Chris Miller gives an unsentimental account of how he learned to live with the physical and psychological changes resulting from a brain injury, and discovered a new sense of self in the process.

About 30 years ago I went to my doctor with tinnitus – ringing in one ear. After several tests, a non-cancerous growth on my acoustic nerve was found, called an acoustic neuroma. I had an operation to remove it, which involved drilling a hole in my skull. The neuroma was removed, but my sense of balance was all over the place for three months and I permanently lost the hearing in one ear. Apart from these, I was fine.

More than 20 years later my balance problems had returned and I went to see my doctor again. Initially she diagnosed an ear infection, but when I told her my history, she said that I needed to have an MRI scan. It found that the acoustic neuroma had come back, there was a cyst growing, and I would need another operation to remove it, otherwise it would grow and affect the rest of my brain.

When I awoke from this second operation, I had stroke-like symptoms. The whole right side of my body – my walking, my writing (I am right-handed), face, eye and speech – was badly affected, and still is. When people ask me about what has happened to me, rather than going into the complicated details of my medical history, my shorthand explanation is that I had a stroke.

“Overnight it was as if my whole identity had changed. I was a different person with a different face.”

Accepting my new self

Before my surgery I could effortlessly leap up the stairs two at a time without thinking. After my ‘stroke’ it took fifteen minutes of intense concentration and effort to do the same thing. I also had to slowly relearn how to do a myriad of other physical activities – like writing, walking and tying my shoelaces.

Overnight it was as if my whole identity had changed. I was a different person with a different face. Initially I tried to go back, to recover the old me, the body I had before, but soon realised that only very small improvements were possible. To aim at the recovery of my old self was a fruitless and frustrating task. Instead, I had to come to terms with the limitations of my changed body and accept my new self.

As well as having a physical impact, my brain injury had an impact on how I saw myself. Overnight the role I performed in my family changed from that of a father to that of a dependent child. I found it hard to accept this sudden change, and coupled with my communication difficulties, this led to increased frustration and anger.

‘What do you think of the slide’ by Chris Miller.

Being accepted by others

There were difficulties too about whether I would be accepted in wider society. Someone in the street recoiled from me in horror when they saw my face. I wondered whether I would ever be accepted again in the wider world as a ‘normal’ human being.

Soon after this I just about managed to swim in a pool for the first time since my ‘stroke’. Afterwards a ten-year-old boy I didn't know came up and asked me whether I had been on the water slide yet. As politely as possible, I said no, I didn’t go on water slides, and we struck up a conversation about what I thought of the pool.

For the first time someone who was not a member of my family or a healthcare professional was speaking to me as a ‘normal’ human being. It seems trivial now, but at the time it was life-changing. I realised that how others responded to me – with fear or acceptance – was their issue, their problem, not mine. But the conversation with the boy showed I could be accepted as a fellow human being.

