As Indians began to rebel against colonial rule, the British accused them of spreading cholera, little imagining who was really to blame. The terrors that confronted one colonist show how alarming the outbreak had become.

The colonist who faced the blue terror

Words by Anna Fahertyaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

India, 1857. In a British enclave, Katherine Bartrum watches her friend, and then her family, succumb to the deadly cholera.

At 15:00 on 29 June, 23-year-old Bartrum, an Englishwoman living within the fortified walls of a British complex in the north Indian city of Lucknow, watched as her friend was taken ill with cholera. It was the disease most feared by British residents in India, but also by their compatriots back home, both for its rapid and horrific onset and for what it came to symbolise.

During Bartrum’s bedside vigil, her friend would have experienced severe diarrhoea, losing litres of fluid. Vomiting and writhing in pain, her thirst would have been unquenchable and her eyes and cheeks may have sunk into her face. Most startlingly, her lips, fingernails and skin would probably have turned an eerie shade of blue.

A girl suffering from cholera.

Within three hours the cold and clammy “dews of death” gathered on the patient’s brow and she lost consciousness. By 20:00, as her now motherless child slept unawares, Bartrum’s friend was already in her coffin. Surprisingly for the wife of a medical officer, this swift demise was Bartrum’s first experience of “death in any shape”. Yet, just a month before, cholera had claimed the life of the Commander-in-Chief of British India. Bartrum was also destined to encounter the disease again in the coming weeks.

A 23-year old woman before and after contracting cholera.

Cholera had been known in India for hundreds, if not thousands of years, but for centuries it was limited to the Bengal region in the east. The “blue terror” travelled across India – and beyond – as the British expanded their grip on a country that had been under the control of the British East India Company for a century.

As the leading cause of death among British troops in India, cholera earned itself a reputation as an insidious, violent enemy, always ready to attack. The British viewed Indians – and their “very loose habits” – as the natural cause of the disease, but the British themselves acted as carriers. Their large-scale troop movements aided cholera’s emergence from Bengal, British soldiers fighting on India’s northern borders introduced the disease to their Afghan and Nepalese opponents, and British troops carried it to the Persian Gulf, when they were deployed to Oman.

Nineteenth-century map showing routes of cholera from India to Europe and North America.

Even civil interventions by the colonial power contributed to cholera’s spread. By the time Bartrum arrived in Lucknow, the country’s first railway and the world’s largest canal – a network of routes spanning over 1,000 km – had opened. Both aided cholera’s expansion across the country.

Many Indians blamed the British for cholera’s spread, albeit for different reasons. Some believed cholera was meted out as divine retribution when the British defiled holy places or slaughtered cows, which are considered sacred in the Hindu religion. Others felt the disease was caused by deities who resented British rule. Since Indians were just as likely to catch cholera as the colonists, this meant the wrath of these gods was also targeted at Indians, who had failed to stand up to the British.

Cholera reached the heart of the British Empire too. When the first of four major cholera epidemics hit Britain in 1831, killing around 30,000 people, this ‘new’ disease sparked increased debate and a frenzy of analysis. For many years opinion was divided between those who believed cholera was spread through contact and those who blamed bad air and/or the effects of soil temperature. In the ten years before Bartrum arrived in Lucknow, efforts to understand the disease led to the publication of over 700 cholera-related books in London alone.

Studies of cholera outbreaks and causal factors

Measures of mortality and temperature each week in London between 1840 and 1850.

Cholera deaths and meteorological data for each day in England during 1849.

Prevalence of cholera in different English districts during the 1849 epidemic.

Locations of deaths from cholera around the St James and St Anne areas of London during the 1854 epidemic.

Map of the London parish of Bethnal Green showing the “cholera mist” in 1848–9.

Cholera map of London in 1849.

These studies served a purpose as epidemiological tools, but they also gave credence to politicised social policies. As the science of epidemiology developed, medicine shifted away from analysing the behaviour of individuals to investigating issues related to entire populations. These ranged from the nature of the water supply in specific parts of a city to the characteristics thought to be shared by a particular race. In the eyes of 19th-century Brits, the people of India – who were once viewed as fastidiously clean – were thought to be disorderly and dirty.

Bartrum’s uninviting house in Lucknow was certainly dirty, but filth was also a fact of life in England. However, the 1848 Public Health Act – prompted by Edwin Chadwick’s report on the sanitary conditions of the labouring classes – now set England apart from India. While the home country was taking steps to bring filth and disease under control, India was viewed as stagnant and lacking self-discipline, like the immature child of the great British parent. In this climate, cholera came to symbolise the aspects of Indian society most feared by Europeans.

Fear was the reason Bartrum herself had come to Lucknow. She had arrived seven weeks before, leaving her husband at another military station after Indian soldiers mutinied and killed civilian Europeans living in the city of Delhi. This event marked the start of India’s First War of Independence, and soon led to a six-month siege of the city where Bartrum had taken refuge. From this point on, to British eyes, India was increasingly a place of barbarism.

John Bull defending Britain against the invasion of cholera, 1832.

