Although a less familiar name today, Louis Wain was famous in the early 20th century for his anthropomorphic cat illustrations. He’s now more often seen as having had a ‘tragic’ decline due to mental ill health, supposedly evidenced by dramatic changes in his artistic style and output. But here artist and curator Bryony Benge-Abbott calls for a more positive, nuanced view.

Later this year Benedict Cumberbatch will star in a film about the life of the Victorian artist Louis Wain. Little known today, and often dismissed as a “crazy cat artist”, Wain was one of Britain’s most popular artists in the early 20th century. He was an eccentric who adored cats, delighting the Edwardian public with charming, often witty illustrations of anthropomorphised feline friends playing golf, drinking tea, wearing suits and going to the opera.

Wain’s cats were humanised at a time when they were widely considered pests by the British public, a view unfathomable to today’s nation of cat lovers. His illustrations flooded newspapers and journals with images of charming, loveable felines parodying Edwardian life. His art helped to popularise the idea of cats as household pets.

When demand for his work dropped off during World War I, Wain’s practice evolved to produce ‘futurist’ ceramic cats, rather Cubist in style. This new body of work greatly excited the artist; it offered a thrilling, intuitive method of exploring his favourite subject. Wain later wrote of this period, “I never knew from one moment to another exactly what I was going to do. It was the expression of a mood and it all came out as a surprise to me.”

His paintings and drawings, too, became increasingly abstract. Dynamic, highly patterned designs started to overtake the archetypal ‘Wain cat’, inviting viewers into a new, vibrant world where felines “…became frenzied and jagged, sometimes disappearing into kaleidoscopic shapes”, according to the art historian Frances Spalding. Perhaps these vivid patterns were inspired by his fascination with electricity, still poorly understood by the general public at that time.