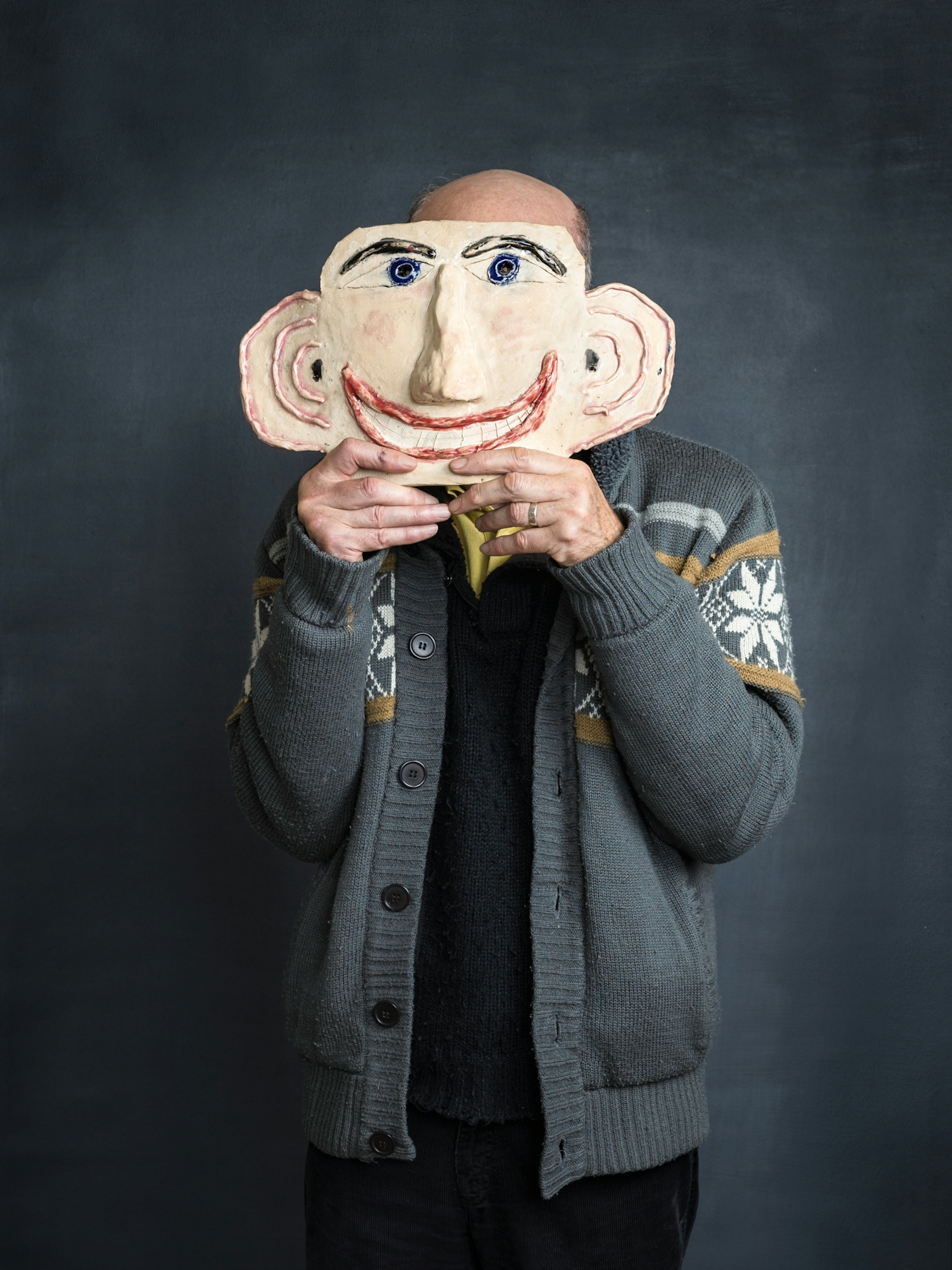

Chris Miller’s, ‘Me as...’ series

