Colonial botanical texts, as astonishingly beautiful as they are, may cast very dark shadows. Sita Reddy compares three works, each written roughly a century apart and under three different colonial powers in India.

In the lapis lazuli-hued rooms of the ‘Ayurvedic Man’ exhibition, you’ll find yourself in front of three botanical texts that speak volumes. Together, they define the colonial history of Indian medical botany.

Written approximately a century apart and under three different colonial powers, these three texts trace the story of Europe’s long colonial encounter with Indian botanical medicine.

- ‘Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de las Indias Orientales’ (1578) is a Spanish translation of a key Portuguese text resulting from the search for medicinal spices by the Estado da India.

- ‘Hortus Indicus Malabaricus’ (1678–1693) is an illustrated Dutch botanical work produced by the VOC (Dutch East India Company) that definitively maps Indian medico-botany for centuries to come.

- ‘A Catalogue of Indian Medicinal Plants and Drugs’ (1812) is an English compendium of useful medicines reflecting the rapid rise of economic botany under the British East India Company.

All three fall under the category of ‘herbals’ – books containing names and descriptions of plants with information on their medicinal, tonic, culinary, toxic, hallucinatory, aromatic or magical powers. But their diversity suggests that the colonial encounter with Indian materia medica was no monolith.

The title page of ‘Tractado de las drogas y medicinas de las Indias Orientales’ (1578). By Cristóbal Acosta.

Dialogues in medical botany

The Portuguese were the first to arrive on Indian shores in their attempt to control the eastern spice trade. And while Acosta’s Spanish ‘Tractados’ text was widely known in its day, we now know that it was the direct, if unacknowledged, translated copy of an earlier Portuguese text that is the real original in this botanical story: Garcia d’Orta’s ‘Colóquios dos Simples e Drogas’ (1563). Orta served as personal physician to two Portugese viceroys under the Estado da India, and later to the sultan of Ahmadnagar.

It is impossible to overstate the originality and charm of Orta’s extraordinary text. It includes 59 colloquies – or conversations – on medicinal plants arranged in semi-alphabetical order. The dialogues are between Orta himself and four other characters, including the fictional physician Ruano (literally ‘man in the street’) and Malupa, a Hindu physician.

Widely considered to be the first colonial treatise on Asian medical botany, ‘Colóquios’ was funded by the Estado da India as an indispensable catalogue of tropical medicines in their native habitat – 16th-century Europe’s introduction to Indian materia medica.

As a botanical text, ‘Colóquios’ was many things: a list of simples, a detailed outline of the medicinal properties of the spices that drove Portuguese imperialism. Limited to medical plants sold in Europe, it argued for the value of spices – not just as culinary desirables, but as miracle drugs.

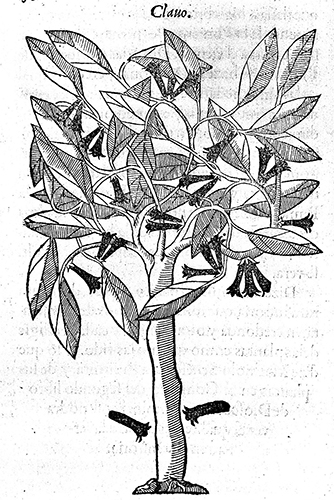

Of his encounter with the clove/cravo da India, Orta writes: “So strong and so delicious that I thought there must be a forest of flowers. It is to be used first as a medicine and for the scent, and then for culinary purposes.”

An illustration of cloves from the ‘Tractados’, 1578.

It was also a practical guide to colonial settlers on how to cope with the many illnesses of tropical India (including a classic clinical description of Asiatic cholera), and a discursive, philosophical conversation between two medical knowledge systems. “Do not frighten me with Dioscorides or Galen,” says Orta to Ruano in ‘Colóquios’, “because I am only going to tell you what I know.”

What Orta knew turned out to be: the power of empirical observation, the Indian medical practices of local Unani physicians, and the inclusion of Judeo-Islamic medical networks that would have prevailed in pre-Inquisition Spain (where he trained), as well as in the Ahmadnagar court (where he practised).

