Her freezer full of breastmilk her baby didn’t need, Alev Scott had to work out what to do with it. She wanted to help other babies, and donating her stores to a hospital milk bank was perhaps the obvious choice, but some women give their milk directly to other parents or sell it to pharmaceutical-style companies. Here Alev explores all three options.

Sharing breastmilk with parents

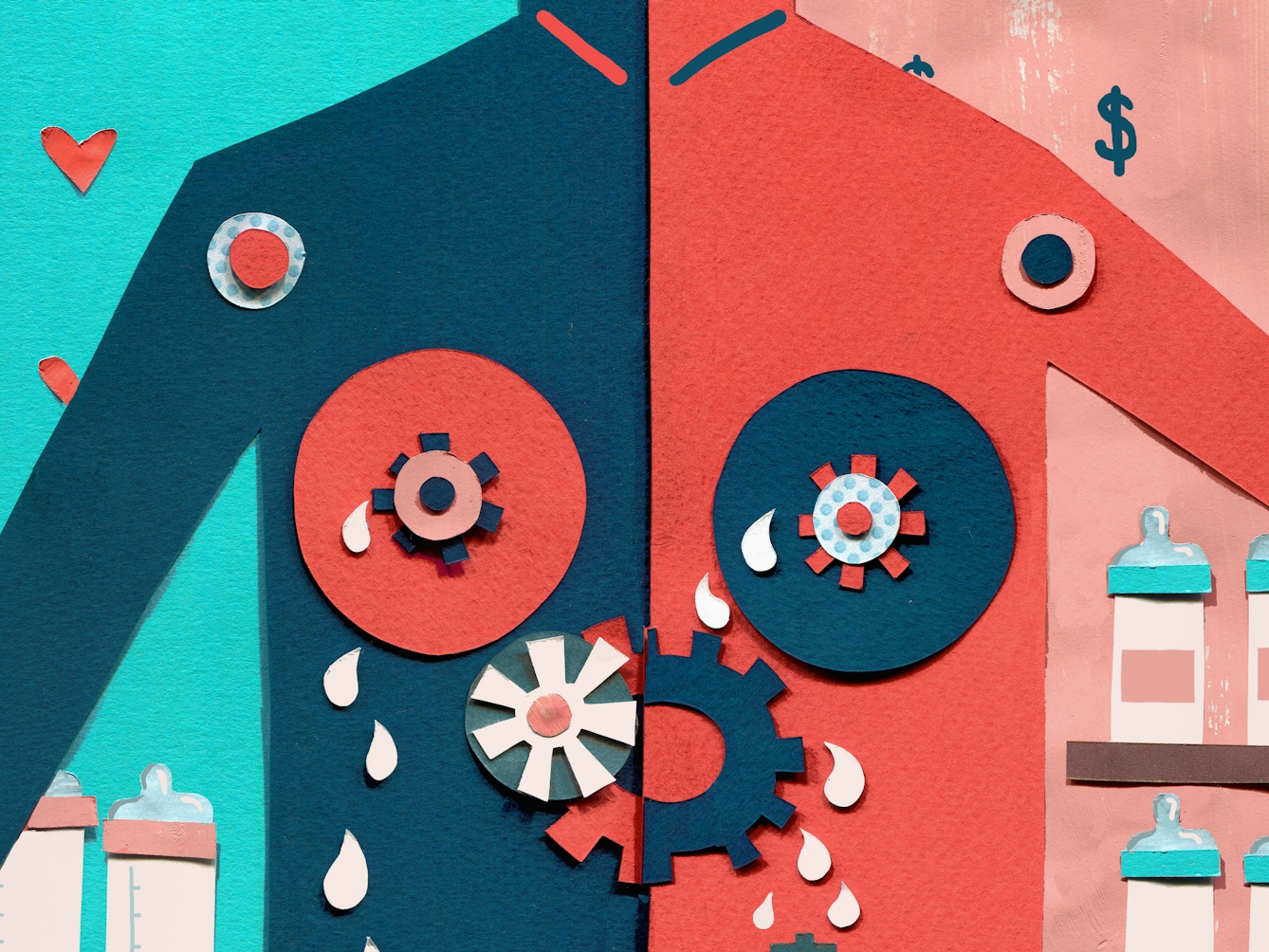

Words by Alev Scottartwork by Vicky Scottaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

