Waves of migrants to the Caribbean brought with them largely vegetarian diets that became part of the Afro-Caribbean way of life. Riaz Phillips uncovers the religious roots of Caribbean dishes in London, and explores the natural way of eating for health in Jamaica and the wider Caribbean.

Natural eating in Jamaica and the Caribbean

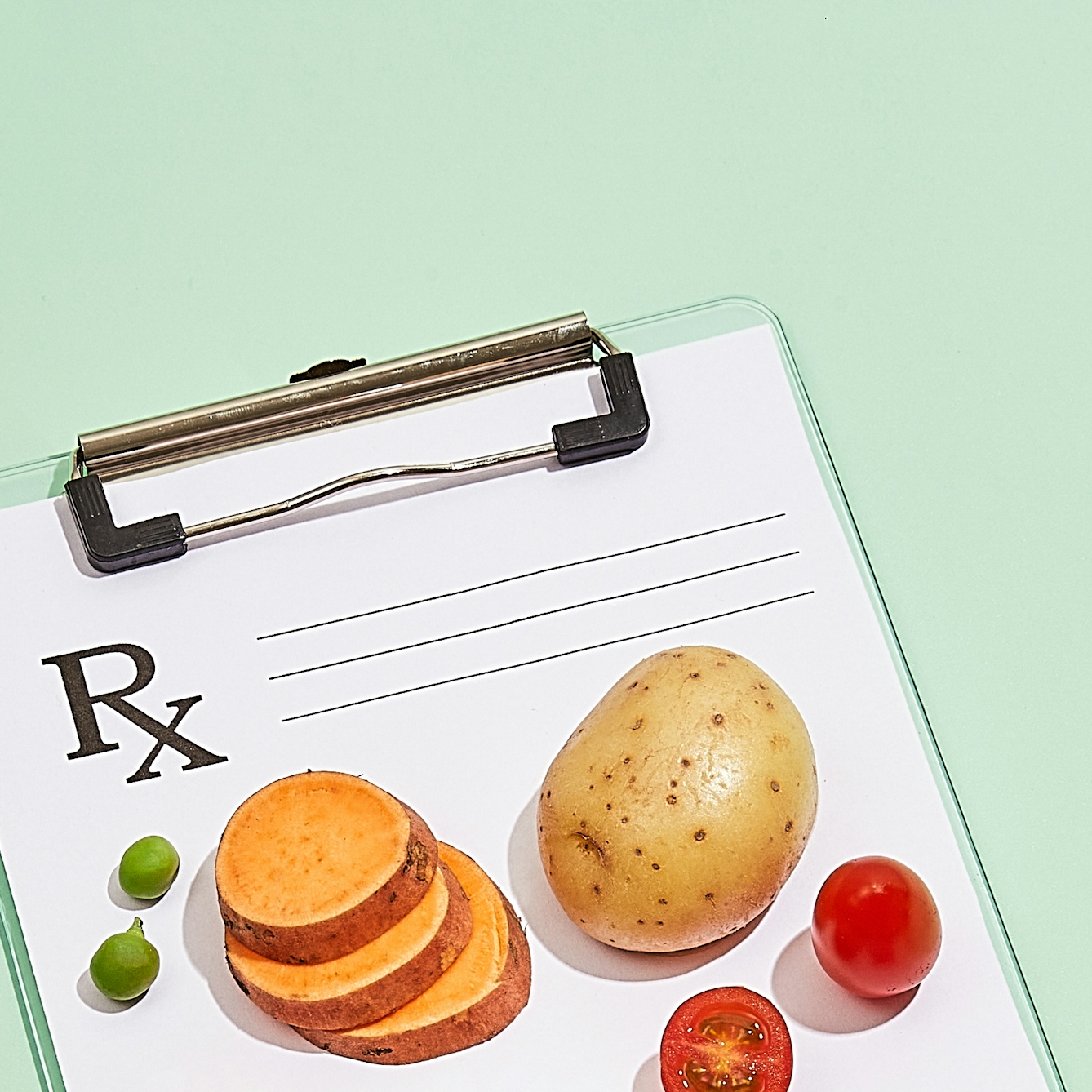

Words by Riaz Phillipsartwork by Anna Keville Joyceaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Article

Eating for health is common across the Caribbean. In Jamaica, most towns and cities have places selling fully vegan Ital food, centred around curries and stews that are synonyms for healthy eating and important enough to be priced the same as their carnivorous counterparts.