As Richard Grove suggests, Orta’s magnum opus – Europe’s first print encounter with tropical botany – led to the diffusion of Indian medico-botanical knowledge into wider European medical and commercial networks.

Frontispiece from ‘Hortus Indicus Malabaricus’ by Hendrik van Rheede, 1678–1693.

The garden of the world

If ‘Colóquios’ relied on Unani sources, the 17th-century Dutch botanical, ‘Hortus Indicus Malabaricus’, famously relied on Ayurvedic ones.

In 1678, Hendrik van Rheede, the governor of Cochin for the Dutch East India Company (VOC or Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie), began to compile the first definitive history and survey of tropical botany in South Asia.

His impetus? To find local alternative sources of medicine for their military troops, as drugs imported from Holland lost their potency during sea voyages.

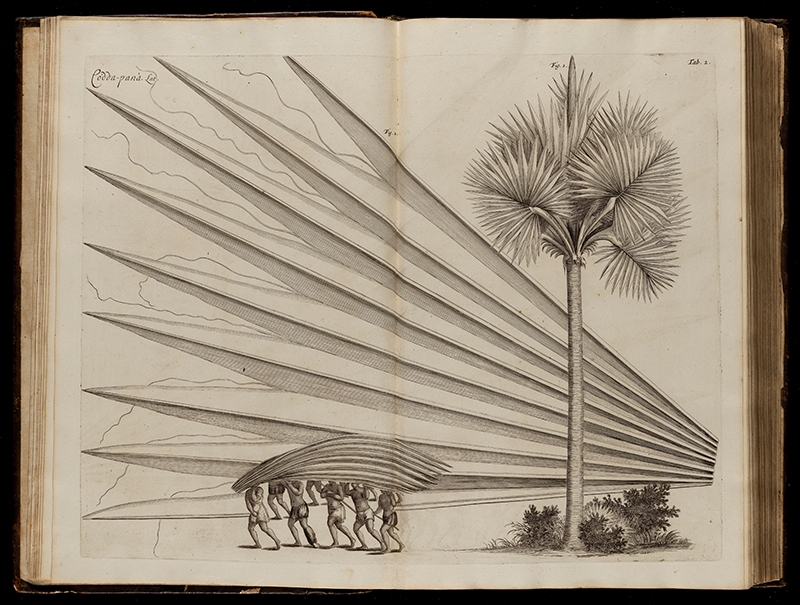

The resulting 12-volume, exquisitely illustrated ‘Hortus Malabaricus’ was a botanical masterpiece. It included wide-ranging information on the medicinal uses of 740 plants, most accompanied by double folio copperplate engravings.

It was also a deeply collaborative, multilingual project. The advisory team of physicians, scholars, botanists and artists helped with collecting specimens, identifying the plants by their vernacular names (written in Sanskrit, Malayalam and Arabic) and providing botanical data, geographical distribution and local uses, all based on their own knowledge and on materia medica manuscripts.

In this Van Rheede relied extensively on Ayurvedic physicians. Three Konkani Brahmin scholars – Ranga Bhatt, Apu Bhatt and Vinayak Pandit – provided textual and scholarly references. And healers from the Ezhava or low-caste toddy tappers community, collected plants and provided empirical functional taxonomies – on how these plants were used rather than their structure.

An illustration from ‘Hortus Indicus Malabaricus’, 1678–1693. By Hendrik van Rheede.

The main Ezhava informant for ‘Hortus Malabaricus’ was the well-known healer, Itty Achudan, who was considered so influential that an entire plant genus was named after him, Achudemia. Ezhava botanical classifications and medicinal garden schemes were recreated intact in Leiden’s botanical garden, Hortus Botanicus.

The text was enormously influential in the 17th-century botanical world. Ray Desmond describes it as “the main source for Carl Linnaeus’s knowledge of Asian tropical flora, yielding over 200 new genera and species for his Species Plantarum (1753),” and it was also referenced in works by Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910) and Sir Joseph Hooker (1817–1911).

