What does it mean to be home? Tanya Perdikou felt like an outcast growing up in an ex-commune in rural Norfolk. Having moved from the country to the city, and from Europe to Asia, she’s learned that feeling as though you belong in a place is much more complex than it seems.

Searching for a place to call home

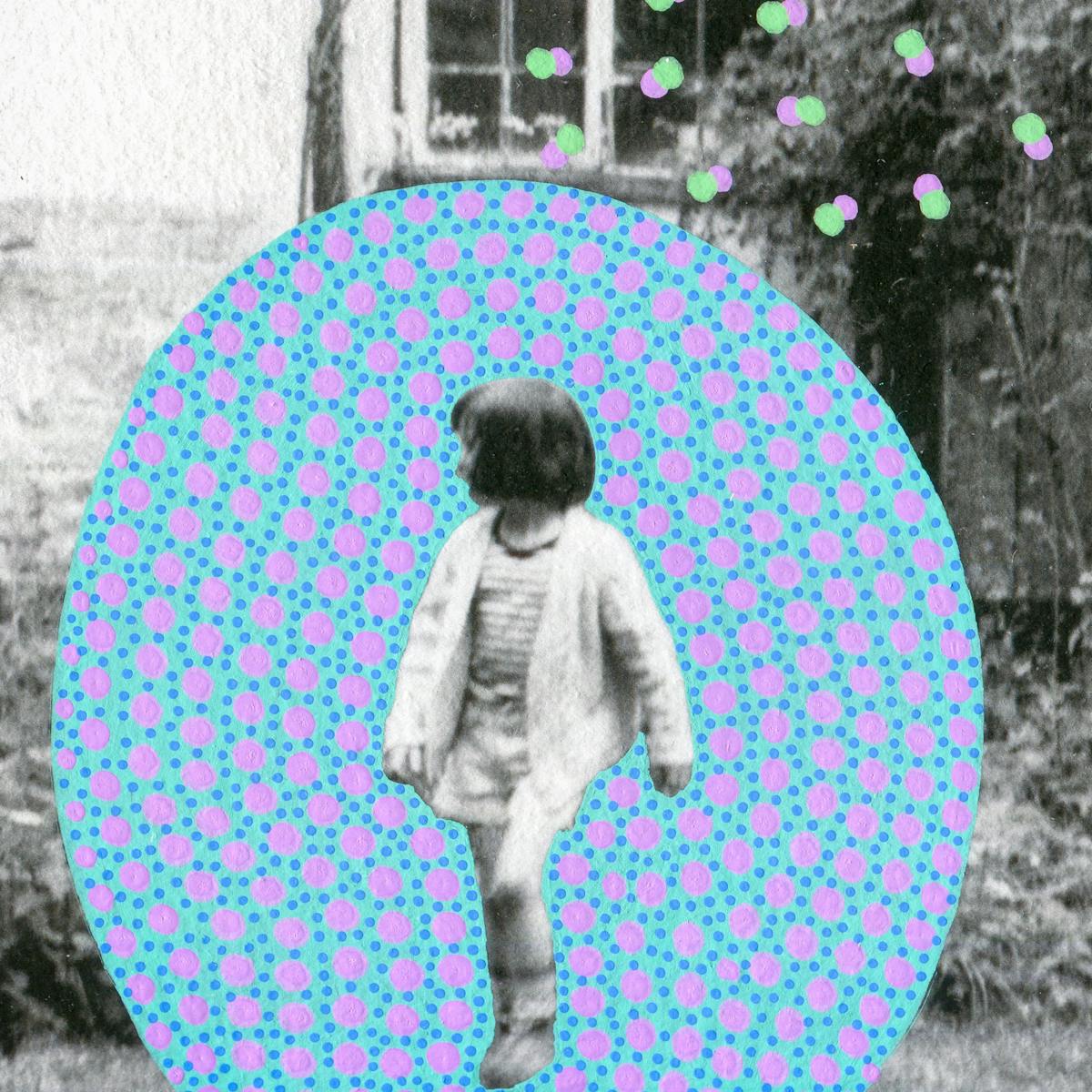

Words by Tanya Perdikouartwork by Naomi Vonaaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

As I search for a sense of belonging, I am discovering how tied up that feeling is with my grandma and her unconventional life. For her, feeling like she didn’t fit anywhere, that she was unwanted, led to alcohol addiction. Her recovery was connected to finding a community where she felt that she did belong.

In the 20 years since I left Norfolk, I’ve never been in one place for longer than five years. It is dawning on me that these shifts from place to place might be connected to my search for belonging – and that perhaps no single location can satisfy that.

My complex relationship with place can be traced back to Grandma’s decision to buy an old rectory in a conservative Norfolk community and turn it into a commune. This was the setting for a childhood of adventure but also of feeling like an outsider.

When we were at the rectory, my siblings and I built dens and ran wild in acres of garden, woodlands and fields beyond. Mice crept out of our bedroom cupboards at night, and weekends were spent gathering around the kitchen table with our huge extended family, talking about life, politics and music.

Among the wider rural Norfolk community, we were anomalies. It was a place to conform or face ridicule, verbal or even physical abuse. I got called a “dirty fucking gipsy” by the boy up the road and we faced racism in various different guises. I put on a show for friends’ parents, avoiding any mention of my absentee, drug-addict father.