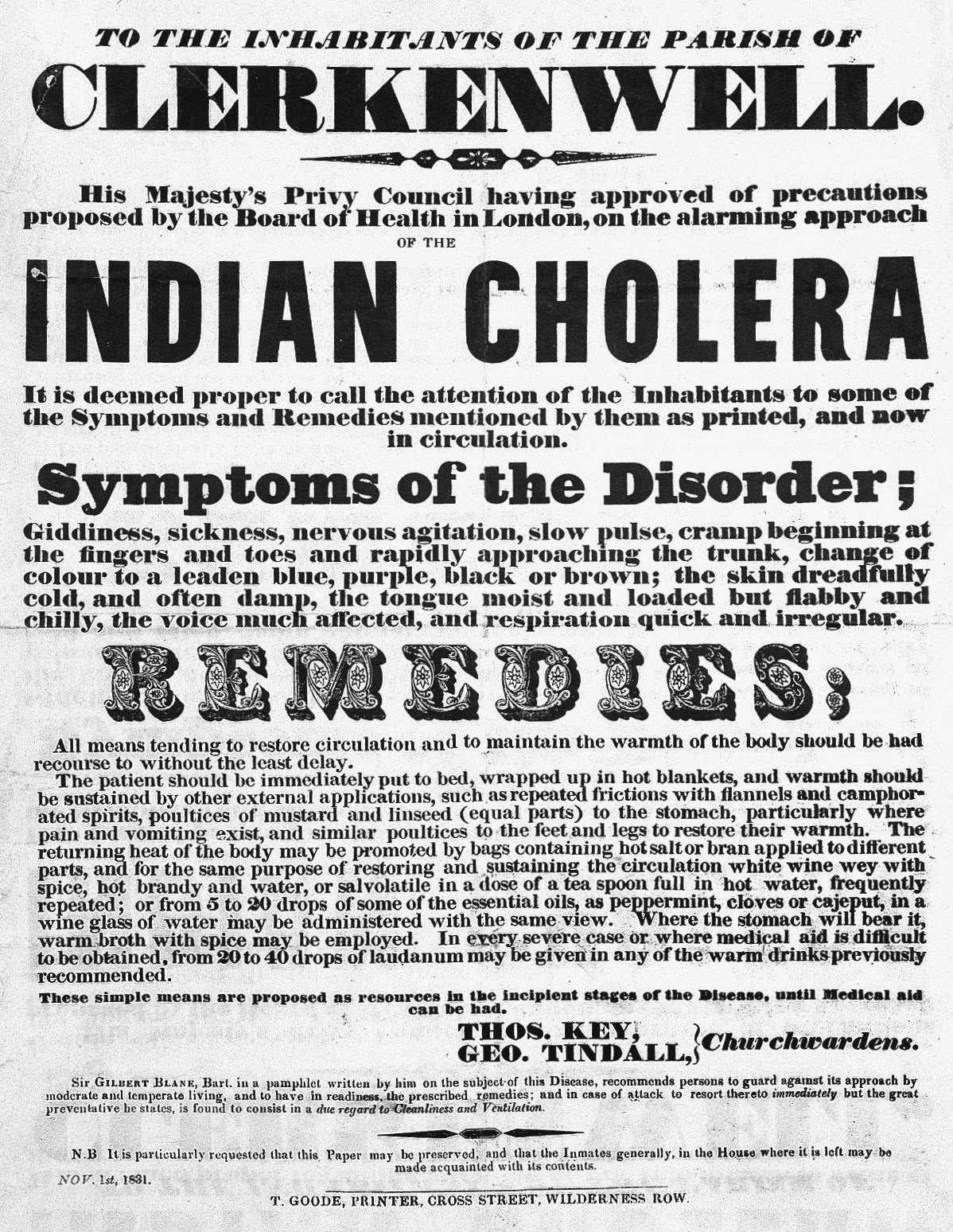

Poster warning of the “alarming approach” of what was described as “Indian” cholera, produced in London in 1831.

In London, Dr John Snow had argued in 1849 that cholera was caused by swallowing poisonous matter that was transmitted through faeces and contaminated water. However, his views did not gain acceptance until at least a decade later. In the meantime, the British medical establishment maintained the stance that Indians were somehow fundamentally different from Europeans. Though scientific investigations found little evidence that race played any role, Indians were inextricably linked with the cholera they were thought to produce.

Nineteenth-century caricature revealing the microscopic impurities found in London’s drinking water.

Of course, if India and Indians were viewed as irredeemably unsanitary, the British administration could excuse itself from spending time and money trying to improve conditions. Susceptible areas in England were seen as unhealthy and vulnerable until improved; India, on the other hand, was beyond hope. Medical theories – despite the evidence – supported the differing political moods at home and abroad.

In England cholera was an alien invader, a colonist in its own right, occupying both the body and the land. As epidemic followed epidemic, people feared the disease might eventually ‘settle’, taking over the country. At the same time, the British administration in India prioritised the health and comfort of its own troops above all else. The Indians now fighting to eject the British from their homeland had to live in far worse conditions.

Just as these Indian rebels laid siege to Lucknow, Katherine Bartrum’s 17-month-old son Bobbie contracted cholera. Though the doctor told Bartrum her son was dying, she administered “the strongest remedies that could be given to a child” and knelt by his bed all night. By morning the outlook was better: Bobbie “began to revive, sat up, and looked so bright”.

Despite being struck down herself the following day, and discovering two months later that her husband had been killed in action, Bartrum and her son managed to survive until the British withdrew from Lucknow four months later. The pair then travelled to Calcutta and boarded a ship bound for England. The night before it set sail, Bobbie, who had been growing weaker by the day, died.

Poster advising residents of east London not to drink unboiled water during the 1866 cholera epidemic.

When Bartrum arrived back in England, London was in the midst of the ‘Great Stink’, a summer in which the stench of excrement from the Thames became so intolerable that politicians launched a project to develop a citywide sewer system. England experienced its last cholera outbreak eight years later. In London it was localised to an area not yet connected to the new sewage network. But in India millions of people died in later outbreaks. Today cholera remains, as it was before the 1800s, endemic in some areas of the country.

About the author

Anna Faherty

Anna Faherty is a writer and lecturer who collaborates with museums on an eclectic range of exhibition, digital and print projects. She is the author of the ‘Reading Room Companion’ and the editor of ‘States of Mind’, both published by Wellcome Collection.