Illustrations show that blindness was not uncommon in the Middle Ages, and that sighted people helped those with low vision get around. But did blind people then use guide dogs too, just as we do today? PhD researcher Jude Seal delves into medieval manuscripts to unearth 600-year-old evidence.

Men with dog’s heads, jousting rabbits and penis-growing trees are just some of the weird and wonderful illustrations you can find in medieval manuscripts.

If we believe that they are an accurate representation of the world, then medieval Europe was a far more diverse, interesting and frankly strange place than today. We know that these images were not exact illustrations of the world, but what about images that seem much more possible?

After all, some images are illustrative. For instance, researchers use the term ‘historiated’ to describe illustrated initials – for example in illuminated manuscripts – that contain identifiable historical figures. But other letters are simply ‘inhabited’, containing an unidentified figure that might be real or imagined. The same goes for images outside of initials too: the figures they depict are part of what was going on inside the minds of medieval scribes and illuminators, a mixture of the real and the imagined.

I am a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London, and research the intersection of the histories of medicine and magic, and the archaeology of disease. One of the things my work explores is the treatment of and attitudes towards disease and disability in the Middle Ages. Disabled figures regularly appear in medieval European images. This might reflect a more accepting attitude toward disability than we see in today’s media, which rarely features disabled individuals, except when their disability is the focal point of an emotional story.

