There’s power in knowledge. Closing her series on pain and endometriosis, Jaipreet Virdi celebrates the magazines, online communities and self-help books that help women share information on their condition and its treatment.

Pain and the power of activism

Words by Jaipreet Virdiartwork by Anne Howesonaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

I first learned about endometriosis the same way I learned about health and wellness: from articles in Self magazine. The magazine was great for teaching me new workouts and recipes, but with hindsight, I also realise it helped trigger my teenage obsession with achieving my ‘best body’ and confidence. That is, a slim, healthy body cultivated by empowerment.

Self covered the multifaceted aspects of endometriosis through clinical and personal stories. Articles covering misdiagnoses, dealing with pain, new research and reproduction issues were placed alongside feature boxes instructing readers how to recognise disease symptoms. I had never thought much about the disease, for why would I? I had painful periods, but nothing as severe as experienced by others profiled in the magazine, nor was I concerned about fertility.

More: A woodcut of a caesarean prompts a personal memory.

In my twenties, I came across Maegan Tintari’s blog and savoured her DIY fashion posts. The blog was also her platform for sharing her (in)fertility journey and struggles with endometriosis. I empathised with her, but never did I think I would share the same pain and trauma as Maegan did. When I received the diagnosis of endometriosis, one night I found myself rereading Maegan’s old posts. Then I started reading other people’s stories. It was from them I learned about the disease, far more than I ever did from medical experts.

Challenging conventional thinking

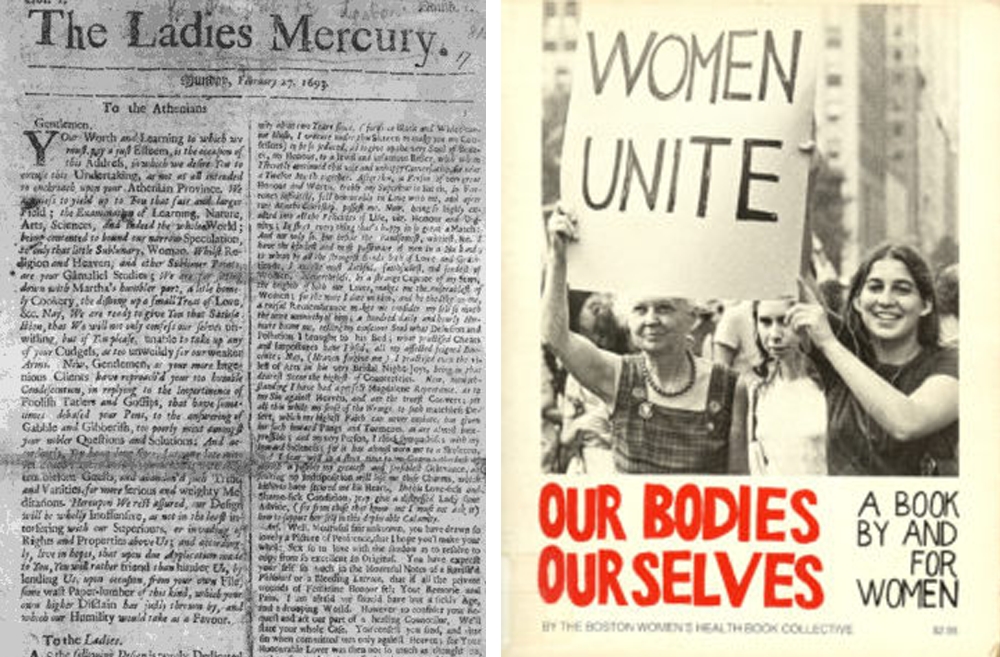

The first women’s magazine only lasted four issues. The Ladies’ Mercury emerged in 1693 to offer British women advice on matters of love and sex. Written by a man who tried but failed to capture the intricacies of women’s lives, the Ladies’ Mercury set the format other women’s magazines later followed.

Most of these were aimed at an upper-class readership, but by 1852, the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine emerged to target middle-class readers. Other 19th-century periodicals took on more political overtones, campaigning for women’s suffrage and for them to have social identities outside of the home, while also offering advice on fashion, motherhood and cooking.

I started reading other people’s stories. It was from them I learned about the disease, far more than I ever did from medical experts.

More importantly, these magazines fostered a kind of virtual community. Readers wrote articles on domestic and political life, shared their poems and stories, asked and answered questions. They also criticised medical elitism, joining in the Popular Health Movement of the 1830s and 1840s to oppose the dangerous ‘cures’ promoted by doctors and advocate for less invasive approaches to health and hygiene.