Likewise, in Trinidad and Guyana it is possible to find roti shops with predominantly ‘plant-based’ menus, with flour and pulse breads served with blended or cooked-down vegetables, like tomato choka and pumpkin talkari. These have existed for decades without the need for a trendy moniker or the hype from social-media stars.

Yet eating for unhealth is rife too. A few years ago, at a Rastafarian community in the hills of Ocho Rios, north Jamaica, I spoke to a lady named Dawta Monika, a 69-year-old market vendor from Kingston who told me that, “When I was a young girl, people didn’t have all these things. High blood pressure, diabetes, cancers – all the things that people have today. Things that are killing us.”

What she refers to are the creeping advances of internationally owned alcohol brands, sugar-laden snacks and global fast-food chains, which have played a sizable role in both diabetes and heart disease being in the top three causes of death for people under 70 in Jamaica.

I visited Ocho Rios in order to learn more about the different subcultures and lifestyles in Jamaica, particularly those who have been able to escape the encroaching clutches of the commercial food industry, and how the diet of Jamaica’s diet is and has been shaped by its past.

A wealth of culture existed within the Caribbean before Europeans ‘discovered’ the island group in the 1400s. The islands were mainly inhabited by the Arawak and Taino Amerindian tribes, who ate for health as a byproduct of eating for survival, hunting game, birds and reptiles, as well as farming produce that could be grown with relatively small maintenance.

“I visited Ocho Rios in order to learn more about the different subcultures who have been able to escape the encroaching clutches of the commercial food industry.”

Vegetarianism and religious belief

Today the majority of people who reside here are the descendants of various generations of slaves brought from West Africa by European colonisers during the transatlantic slave trade. These enslaved people worked tirelessly under the relentless sun producing sugar, rum and cotton, and were limited to the diets that were possible using food from areas of low-quality soil called ‘provision grounds’ – where they grew starchy root vegetables like yam and cassava – and bulked out with any extras they were given, such as salted meats and fish. Their recorded heights (a commonly used metric of health) and subsequent high mortality rates suggest that eating for sustenance took precedence over health.

After the slave trade was disbanded in the early 1800s, it continued on in all but name with indentured workers, primarily from the north of India and also southern China, brought over to the islands. At the turn of the 20th century, with consecutive waves of migrants to the island, a new way of looking at health and food on the islands was informed by religion, notably Hinduism and Islam (mainly in Trinidad and Tobago, and Guyana) and, in Jamaica, Seventh-Day Adventism and Rastafari, a Christian-centred religion overwhelmingly practised by West African descendants.

The idea of personal health by way of diet is a beneficial side effect rather than the main goal, which is in contrast to the commodified confines of healthy eating promoted in the West.

The presence of these religious customs is reflected in the food shops on high streets and markets. In Islam, certain ideas or behaviours might be considered haram (forbidden), such as pork consumption. In Hinduism, the idea of ahimsa – an ideal of non-violence influenced by Buddhism and Jainism – informs the popularity of vegetarian diets, while the cow’s special status means non-consumption of beef.

In Debe, a town to the south of Trinidad, lies a row of locally famous stalls reflecting this, which includes Hosein’s Delicacies, selling (without labelling them as such) a fully vegetarian roster: aubergine-based baiganee, split peas kachori and potato-based aloo pie. The Rastafari have their concept of Ital, rooted simultaneously in the idea of equality between all of God’s creatures and only eating natural plant-based produce in the form of stews, soups and curries laden with root vegetables like yams and dasheen. Finally, the Seventh-Day Adventist Christians also practise vegetarianism for similar reasons to the Rastafari, with their diets very much aligned.

“At the turn of the 20th century a new way of looking at health and food on the islands was informed by religion, notably Hinduism, Islam, Seventh-Day Adventism and Rastafari.”

The vanity of Western healthy eating

What underpins all these disparate philosophies is that they hope to foster a sustainable ecosystem that champions an anti-industrial society and maintains the equilibrium and condition of the planet. These habits come from a community-based generational system where eating patterns are so deeply rooted that they are unlikely to be dropped at a whim.

Here, the idea of personal health by way of diet is a beneficial side effect rather than the main goal, which is in contrast to the commodified confines of healthy eating promoted in the West, where there always seems to be some element of vanity involved (as well as various commercial interests tucked in somewhere, to boot).

