Since 2004, photographer Julian Germain has been creating group portraits of multi-generational families, exploring the effects of time and questions of nature versus nurture. But in 2020 the Covid-19 pandemic forced a hiatus on the project. These recent portraits, and the stories accompanying them, celebrate families’ ability to come together again.

I have been looking out for four- and five-generation families, in order to make their group portraits, since 2004. There is something compelling about using photography to chart the effects of time, the ageing process and the cycle of life across the faces of multiple generations from the same family. Individually, we are all unique in the characteristics we possess, yet we are tied together by a common thread of genes.

The idea to make ‘Generations Portraits’ came from a desire to delve deeper into these themes and existential questions. I sensed that by photographing just one person from each generation in their family home, in a straightforward, honest way, a rich series of conversations could be initiated.

I use a large-format camera, which meticulously records the domestic scene as well as each sitter’s appearance in fine detail. My aim is to draw viewers in, to encourage them to explore shared features and differences and, perhaps, to consider the incredible role of genetics across many more generations than appear in the picture.

Fascinating questions arise about nature versus nurture (such as mothers and daughters wearing similar clothes), or the various phases of life, from infancy to very old age, and the experiences of each person depicted, living through very different social and historical times.

Since 2004, families have continued to come forward for ‘Generations Portraits’, albeit slowly and generally via word of mouth. But the lockdowns and restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic forced families apart. My portraits often need three separate households to come together under one roof, something that was just not safe and at times was even illegal.

The stress and strain this forced separation placed on families is easy to underestimate. Major life events like births and deaths reduced to being shared, celebrated and grieved over the flat screens of our digital devices.

The easing and end of restrictions in July 2021 meant that families could begin to reconnect in person. These portraits and words reflect on how each family reacted and adapted to the challenges they have faced, as well as what their family and their heritage mean to them.

Edith Stannard’s family

Edith Stannard, 103, Gwen Ladd, 80, Theresa Mayhew, 58, Sarah Brown, 32, Rayn Rose Brown, three months. 2021.

Edith Stannard’s first husband, Percy Stammers, was one of the 13,000 Allied prisoners of war who died building the Burma railway during World War II. Their daughter Gwen was born in 1941 and for many years she felt that her earliest and faintest memories involved her father. But more recently she has come to realise that she was too young for those recollections to be real and that they actually stem from just a couple of photographs, taken while Percy was home on leave in 1941.

Edith, now 103, Gwen, 80, and her daughter Theresa, 58, have all lived together in the same house for several years, alleviating two of the most debilitating social effects of Covid: the enforced separation of families and, in particular, the isolation of elderly people.

Left to right: Gwen and her father, Percy Stammers, 1941. Edith and Gwen, 1941. Gwen and Teresa, 1964. Sarah, 1990.

They still had to be very cautious, even within their ‘bubble’, because Teresa’s work as a school finance manager required her to go into the office on a regular basis. She and her daughter Sarah also faced the ordeal of separation and distance throughout Sarah’s pregnancy, which was not routine because Sarah and her partner had previously endured recurrent miscarriages.

“My pregnancy was actually all right, but for me, the whole way through, it was very stressful. I couldn’t help being worried all the time.” There were video chats, phone calls and texts, but the lack of real contact was painful for both of them – Sarah remembers seeing her mum in the flesh on just two or three occasions, standing outside on the drive, several metres apart.

Thankfully, Rayn arrived safely in May 2021, just as lockdown was starting to ease, and the day after they were discharged from hospital, she was driven straight to meet her gran, great-gran and great-great-gran, albeit through the living-room window. Having already been a great-grandmother for more than 30 years, Edith was delighted to finally make it to great-great-grandmotherhood.

Beryl Worsdale’s family

Isla Barrett-Worsdale, eight months, Adam Worsdale, 35, Alan Worsdale, 65, Beryl Worsdale, 87. 2021.

