Before the Bosnian War, rape had been considered merely an unfortunate consequence of war and had not received much attention from the international community. Artist Jenny Holzer's work 'Lustmord', which translates from German as 'sexual murder', shines a light on the crime from the view of the victim, the perpetrator and the observer. Trigger warning: this story contains mentions of sexual violence.

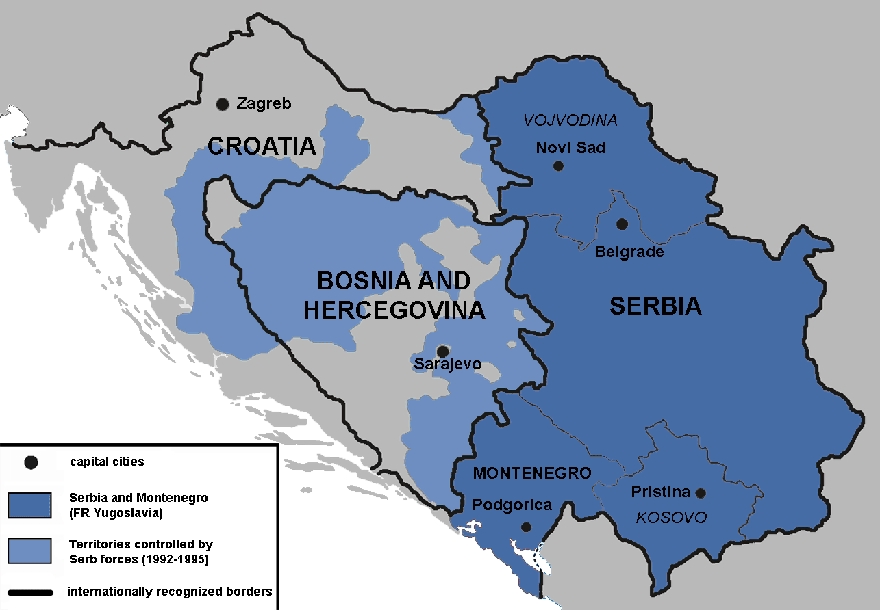

The Bosnian War began in 1992. Marshal Tito, who’d led Yugoslavia from the end of World War I, had died in 1980, destabilising the relationships between the different ethnic groups. A referendum for Bosnia’s independence was held in 1992, which the majority of Bosnians supported; unfortunately, the Bosnian Serbs had a different future in mind for their country.

With the help of Serbia and the Yugoslav People’s Army, they began to ‘cleanse’ certain areas of non-Serbian inhabitants by use of violence. From 1992 to 1995 the Serbian army tortured, murdered and displaced over 2 million people, with the majority of the violence inflicted on the Bosniak Muslims. The Bosnian War, however, brought to the world’s attention an aspect of war that had rarely before been discussed – rape.

Map of Bosnia and Hercegovina, Croatia and Serbia.

Before the war in Bosnia, rape had been considered merely an unfortunate consequence of war and had not received much attention from the international community. In 1992 the first media story about the rape of Bosniaks hit the newsstands and suddenly the victims had a voice and the world had a very grim awakening.

By 1993, pressure from the media forced aid organisations – who had previously remained neutral – to admit to the scale of the problem, and the newly set up International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia (ICTY) to define rape as both a war crime and a crime against humanity. Despite this, by the end of the war in 1995, up to 60,000 women and girls had endured gang rapes, forced impregnation and sexual slavery at the hands of the Serbian army.

In 1993 Jenny Holzer heard about the rapes in Bosnia; through reading UN and Amnesty International reports, news articles and female eye-witness reports, she was inspired to spread the word through her art. Holzer had come to public attention due to her anonymous, graffiti-type art ‘Truisms’, which she had posted over New York in the late 1970s.

A political artist, her Truisms consisted of statements such as “Anger or hate can be a useful motivating force”, “A single event can have infinitely many interpretations”, and “Abuse of power comes as no surprise”. Originally her work focused very much on the written word, but after a brief hiatus from her art, Holzer came back ready to try new mediums and ‘Lustmord’ was born.

‘Protect Me From What I Want’, Jenny Holzer, text on table.

