Memories of childhood trips to the beach are all the more precious to poet and author Penny Pepper because her father was there. In his short life he encouraged her to explore nature and the sea, fostering an appreciation of the natural world that became an invaluable resource to her as she grew up.

Nature’s presence lives in the atmosphere at Pett Level Beach, between Hastings and Rye on England’s East Sussex coast. It’s an entity in its own right – heavy with a desolate ambience, broken by the constant voice of the wind, gulls riding the thermals and seaweeds of many kinds bringing distinctive, briny smells.

I love the path, mostly usable by wheelchair, because it’s smooth with few obstacles, and because it runs parallel to the beach. Typical shingle, baked in sun, details of alien sea cabbage adding to the uneasy expanse.

This beach pleases itself, unforgiving with its stones and faraway tide. My wheelchair can’t wheel on it, of course, but it doesn’t matter when the sun is high overhead and my little feet rest naked on the warm surface, toes sensing the shapes of the pebbles as I dream of finding fossils and hagstones.

Hagstones are the ones with holes right through them. They’re a regular feature on all shingle beaches, and I often ask friends to track them down. Enjoyed through millennia, the hagstone is lucky and protects you from evil.

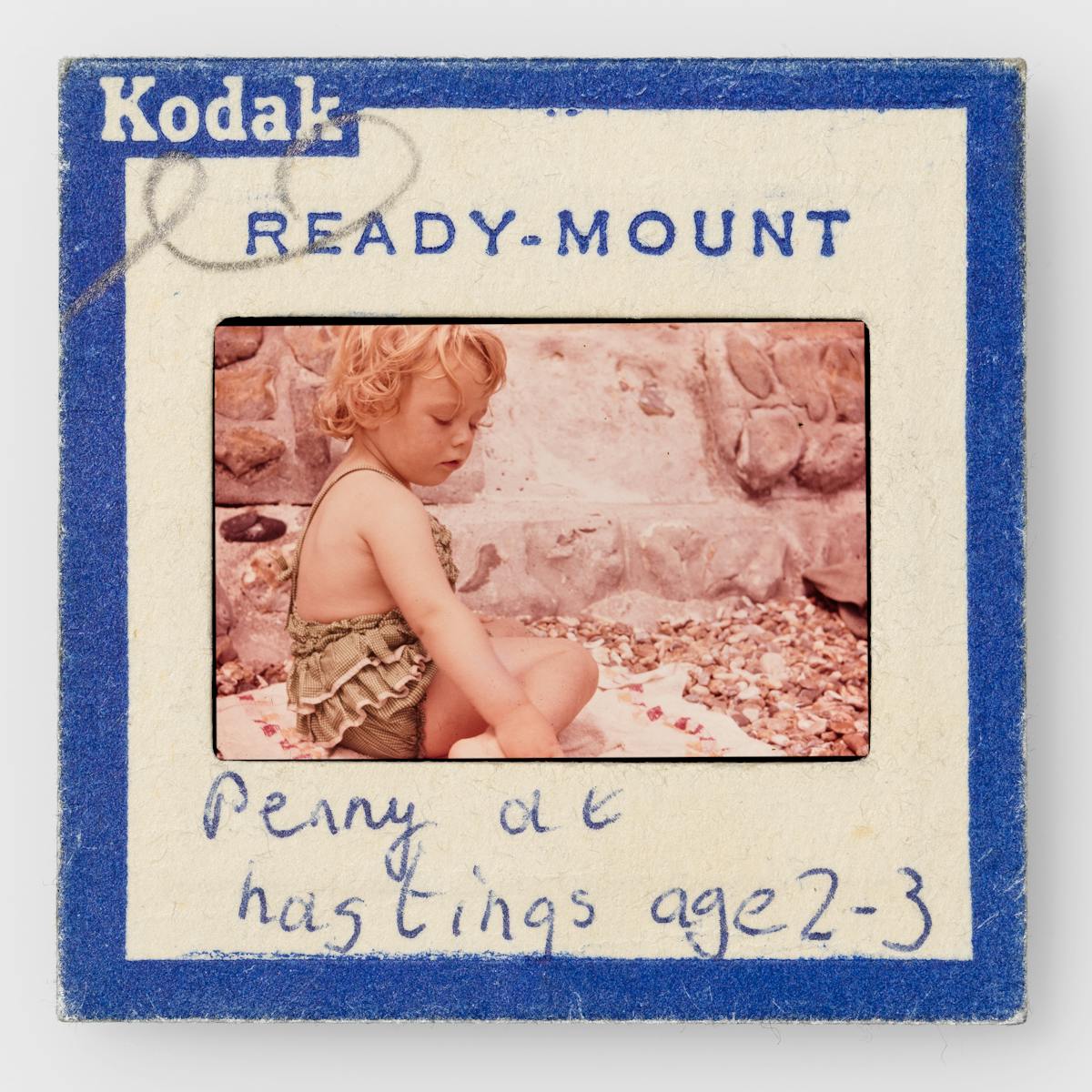

Top row: Family holiday in Hastings, 1964/5. Bottom row: Family holiday in Cornwall, 1965.

Aleister Crowley, notorious 20th-century occultist and brief Hastings local, cursed the town with his usual impish humour by proclaiming that those who come to Hastings cannot escape it unless they have a hagstone tied in their window. But the irony is that there’s an alluring spell cast by these ancient seaside towns which, in my case, means I never want to leave.

Such occasions remind me that nature has had a presence in my life since childhood, growing up in a semi-rural setting. There was always a wood, a pond and birdsong, and I never felt a separation from the natural world. It never needed to be forced upon me. It’s simply there, available to me as a reassuring place, away from a life of imposed constraint.

Seaside memories

I first visited Hastings beach when I was four years old, my father making up games that were gently educational. Inheriting his innate curiosity, I lapped up these pursuits, which also bypassed the reality that I was not medically permitted to walk.

The command to rest was a tedium in my childhood. Clever Dad distracted me, organising pebbles into colours and shapes, and competitions with my brother about how far we could throw them. Paddling in the sea was encouraged, and I didn’t complain it was cold or frightening. The transparencies from Dad’s photographic collection show me in a dream, inside a rubber ring, splashing at the waves.