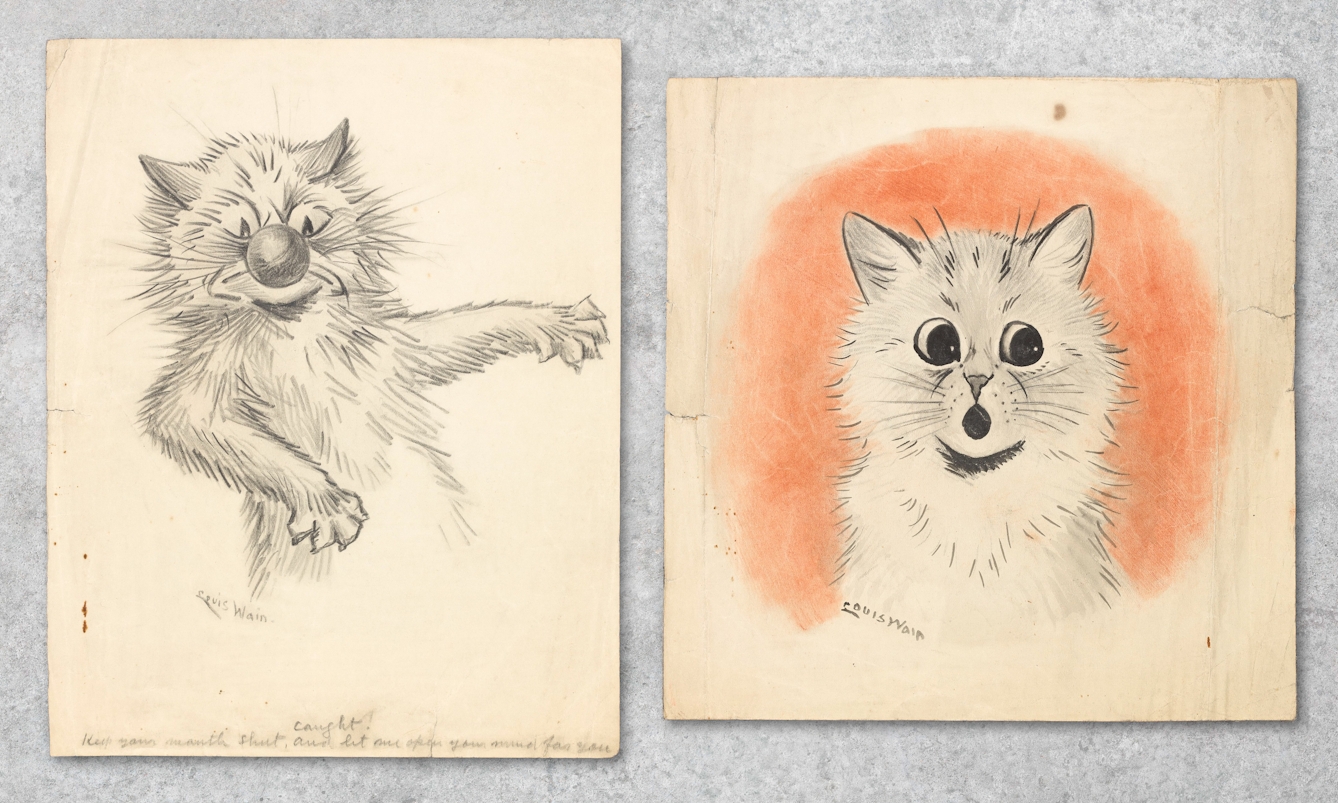

In pictures

Two sketches by Louis Wain from a collection of poems, notes and drawings held in the Wellcome Library(view in catalogue).

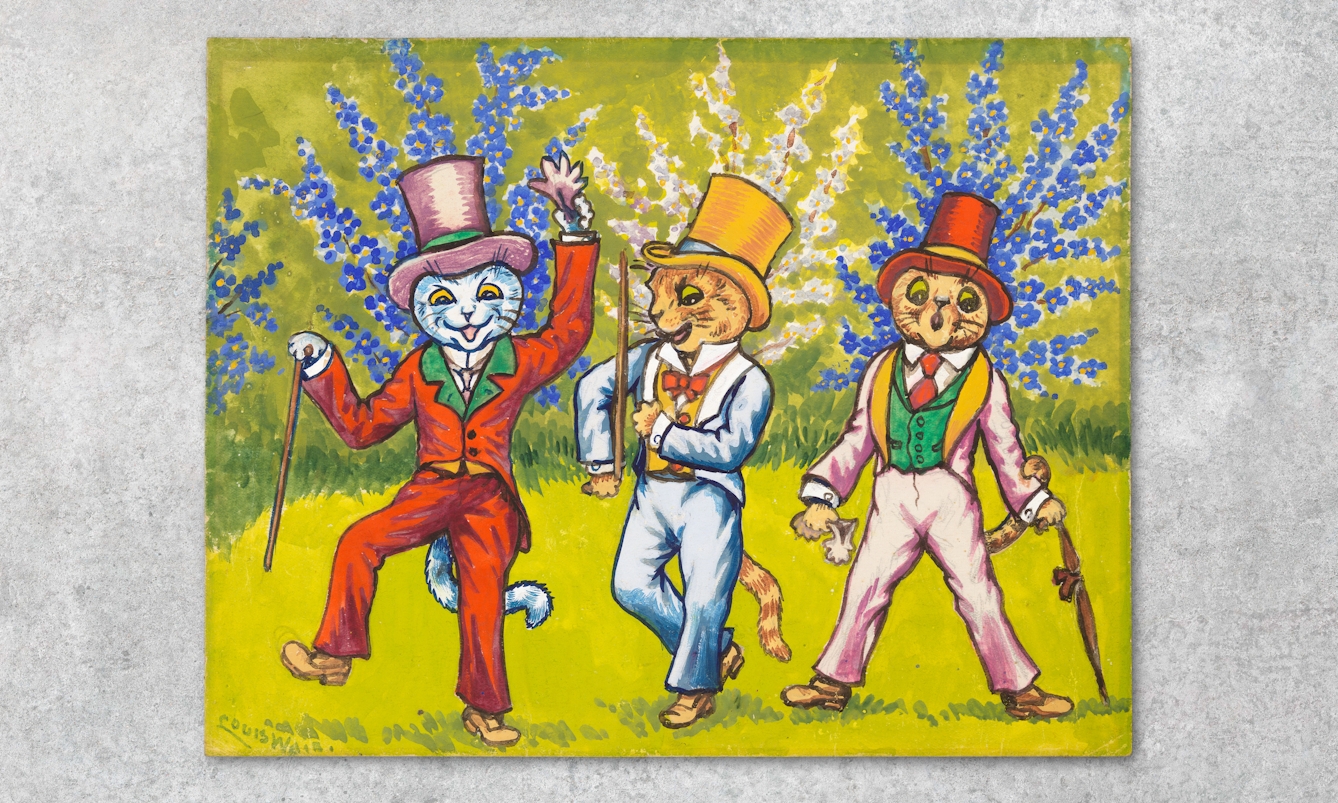

Three cats performing a song and dance act. Gouache by Louis Wain, 1925/1939. Wellcome Library(view in catalogue).

He was certainly uniquely attuned to the energy of cats, having witnessed how much comfort their cat Peter had brought to his wife Emily as she died of cancer, just three years into their marriage in 1887. Wain was also sensitive to the healing potential of art, entertaining Emily with hundreds of drawings of Peter in humorous situations and poses over the course of her illness, and continuing to derive much joy from art when faced with his own ill health in later life.

