It was on a day much like today, an unexceptional, ordinary day, that three little words changed everything. They even changed who I was.

Ten years ago, I sat in front of yet another neurologist, having lived in a state of suspended identity since being unofficially diagnosed a few weeks earlier. This was following a year of fruitless investigation into my complaints that my fingers ‘weren’t right’. I had been a professional guitar player, so was sensitive to change.

Today, however, it was the real deal. The tests were in. The consultation began with an explanation of the therapy the neurologist was going to start me on. “So I definitely have Parkinson’s?” I said. Her reply? “Oh, didn’t I say?”

“Well,” she said. “You have Parkinson’s.” When finally uttered, those three words first expanded to fill all the available space in my head, and then the whole of my being. I was exactly the same person as I was when I walked into the consultation room but also totally different. No longer an individual with stiff shoulders and dodgy fingers, I was now a set of symptoms. I turned from person to patient in a flash.

Early onset Parkinson's symptoms

Parkinson’s is a progressive, degenerative neurological condition that is, as yet, incurable. It occurs when the cells in the brain responsible for producing dopamine decide, for reasons best known to themselves, to die off. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter involved primarily in movement, and in the risk/reward cycle. The symptoms are many and varied, but include the classic bilateral tremor, a shuffling gait and stiffness, especially in the shoulders and neck. Parkinson’s is, primarily, a disease of diminution. It shrinks the space you occupy both physically and emotionally.

When I told people about my diagnosis, their responses were often asinine. I lost count of how many mouthed the words, “But you don’t look ill”. Perhaps the most idiotic was, “It’s very mild, then”. What they responded to was their cognitive dissonance: I was giving them a new interpretation of me that they couldn’t see. But I could see it in their faces. Parkinson’s scares people, but it’s not a death sentence. It’s more insidious than that.

When first diagnosed, most of us aren’t obviously ill. We may be a little stiff, a little slow, a little shaky, and we may struggle a little too much with everyday actions such as doing up buttons or tying our shoelaces, but we don’t actually look unwell. Add to that the fact that Parkinson’s isn’t the first disease that comes to mind when considering a physically fit, active 40-year-old man (such as I was when diagnosed), and it’s hard not to feel that we are frauds.

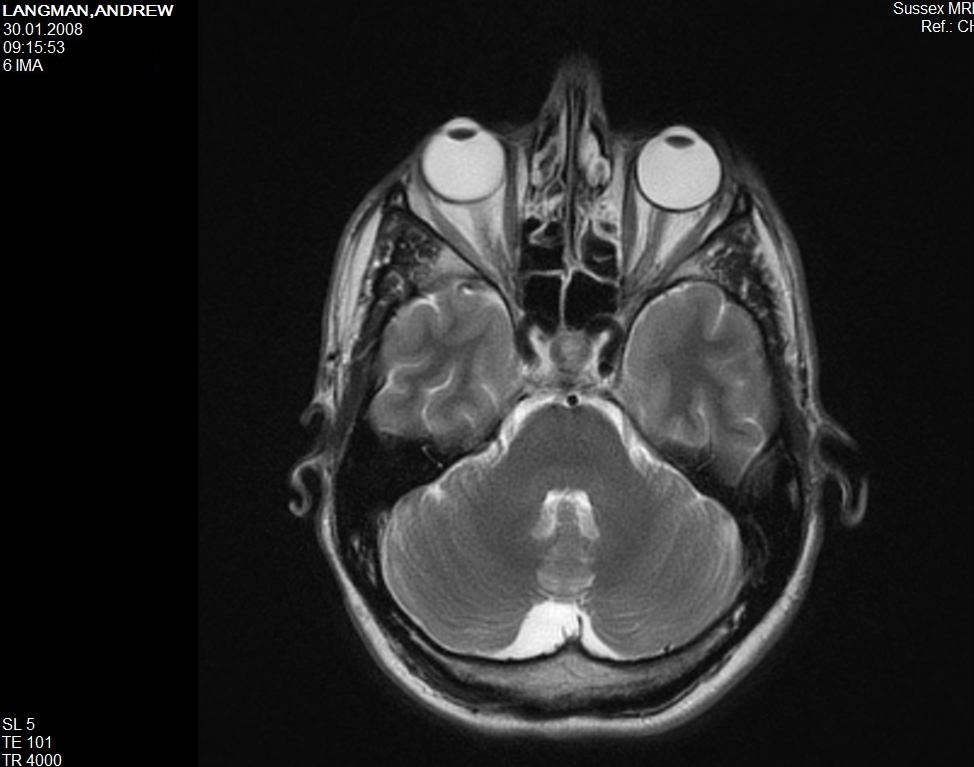

An MRI scan of Pete’s brain.