Frustrated by how doctors’ harsh treatments failed to treat or cure her sister Sarah’s illness, Harriot Kezia Hunt formed the Ladies’ Physiological Society in 1843 to offer women a forum for learning about their bodies and exchanging home remedies for pain and reproductive advice. The society eventually became the Ladies’ Physiological Institute, a progressive organisation offering self-help courses on anatomy, hygiene and childbirth.

By the 1970s, women’s health activists had transformed crucial aspects of medicine, securing important patient rights from a condescending medical system. They challenged conventional thinking about the female body and demanded access to information about their own health. As feminist cultural critic Ella Shohat argues, while medical writings presented endometriosis as the result of disordered female biology, behaviour and personality, self-help books and memoirs about endometriosis serve to advocate awareness of the disease.

Magazines have sought to create communities of women for hundreds of years, and often impart health information.

The first commercial book by women for women that contained information on endometriosis was ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’, produced by the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective in 1973. As Kate Seear explains in her 2014 book ‘The Makings of a Modern Epidemic’, the first edition of ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’ mentioned endometriosis only briefly, with four paragraphs outlining the disease and its principal symptoms.

The 1984 edition, however, expanded the discussion by providing a more detailed analysis and criticising the label of “career-woman’s disease”, as well as challenging anachronistic perceptions of menstrual pain and reproductive choice. The publication, Seear argues, paved the way for more formal lay discourse on endometriosis: Julia Older’s ‘Endometriosis’ also appeared in 1984, providing the first full-length book on the topic.

Self-help books on endometriosis, says Seear, “tend to materialise endometriosis, variously, as a chronic, incurable or disabling condition, with a range of possibly devasting personal, emotional, and financial ‘effects’”. They serve to increase access to information about the disease, clarify medical misconceptions, and perhaps above all, urge sufferers to take action – over their health and for advocacy. Even if endometriosis has no cure, these books and associated websites and blogs offer hope that the disease and the debilitating pain, at the very least, is manageable.

Visible and invisible scars

Since 1948, when endometriosis first appeared in popular literature, the disease has been addressed as a fertility problem. Women are assured by medics that the pain is a part of life, something to be managed and dealt with. As a result, too many women suffering from debilitating pain from endometriosis are overlooked or misdiagnosed. But by the 1990s and 2000s, endometriosis became perceived as an invisible and neglected disease that was serious enough to become an “epidemic ignored”.

Activists are helping to make the disease more recognisable. They insist women’s pain should be taken seriously and argue for the reclassification of endometriosis away from a “low value” disease that is hardly a concern except in relation to reproductive health or in association with certain forms of cancer, including ovarian, breast, melanoma and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. They draw attention to the visible – and invisible – scars on their bodies to highlight the trauma of endometriosis.

Today, campaigns to raise awareness of endometriosis and push for better funding for research are widespread and visible online.

Photographer Georgie Wileman’s series ‘This is Endometriosis’ captures the cruelty of the disease. Abby Norman has created an online community for women to share their stories. Celebrities speak publicly about their experiences: Lena Dunham, Padma Lakshmi, Halsey, Tia Mowry, and more.

In 2000, President Clinton signed a law making pain control and research a priority, declaring the next decade as a “decade for improving pain”. Nearly 20 years later, endometriosis remains underfunded, under-researched and misunderstood, though in Australia activists have successfully lobbied for a $3.6 million National Action Plan for Endometriosis. More self-help and scholarly books are being published on the subject.

Following the legacy of these activists, I add myself to the body of self-help literature that has circulated in women’s hands over the years. My voice mingles with those of other campaigners, for we all are telling the same story: we want the pain to stop, we want our bodies to be perceived as more than vessels, for the medics to take our suffering seriously. Endometriosis needs to be reframed as a disease, not a “women’s health issue” – our reproductive capability should not matter more than our pain.

In the meantime, I continue working, raising awareness and gathering more materials to write a comprehensive history of this disease. I live in the moments when I am free from the pain, before again becoming aware it is creeping back.

About the contributors

Jaipreet Virdi

Dr Jaipreet Virdi is a historian of medicine and disability based at the University of Delaware. Her first book, ‘Hearing Happiness: Deafness Cures in History’ is available where books are sold. She is currently working on her next book, ‘An Invisible Epidemic: The History of Endometriosis’.

Anne Howeson

Anne Howeson develops projects concerning place, time and communities. She is a Jerwood Drawing Prize winner with drawings in the collection of the Museum of London, the Guardian News and Media, St George’s Hospital and Imperial College London. She was shortlisted in 2014 for the Derwent Art Prize and the National Open Art Award, and in 2017 for the Ruskin Prize. She has twice been an invited artist with ING Discerning Eye. As a tutor at the Royal College of Art she promotes drawing in all its forms – through process, outcome and as a way of thinking.