Walking down Railton Road is a stroll through memory for Jacqueline L Scott, who reflects on environment, race and its relations in London.

I was a country girl. Growing up in rural Essex in the 1980s, I rarely went to London then, and when I did, the trips were filled with excitement and fear, especially when heading into Brixton. In that small corner of the city, I met so many people who looked like me that I was shocked. I am Black. Walking around Brixton today brought back the sweet and sour memories of my village girlhood, and the glitter and gloom of my young adult life in the city.

Railton Road in Brixton is mostly residential, packed with 1930s-built beige-bricked or white-painted rowhouses. Front doors added a blink of colour: reds, blues and a few yellows. Ivy trailed from some of the pocket-sized front gardens. There were few trees to green the heavy-on-the-concrete street.

The narrow road was a chasm between two versions of life in London in the 1980s. It was called the frontline back then.

As I remembered it, on one side was Black life: jammed with Caribbean lilt and music, people working hard jobs, living in poor housing, suffering police harassment, and still dreaming that their children would have a better future.

143–145 Railton Road, 2022.

On the other side was white life: pickled people bewailing the decline of post-imperial Britain by scapegoating Caribbean immigrants, shouting in support of white supremacy at National Front marches, and ending a night at the pub with the ritual of chasing, beating or stabbing a Black man.

Ghosts of activists past

I started the walk at the top of Railton Road, near Herne Hill, and followed it all the way to its end: Brixton Market. A tight cluster of shops were near the start, including a café, convenience store and a dry-cleaner.

Stopping at 165 Railton Road, I looked about for the English Heritage blue plaque. The low-rise apartment block hugged the street corner; flats were above, and below these was the Brixton Advice Centre.

Blue plaques commemorate notable people such as writers, politicians and scientists. They celebrate who matters to the establishment – and so the majority are to dead white men. This blue plaque was an exception. Fixed on the top of the building it reads: “C L R James, 1901–1989, West Indian writer and political activist, lived and died here.”

165 Railton Road.

I met C L R James once, but my memory of the event is hazy. Back then, I was a community worker in south London, crisp from university, and still trying to figure out what it meant to be Black and British. After an event at the Brixton Advice Centre, I recollect walking up a narrow internal staircase to an apartment; the door opened and a wizened, white-haired man hovered in the background.

I was surprised that C L R James was so slim, short and old. I had studied his work in university. ‘The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L’Ouverture and the Haitian Revolution’ is a classic text on the Caribbean and its diaspora. For some reason I had expected the author of such a seminal book to be as large as his outsized reputation.

165 Railton Road was a crucial hub of Brixton’s Black community in the 1980s. It was the living room of activists, academics and community organisers. They met there to breathe, chat and laugh. And to plan strategies for dealing with the unexpected heaviness of life in the Mother Country.

They came there too, to organise demonstrations for those who did not survive a stabbing or a firebomb through the letterbox.

Maureen’s Brixton Kitchen, 52 Railton Road

The atmosphere around this part of the road shifts and the energy rises as you get closer to the Brixton Market end of the Railton Road. Maureen’s Brixton Kitchen serves as an introduction to Brixton and the neighbouring market areas.

“I’ve been cooking food for the best part of 20 years. I’m originally from St Thomas Parish, Jamaica. I started out when my son was two. My friends convinced me to start cooking, as I was reluctant at first because I never had the confidence to talk to people, to sell to them. I went to all the local hairdressers and asked if they would support me when I start, and they all said they would.” Maureen Tyne, owner of Maureen’s Brixton Kitchen.

“Everyone was very supportive. I would cook in the week, and on weekends I would walk around with my little book and collect the payments. I took a break again when I had my other son, but after some time I returned and it was like I had never left. People were waiting for my food. It made me feel so proud.” Maureen Tyne.

“I moved to this space and had my sister, sons, cousins, nephews and niece around helping me cook and deliver because it was so busy. It’s a family business supported by the community.” Maureen Tyne.

“Mum works hard, you know. But we all do our part, we support each other. At one point I was delivering food for Mum, but now I’m managing her social media account. Word of mouth has carried her so far for so long, but now we want to come stronger.” Kylan Matthews, Maureen’s son.