Invisibly conspicuous

Parkinson’s, especially young-onset Parkinson’s (when diagnosis is before the age of 40, or 50, depending on who you read), is a strangely visible invisible disability. While stiffness, rigidity and a shuffling gait may seem reasonable for someone in their 70s, when you see someone like me struggling to pack my bags at the supermarket, almost falling when trying to start walking, or shuffling along, perhaps bumping into door frames as I go, it is difficult not to infer a self-administered cause.

You will spend a long time looking for a young Parky who hasn’t been accused of being drunk, or been eyed suspiciously by doormen, waiters, shop assistants or bus drivers as they try to decide whether we’re “on something”. Or one who hasn’t been stared at in the street, laughed at. Abused.

While we understand this, it is impossible not to feel the heat of the glances, the stares, the unsaid opprobrium and think of it as anything other than judgement. It is an irony of the most perverse kind that at first no one thinks we’re ill, but when our symptoms manifest, still no one thinks we’re ill. There is no sign for people to read.

But with your glances, with your judgement, our disability increases. Our symptoms, especially the ‘classic’ tremor, worsen on exposure to adrenaline and cortisol. Young-onset Parkinson’s may be invisible, but its effects are not.

Difficulties and opportunities

Parkinson’s has changed my life in several senses, and not all for the worse (though don’t think for a second that it’s ‘the best thing that ever happened to me’). It makes life more difficult, day-to-day. I need to be more conscious of my general health and fitness than before, and it interferes terribly with my leisure activities – cricket especially.

But it has presented me with ambitions and opportunities I did not know existed. I have written two books because of Parkinson’s: ‘Slender Threads’ and ‘The Country House Cricketer’. I have found a community of like-minded individuals who want to make a difference. Somehow. I take some parts of life far less seriously than I once did, and grab the rest with both hands. I very much wish to feel alive while I still can. I sense, perhaps, the privilege of life in a way that once I did not.

For me, its real impact is not the stiffness, the tremor, the loss of fine motor control, the fatigue, the way that it makes me walk, or, indeed, any other of its myriad irritations. The real kicker is the way in which it gradually but inexorably separates body from mind.

The very moment of diagnosis plunges us into a binary world with infinite shades of grey. This disease of contradictions renders us invisible yet conspicuous, ably disabled, shakily stationary. It gradually erases the parts that make us unique while making it impossible for us to be seen as anything but the disease.

The changing map of the self

Parkinson’s doesn’t merely redraw us in the eyes of others; it gradually erases our map of the self. It changes our voice, facial expressions, our movements, our senses: those physical attributes through which we once asserted ourselves. Its symptoms take up more and more of our time. Just as we appear as a manifestation of Parkinson’s from the outside, so it gradually emerges from the inside. We watch ourselves as the shaking palsy becomes all people see in us, and in all that we do.

Eventually, we fall prey to a crushing sense of auto-alienation.

Today, I caught a glimpse of someone, in a shop window, with Parkinson’s: I did not see me. And it hurt.

Parkinson’s hangs over you like the sword of Damocles, gradually transforming everything. We can live perfectly well with it for years, keeping its worst effects at bay with exercise, medication and, often, sheer bloody-mindedness. But underneath, it creeps ever onwards. We know that, sooner or later, it will have its say.

About the contributors

Pete Langman

Dr Pete Langman is a writer, editor, educator, academic, ex-professional guitarist and extremely amateur cricketer. He was diagnosed with Young Onset Parkinson’s in 2008. The author of ‘Slender Threads: a young person’s guide to Parkinson’s Disease’ and ‘The Country House Cricketer: an English summer in words and pictures’, his words have appeared everywhere from Guitar and Bass Magazine to The Guardian. His first novel, ‘Killing Beauties’, will be published on 23 January 2020 by Unbound.