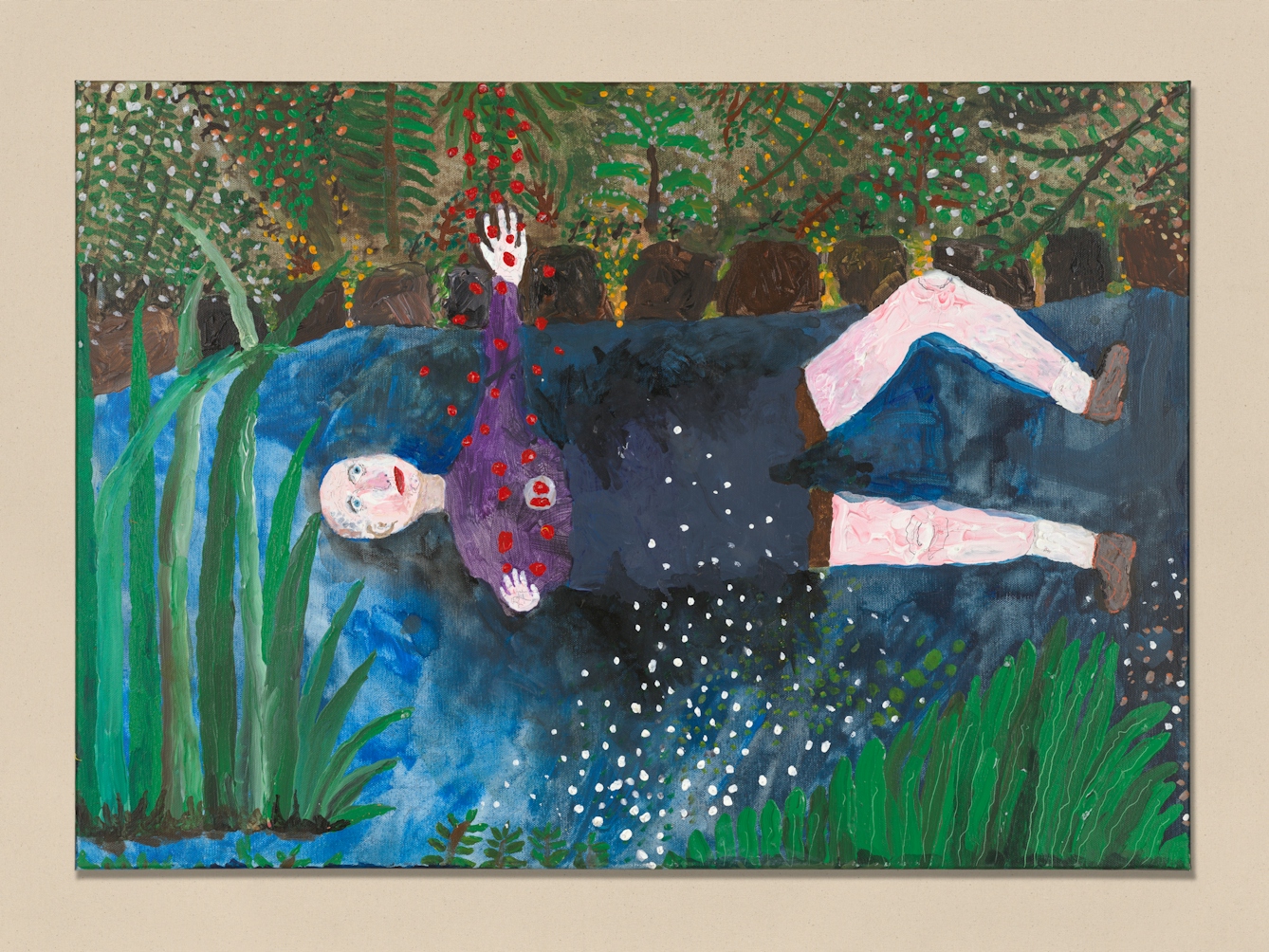

‘Me as Ophelia’ by Chris Miller.