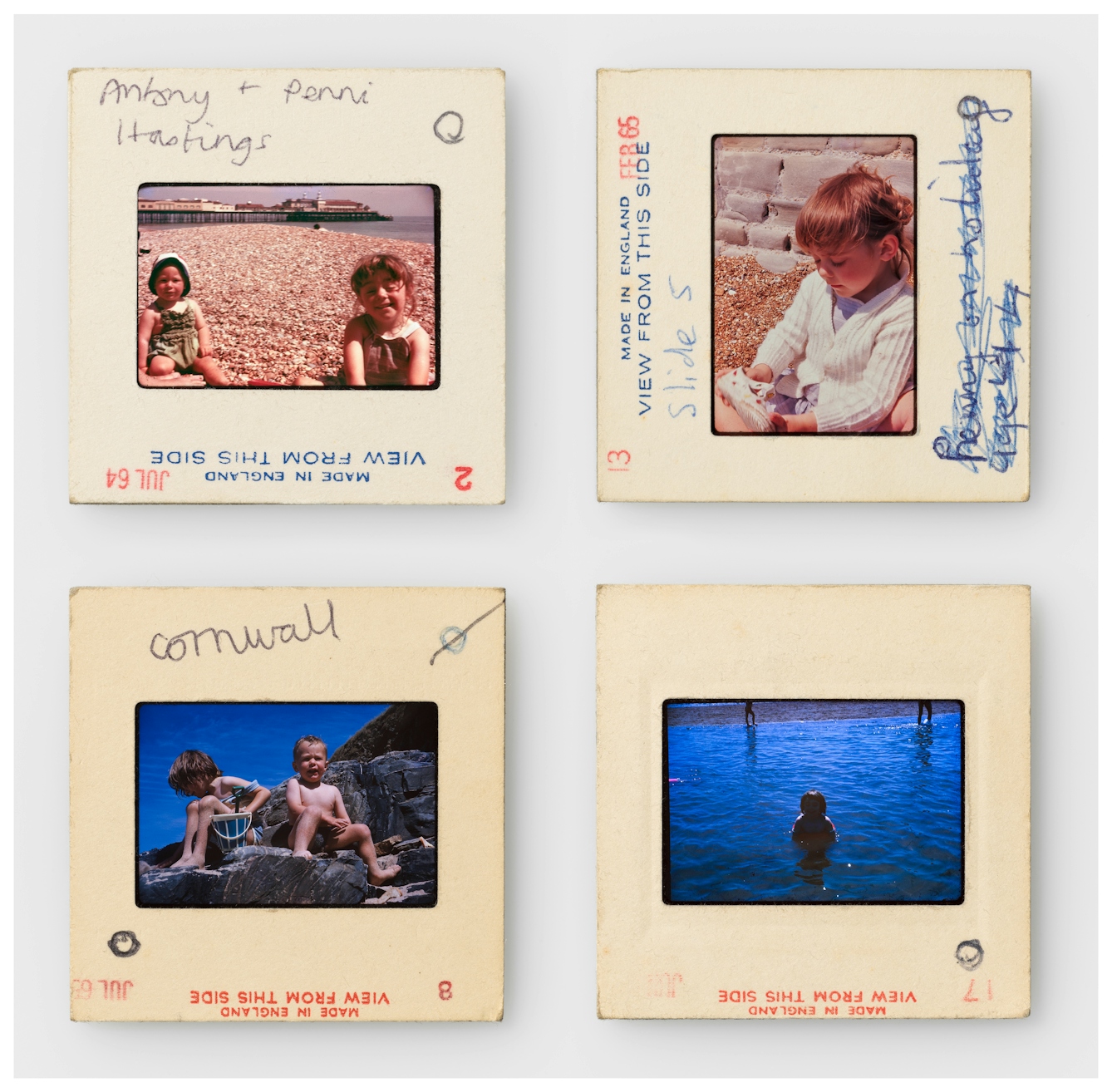

Left: Penny holding a small bird, 1965. Right: Penny in the garden, 1965.

I didn’t have Dad for many years. But those I did fired up the reason for my love affair with nature.

There’s another photograph of me holding a sparrow in the palm of my hand. I’m around seven, looking down at the little bird with a soft smile. I remember the tremble of its tiny body and my wonder at how it felt almost weightless. Those were days of summer sun on salty-aired beaches, fresh green parks and open countryside redolent of the many visited and the anticipation of those times to come.

