A Nigerian ritual headdress in Wellcome Collection prompted anthropologist Chimemwe Phiri to think about the ways we pass on important information to younger generations. Here she focuses on ideas and knowledge about fertility.

Mask, ritual and fertility

Words by Chimwemwe Phiriphotography by Steven Pocockaverage reading time 4 minutes

- Article

Having children and starting a family, choosing not to or not being able to, are topics that affect everyone. Fertility is an enormous and complex subject and, as I think about my own journey, the subject feels heavy. I think about what I need to know if I decide to have kids in the near future, and I think about the ways people, especially women – past and present – have found a space for these important discussions.

I am a researcher in anthropology and have examined the role of masks as symbols of fertility over generations. I have looked at how they are used to educate people, and at their association with initiation rites.

My fascination with masks began when I first saw masquerade dancers perform at a holiday resort in Malawi, where I am from. I was eight years old, and the image of the dancers, their costumes and the mystery that surrounded them instilled a sense of both fear and respect in me. The masquerade I saw, ‘Gule Wamkulu’ (‘The Great Dance’) is found among the Chewa ethnic group and is commonly performed at funerals and special ceremonies.

Chewa dancers are believed to embody ancestral spirits wishing to connect with descendant communities in order to teach them about the unwritten moral code, the mwambo. If you are in Malawi you can witness performances as a form of entertainment in many tourist spaces. But there is also a tradition attached to fertility.

