines, from drama to art to design. More than that, Day would love to attract people who have no experience with archives at all. “There’s so much in the collection that isn’t necessarily academic and can be enjoyed in a non-academic way.”

His own experience of coming to academia slightly later in life has given him a clue as to how to make that happen. Although he didn’t become an archivist until his 30s – after an access course at 31, followed by a history degree and the necessary training before joining Wellcome – he had a lifelong interest in collecting. But when he scrolled archives online, he found “everything was just a dead end”.

People with jobs like his have the power to change this, he says. “It’s important as an archivist to articulate what some of that stuff is and why it’s interesting.” And, most crucially, he says, “just that it’s there”.