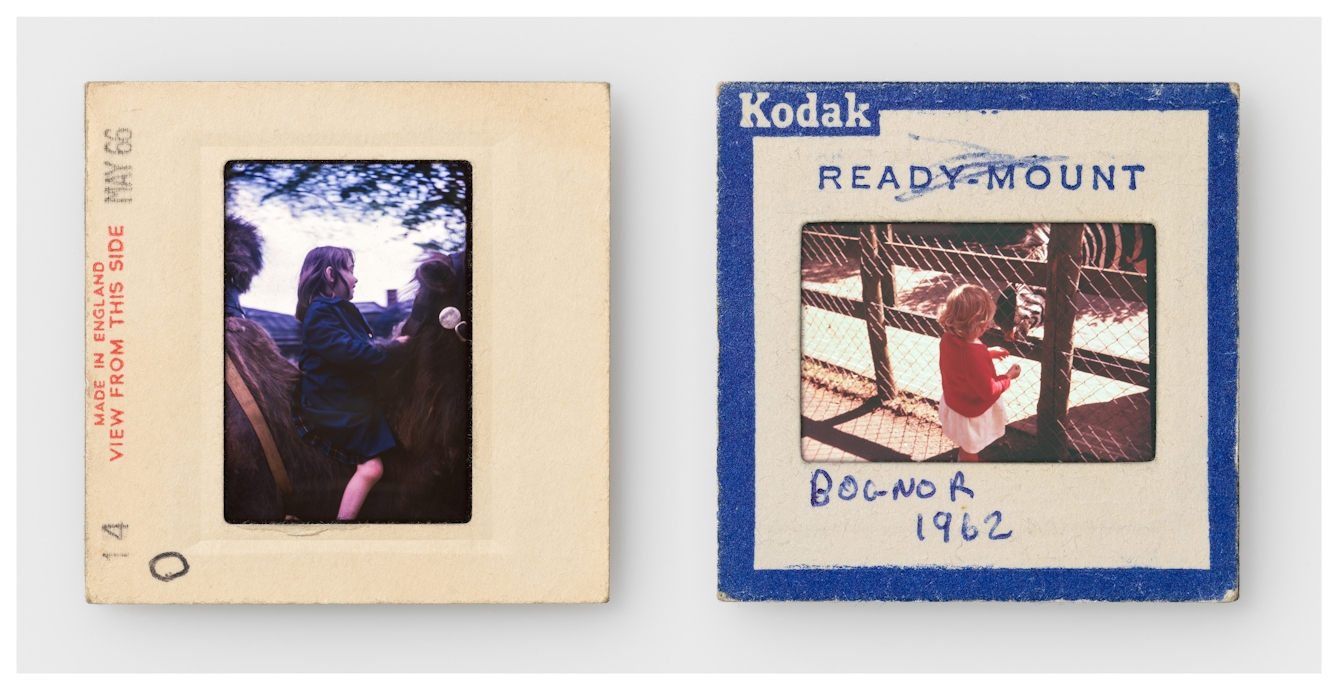

As I was unable to stand for long, Dad held me up to let me relax into the powerful winds on Lizard Point, Cornwall, with his arms wrapped securely around my waist. There were camel rides, donkey rides, goats to feed, ponies to stroke.

Nature was a constant as I burgeoned into a poet, the inconstancy of chronic illness tempered as a result.

Left: Penny riding a camel, 1966. Right: Penny with a zebra in Bognor, 1962.