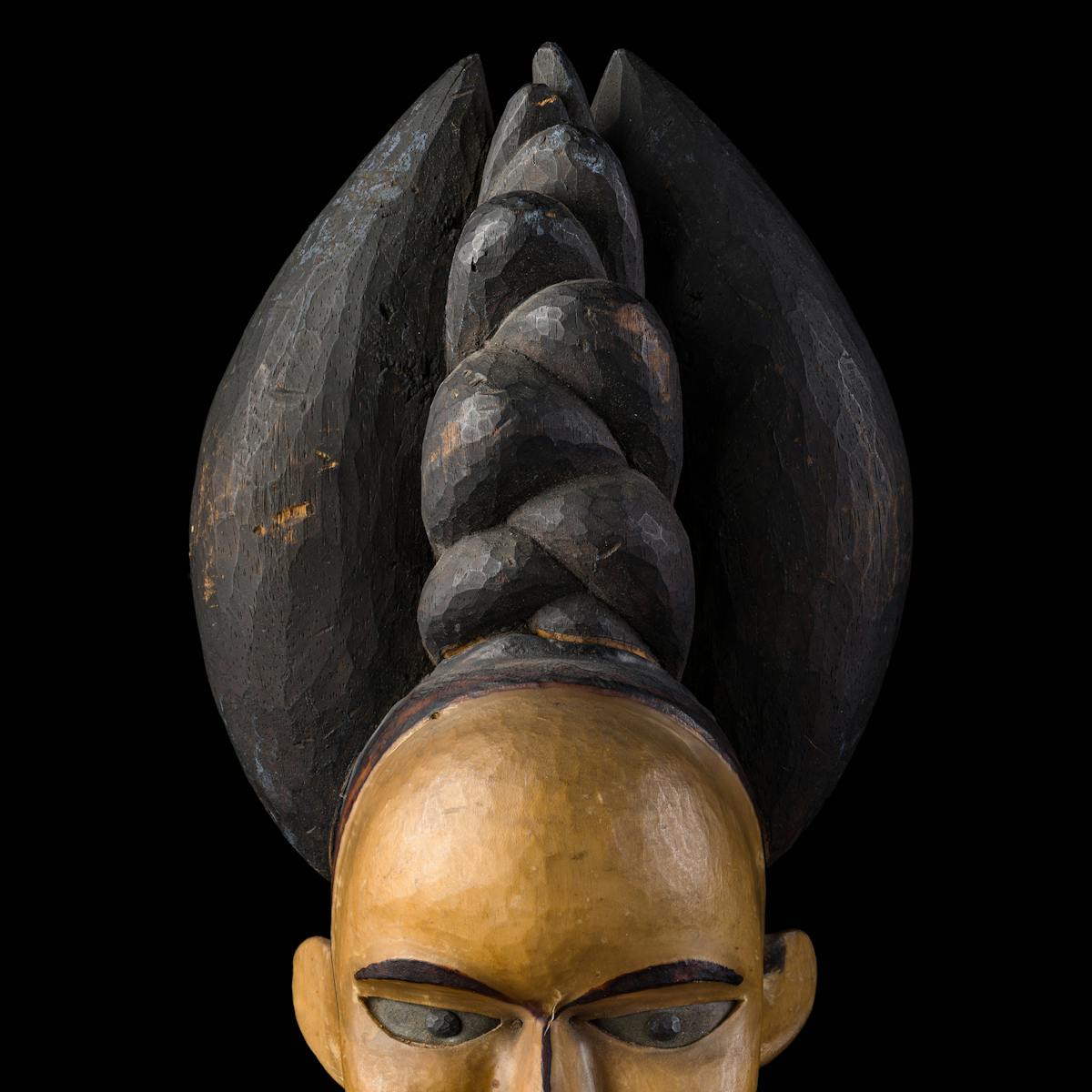

Skin-covered headdress from the Cross River region of Nigeria.

Initiates are given advice on topics such as their future roles as fathers and mothers, pregnancy and sexual behaviour, including sexual taboos.

All ‘Gule Wamkulu’ masks are based on the Kasiya Maliro structure. The meaning of the name is “the one who accompanies the corpse to the grave”, and in its physical manifestation it assumes an antelope shape and is interpreted as an inverted womb. This explains its connection to the cycle of existence in Malawian communities: death, life and other important events in between.

Kasiya Maliro dates to prehistoric times, and variants of the mask continue to appear today at initiation ceremonies for both boys and girls. In these ceremonies initiates are given advice on topics such as their future roles as fathers and mothers, pregnancy and sexual behaviour, including sexual taboos.

The colonial collectors

In 2018 as a graduate student in Visual and Museum Anthropology at the University of Oxford, I had the opportunity to visit the Science Museum’s storehouse at Blythe House, London to see objects sourced from Africa.

From the 16th century onwards, and particularly during the colonial era, a large number of culturally important items were removed from their countries of origin and deposited in Western museums. Collectors were interested in the anthropological, aesthetic and medical aspects of the objects they came across, and grouped them into the following categories: primitive, traditional or folk medicine. These categories fail to consider the diverse health and healing knowledge systems of indigenous practices.

On display in ‘Medicine Man’ at Wellcome Collection is an impressive skin-covered headdress that was most likely sourced from the Cross River region of Nigeria (masks of this type are unique to these regions of Nigeria and Cameroon). Such headdresses were worn on top of the head by masquerading performers at events like initiations and funerals.

The mask is open to many interpretations.

Like masks from neighbouring West African cultures, the headdress may have been used for educational purposes related to communication about fertility. It was probably associated with prayers and rituals for material wellbeing and earthly blessings, such as fertility, the birth of many children, and continuity of life.

The skin-covered headdress and Kasiya Maliro emphasise different cultural understandings of fertility and reproduction, which were, and are, important knowledge for many societies, conceptualised and communicated in specific ways. However it is worth noting that meanings of masks are open to many interpretations and should not be limited to a singular viewpoint.

Today, human knowledge of fertility, conception and pregnancy has been transformed by medical advances. And the internet has, in many parts of the world, changed the way we talk about these subjects. We can share information and experiences, both positive and negative, easily and openly. But rituals and objects believed to improve fertility still have their place; our proximity to our ancestors is closer than we might think.

About the contributors

Chimwemwe Phiri

Chimwemwe Phiri holds an MSc in Visual, Material and Museum Anthropology from the University of Oxford. Her research focus is on museums’ collecting practices and the history of photography in Africa.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.