Tragedy and responsibility

Given the poverty and personal tragedies Louis Wain endured, along with the trauma of living through World War I, it is perhaps no wonder that by the 1920s Wain was struggling with depression and anxiety. He had always had a reputation for having a wild imagination, but his eccentricities started to intensify: he spent hours locked in his room, writing about a group of spirits that filled him with electricity and accusing his sisters of conspiracy, maltreatment and theft.

In 1924, struggling to cope with his behaviour, Louis Wain’s remaining family sought the help of a doctor who certified him as insane. Wain was admitted to an asylum and diagnosed as schizophrenic.

Louis Wain’s life and work deserves a wide-ranging interpretation that stretches far beyond ‘psychotic’ or ‘tortured artist’.

There are several different theories surrounding this diagnosis. As a child Wain had experienced terrifying and recurring vivid nightmares, and at school he was a dreamer, often playing truant to ramble the streets of London in an endless search for the great unknown.

In pictures

Mosaic inspired by Louis Wain made by the community in association with Willesden Green's Town Team, designed by Debra Collis, 2014.

A cat in ‘Gothic’ style. Gouache by Louis Wain, 1925/1939. Wellcome Library(view in catalogue).

The young, quiet and sensitive Wain struggled with the responsibility of supporting his mother and five unmarried sisters, as well as his new wife, after his father died suddenly when he was just 20 years old. He was both hopeless at bargaining and incredibly generous with his talent, giving away drawings to anyone who asked. Consequently, money was always in short supply.

One popular theory today is that had Wain been alive in the 21st century, he would likely have been diagnosed as being on the autistic spectrum. However, the work of psychiatrist Dr Walter Maclay helped to secure Wain’s reputation as a schizophrenic artist for much of the 20th century.

Creating the ‘Kaleidoscope Cats’

Maclay collected the work of artists suffering with mental illness and in 1939 he came across eight pictures by Louis Wain in a shop, which he arranged in an assumed chronological order to demonstrate the progression of the schizophrenic mind. His theory was that as the sequence of cat illustrations became more fragmented, so too had the artist’s mental state deteriorated.

Despite the fact that there was no evidence to support this ordering, the series of drawings, now known as ‘Kaleidoscope Cats’, became a popular visual example of the schizophrenic mind. Long gone was the Edwardian interpretation of Wain’s work as ‘charming’ and ‘humorous’. Instead, his art was often presented as ‘psychotic’ or ‘disturbed’, both words used in a major exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in 1972.

In pictures

Left, ‘Kaleidoscope Cats III’. Right, ‘Kaleidoscope Cats IV’. © Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

Left, ‘Kaleidoscope Cats VII’. © Bethlem Museum of the Mind. Right, A cat standing on its hind legs, formed by patterns supposed to be in the ‘Early Greek’ style. Gouache by Louis Wain, 1925/1939. Wellcome Library(view in catalogue).

The ‘Kaleidoscope Cats’ concept does not allow space to acknowledge or appreciate the natural evolution of Wain’s artistic practice, nor does it reflect the complexity of his personality and life experiences. Much like his cats, which could be cheeky, dark, witty, charming, vulnerable, sweet, silly, wonderfully bizarre and more, Louis Wain’s life and work deserves a wide-ranging interpretation that stretches far beyond ‘psychotic’ or ‘tortured artist’.

Perhaps, rather than representing an internal psychosis, cats disintegrating into pattern or transforming into three-dimensional Cubist designs demonstrated something positive. This could be an increasing creative confidence, evidence of enjoying new techniques, or expressing something about the radically changing world in which the artist found himself.

Imagination, genius and the sublime

Wain’s vibrant use of pattern is sublime; was it a means of exploring a lifelong fascination with electrical currents or could his more elaborate patterning have been influenced by his textile-designer mother? Or might he, as a patient on a hospital ward, simply have found the act of painting and drawing patterns soothing or meditative?

Wain’s friend Collingwood Ingram, an ornithologist and plant collector, thought of him as “an example of the thin borderline between genius and insanity, and in his way, he was a genius”. Wain certainly lived an extraordinary life, suffering great loss yet bringing great pleasure to so many in his lifetime. Whatever illness he experienced, he clearly did not ‘lose himself’ in it: his love for cats and his unique artistic ability remained strong throughout his time in hospital.

The body of work he left behind bears witness to what art collector Gustave Tuck saw as “the enormous range of his imagination, to his love of the droll and the bizarre, and to his infinite search into the lighter side of human life”. Hopefully, this year’s film will go some way to rebalancing his legacy as artist, offering a more nuanced interpretation of Wain's fascinating life and work.