In the rural Chilterns, he taught me connections to everything in the natural world. Sitting on his knee by the little stream in Latimer, spotting sticklebacks.

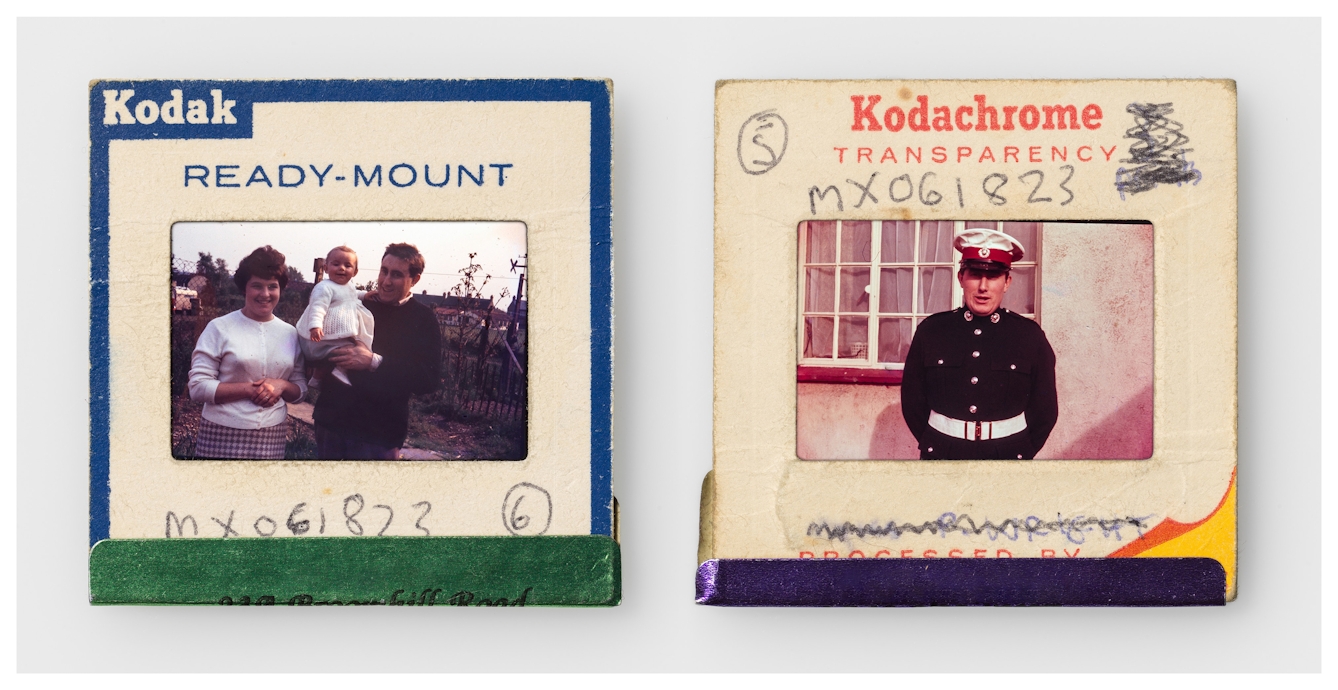

Dad didn’t see me in a wheelchair. Only those times at the hospital, from X-ray to consultant, when its use was inevitable. He died when I was seven and he was 29. Nothing prepares a child for such an unexpected culling. For a while there was nothing, and no amount of sunshine days, dandelion-seed clocks and daisy chains made by my mother would console me – or her.