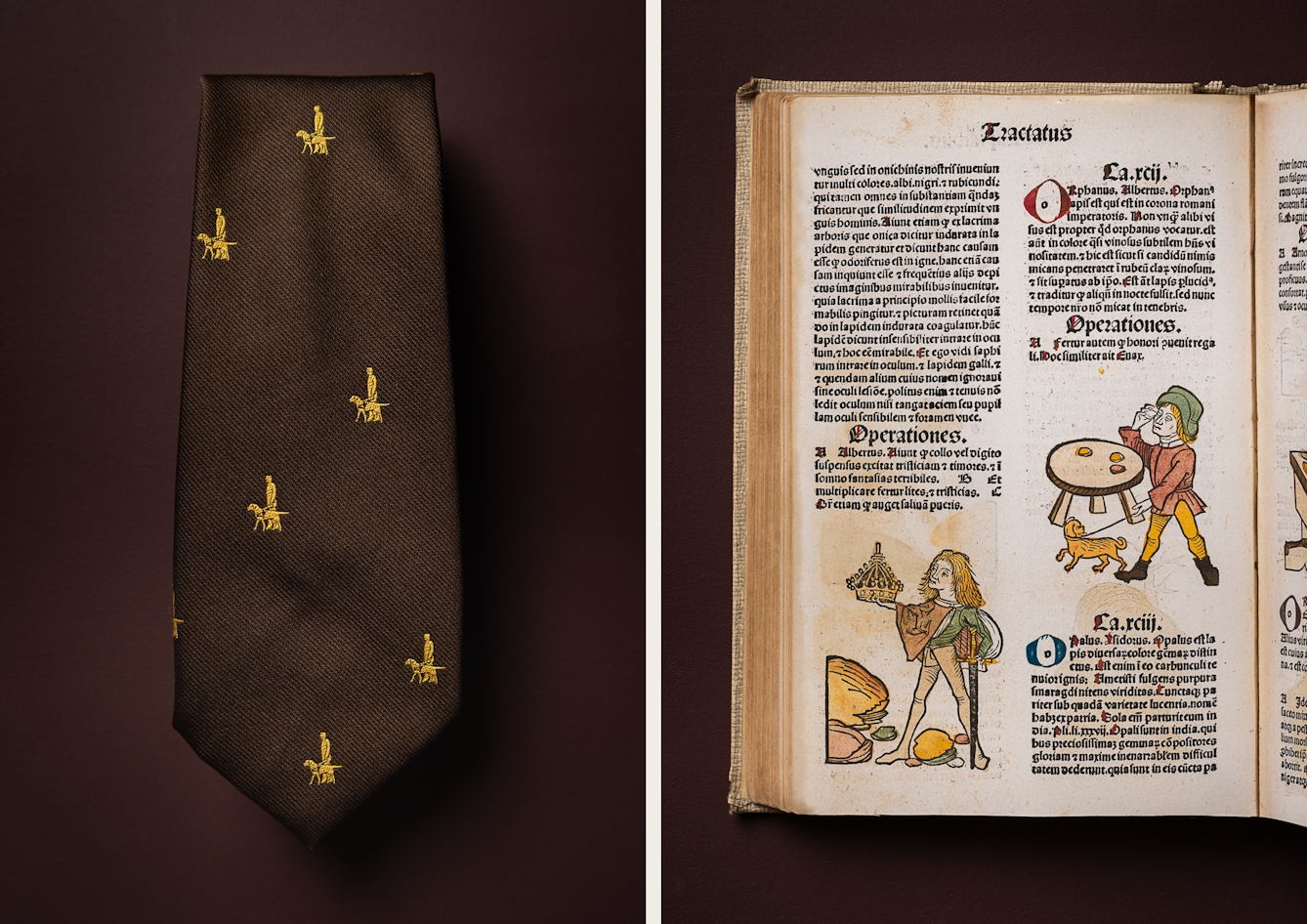

Guide Dogs for the Blind Association tie with the ‘Ortus sanitatis’, 1491.

But sometimes it’s not clear what is happening in an image that’s hundreds of years old, or whether the person depicted is disabled, and when I give talks or chat with interested colleagues in other disciplines, I'm often asked about what is going on in these pictures. What do they mean?

In 2018, historian Krista Murchison published a blogpost titled ‘Guide Dogs in Medieval Art and Writing’, which she begins by asking: “Were there guide dogs in medieval Europe? And what is the earliest picture of a guide dog? These questions are important for the history of disability and for our understanding of medieval culture.” Murchison’s post got me thinking about what we can see in early images and how those images fit with other evidence.

Decoding drawings of dogs

There were definitely blind people in medieval Europe. Without widespread eye care, and with a more ‘relaxed’ attitude to workplace health and safety, blindness was likely to be more common than today – historian Edward Wheatley writes that “varying degrees of visual impairment must have been so widespread as to be unremarkable, especially before the Italian invention of eyeglasses…” You could go blind as a result of an illness, and blinding was also used as a punishment.

Both work-related incidents and blinding as punishment would apply more to common people than the nobility, though there were some notable examples of blind aristocrats, such as King John of Bohemia, who lost his sight due to eye disease in the 14th century. Either way, it is undoubtedly true that in the West there were, in all probability, more blind people than today. It is also worth noting that blindness did not force individuals to resort to begging as their only source of income.