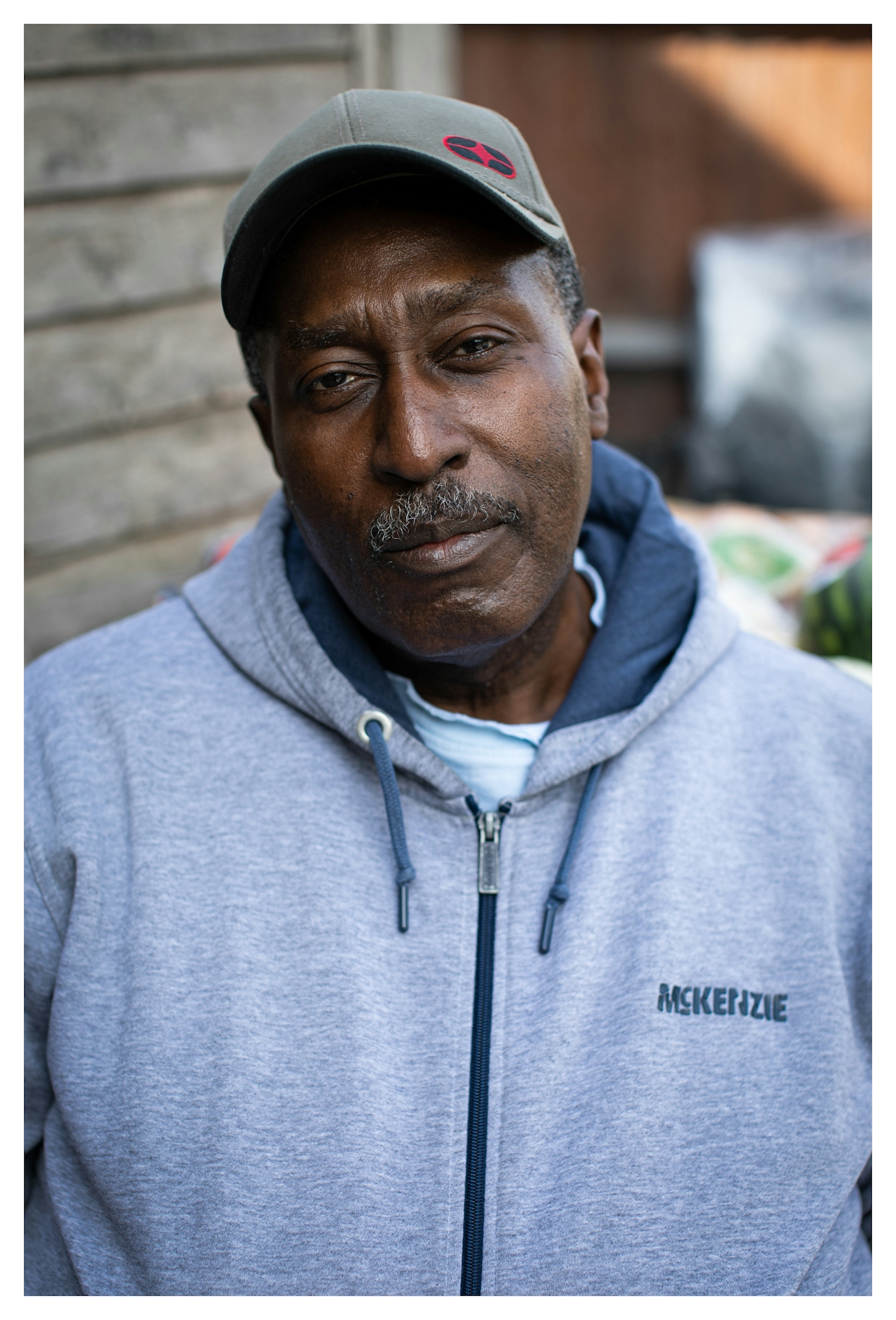

“I was here in the 1980s. I was here when there was houses all the way down this road and the community was alive. At those times, the police used to jump out on us for no reason. Teddy boys and racism. Police violence against us [Black people]. One day, coming from school, me and my friends were walking, and Teddy boys chase us down. I had to cut through some back roads to get home. They caught one of us, though, and they beat him up bad. Those times were rough.” Errol, kitchen support in Maureen’s Brixton Kitchen.