One sunny morning in 2021, about six months after I gave birth, I opened my front door to a stranger and handed her a large cooler bag of frozen breastmilk. There were four litres inside, packaged into little plastic sachets. I remember feeling lighter, unburdened.

To get here, I’d had my blood tested for HIV, syphilis, hepatitis and HTLV (a virus that causes a type of cancer), filled out various forms, promised not to take any drugs (including ibuprofen), and committed to handing over at least three litres by this date.

My clinical odyssey would soon be over – the breastmilk unfrozen, screened for pathogens, pasteurised and then distributed by the milk bank at Bristol’s Southmead Hospital. I had a surreal thought: I’d never done jury service, but my breasts had done their civic duty.

Expressing human milk efficiently has only been possible since the invention of the electric breast pump, the terrifying machine I first encountered a few days after I gave birth. Once I’d mastered it, I found it much more effective than a manual pump.

Crude breast pumps in ancient times used water to create to a weak vacuum, while prototypes for commercial sale, relying on hand-operated bellows, were patented in the mid-19th century. But it was not until 1991, when the Swiss company Medela launched an electric pump for home use, that mothers could easily collect their own milk.

Breastmilk had been transformed into an easily transportable commodity, without producer and consumer ever needing to meet.

Other companies followed and, thanks to the internet and modern standards of refrigeration and freezing, the donation and sale of breastmilk to strangers far and wide became possible. Within a few decades, breastmilk had been transformed into an easily transportable commodity, without producer and consumer ever needing to meet.

“Expressing human milk efficiently has only been possible since the invention of the electric breast pump, the terrifying machine I first encountered a few days after I gave birth.”

The milk I donated to Southmead Hospital would likely go to premature, low-weight or “medically fragile” babies whose mothers were ill or yet to establish their own milk supply. Breastmilk is considered important for these babies as it is easier to digest than infant formula; it can also help develop brain and neurological tissue, and prevent intestinal infections.

Unlike in the UK, where local NHS hospitals process donations alongside not-for-profit organisations, in the US there are relatively few non-profit milk banks. This became painfully apparent during an infant-formula crisis in 2022, caused by a major factory closing down amid concerns over contaminated products. The closure led to supply issues and a months-long, nationwide shortage. Mothers stepped up: milk banks reported an increase in extra donations to cope with higher demand.

Informal parent networks

New parents can find themselves in stressful situations where they don’t have what their baby needs, be it formula or breastmilk, and so they explore other options. In Amsterdam, shortly after I gave birth, I learned from a local WhatsApp group that informal breastmilk donation is not uncommon among friends and acquaintances – via word of mouth, or online groups that facilitate sharing.

Ana, a first-time mum, gave birth around the same time I did in 2021. She didn’t produce any milk for ten days, something a midwife told her might have been due to gestational diabetes. Ana explained to me that she had experienced the same kind of over-anxiety I had during the early postpartum days, recoiling at the idea of formula:

“At the beginning, I was super-frustrated because I couldn't produce milk. I was crying and feeling like I wasn't like a mother. For me, formula was kind of a poison, it was not natural. I think my hormones were working against me!”

Ana found another mother willing to give her enough frozen milk for two weeks. She says, at first, she and her husband were nervous about accepting the offer – “In Amsterdam a lot of people smoke weed, so you never know!” But ultimately, “I didn't feel bad about giving my baby another mother's milk – I felt relieved.”

“Mothers stepped up: milk banks reported an increase in extra donations to cope with higher demand.”

