Why did they pick that topic, and what are the best stories within? The exhibition's curators open up.

Inside the minds of Teeth’s two curators, James Peto and Emily Scott-Dearing

Words by Gwendolyn Smith

- Interview

One of the first objects you’ll encounter at Wellcome Collection’s ‘Teeth’ exhibition is a barber-surgeon’s chair, but not the kind of slick leather dentist's chair you might be ushered into today.

This 19th-century specimen is wrought from uncomfortable-looking oak, and the three-pronged, claw-like headrest seems even more menacing when it dawns that the seat was not just used for hairdressing but also for ‘tooth-pulling’ in days of yore.

“You can imagine having to tip your head back into the terrifying headrest waiting for someone with a pair of pliers to loom over you – it paints a very vivid picture,” says Emily Scott-Dearing, one of the show’s curators.

It is this visceral relatability that makes the exhibition’s subject so fruitful. As Scott-Dearing notes, teeth hold a significance that goes beyond their physical prominence. Yes, they are the only exposed part of the skeleton. But our gnashers are also key in marking personal milestones (think tooth-wobbling, the Tooth Fairy and wisdom teeth). They’re indicators of wealth or a lack thereof (Hollywood smiles versus crooked grins), and they enable us to literally taste the world via eating.

“You can imagine having to tip your head back into the terrifying headrest waiting for someone with a pair of pliers to loom over you – it paints a very vivid picture,” says Emily Scott-Dearing, one of the show’s curators, of the barber-surgeon's chair.

Perhaps unsurprisingly then, Scott-Dearing and co-curator James Peto got strong responses when mentioning that they were working on the project.

“There was almost universally a split-second reaction – either raising a hand to a mouth slightly self-consciously, or the quickest of lip twitches to check you haven’t got any food stuck between your teeth,” says Scott-Dearing. Peto noted the discomfort too. “With a lot of people there’s a slight revulsion, whether that’s an anxiety about going to the dentist or a psychological thing about the idea of other people’s mouths.”

Due to this squeamish side, injecting levity into the exhibition was a top priority. When it came to the final cut “one of the key things was to not drop things that were counterbalancing the gory, harder aspects of the content,” says Scott-Dearing.

MORE: Curator Laurie Britton-Newell's inside view of ‘Somewhere in Between’