Parklife and politics

Leaving the ghosts of 165 Railton Road, I continued my stroll. There were few people out on the street on the winter weekday. It was damp and grey. Occasionally the clouds shifted and a patch of blue skies and golden sun flickered on the streets. Then they vanished, just like a fake promise.

I passed a splotch of green on my left. Spying through its surrounding fence, I saw an adventure playground, built out of tree trunks. It looked like fun, but no one was there. The wooden fence was like a giant hurdle; it was about four metres high. A pair of equally tall iron gates were attached to the fence. They were padlocked.

The distribution of urban trees follows a racial pattern – there are more in white areas, and fewer in Black areas... Racial inequality is mirrored in who has access to nature.

Green spaces reduce stress and improve the quality and length of life. There are six times as many parks in white areas of London compared to Black neighbourhoods. Trees clean the air, provide shade, and attract birds and butterflies. Street trees reconnect us to nature in the city.

37 Railton Road, 2022.

Trees also increase property values. The distribution of urban trees follows a racial pattern – there are more in white areas, and fewer in Black areas. Like Brixton. Racial inequality is mirrored in who has access to nature.

Near the park, a Black man and his hip-high daughter waited for the bus. He held her hand as she walked across a low concrete garden wall, turning it into a gymnastics beam. They were shut out of the green space, and the free and healing benefits of nature.

Rhythms and riots

Railton Road became livelier as I drew nearer to Brixton. More people and shops were on the street. Passing a music store that still sold vinyl records, I remembered popping into similar shops in the 1980s – filled with nerves and feeling like a fraud – to buy my first reggae albums.

I grew up in the countryside listening to rock music: Queen, Guns N’ Roses and Pink Floyd. In the shops I also got my first dub poetry records by Linton Kwesi Johnson. He lived on Railton Road and was a regular at number 165.