I asked Ana whether she would have been prepared to buy breastmilk if she hadn’t found a donor. “In 2021 I was without work at all: financially we couldn't afford this at that time – even formula was expensive.”

Human milk at champagne prices

Ana is right – human milk is expensive. NeoKare Nutrition, a UK-based business that styles itself like a pharmaceutical company, launched in 2019, selling frozen breastmilk and its derivatives for prices that exceeded those of high-end champagne.

In 2022, NeoKare was charging customers £45 for 300 ml of breastmilk, which is roughly £150 per litre. In contrast, the company was paying lactating mothers £17 per litre. The transaction between mother and company was described as a “donation” rather than a sale. The strapline on the NeoKare website – “Become a Milk Provider, Save a Life” – implied that donated milk would go to babies in dire need, rather than to the general punter.

When I contacted the company in November 2021, NeoKare confirmed that “our milk is on sale to the public, but this can include prem[ature] babies and the parents source the milk to give to the baby in hospital”. In other words, their customers could include parents whose babies are entitled to be fed in an NHS hospital, for free, with milk from unpaid donors – if there are sufficient stores.

In January 2023, the Food Standards Agency announced it was working with Trading Standards to investigate how a small number of human breastmilk products made by NeoKare contained elevated levels of lead. All NeoKare’s products were recalled, and the company has now removed its prices from its website.

Prolacta Bioscience is a significantly more established commercial breastmilk business based in the US, which sells exclusively to hospitals – over 400 currently – and has recently initiated commercial activities in Europe.

“In 2022, NeoKare was charging customers £45 for 300 ml of breastmilk, which is roughly £150 per litre.”

A company representative explained to me that Prolacta offers “donors” $1.10 per ounce for their milk, and that there is currently a waiting list for anyone new who wants to donate. Prolacta uses these donations to produce a “human milk-based fortifier”, which is a “concentrated breastmilk that is added to mother’s own breast milk or donor milk”. This fortifier is given to premature babies in neonatal intensive care units at an average cost of $120 per day.

Fortifying breastmilk with extra nutrients is considered important for babies with very low birth weights (less than 1.8 kg), but it’s unclear if there are any medical benefits from fortifiers being derived from human milk.

Buying milk online

The commercial exchange of breastmilk is happening informally, too, on online marketplaces including Only The Breast and Facebook Marketplace. In these online spaces, lactating women can often sell for more than they would be compensated for donating, and buyers can pay a lot less.

Only The Breast seems to primarily serve the US and, to a lesser extent, the UK. You can place an ad as a seller or buyer, and the going rate is between £1 and £2 per ounce/30 ml, or around £45 per litre for milk. The price varies according to whether the buyer wants to buy in bulk, frozen or fresh, and what attributes they consider to be valuable. I’ve seen adverts where sellers demand higher prices because they are young or vegan, or because they have Covid antibodies.

The downside for the buyer, of course, is that the milk is unlikely to have been screened for disease or contamination. It’s worth noting that neither the Food Standards Authority in the UK nor the Food and Drug Administration in the US endorse the sale of breastmilk on the open market, and both have advised against buying online.

All breastmilk is bought on trust. Anyone can buy, for any purpose. I decided to find out who, and why.

Some names have been changed.

About the contributors

Alev Scott

Alev Scott is a journalist and author. Previously based in Istanbul and Athens, she has written about politics and culture in the Mediterranean region for the Financial Times, the Guardian, Harper’s Magazine and Newsweek, among others. Her books are ‘Turkish Awakening’, ‘Ottoman Odyssey’ and ‘Power and the People’.

Vicky Scott

Vicky Scott is a Sheffield-based freelance illustrator who specialises in creating colourful and eye-catching mixed-media collages. Her work is inspired by Art Deco, 1960s psychedelia, mid-20th-century travel posters, and the natural world. To date, she has been commissioned to illustrate for a diverse range of clients including Microsoft, Cheltenham Festivals, the Postal Museum, Waitrose and the RSPB.