What can the experiences of astronauts tell us about our connection to home? Gail Tolley focuses on a Mars simulation in Hawaii to see what space travel reveals about homesickness.

Homesick for planet Earth

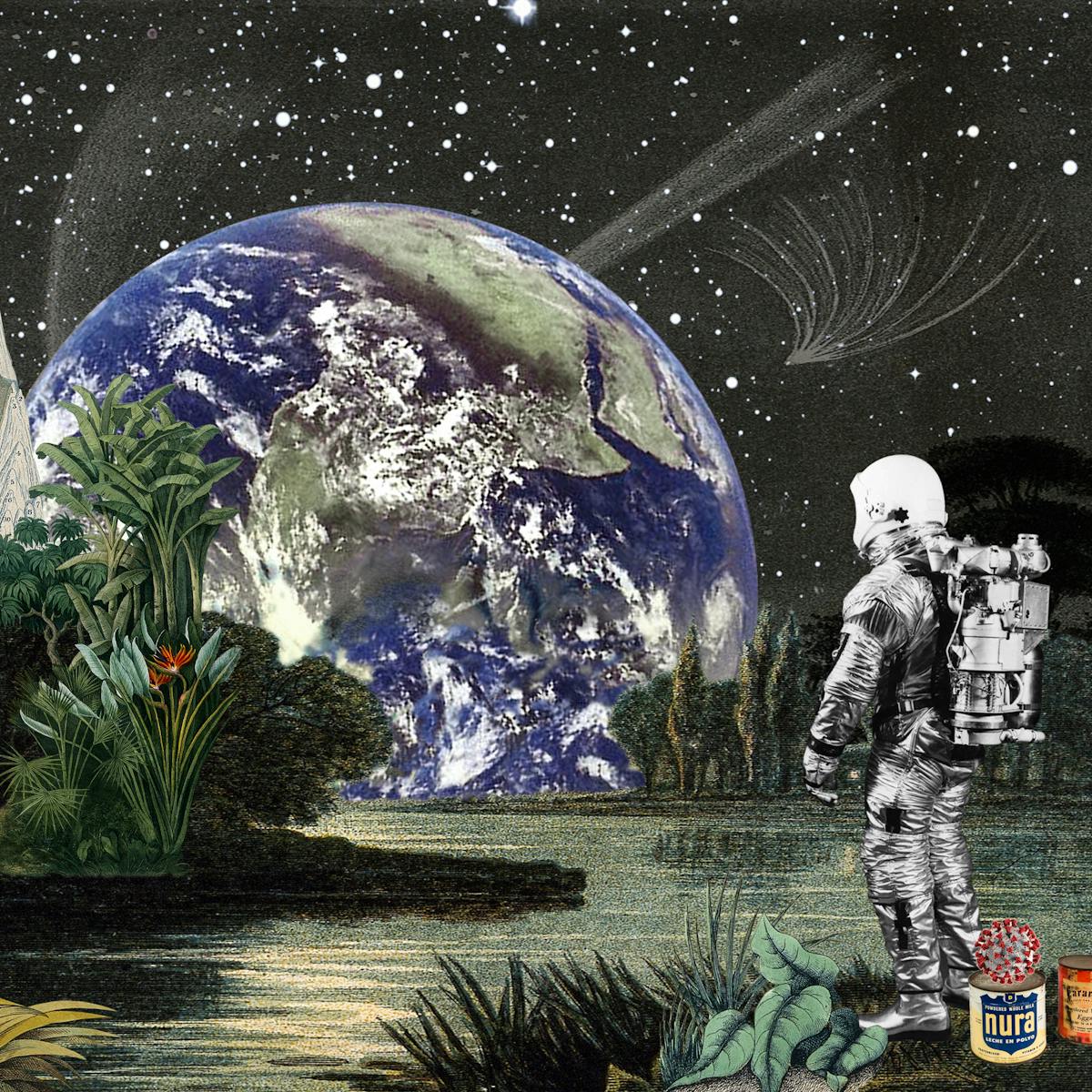

Words by Gail Tolleyartwork by Maria Rivansaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

What do you think astronauts in space do during their time off? Perhaps they do somersaults in zero gravity, tuck into some freeze-dried ice cream or read Douglas Adams. The actual answer might surprise you.

