India is one of the world’s largest producers of dairy. Milk’s ascension in the country is a result of postcolonial notions of progress, globalised industrialisation and nationalist nutrition guidance.

Sacred cows and nutritional purity in India

Words by Apoorva Sripathiartwork by Cat O’Neilaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Article

Just as cultures transform milk, so milk (re)shapes cultures.

Dairy consumption in India can be traced as far back as the Indus Valley Civilisation (3300–1300 BCE), where it was an essential part of the diet. Elsewhere in the world, humans first started consuming milk around 7,400 years ago, during the Neolithic period, when agriculture, and domestication of animals, plants and crops emerged.

Even if the story of dairy goes back millennia, our ability to digest it starts with mother’s milk. Infant digestive systems secrete lactase, the enzyme required to break down the lactose present in milk. After weaning, lactase production usually plummets, and eventually stops. Lactose intolerance is therefore common among most adults. Only a third of humans have evolved to digest milk and most have Northern European ancestry, in which a certain genetic mutation results in high lactase persistence.

India’s dairy culture is far-reaching even if lactase persistence is low: the uses, traditions, and history of yoghurt in India are wide-ranging, finding mentions in traditional Indian Ayurvedic medicine, the early 12th-century Sanskrit text ‘Manasollasa’, and early Tamil literature. Ghee (made from clarified butter or yoghurt) too has been consumed for centuries, and is considered an important fat in cooking, ritual and medicine.

Notably, both yoghurt and ghee have low lactose content, as they are made from fermented dairy. Today’s commercially processed cheese, though popular at street-food stalls, is comparatively new within India’s dairy history, probably due to taboos attached to rennet, an animal product used in the manufacturing process.

Milk for progress

It was in colonial India that drinking cow’s milk became considered “life-giving”, according to historian William Gould in his 2004 book ‘Hindu Nationalism and the Language of Politics in Late Colonial India’, associating the bovine beverage with the strength of the nation. Following India’s independence in 1947, a contemporary nationalist project developed to promote milk consumption as a ‘pure’ health food: milk was instrumental in not only building individual bodies, families and culture, but also in establishing a nation-state.

“The history of yoghurt in India are wide-ranging, finding mentions in traditional Indian Ayurvedic medicine, the early 12th-century Sanskrit text ‘Manasollasa’, and early Tamil literature.”

In the 1950s and 60s, India had to import milk to feed its growing population. It wasn’t until the 1970s that milk production in India expanded exponentially. In 2021–22, India contributed almost a quarter of the global milk production.

India’s robust milk production developed as a result of Operation Flood, a dairy development scheme where milk surpluses (as milk powder) from the United States and Europe were routed through the World Food Programme (WFP) to India. Initiated in 1970, Operation Flood saw the transformation of India into the world’s largest milk producer by 1998, earning the programme the nickname ‘White Revolution’. The legacy of Operation Flood unfolded in various ways, and, importantly, dairying within the country became a measure of national progress.

Milk, then, finds a special place in India, not just as food but as ambrosia itself.

Initially, the aim of this food aid was to reduce prices and boost milk supply in India. But the chairman of the Indian National Dairy Development Board (NDDB), Dr Verghese Kurien, had other plans. He persuaded the WFP to allow his milk producers’ union in Gujarat to reconstitute the powder, sell the milk, and invest the profits in the expansion of the country’s dairy industry.

While this was intended to bring commerce into rural communities, in reality “farmers were depriving their own undernourished children of cows’ milk to sell to the cooperatives”, according to American activist Greta Gaard. Milk as a subsistence economy changed into commercial industry, ignoring the needs of rural populations and, especially, women. More milk was available, but not everyone could afford it.

