The last year has brought mental health inequalities in the UK into plain sight. Writer and campaigner James Downs argues that it’s possible to build a mental healthcare system to support everyone in need.

Over the last year our lives have been dominated by a new and existential threat to our physical health. In social and economic terms too, society has reeled from the massive repercussions of the coronavirus pandemic – an impact that hasn’t been equally distributed. Initial proclamations of collective solidarity slowly gave way to a recognition that the statistics around who was most likely to be impacted told a very different story.

Across age, gender, ethnicity, wealth, housing and more, the idea that “this virus does not discriminate” has been proven untrue, with some facing far greater difficulty, risk and uncertainty than others. The threat of coronavirus has turned out to be as much about our problems as a society as it is about a new pathogen. Inequality, it seems, is far from asymptomatic.

It’s not harm-free to sit on a waiting list or be told that your problems aren’t serious enough to qualify for treatment.

The mental health impacts of coronavirus are no different in being unequally distributed. Nor are they separable from the physical and economic impacts of the pandemic. It’s no surprise, then, that many of us already struggling with mental health problems before coronavirus may have found it even harder to cope with lockdown restrictions.

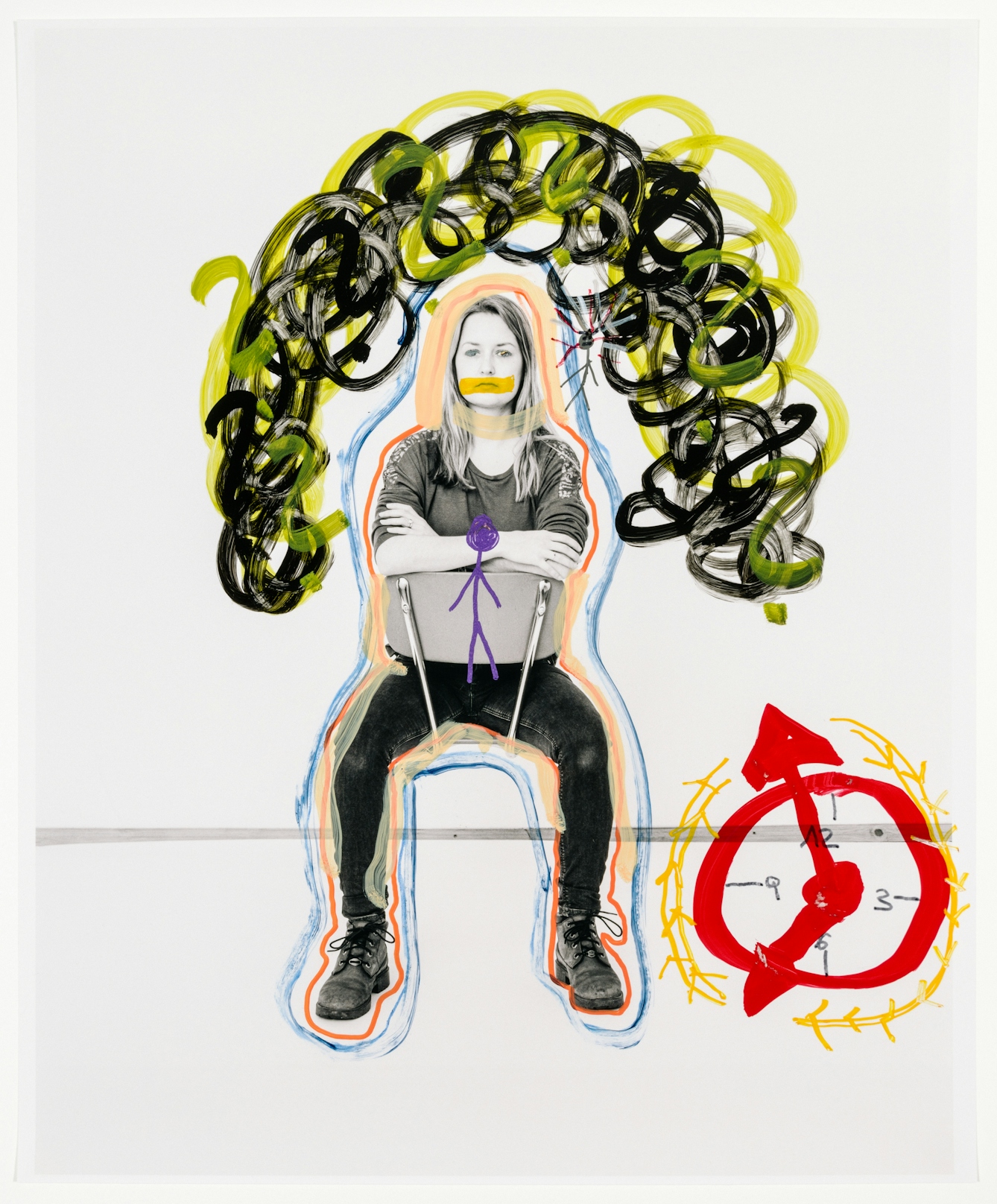

Sara: “For me, it is like this. If something is not going well elsewhere, I start being very focused on myself, on how I look, that I can’t stand myself, that I can’t stand my body. Therefore I try to control everything, but in the last few months and in the last year, it has become worse. It always needs more energy for me to not give up.”