“Astronauts spend a lot of their time looking out the window at Earth,” Dr Peter Suedfeld tells me. “That’s the single most frequent way of spending their free time.” Suedfeld is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Psychology at the University of British Columbia. He’s spent his academic career studying how people respond to living in extreme and isolated environments, from scientists in Antarctica to those who’ve gone into space.

His anecdote fascinates me. The idea that astronauts, who have spent years training for their mission into space, find themselves captivated by the planet they’ve left behind once they get to a space station seems a little ironic. I wondered if those who’d travelled so far from home could teach us something about homesickness.

Life on Mars

On the slopes of the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii is a large, white geodesic dome. There is a very specific reason it’s located here in this barren, other-worldly landscape: since 2013 it has housed participants of a Mars simulation project called HI-SEAS (Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation).

Crew members enter the facility for up to a year at a time and live as if they are on a Mars space station. They can only step outside the building in a full space suit. Meals are made exclusively from dried and tinned ingredients. And communication to ‘Earth’ has a 20-minute delay – the amount of time a signal takes for a connection between the two planets.

If the project rings bells, that’s because it has already captured the imagination of the general public – in 2018 it was the focus of a podcast called ‘The Habitat’.

“On the slopes of the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii is a large, white geodesic dome, where crew members spend up to a year at a time and live as if they are on a Mars space station.”

Kim Binsted is the principal investigator on HI-SEAS. She was also the chief scientist on a similar Mars simulation back in 2007, spending four months cut off from the world in the Canadian Arctic. In short, she knows an awful lot about how people survive in these strange environments.

She sums up the ideal crew member as someone having “thick skin, long fuse, optimistic outlook”. (Also, it occurs to me, very good criteria for selecting a potential flatmate.) More specifically, she identifies the need for participants to possess a “weird combination of extroversion and introversion”. They must be able to get along living in close confinement with others, but also be able to keep themselves entertained.

When asked why I want to be an astronaut, I say I want Earth to be my home. I want it to be a place that I leave and see from the outside and return to.

The years Binsted has spent overseeing the HI-SEAS missions have taught her some other things about surviving far away from home. Successful crews are those who actively work at team cohesion – they set it as a task on their to-do list rather than hoping it is a by-product of the experience. Food also plays a key role. Crew members often made dishes from their home country – a way of celebrating familiar ties but also of looking after each other.

Binsted tells me about the time during her own mission when one of her fellow crew members, who was from Quebec, was feeling homesick. To cheer him up, the rest of the team decided they would make him poutine, a dish featuring fries, cheese and gravy. “We didn’t have any cheese; we didn’t have any French fries,” she says. “In the end we used reconstituted potatoes and fried those and made cheese from powdered milk – it took us all day. But he really appreciated it.”

This way of finding comfort through food brought to mind the empty shelves of my local supermarket in the early days of lockdown. While I didn’t have trouble finding toilet roll at the nearest Co-op, there was a gaping hole where flour and yeast should have been. We might have been at home rather than in a space simulation, but the baking boom was a clear sign of a pandemic-gripped Britain attempting to find reassurance and sanctuary in unsettling times.

“We might have been at home rather than in a space simulation, but the baking boom was a clear sign of a pandemic-gripped Britain attempting to find reassurance and sanctuary in unsettling times.”

A shift in perspective

Kate Greene is a writer and former laser physicist who took part in HI-SEAS in 2013. She also sees parallels between her experience in the simulation to our recent situation of self-isolation and lockdown during the pandemic.