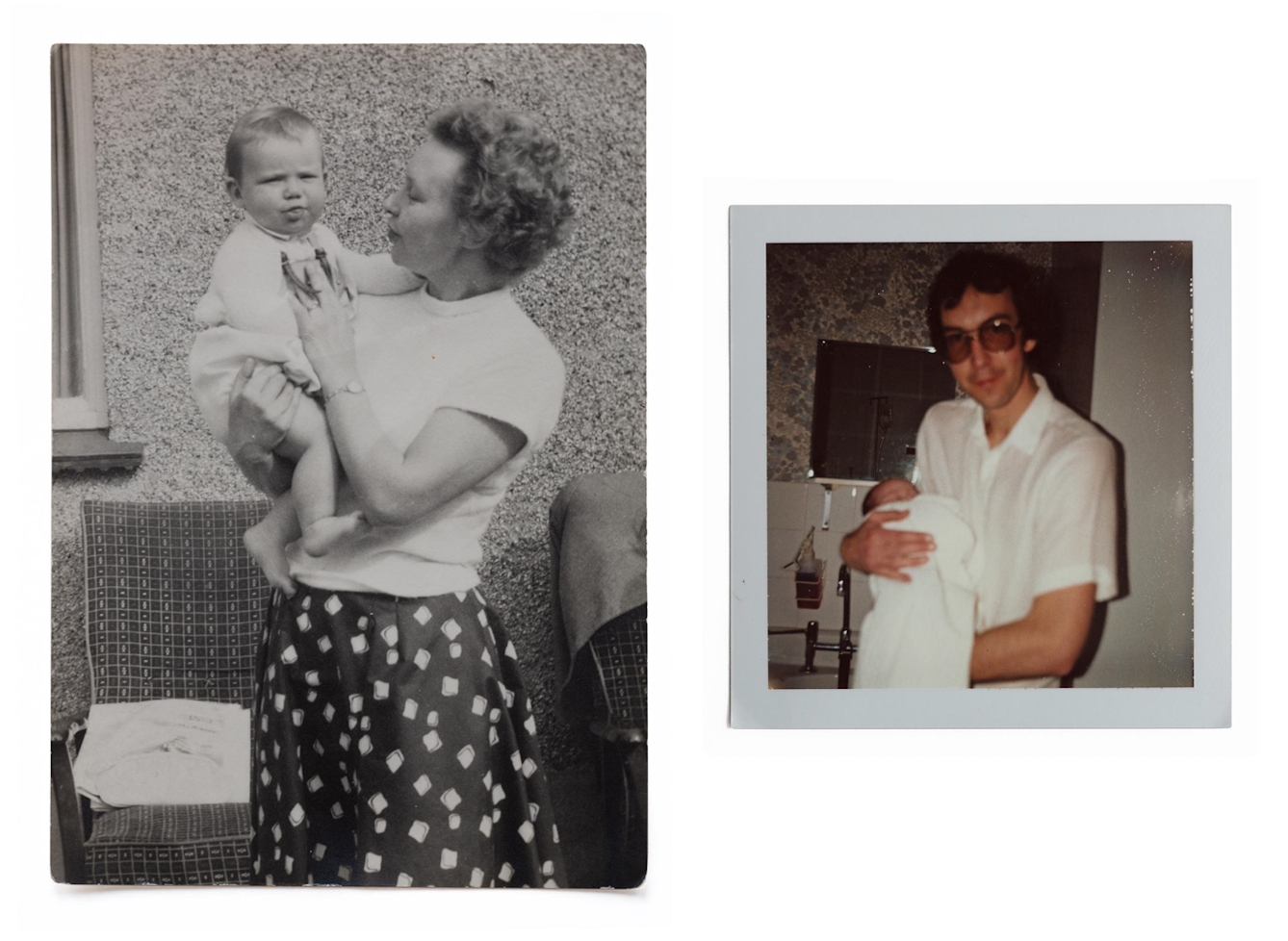

Alan and his 87-year-old mum, Beryl, both live alone but close by on the Essex coast. It made sense to bubble, while still being very careful to distance, because he was going out to do both their shopping. Adam and his wife Nicola lived in London, and her entire pregnancy coincided with various stages of lockdown. They bubbled with Adam’s twin sister Amy throughout, but didn’t see other members of the family at all except via Zoom or FaceTime.

Adam’s daughter Isla was due at the peak of the second wave in January 2021 and both he and Nicola were afraid he wouldn’t be allowed to be there for the birth. He knew of several fathers who were only allowed into the delivery room briefly, spending many anxious hours waiting for news while sitting outside in their cars. He was hugely relieved (and considers himself very lucky) that just before Nicola went into labour, the hospital relaxed its rules, and he was able to fully experience Isla being born.

Left: Alan and Beryl, 1956. Right: Adam and Alan, 1986.

The Worsdales feel they have always been a very close family, but even more so since Alan’s wife (Adam and Amy’s mum) Angela died three years ago. Isla’s arrival was bittersweet in the sense that Angela had always been so excited about the prospect of becoming a grandmother.

As soon as Nicola and Isla left hospital, Alan drove to London to see his first grandchild. The meeting was outside and at a distance, so he couldn’t hold her, but they went for a short walk with Isla in a pushchair. The physical and emotional thread that runs through the family (and specifically between Isla and her deceased grandmother) was explicitly and officially conveyed when Isla was given Angela as her middle name.