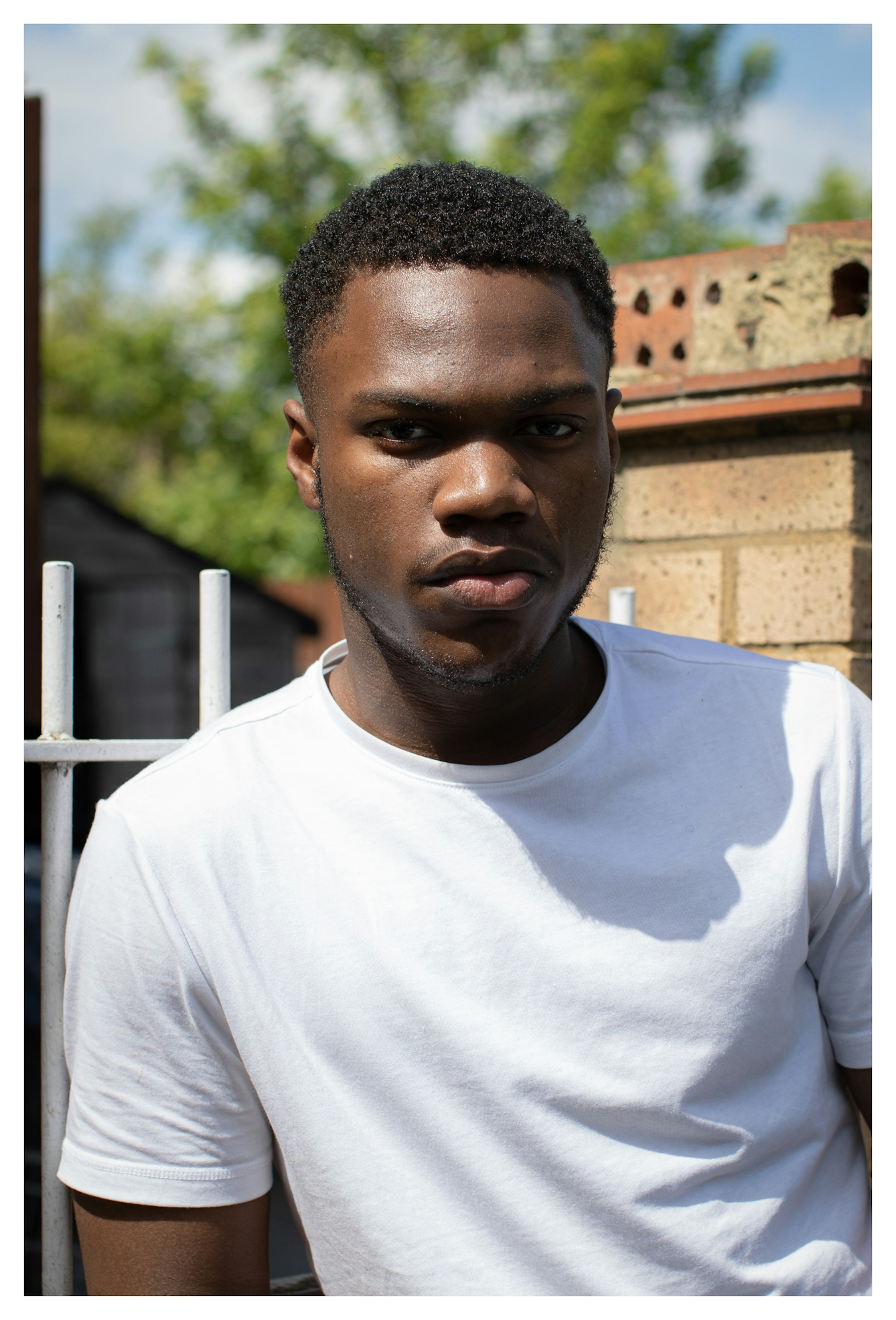

52 Railton Road, 2022.

I knew the words to Johnson’s ‘Five Nights of Bleeding’. The album was an omen of the simmering frustrations of the Black community. The ‘sus law’ produced these rumblings. The police used it to randomly stop and search young Black men, on suspicion that they might commit a crime. Every day, in any of the major cities in England, scores of Black men were frisked by the police.

The volcano erupted in the Brixton Riots of 1981. It was quickly followed by riots in other cities. It was Black British people’s declaration of resistance. It was the latest rebellion against slavery and its afterlife.

Skinheads in the countryside

I watched the riots on television. I grew up in another world – a small town, surrounded by farms, gossip, and post-World War II council-housing estates. There was little work in the rural Essex backwater. The only things thriving were the pubs, charity shops and hope.

Brixton Market, 2022.

Skinheads once waited for me outside the school gates. Still, I could not get my head around the Brixton Riots. In my small town I saw the police only a handful of times a year – usually sitting in their cars in the town centre or driving through the housing estate. In my mind, if the police stopped you, it was because they had reason to. The idea that you could be stopped and searched simply because you were Black made no sense.

It was only after I moved to London, and started as a community worker, that I began to understand police harassment.

It was later still that I realised that injustice takes many forms – like who gets the parks, ponds and trees in their ’hood, and who gets only concrete streets. Racism shapes who has access to nature in the city, and who feels welcome in the countryside. And it is for this reason that I research and advocate for equitable access to all of nature for Black people and other racialised groups.

At Brixton Market my ears picked out the new Black British sounds – Nigerian voices and music – as I searched for a café. Sipping tea and nibbling on biscuits, I mulled over the changes and continuities of Black British life along Railton Road. It was no longer the frontline; it was being gentrified. But the ghosts of those days in the 1980s still linger.

About the contributors

Jacqueline L Scott

Jacqueline L Scott is a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto, and a fellow at the Safina Center. Her research is on the perception of the wilderness in the Black imagination; in other words, how to make outdoor recreation a more welcoming space for Black people. It is part of a wider project on the entanglements of race, place and nature.

Yvonne Maxwell

Yvonne Maxwell is a Saint Lucian-Nigerian documentary photographer, writer and columnist whose work covers stories on migration, social justice, culture and identity of the Black communities within the UK and the wider Black diaspora. Her work has been published in Vittles, Resy, Belly Full and Eater, among others.