In my work in mental health policy, patients have often told me that their access to pre-existing support was limited or changed in ways that negatively impacted their mental health. Clinicians have also described how, during the first lockdown, there was a sudden and alarming increase in people presenting with severe psychiatric symptoms for the first time.

How well equipped we were to respond to any of the impacts of coronavirus was in part predetermined by how healthy our response systems were beforehand. In the case of mental health, entrenched inequalities and gaps in service provision were well established long before the pandemic reached our shores. I’ve seen first-hand what it means to be in systems that cannot meet you with the right support when you need it.

A system with harm built in

When I developed anorexia as a teenager, I was already in child and adolescent mental health services – ideally situated for early intervention. But the system I found myself in was ill-equipped to help me and failed to recognise that eating difficulties could happen to males too. As a result it was over six years before I was able to access specialist psychological treatment.

By this stage not only were my difficulties more entrenched, but I’d also suffered a desperately poor quality of life. This story is not uncommon, but action is still needed years later if we are to prevent others sharing the same experiences as me today.

Elias: “If I cannot make music with my bandmates, I do not have the motivation to sit at home and write something. For a year I have barely done anything musically and have noticed how this coping mechanism is missing. I have also noticed how I have gone back to certain patterns, to when I felt very bad and the eating disorder was worse, to playing for hours on the computer and delaying the time to eat.”

While the quality of support you can access matters, it’s also true that far too often no support is available at all. In the case of eating disorders, I’ve seen from both sides of the patient/policy divide that thresholds for accessing treatment are so high that even very unwell people are left with little to no support.

With severe anorexia I was told I was “too underweight to engage with treatment”, and to come back to services when I’d miraculously done the initial stages of recovery without help. Years later, with bulimia, I was told I was “too medically stable” and “not underweight enough” to be seen as an outpatient, despite multiple admissions to hospital for physical complications and suicide attempts during the period when I was denied treatment.

Not being able to receive healthcare when you need it is not a neutral thing. Underpinning the whole of medicine is the principle of “doing no harm”, yet in the field of mental health, our current systems have the potential for harm built in. It’s not harm-free to sit on a waiting list or be told that your problems aren’t serious enough to qualify for treatment.

As an eating-disorder patient, I’ve only been able to reliably get treatment for the physical aspects of my condition. This bias towards physical health and against mental health is predetermined at a structural level.