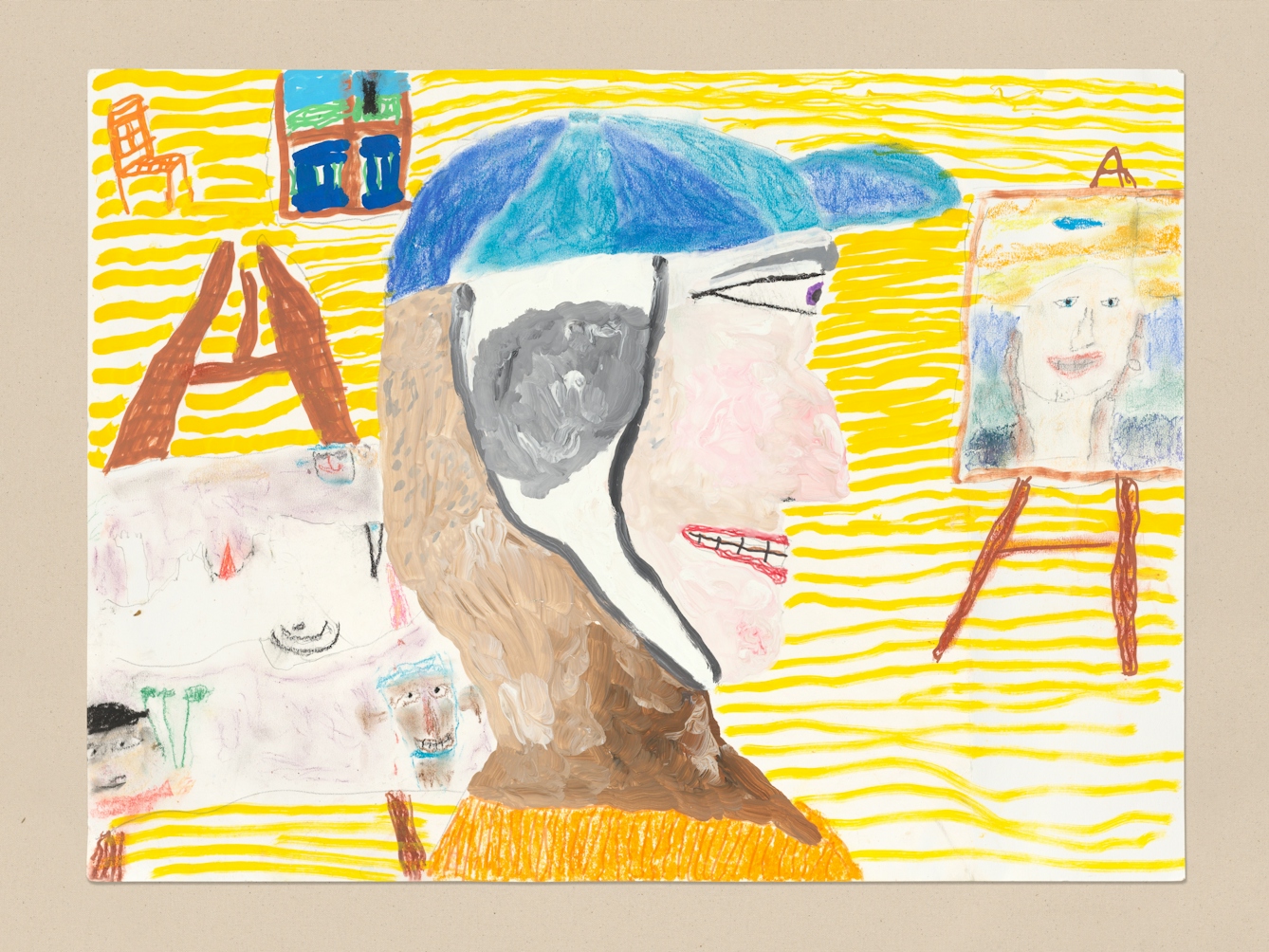

‘Me as Vincent van Gogh’ by Chris Miller.

