Even the dead aren’t safe from digital reanimation and political manipulation. As technology makes it ever easier to twist reality, we face an increasingly urgent question: what are the ethical implications of the ‘deepfake’?

Manipulating the evidence with deepfake technology

Words by A R Hopwoodaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

I remember seeing it for the first time. I was sitting on the sofa with my partner in our old flat watching TV. We were both occasionally glancing at our phones (like you do) when she turned to me and said “you’ve gotta see this”. She held her phone out in front of us on selfie mode and told me to align my face on the screen with one of the two small smiley icons – she did the same. The phone took a long, deep breath until it spat out a startling, uncanny image. The camera was still recording the scene in front of it, but we’d changed – our faces had been swapped onto the other person’s head and we were experiencing the illusion in real time. As I moved my body her face moved with it; as I spoke her jaw seemed to track my speech. In a few seconds I’d lost my double chin and regrown my hair, whereas she’d changed from an elegant beauty into someone who resembled an Amish-styled Nosferatu.

Despite my initial squeals of delight at such wackiness, I actually found the experience of seeing my likeness so convincingly superimposed onto someone else unsettling. I’d not long started my research into false memory and had grown fascinated by a 2002 experiment by Dr Kimberley Wade that explored for the first time how doctored images could affect memory.

More: Designing death in the virtual city

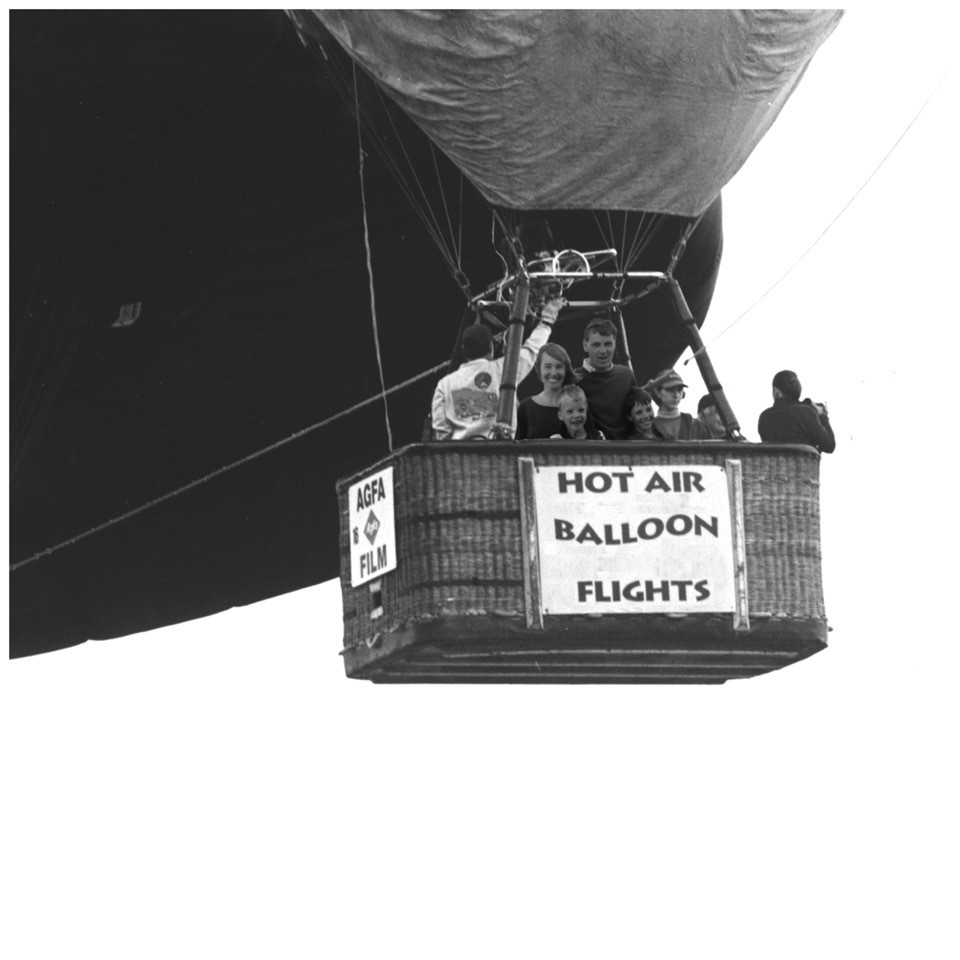

In the study she presented a fake photograph to participants of them enjoying a hot air balloon ride as a child, alongside a series of real images from their past. After subsequent interviews, around 50% of those who took part in the study could remember the false event. As I sat looking at real-time face swap technology for the first time, I couldn’t help but imagine how such extraordinary developments in image doctoring could be used to engineer convincing false memories in far more potent contexts.

Using false photographs to create false childhood memories, experiment by Dr Kimberley Wade

Remembering what never happened

Wade’s balloon study was the first in a number of image-led psychology experiments that explored how faked evidence can work alongside suggestion from an authority figure to create false memories. But when the encounter with a doctored image is in an everyday setting, the influence is still more profound.