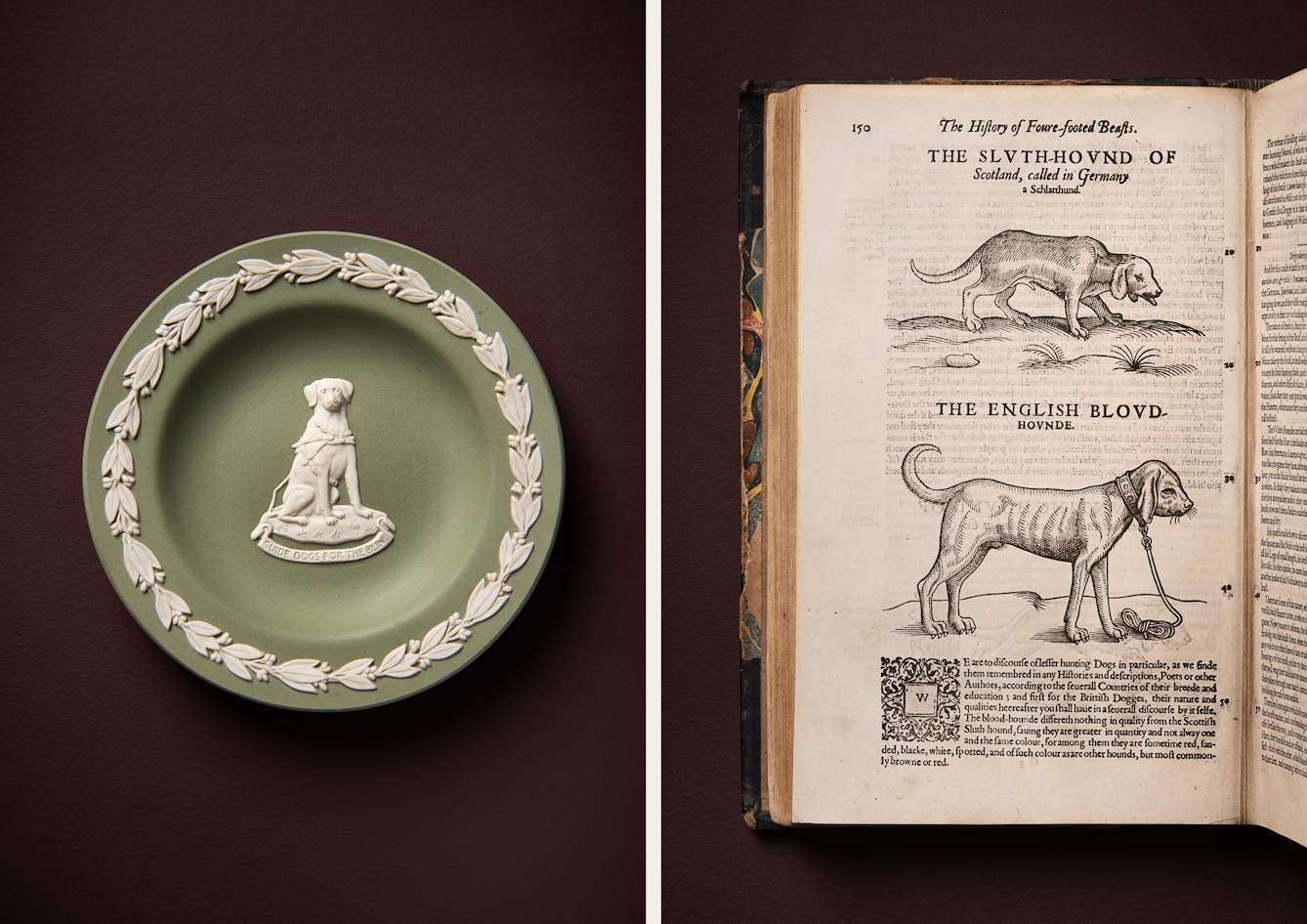

Guide Dogs for the Blind Association Wedgwood Jasperware plate with ‘The History of Foure-Footed Beastes’, 1607.

But what about guide dogs? We must begin with a fundamental question: “What makes a dog a guide dog?” After all, even today guide dogs are physically indistinguishable from any other of their breed – it is their training (and its associated, colour-coded jacket) that distinguishes them. So how do we identify a guide dog in a medieval image?

We could assume that a medieval guide dog is any dog that is positioned in front of (in the direction of travel) and on a lead held by a person believed to be blind. In medieval art, for the most part, there are two common representations of blindness – people with closed eyes, and people who are blindfolded. By this logic, all it takes to be a guide dog is to be held by a person who is presumed to be blind.

But is the dog guiding someone, or is it just in front of them? Many a dog walker will testify that their dog is often just a little bit more excited for walkies than the human on the other end of the lead, and strains ahead.

Similarly, is the individual blind, or have they just closed their eyes? Or does the scribe find eyes difficult to draw? One of Murchison’s examples of a “guide dog with a bowl” features a group of three musicians playing various instruments. The dog is held by the one who appears to be playing a hurdy-gurdy. Is he blind? He doesn’t have any eyes. But it might not be that simple, since he is missing a nose and mouth too!