Desmond quotes Linnaeus from the ‘Genera Plantarum’ (1754): “I have not put my whole trust in any author, excepting the very celebrated Dillenius and the work Hortus Malabaricus by the illustrious Van Rheede, having very firm convictions in their accurate data.”

If not for ‘Hortus Malabaricus’, India’s materia medica – and specifically, Ayurvedic and Ezhava ethnobotanical knowledge – would not have lived on in global science and modern botany.

Title page of ‘A Catalogue of Indian Medicinal Plants and Drugs’ by John Fleming, 1810.

Medicines from the bazaar

In 1810, John Fleming, an East India Company surgeon-botanist, published ‘A Catalogue of Indian Medicines’, which collected and listed indigenous medicines found in the bazaars or markets of India.

Fleming’s ‘Catalogue’ was among the first to draw attention to ‘bazaar medicines’ as well as those substances that could be considered poisonous (for example, Datura). His original intent had been to provide physicians newly arrived in India with the Sanskrit and Hindustani names of drugs, including their properties.

Fleming’s text was important as a precursor for the spate of catalogues of Indian medicine that followed, advocating the use of bazaar medicines as substitutes for British drugs or as potential cures for diseases not yet fully understood.

Chief among these catalogues was Whitelaw Ainslee’s ‘Materia Medica of the Hindoostan’ (1813). The six massive volumes offered botanical and English names for products, but also local names in Tamil, Telugu, Sanskrit and Dakhni for those that could not be identified botanically.

Other catalogues quickly followed. But this identification and classification of Indian materia medica created a framework of standardised pharmacological knowledge that wrenched botanical plants from their cultural contexts to insert them into chemical formularies.

Chaulmoogra oil factory of Prasana Kumar Sen, Chittagong (now in Bangladesh), 1921.

There are of course some examples of ‘inclusion’ of local materia medica into official pharmacopeia. One of the best known is chaulmoogra – seed and oils – that was used by hakeems and vaidyas as a cure for leprosy and incorporated within the British pharmacopeia, after which the German company Bayer obtained a patent for an extract of the oil.

But there have been far more examples of their exclusions and marginalisations. The plant Vishalyakarani disappears from the record – and bazaars – once the attempt is made to isolate its active ingredients. Similarly, Swietenia febrifuga vanishes as a cheap viable alternative to cinchona once the principle, cinchonine, was isolated from the original cinchona bark.

Heritage wars

A century later, these conflicts over Indian materia medica remain in post-colonial India.

Perhaps a final illustration will suffice, circling back to Fleming’s gorgeous 1813 engraving of turmeric (Curcuma longa) as displayed in the ‘Ayurvedic Man’ exhibition. This plate was chosen for display by the curatorial team precisely because of turmeric’s key role in the Indian medical heritage wars.

Turmeric (Curcuma longa): rhizome with flowering stem and separate leaf and floral segments. Coloured engraving after F. von Scheidl, 1776.

In 1997 the Indian government fought and won a costly legal battle to revoke a US patent for the medicinal use of turmeric to heal wounds, a therapeutic property well known in India for generations. The legal defense relied heavily on references to turmeric and its medicinal properties in Ayurvedic texts.

Largely to prevent future patent appropriations of medicinal heritage, the state launched the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL), perhaps the largest traditional medical knowledge compilation in the world. And what was once oral and intangible became an exhaustive database of codified medico-botanical knowledge, which ironically opens Indian medical heritage to new problems of exclusion, marginalisations and claims of ownership. The colonial cycle continues in a post-colonial age.

About the contributors

Sita Reddy

Dr Sita Reddy held a Wellcome Research Bursary in 2017 and is currently an independent scholar based in Hyderabad, India. She has guest-edited a special issue of Marg magazine on Indian botanical art, and is writing a book titled Medicine and the Jangala Books, both of which draw on her Wellcome research.