In 2010 the cognitive psychologist Steven Frenda designed a series of doctored political images in collaboration with the US online magazine Slate. This included one of Barack Obama shaking hands with the Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and a faked photograph of George W Bush holidaying with a baseball celebrity during the Hurricane Katrina disaster. The images weren’t declared as fakes – readers were simply asked to report whether or not they remembered the events depicted and then fill in a short questionnaire that established their political orientation.

More liberals remembered Bush’s insensitivity and a higher percentage of conservatives recollected Obama’s controversial handshake.

Over 5,000 people took part; 50% remembered the ‘events’ happening and 27% recollected seeing the stories play out on the news. Most significantly, more liberals remembered Bush’s insensitivity and a higher percentage of conservatives recollected Obama’s controversial handshake.

This startling study was the first to link false memories elicited by faked photographs with pre-existing political beliefs. However, it only looked at the impact of static images. What if equally convincing fake video footage had been used? Would the effect have been more powerful? Does such technology exist?

The political uses of deepfake

Supasorn Suwajanakorn from Vistec University in Thailand is a computer scientist at the vanguard of video-doctoring technology.

In 2017 his study Synthesizing Obama: Learning Lip Sync from Audio he presented highly-convincing doctored videos of Barack Obama giving a fake presidential address. Using Artificial Intelligence (AI) he created controllable 3D representations of Obama from data derived from thousands of photographs and videos.

One of Suwajanakorn’s original ambitions in developing the tech was to bring significant people ‘back from the dead’ by presenting highly-convincing 3D representations of them to new audiences. During his TED talk, he said of the theoretical physicist Richard Feynman: “wouldn’t it be great if you could bring him back to give lectures to inspire millions of kids, not just in English but any language?”

The unintended consequences and political misuse of such a seemingly wide-eyed technological quest became clear to Suwajanakorn during his studies, and no doubt during the 2016 US presidential elections. Frenda’s experiment presents hard evidence that doctored political static images can produce false memories that reinforce existing prejudices, so there are likely very real risks that such deepfake video technology could be used in the future to spread highly-convincing political misinformation.

Suwajanakorn is attempting to produce counter measures that fight against such misuse of his work through a platform called Reality Defender – a web browser plug-in that can flag potentially fake content automatically. He’s also acutely aware of the challenge of raising public awareness about the pervasive nature of AI-generated political footage. He’s currently working with the AI Foundation and First Draft News – a Google-led initiative to fight online misinformation – to design suitable interventions that keep them ahead of the fakers.

Digital ghosts

Suwajanakorn has legitimate concerns about the political misuse of his technology, but it’s also worth considering the ethics of his original justification for creating it: to digitally render dead historical figures for educational purposes. The notion of informed consent is a key ethical concern in medical practice or when justifying human participation in an experiment. For example, in experimental psychology, researchers should, so far as is practicable, explain what is involved in advance and obtain the informed consent of participants. In experiments where the ‘greater good’ justification for a deceptive process has been approved, then the informed consent must be given after the study has been performed in the form of a comprehensive debrief.

In visual culture, such safeguards are often impossible and sometimes undesirable to enact. Artistic freedom tends to trump all else in such settings. However, there are still legal and ethical concerns that artists have to reconcile – not least in the unapproved use of someone’s image. It’s perhaps fair game for the artist who wants to use image technology to ‘punch up’ at an authority figure, as with Bill Posters’ recent ‘deepfake’ video of Mark Zuckerberg. But is it alright to use a stranger’s image to highlight how facial recognition technology can be used to track down someone on social media, as it was in Egor Tsvetkov’s chilling project Your Face is Big Data?

If someone was to create a controllable 3D representation of Richard Feynman so that he could posthumously deliver his lectures, would his unavailability to grant informed consent render such an ambitious project unethical from the outset? Roy Orbison’s 2018 hologram world tour and similar projects involving uncannily lifelike representations of Amy Winehouse and Whitney Houston have recently brought this question into sharper focus.

My instinctive response is to dislike the idea – not only because of the lack of consent granted by the posthumous performers, but also because it plays to a mawkish nostalgia, where emotion trumps all other considerations. But with its immersive quality and proximity to ‘real’ experience it also feels significantly different to using text, image and video to communicate the legacy of a dead celebrity.

Resting in peace

We’re used to seeing characters in films played by actors who died before the project was completed. We then bear witness to the extraordinary special effects that can render on-screen anything a writer can imagine. These visualisations have until now been produced on huge budgets by skilled technicians. However, as such technology becomes more user-friendly, it’s clear that it carries risks in the political realm as well as great creative potential in visual culture.

Understanding how such footage actually works to influence memory and belief ‘in the wild’ is a pressing concern that calls for an interdisciplinary response. In a near future where it’s possible to easily create convincing digital representations of any kind of truth, we must learn how to guard against our propensity to believe what we want to hear. How do we know when we might be wrong, if we can always engineer footage that can prove us right?

About the author

A R Hopwood

A R Hopwood is an artist and Wellcome Trust Engagement Fellow. He has collaborated extensively with psychologists to create art projects about memory, belief and misdirection, including WITH (withyou.co.uk) and the False Memory Archive. He was co-curator of ‘Smoke and Mirrors: The Psychology of Magic’ at Wellcome Collection in 2019.