“I have to say that there’s a collective homesickness now for what we’re experiencing. Because I think everyone realises that the world is changing and it’s not going to be the same and we’re not going to get it back. A pre-emptive homesickness or a grief for what we’re losing.”

Surprisingly, homesickness was something Greene felt more profoundly once she left Hawaii. “Homesickness is such an interesting topic,” she says. “When does it happen? Does it only happen when you are away? Can it happen when you come back and realise the world has changed out from underneath you? I think that’s more what happened in the years after, when I realised there was a changed world for me.”

Both Greene and Binsted also shared another insight that gave me a greater understanding of their attachment to home. Binsted has previously applied for US and Canadian space programmes, and when asked why she wants to go into space, she gives the following explanation.

“When you’re a kid, your house is your home. You go off to school and then you come home to your house. And then when you go off to college – that’s the time you start talking about your ‘home town’. When you’re a kid it’s just ‘town’. So your home town becomes your home because that’s what you return to. And if you leave your country and travel abroad, you might refer to your home country, because, again, it’s the place you hope to return to one day.

“So when asked why I want to be an astronaut, I say I want Earth to be my home. I want it to be a place that I leave and see from the outside and return to. Because that’s the definition of home. It’s nice here: that’s why I want to go away.”

Greene adds: “It’s a particularly poignant thing to send emissaries from our species out beyond this planet to have this experience of understanding how much this place is home. That’s probably one of the most profound perspective shifts that can happen.”

“US astronaut Alfred Worden famously said, ‘Now I know why I’m here. Not for a closer look at the moon, but to look back at our home, the Earth.’”

This view of home – that it’s something that’s truly valued once you’ve left it – has been echoed by others. US astronaut Alfred Worden, part of the Apollo 15 mission, famously said, “Now I know why I'm here. Not for a closer look at the moon, but to look back at our home, the Earth.” If there’s one thing that astronauts and I share, it’s the idea that home and our connection to it is something to treasure.

The adaptable human

Advances in technology mean that in the future more and more people could experience space travel. Space tourism, a moon station, perhaps even travel to Mars are all possible. But I wonder how humans would fare so far away from home. How homesick would we get? Perhaps we would experience the pre-emptive homesickness Kate Greene mentioned – or maybe we would adapt quite easily.

“That’s the human speciality: we’re really good at adapting to our environments and rising to that challenge,” says Binsted.

Suedfeld agrees. “People tend to build things that remind themselves of what they’re used to or where they came from. Presumably a moon station or a Mars station won’t be that different from some of the Earth environments. In general we will try and make it comfortable for ourselves. I think people will adapt.”

However, Suedfeld does pose another – intriguing – question about humans colonising remote planets. And that concerns the idea of humans on Mars. “The one thing I think will be a problem, one thing that will be different that no one has experienced before, is being in a place from which you can’t see Earth,” he says.

From Mars, Earth is just a tiny pinprick of light that no one could differentiate from millions of other stars and planets. “Astronauts spend more of their free time looking out the window at Earth than anything else. Well, what happens if you look out the window and you can’t see it? What kind of psychological impact will that have on people? I really wonder.”

About the contributors

Gail Tolley

Gail Tolley is a travel and culture writer based in Edinburgh. She has twice been the editor of popular culture magazines: Time Out London (2017–19) and The List (2012–14). She has contributed to National Geographic Traveller, the Independent and BBC Radio 4. Alongside working as a freelance writer and broadcaster, she also works in TV development.

Maria Rivans

Maria Rivans is a contemporary British artist known for her Surrealism-meets-Pop-Art aesthetic. With its unique approach to collaging, her artwork intertwines fragments of vintage ephemera, often with reference to film and TV, to spin bizarre and dreamlike tales. She exhibits work throughout the UK as well as internationally, including Hong Kong, New York and across Europe. Notable solo shows include the Saatchi Gallery, London and Galerie Bhak, Seoul.