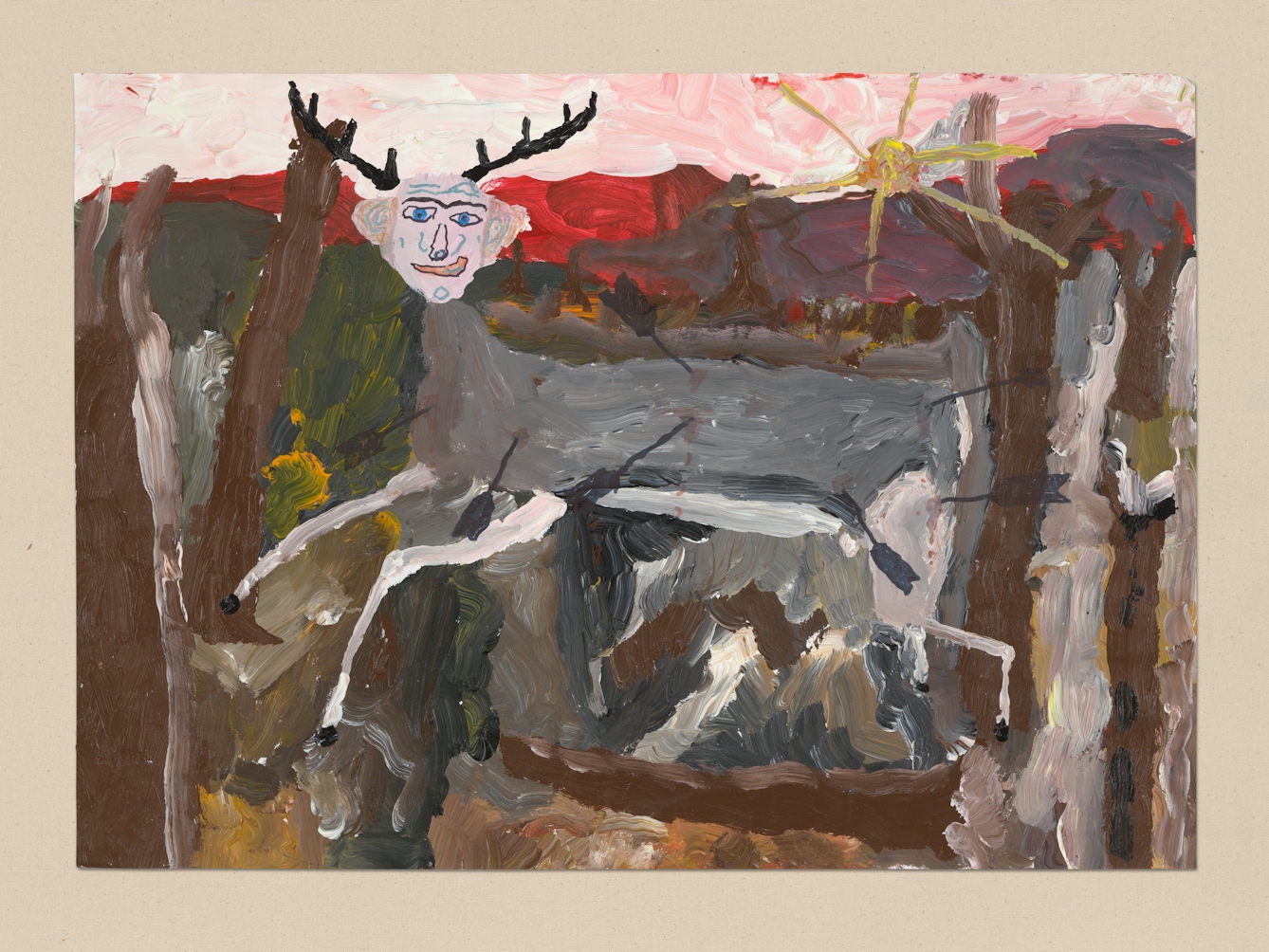

‘Me as the wounded deer’ by Chris Miller.