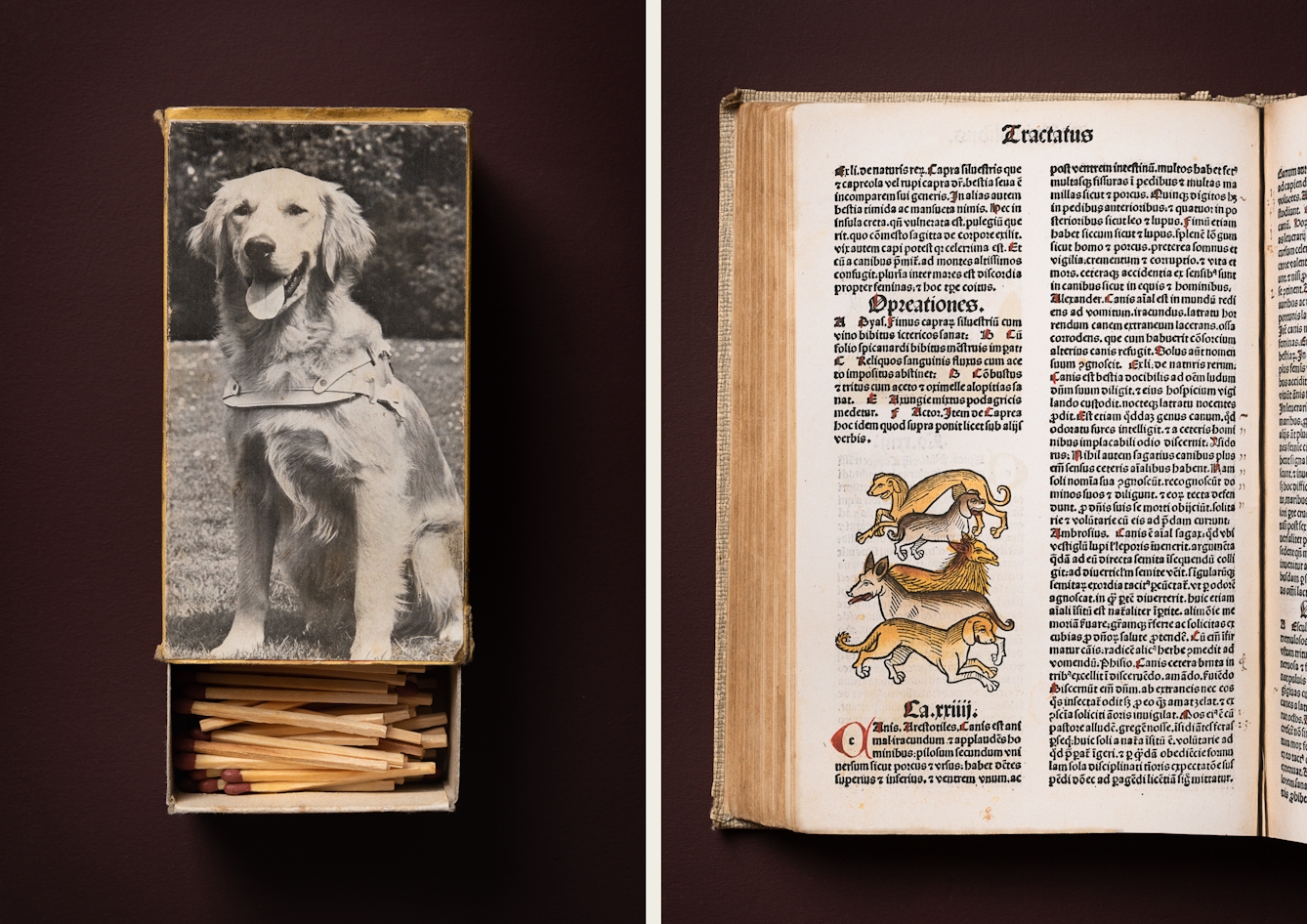

Guide Dogs for the Blind Association matchbox with the ‘Ortus sanitatis’, 1491.

Human guides and distracted dogs

Medieval people definitely used guides. Historian Edward Wheatley has compiled a wide variety of medieval written sources that refer to blind people being guided by others. In most cases the guides are young boys, poor adults or, in a couple of cases, other disabled individuals. Irina Metzler has found some written references to dogs as guides, but the term ‘guide’ usually relates to human guides rather than to dogs. The earliest reference – from Bartholomaeus Anglicus’s ‘De proprietatibus rerum’ (c. 1240) – actually states that dogs are too easily distracted to be guides.

Did medieval people use guide dogs? Quite possibly. Do we know for sure? Not yet. Medieval marginalia document all sorts of things, both from the real world and the imagination.

So what would it take to prove that a dog was a guide dog? The “nearly gold standard” would be if we found that a historical figure had used a dog as a guide and multiple people wrote about it back around the time the person lived. Without that, the next best thing would be if images of dogs leading people were clearly illustrative of a specific person referred to in the text. Even better if this was then repeated elsewhere too.

Without this, I strongly suspect that most illustrations are simply very good dogs.

About the contributors

Jude Seal

Jude Seal is a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London, researching the cultural perceptions of blindness, deafness and mutism in English miracle literature between 1070 and 1450. Their research explores the intersection of the histories of medicine and magic, and the archaeology of disease. They also write on living with a brain injury and chronic pain, and in their spare time are involved in disability sport.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.