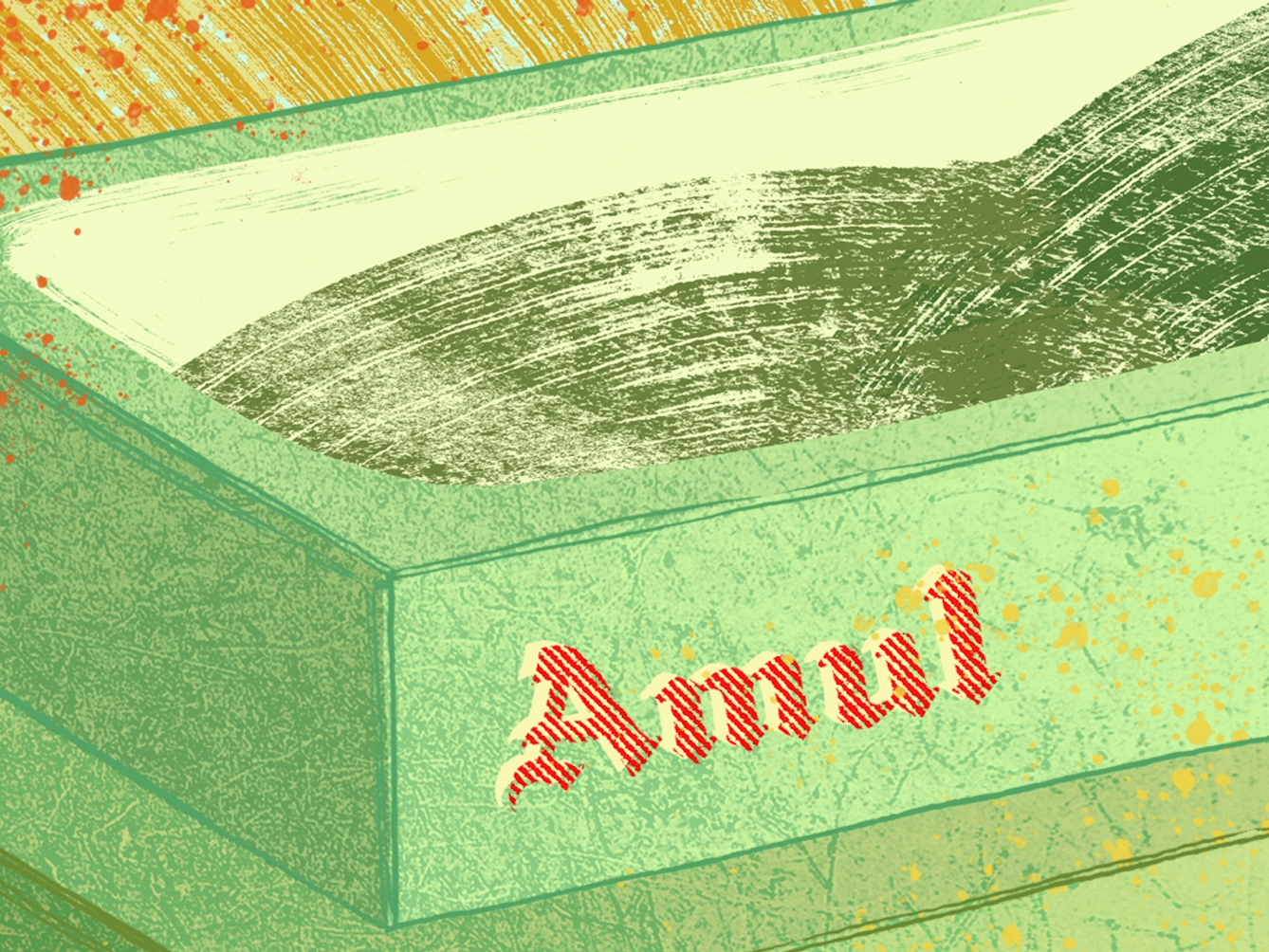

To make the excess milk palatable to the masses, the Indian dairy cooperative Amul marketed it against a slew of foreign colas that entered the country on the back of its economic liberalisation. The result was an advertisement that went, “Amul doodh hai wonderful” (Amul milk is wonderful): it proclaimed that milk was an all-season drink, interspersed with visuals of people enjoying themselves drinking milk. It was a memorable campaign in the 90s, and Amul extended this campaign of ‘goodness’ to its other products, including cheese, ice cream (“real milk, real ice cream”) and butter.