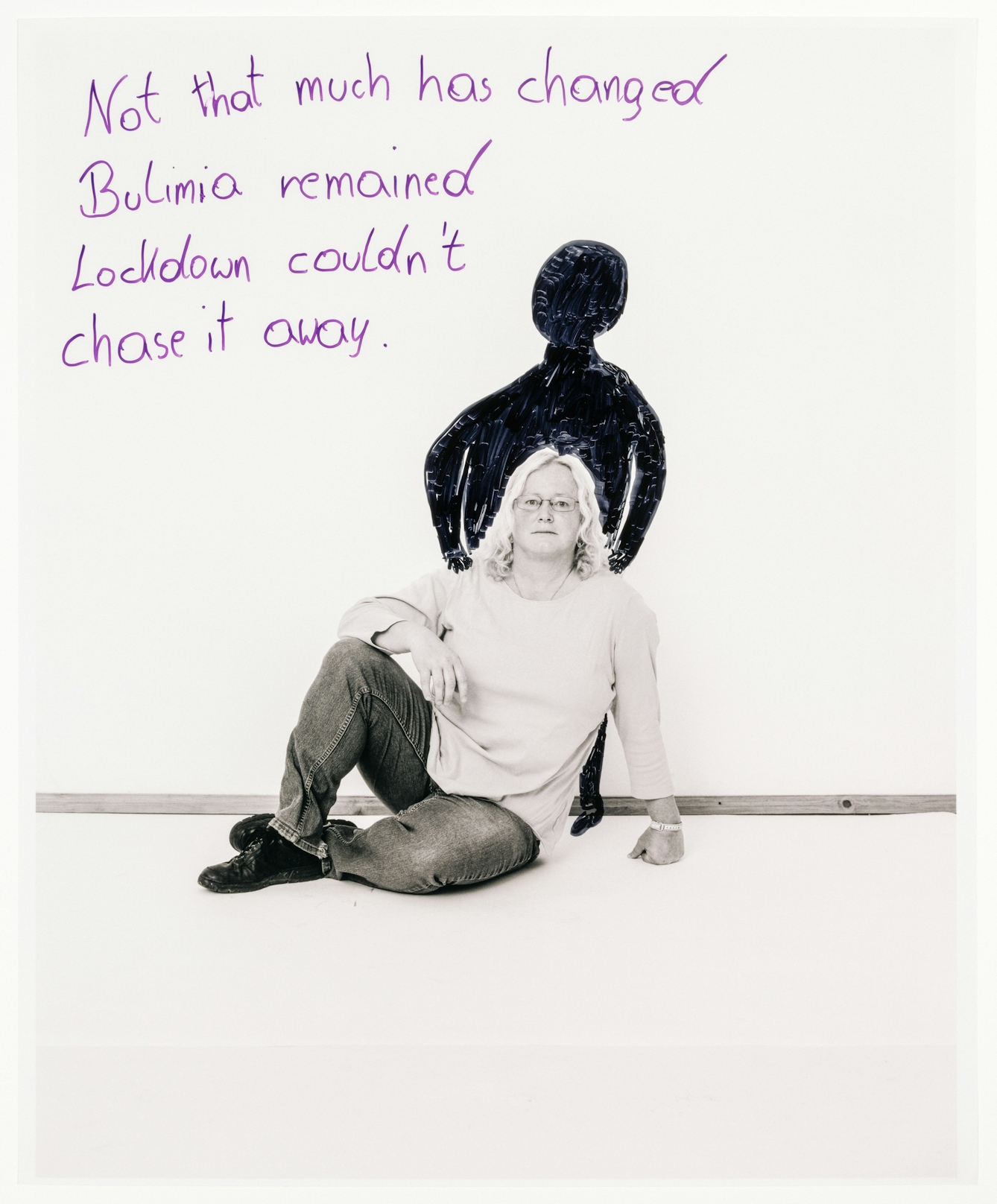

Manuela: “The first lockdown, I must say, was much harder for me. Two of my four children still lived at home and were very strict with me. They knew about my eating disorder and had complete control over me. They did not let me binge eat or vomit. Sometimes I had to go for a walk to throw up in the forest. Yet, for me, it is more the past that really burdens me than the pandemic.”

A sector that lags behind

We invest comparatively little money into research developing understanding and treatments of mental health problems, which have similar prevalence rates to well-funded, clearly understood and widely treated physiological conditions.

Despite mental health problems accounting for 23 per cent of the burden of disease in the United Kingdom, mental health placements are not a compulsory part of doctors’ training, and spending on mental health services constitutes only 11 per cent of the NHS budget.

The only increase in NHS mental health spending beyond what was already planned before coronavirus is £500m – around £7.50 per person – to commence from April 2021, over a year after the first lockdown. Contrast this with the ready outpouring of resources to deal with the existential physical threat of a new virus and the challenges to our economic health posed by lockdown restrictions.

Professionals I work with tell me how worried they are that systemic problems in access to treatment aren’t just slow to improve – they are becoming more acute after a year in which demand has risen and provision has been restricted.

Flora: “I have enjoyed more stability now than before, so something continuous. I have got to the point that I can steer the wheel alone. Sure, it is always hard and a constant fight against myself, but I have noticed that I do not have to expect any sort of relationship or any kind of story to give me the feeling that I am allowed to feel good.”

The possibility of positive change

We often say, “It’s OK not to be OK.” But if you’ve ended up in such isolation and distress during lockdown that the only place of safety is A&E, is that really OK? Is it OK to live with such poor mental health that your quality of life is limited, yet you still somehow don’t qualify for treatment? These things certainly don’t feel OK.

When it comes to coping with and seeking out help for our mental health, we seem to put all of the responsibility in the court of the person who is already struggling. But the reality is that it’s only OK not to be OK when the relationships and systems around you can hold you when you’re unable to hold yourself. At the moment, too many are left unsupported, uncared for and with their fundamental mental health needs unmet.

But this can change, and there is hope.

However individualistic our society, we must never underestimate the power of our relationships, our social environments and our institutions as vehicles for positive change. The task of making mental healthcare more equitable and accessible for all involves examining and improving the structures that surround mental healthcare.

Listening to people’s experiences of their mental health before, during and after the pandemic should be at the heart of creating the meaningful change we need. Only when we have built a mental healthcare system that is guaranteed to be there for us when we need it – whether in a global pandemic or in the struggles of our everyday lives – will it be OK not to be OK.

And only when we have closed the gaps that have long existed in the way we treat mental health will we be able to say with confidence that we really are “all in this together”.

About the contributors

James Downs

James is a mental health campaigner, peer researcher and expert by experience in eating disorders. He holds various roles at the Royal College of Psychiatrists and NHS England aimed at improving support for those experiencing mental health problems and eating disorders, and for their carers. James also represents various UK mental health charities.

Mafalda Rakoš

Mafalda is a visual artist based between Amsterdam and Vienna. Her practice moves along the intersections between art, anthropology and documentary photography. This has resulted in a series of books, exhibitions and editorial contributions. For eight years she has been developing a body of work around eating disorders through different media. Having been formerly affected herself, she has been analysing whether these projects operate with, for, or about the persons involved in them. Her working process requires time, trust and many conversations. It serves as an invitation to dive more deeply into the hidden layers to create a bigger picture around the heart of the matter.