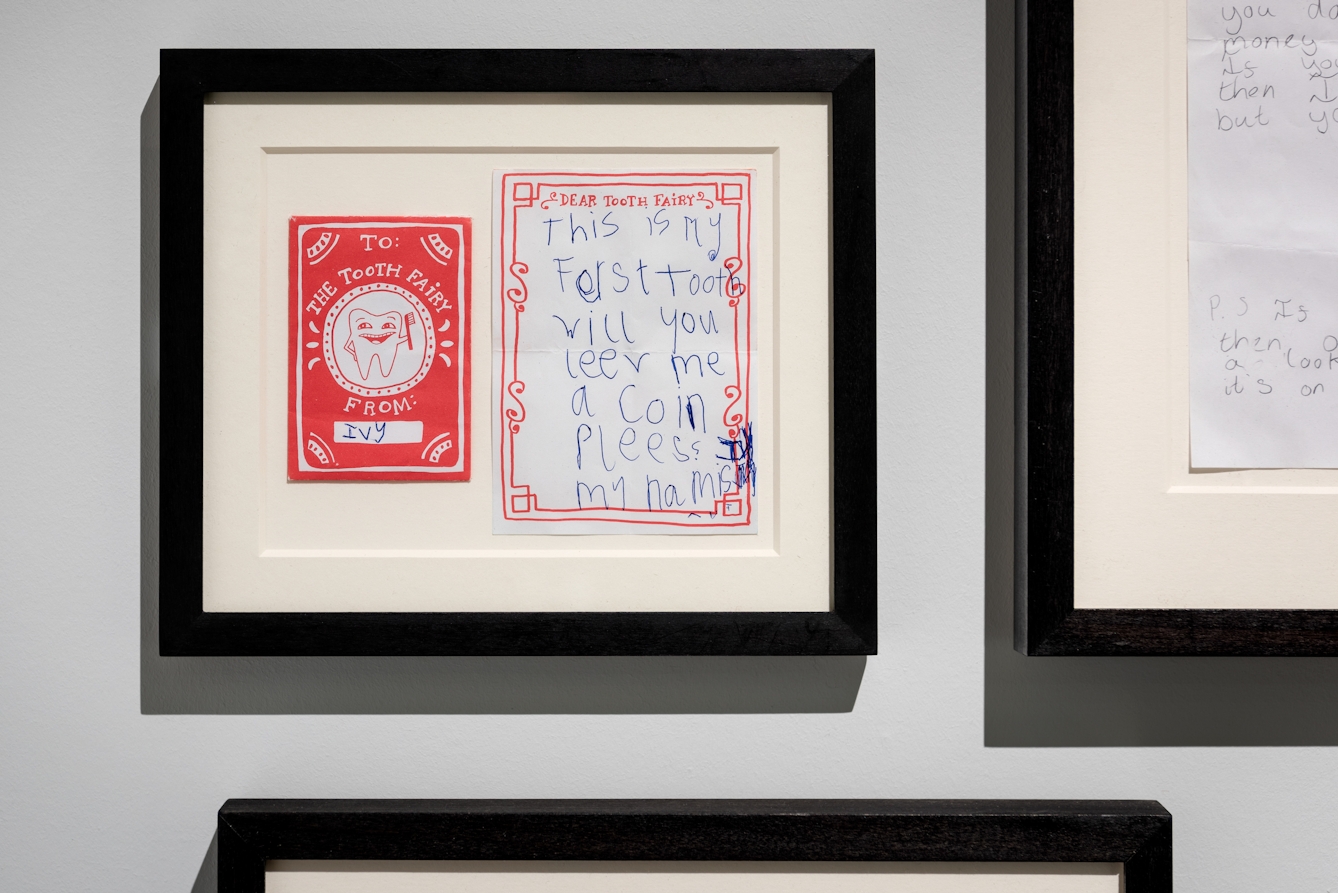

On entering the exhibition, visitors are confronted by a wall of almost laughably bossy dental care posters, while a collection of contemporary Tooth Fairy letters is guaranteed to raise a smile (albeit a newly self-conscious one). The idea for the latter came from a picture Peto had discovered that showed how Tooth Fairy payments differed across the country. Deciding that authentic missives would be more engaging than a graphic, the curators crowdsourced a selection of Tooth Fairy correspondence.

Scott-Dearing and Peto wanted to include authentic letters to and from the Tooth Fairy. This one from Ivy explains that this is her first tooth and asks politely for a coin.

Curatorial challenges

‘Teeth’ as an idea first emerged when another exhibition fell through. Wellcome Collection had just published Richard Barnett’s history of dentistry ‘The Smile Stealers’, and seeing as most of the tools and techniques illustrated in the book came from either the Science Museum or from the Wellcome Library, it seemed a promising starting point for the replacement show.

Peto worked up the idea in its initial stages, handing over to Scott-Dearing, who previously worked at the Science Museum, when he left for a research leave stint. They had a couple of months’ handover period.

Co-curation could be a battleground, but these two found it beneficial. “I really enjoy it because you can bounce ideas backwards and forwards,” says Peto.

One particular advantage arose in the editing process. Peto had written much of the exhibition’s introduction text and captions, but Scott-Dearing by and large dealt with the process of cutting it down to fit graphic design requirements. “I was just one step more removed and in the thick of very real production deadlines so it was easier for me to make decisions about that,” she explains.

Scott-Dearing's favourite object is the cockscomb with a human tooth implanted into it by Scottish surgeon John Hunter in the 1770s, which “represents extreme innovation.”

From Napoleon’s toothbrush to a panoply of dental training tools, the exhibition predominantly hinges on artefacts rather than artworks. “There was a risk that everything was mouth-sized,” admits Peto. In order to combat this, the duo tried to include different scales – such as featuring content like the phantom head teaching aid – and attain a balance between exhibits on the floor and on the walls.

Each curator has a favourite object, which perhaps epitomises their curatorial background. For Scott-Dearing, who’s curated the Science Museum's upcoming new Medicine Galleries, it’s the cockscomb with a human tooth implanted into it by Scottish surgeon John Hunter in the 1770s, which “represents extreme innovation.” Hunter was incorrect in believing he’d managed to connect the tooth root; modern examination suggests it was simply well embedded. But, Scott-Dearing says, “In an area of the exhibition where you could be thinking, ‘Gosh this is very barbaric’, it’s a reminder that in the context of those times it was sophisticated new thinking.”

The star of the show for Peto, who has worked at the Design Museum and Whitechapel Art Gallery previously, is a gilt-framed window display for a Belgian dentist from the late 19th century. “It’s showing off, saying, ‘I can give you a wonderful set of teeth.’ But if you look closely the dentures on show are really hideous things, which means it takes on the air of a surreal artwork.”

Peto gravitates to a gilt-framed window display for a Belgian dentist from the late 19th century, which "takes on the air of a surreal artwork.”

Personal and technical change

Just as a wisdom tooth sometimes has to be pulled, so do concepts from the longlist of what could be included. “It would have been interesting to go back into pre-history and have some jaws from different skulls that showed how the shape of our teeth have changed according to our diet,” says Peto. Other reluctantly jettisoned ideas were the bestial connotations of teeth, along with their vital role at mealtimes.

“I knew we had to do something that people can connect to personally,” says Peto. Scott-Dearing echoes this notion. “You need to know not only how the equipment worked but who used it, with whom, with what motivation and in what context.” Her time at the Science Museum instilled “an appetite for a judicious sprinkle of the contemporary”.

The digital dental chair at the end hints at the future of dentistry, Scott-Dearing says.

Luckily, the collections contain plenty of objects rich with personal stories. Take the prisoner of war whose dentures were smashed by a guard. Brilliantly, he got a new set wrought by a fellow inmate out of aluminium from a fallen Japanese fighter plane. “That completely lifts you out of the technical history and does something much more engaging,” says Scott-Dearing.

In ‘Teeth’, one of her and Peto’s primary goals was to illustrate the trajectory of technical change and how that has informed our experience in the dentist’s chair today. The digital dental screen towards the end of the exhibition was useful, because it enabled them to play material that hints at the future of dentistry.

Without that perspective, some of the more primitive-looking tools displayed could lead to the show painting an erroneously negative picture of the profession, Scott-Dearing says. “You need a punchline that says, ‘More change is coming. This is a journey.’”

Teeth is open until 16 September 2018 at Wellcome Collection.