‘Pure’ milk

The notion of milk as ‘pure’ and inherently good results from its ‘natural’ provenance and a belief that it is essential to the human diet. In places like the US and UK, this had a lot to do with 19th-century innovations in refrigeration, transport, pasteurisation, and, more importantly, the interests of newly industrialised farming practices that supplied milk to booming urban centres, setting in motion a commercial dairy industry.

“It wasn’t until the 1970s that milk production in India expanded exponentially. In 2021–22, India contributed almost a quarter of the global milk production.”

The commercialisation of milk transformed the way Indians consumed it. As Andrea Wiley notes in her 2014 book ‘Cultures of Milk’, the “Indian dairy industry was targeted for expansion using donations” via the WFP as surplus milk production in the West threatened to destabilise local milk prices and collapse dairy industries.

What also looms large is a Western imposition of milk as the solution to undernutrition and poor physical development, especially for a developing country that reports high malnutrition but low levels of access to quality food and a rise in milk prices.

Nutritional science elaborated in a Western context routinely prioritises milk’s “biological role” in sustenance. It was often touted as a superfood containing enough calcium, protein and vitamin D to help grow bones and keep them strong. The West promoted milk as a ‘pure’ health food to keep up with abundant milk production, while nutritional science that prioritised Western bodies provided the evidence.