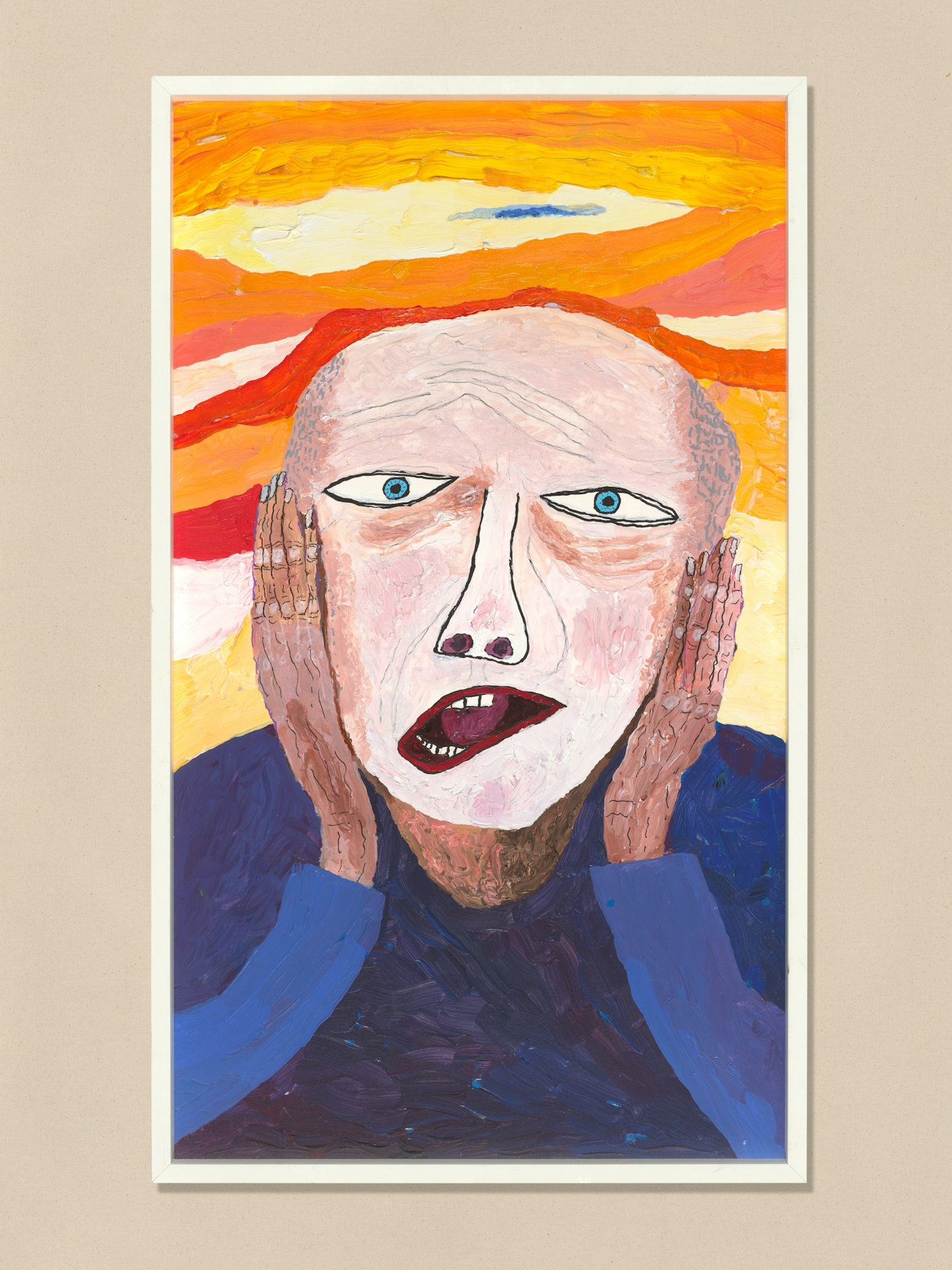

‘My Scream’ by Chris Miller.

‘The Good Hoodie’ by Chris Miller.

Tom Waits and me

About two months after the second operation my consultant sent me to have gamma rays fired at my head for two hours to make sure the acoustic neuroma did not return. While I was being zapped, I could choose music I to listen to, and I chose music by Tom Waits, a famously eccentric and dark singer-songwriter.

Unbeknown to me, the medical technician would have to listen as well. After two hours she told me she had had enough of listening to Waits – but not me – I loved it! And what mattered was my healing (not her musical taste).

For me, life after brain injury is a bit like Tom Waits’s music. Out of failure, dissonance, ugliness, grumpiness and downright horror – the most unpromising raw material – a beautiful diamond can be created that shines out even more brightly because of its dark, chaotic surroundings. In my life, in its best moments, and out of my illness, I have tried to stubbornly assert my right to make my own quirky choices, to reassert my identity, to be me.

About the contributors

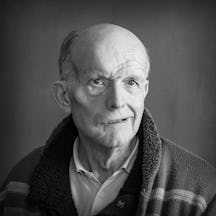

Chris Miller

Chris is a retired science teacher, and youth and community worker. In 2013 he had a brain operation to remove a cyst growing on his acoustic nerve. The operation left him with stoke-like symptoms in the form of weakness on one side of his body. Since then, largely through the efforts of the brain injury society Headway East London, Chris has returned to writing and started to make art.

Thomas S G Farnetti

Thomas is a London-based photographer working for Wellcome. He thrives when collaborating on projects and visual stories. He hails from Italy via the North East of England.