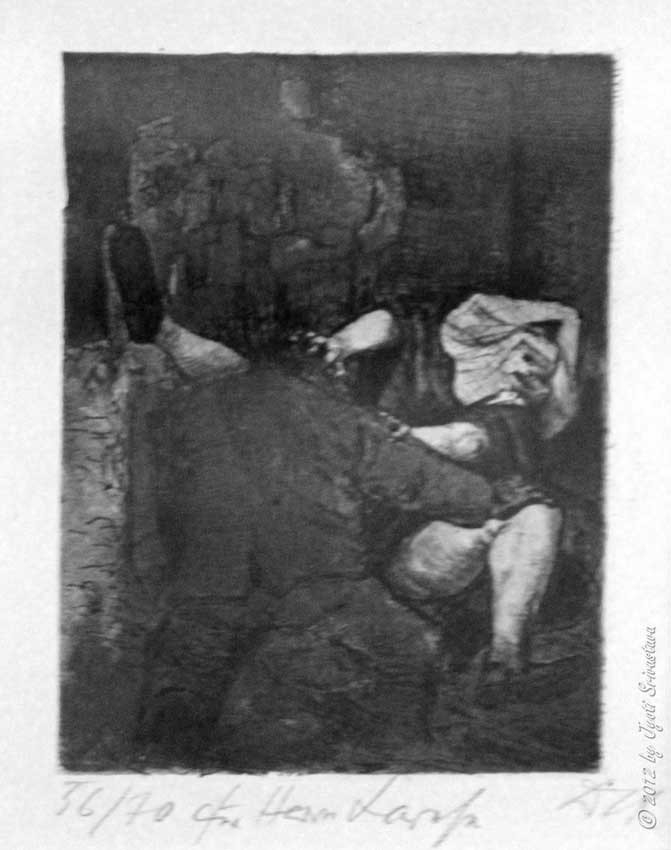

Lustmord is a German word meaning “sexual murder”. Associated in the post-World War I era with artwork depicting disembowelled and dismembered women as the victims of sexual crimes, Holzer’s work seems eerily tame in comparison. Holzer’s work centres around three poems, all showing a different perspective of the crime – that of the perpetrator, the victim and an observer.

The observer may seem an odd, even voyeuristic, choice; it becomes less so when you realise the Bosnian rapes were not just opportunistic spoils of war. Instead, they were organised and systematic assaults on not only individual Bosniak women, but also their entire community. In a culture that prized female purity and chastity, the rapes effectively tore apart families and caused whole villages to flee in terror.

‘War’, Otto Dix (soldier and nun).

Holzer’s poems are created by short lines of text so ambiguous and subtle, they could be referring to any woman or any incident of violent sexual assault. With lines such as “She tightens and I hit her”, “Your awful language is in the air by my head”, and “She is narrow and flat in the blue sack and I stand when they lift her”, the horrific intent is clear while the details are not. Her text was displayed through the use of several different mediums, primarily LED signs, text on human skin and engraved silver rings on human bones.

Various details of ‘Lustmord Table’ by Jenny Holzer, 1996. (Courtesy Sprüth Magers.)

The bones in ‘Lustmord’ were purchased from a dealer in New York and laid out how they would be in a morgue. Disconcertingly, all of the bones represent a part of the body we would normally associate with beauty and sensuality: teeth, shoulders, thighs, ribs, the back, fingers and the pelvic area. Several of the bones wear rings engraved with text from the poems in both English and German, all intermixed, making it difficult to immediately identify which is the perpetrator, which is the victim and which is the observer.

The bones, with their accompanying texts, are a visceral reminder of the hatred, pain and grief that went into every act of sexual violence: “I want to brush her hair but the smell of her makes me cross the room. I held my breath as long as I could. I know I disappoint her” on a vertebrae; “Her breasts are all nipple” on a finger; and “My nose broke in the grass. My eyes are sore moving against your palm” on a leg.

Download the poems (trigger warning): ‘Lustmord’ by Jenny Holzer

On display in our Forensics exhibition in 2015

As of 2014, only 30 individuals have been convicted of sexual violence crimes by the ICTY, leaving the majority of victims still waiting for justice. Several of the accused died before they could be sentenced, while others had their rape charges dropped by pleading guilty to other charges, such as genocide. Many of the victims suffer from ongoing health issues, including depression and suicidal thoughts, while often their attackers still live in their villages and work in positions of power.

While the women of Bosnia may be losing hope, they are not yet forgotten. Angelina Jolie wrote a film about the Bosnian rapes in 2011 and also met with victims in order to raise awareness of rape in war zones. In 2013 the UN’s Special Representative for Sexual Violence in Conflict travelled to Bosnia to speak to victims of sexual violence, and the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict was held in London in 2014. Perhaps one day in the future the international community will find a way to learn from countries like Bosnia, in order to better protect women in conflict.

About the author

Taryn Cain

Taryn Cain is a Visitor Experience Assistant at Wellcome Collection.