This is why I feel a yearning whenever I hear John Denver croon, “Country roads, take me home/To the place belong.” I don’t yearn for home, but for the simplicity of knowing where the place I belong is.

“My complex relationship with place can be traced back to Grandma’s decision to buy an old rectory in Norfolk and turn it into a commune. This was the setting for a childhood of adventure but also of feeling like an outsider.”

A feeling of unreality

London has come closest to satisfying my need to experience difference in my day-to-day life, but six years ago the urge pushed me even further, to chaotic and beguiling Bangkok. My first few weeks in Thailand felt exciting and fresh, but a month after arriving I discovered I needed an operation under general anaesthetic.

The process of diagnosis was traumatic (it involved being told in broken English I had a “large lump” beside my ovary), and then I faced my first-ever hospital stay thousands of miles from most of my friends and family.

I initially made a quick recovery. But a couple of months later something seemed to malfunction. I felt disoriented, as if I was floating outside of my body or seeing everything through a pane of glass. I would experience numbness down one side of my face. My energy would crash. I would walk the streets of Bangkok but feel like I wasn’t really there.

I felt disoriented, as if I was floating outside of my body or seeing everything through a pane of glass.

I didn’t feel ‘normal’ again until I’d taken an extended holiday back in the UK. Being in a place I understood, around people I had long-standing connections with, somehow allowed me to recalibrate.

But when I moved back to the UK for good after four years in Thailand, I experienced the same disorientation I’d felt when I’d first emigrated. Facial numbness, the extreme lethargy, the feeling of disconnection and unreality plagued me on and off for months once I was back in London.

“Being in a place I understood, around people I had long-standing connections with, somehow allowed me to recalibrate.”

The science of place and person

Studying the relationship between person and place has helped me make sense of my experience of emigrating. Place isn’t simply a static collection of physical features. According to the People, Place and Space Reader, “the environment informs human knowledge, and human experiences shape the way by which the environment is known”.

The geographer Doreen Massey goes further. In reference to globalisation and technological advances, she writes that places should be “imagined as articulated moments in networks of social relations and understandings”.

I had naively relocated to a new place and expected it to become ‘home’. But the experiences I had in Bangkok were initially frightening and negative. For it to be home I had to have a sense of its networks and my place within them. Instead I’d arrived and been catapulted straight into its health system alone.

In ‘Invisible Cities’ Italo Calvino writes, “Arriving at each new city, the traveller finds again a past of his that he did not know he had: the foreignness of what you no longer are or no longer possess lies in wait for you in foreign, unpossessed places.”

I underestimated what it means to sever the connections with familiar places and people and strike out anew. And then, when I returned to London a few years later, my “social relations and understandings” had moved on again. I became locked in another struggle with disconnection. I was so tired and spent, and I felt like a different person, having become a mother while I was away.

“I underestimated what it means to sever the connections with familiar places and people and strike out anew.”

The solace of the natural world

In a report stressing the power of nature to integrate immigrants and people of colour who feel marginalised in British society, the Black Environment Network places emphasis on the power of natural features to provide continuity between ‘home’ and an alien environment: “…this continuity enables an emotional homecoming,” it says.

“Grass can always be recognised as grass, trees are trees, no matter how different. Greenness puts us in touch with a vibrant sense of growing things, and of being cradled by the earth.”

Which leads me back to Grandma, and how, in the places she felt at peace, I feel at peace. She was the kindling that lit up my love of wildlife. In doing that, she’s given me the ability to find solace when I’m navigating unfamiliar territory. Even if it couldn’t heal the disconnection I felt in Thailand, nature did provide snatches of comfort, like when bulbuls nested on our balcony and I was so taken with them, they almost felt like family.

And later, when the coronavirus pandemic struck and there were days when I woke up with a blackness in me, I’d go out onto the concrete porch of my London flat, see the first of my daffodil bulbs poking through in the raised bed, and smile.

“Dear Tanya,” Grandma has written on a slip of paper tucked into a copy of Roger Deakin’s ‘Notes from Walnut Tree Farm’. “This is the kind of book one can pick up at any time – for even a few moments – and feel part of the world in which we live.”

She’s marked a passage on page 137: “Grandpa Wood – cracking open the coal to show me fossil ferns, the concealed history of the carboniferous forest. Trees make time stand still.”

Wherever I go in the world, there will always be trees. I can go to them, and cheat time by being with Grandma again. Each encounter a homecoming.

About the contributors

Tanya Perdikou

Tanya Perdikou is a freelance writer. She specialises in telling stories of how the human experience intersects with society, nature and travel. Among others, her work has been published by the BBC, the Huffington Post, the Guardian and the Bangkok Post.

Naomi Vona

Naomi is an Italian artist based in London. She defines herself as an “archival parasite with no bad intentions”. Her works combine photography, collage and illustration, and her research is focused on altering vintage and contemporary found images, creating a new interpretation of the original shots. Using pens, paper, washi tape and stickers, she gives every image new life. Her work is basically composed of three elements: her background, inspirations and subconscious, which are also the glue that pulls everything together.