When health became associated directly with individual desires rather than any collective goal of sustainability, those peddling things such as weighing scales, diet-driven media, gym memberships, weight-loss ‘nutrition’, low-fat foods, approved ‘health foods’, and ‘superfoods’ like avocado, spirulina and sea moss (which, ironically, are simply foods commonly eaten in places like the Caribbean for centuries, which have been gentrified) all stood to gain. As friend and restaurateur Gabriel Pryce aptly remarks to me in conversation about these initiatives, “they are sold on fear”.

The fast-food invasion

In recent decades, the Caribbean has been susceptible to these same deleterious negative impacts of bad diets as pretty much most of the world. As American culture began to permeate the void left by the British exodus after Jamaican independence in 1962, American brands, by way of radio and television, became seen as aspirational. This meant that the bright lights of oil- and sugar-heavy fast-food chains, the shiny packets of snacks seen in TV commercials, and product placement of blockbuster films began to take hold, with local food shunned in the process.

This led to plazas and roadside malls reminiscent of the American heartland, lined with the biggest names in global fast food. Shaming for deviating from certain shapes of acceptable bodies started to happen in ways that had not societally occurred in the Caribbean before. Yet during my time in Jamaica, I have seen the bucking of this trend initiated by social media access and the sharing of information about the impact of commercially processed food diets.

Many see the ideals of healthy eating – be it the reduction of processed food and meat-eating, or following state-issued dietary guideline suggestions that highlight plant-based eating – as a reversion to their elders’ culture. Beyond homages to Ital food, this also shows itself in the renewed interest in the consumption of sea moss and also natural juice bars, small changes that stand in contrast to the dramatic, life-altering changes that Western diets tend to promote.

“In recent decades, the Caribbean has been susceptible to the same deleterious negative impacts of bad diets as pretty much most of the world.”

Food as medicine

Diaspora like myself exist somewhere in the nether realm between the two regions. We find ourselves in the midst of Western modes of health-consciousness, but with a pre-existing knowledge of food that other people in the UK aren’t aware of. Fortunately, the growth of Ital shops and roti shops in the UK help facilitate the movement towards alternative diets and help educate people that there is another health-food world outside the one they’ve been repeatedly sold.

At the more traditional Caribbean take-outs, while change is slower, in many there are signs of reckoning. At one of my favourite spots in north London, Roti Stop, this includes labelling juices as having no added sugar and providing wholemeal versions of popular flour-based foods like roti, showing a recognition for the importance of healthy eating, even if it is being driven by consumer spending patterns.

Although my relationship with plant-based healthy Caribbean food developed in the Caribbean, it was at these places in the UK and the conversation that occurs inside them, talking to the owners, that began my journey to awareness around the deeper dialogue of eating and environmental sustainability. This was my avenue to a few years of veganism before settling on flexitarianism, with dramatically less meat. My new diet was fostered in those spaces rather than the Whole Foods Markets and organic shops that I never truly felt were for me – quite literally because they were never in the places I or my family resided.

Music has also played a huge role as an influencer. From Horace Andy swooning about a vegan diet in the 1970s track ‘Ital Vital’, Super Cat’s 1980s smash hit ‘Vineyard Party’, where he waxes lyrical about the produce of Jamaica or, more recently, global star Chronixx’s tune about health food, ‘Spirulina’, the existence of an inclusive discourse and some form of personal grounding around healthy eating smooths the pathway to adoption, offering an alternative to a mode of Western healthy eating that at every step excludes those from marginalised backgrounds.

The conclusion to this is not to say that everyone in the UK needs to convert to Rastafari but rather to suggest what can be learned from those who practise it. As Chronixx in ‘Spirulina’ echoes, the old Rastafari adage is “mek you food be yuh medicine”.

About the contributors

Riaz Phillips

Riaz Phillips is a writer, researcher and film-maker born and raised in London, UK. He studied Politics and Economics at university in London followed by International Studies at the University of Oxford. Following a short-lived career in the corporate world, he began a pursuit to champion the heritage of his family. His books ‘Belly Full: Caribbean Food in the UK’, ‘Community Comfort’ and ‘West Winds: Recipes, History and Tales from Jamaica’ are the result of this.

Anna Keville Joyce

Anna Keville Joyce, Food Artist and Creative Director, is originally from the USA and currently based out of Buenos Aires, Argentina, and New York City. With a background in food styling, design and anthropology, Anna has participated in a wide variety of photography, film, and installation projects worldwide, and has been featured in numerous publications and exhibitions. Her creative spark, attention to detail, and keen sense of composition has allowed her to gain a broad international client and she has the pleasure of collaborating on increasingly creative and dynamic projects.