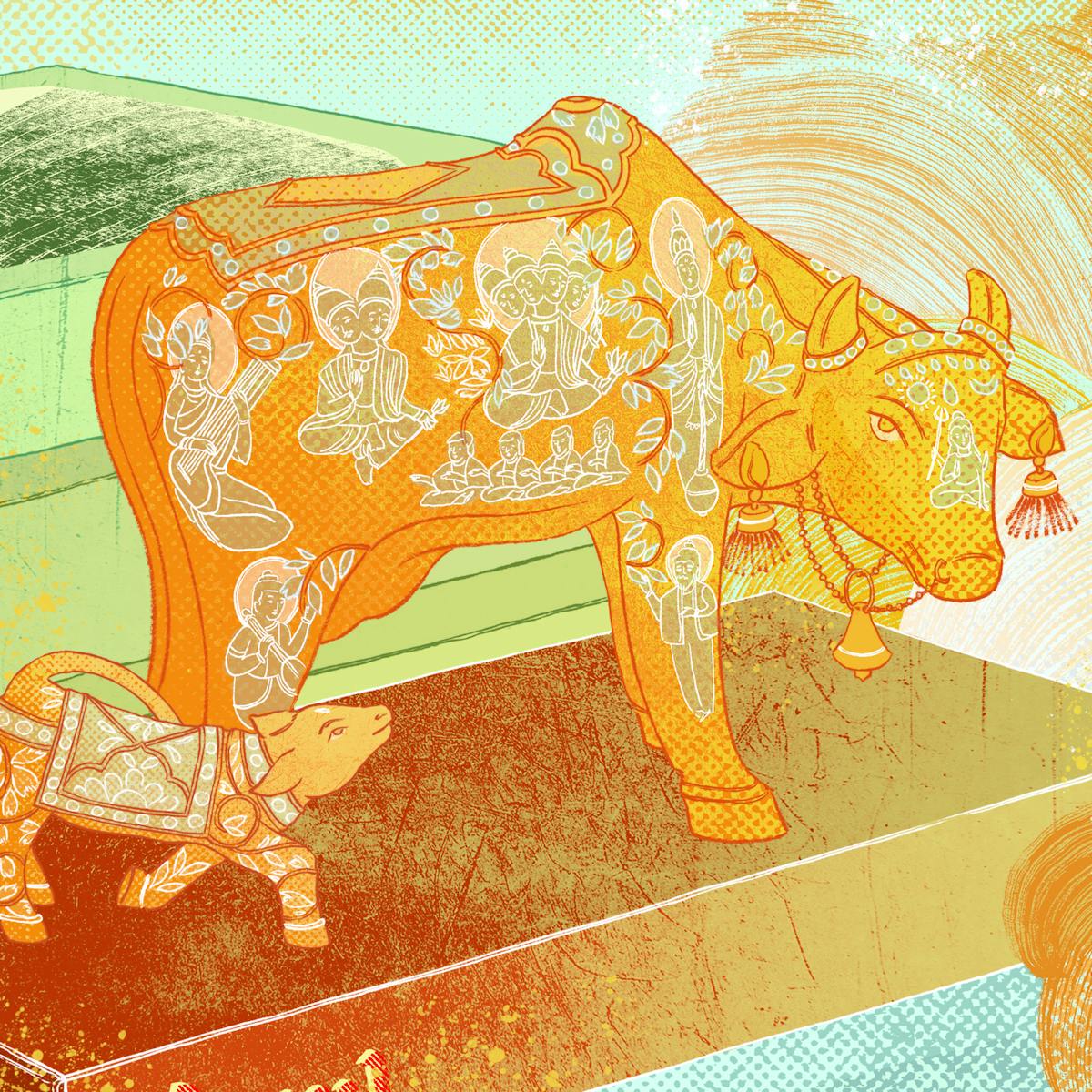

In India, milk is also considered ‘pure’, in part due to tenets in Hinduism – it comes from the cow, which venerated as sustaining, primaeval and sacred. Traditionally, however, most milk in India is from buffalo, which is equally valued for meat, and its efficient use as a draught animal. Nevertheless, it is the cow, not the buffalo, that’s seen as a symbol of endless bounty in Hinduism.

In a society that’s largely governed by Hindu patriarchal laws, the cow is Kamadhenu, a divine mother goddess who protects and provides everything that’s desired. The Hindu god Krishna, well known for his love for cows and milk products, also contributes to the myth of the holy cow and milk as ‘pure’.

Milk for an imagined future

Milk, then, finds a special place in India, not just as food but as ambrosia itself.

At the heart of the notion that milk is essential to the country lies a substantial dairy tradition that’s deeply embedded in Indian society and culture. Both ghee and yoghurt remain much loved because of their many uses, ease of storage, and taste.

“In a society that’s largely governed by Hindu patriarchal laws, the cow is Kamadhenu, a divine mother goddess who protects and provides everything that’s desired.”

The Hindu patriarchy that considers milk to be virtuous and wholesome doesn’t extend the same courtesy to beef or eggs, which are seen as impure, unclean and taboo. Eggs, which offer more nutrition than milk, are easier to transport and equally ‘natural’, but constantly face opposition from Hindu religious groups and some state governments for being included in school and anganwadi (rural childcare centres) lunches, along with meat, onions and garlic.

This notion of egg as ’non-vegetarian’ and milk as ‘vegetarian’ (even though it derives from an animal) exists only because of Hindu Brahminical ideas about the ‘purity’ of food, when nutrition should be the focus. The same caste purity paints India as a vegetarian nation, making meat morally problematic.

Milk is privileged in religious and cultural discourses, in its role in child development and even pop culture. It is routinely poured on actors’ cut-outs prior to movie releases in Tamil Nadu, replicating the Hindu religious practice of pouring milk on idols. Milk processed into industrial cheese seems boundless in street food, added to everything from dosa and parathas to loaded sandwiches, and ice-cream chaat.

There’s no doubt that milk has shaped Indian culture in many ways – religious, political, economic – and has served as a measure of progress. Milk also occupies a special place in the food hierarchy. But it cannot be so heavily depended upon to fulfil the nutritional needs of this developing country, especially if it is unaffordable and nutritionally inadequate. Milk cannot truly be a symbol of progress if its popularity only seeks to enforce Hindu casteist ideologies and fails to fortify the many bodies that make up the nation.

About the contributors

Apoorva Sripathi

Apoorva Sripathi is a writer, editor, and the co-founder of the independent magazine CHEESE. She also runs shelf offering, a food and culture newsletter.

Cat O’Neil

Cat O’Neil is an award-winning freelance illustrator, specialising in editorial. She studied at the Edinburgh College of Art, graduating in 2011, and has lived in Hong Kong, London, Glasgow, Lyon and Edinburgh. Her clients include the New York Times, Washington Post, WIRED, LA Times, Scientific American, the Financial Times, the Guardian/Observer, Libération and more. Her work explores the use of visual metaphors to convey concept and narrative, and combines the use of traditional and digital mediums. Much of her recent work includes the creation of 3D paper sculptures, which are made in her studio in Edinburgh.