Nature was a constant as I burgeoned into a poet, the inconstancy of chronic illness tempered as a result. My adolescence was spent in a rehabilitation hospital placed in the depths of woodland, not far from Burnham Beeches in Buckinghamshire. These days a national nature reserve and an SSSI (Site of Special Scientific Interest), recollection is stirred every autumn by the soft smell of damp leaves. From my wheelchair, it was a thrill to kick my feet through the beautiful rust-coloured piles, nervous yet hopeful I would wake up some hidden sprite and take inspiration back to a juvenile poem.

In spring we were spoiled by bluebells, their sharp scent dancing through the April air as teachers told us we shouldn’t pick them. These days I’m thankful to find a huge spread where there may be a wheelchair-accessible path – and East Sussex doesn’t disappoint.

During this time, nature formed part of my healing processes, particularly for my frayed emotions. Yet I also realised, as I grew up, that same nature, in the form of our own biology, could never be perfect and was the reason for my father’s death. A random breakdown in physiology. The natural world’s consolation would come, but it could take an entire lifetime.

Penny, Leytonstone, 1985.

How nature defines the city

The chaotic nature of my life dragged me into adulthood, decisions always questioned and others imposing them. At first, an eventual relocation to London challenged my necessary relationship with nature. But there were always the urban foxes and feral pigeons, their gorgeous iridescent necks flashing in the light as they picked over our waste.

I soon adapted to nature in this urban setting, its tenacity to flower and flourish – the doggedness of those dandelions, the cement-cracking array of weeds and erupting tree roots that would not be denied. Even if, as a wheelchair user, they were something of a pain.

Gabriel, a soulmate with nature and travel, was equally committed to explorations, with some wilfulness that occasionally veered into danger. I’ve held a tarantula in my palm, had a boa constrictor around my shoulders at a tropical animal sanctuary and, better still, seen the native adder at Goonhilly, Cornwall.

I did an unplanned somersault from my wheelchair on a nature reserve, and we have both had our wheelchairs stuck in the mud many times. I sympathise with nervous officials, if present, but remain obstinate that it’s my right to take risks to see beauty, bright and challenging.

Left: Penny with mother, Shirley, and father, Michael. Right: Penny’s father, Michael, Royal Marines Reserve.

Last year I watched the Perseids, counted collared doves on my feeders and sat in my wheelchair as near as I could get to the highest point in southern England – the majestic Dunkery Beacon, where the voice of wilderness speaks through the wind across the austere beauty of Exmoor.

I now live on the coast, and there’s a feast of nature everywhere. I can follow the lure of the wood and the call of the sea with a satisfying balance.

My father lives on as a dream from the times he grounded me in my respect for the natural world, and I wonder what Dad would say if he knew how much our summer beach days gave me. I like to think he’d be proud and eager to hear my poem ‘Supermoon at Swanage Bay’,

“Waves shiver,

a frisson response

towards your soft yellow face

noting the tides,

keeping nightmare tsunamis

away.”

I think of my dad as I wheel along the path of Pett Level Beach, with its unmistakable smell brought in by the languid sea, which I know he would love as much as I do. While I still count pebbles, look for hagstones, I stay confident that I will always find the pathway to the natural world that is right for me.

About the author

Penny Pepper

Penny Pepper is an award-winning author and poet whose fiction pushes the neglected disability narrative. Her memoir, ‘First in the World Somewhere’, was published in 2017; her poetry collection, ‘Come Home Alive’, in 2019. Other work appears in Hemingway Shorts 2021, Mslexia and Byline Times, while her novel, ’Nancy Jones and the Show of Wonders’, awaits a publisher.