A month after Isla was born, Adam and Nicola left London and moved back to Essex.

Andrew Little’s family

Andrew Little, 94, Margaret Preston, 65, Rachel Preston, 34, Caoimhe Jones, four. 2021.

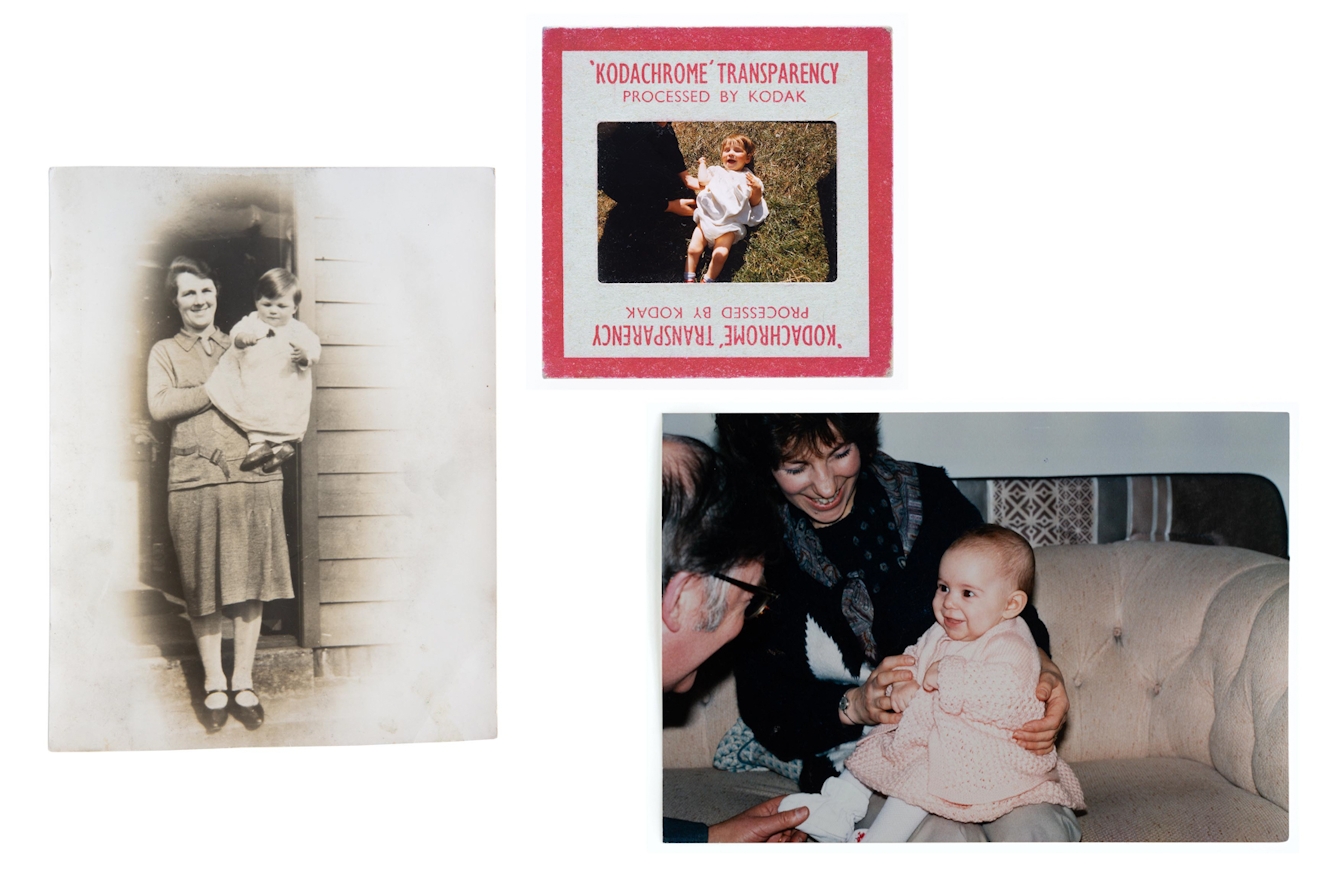

At the end of World War II. Andrew Little was conscripted and posted to Graz in Austria where, aged just 20, he met his future wife, Marianne. She was an educated Hungarian-Jewish girl of 19, whose father was murdered by Hungarian fascists and who had spent the entire war in hiding and in constant peril.

Just before the Soviets took control of Hungary in 1947, she escaped to Graz. Their daughter Margaret said, “Daddy was absolutely head over heels in love with her. His parents were horrified that he wanted to marry a foreigner, but they went on to have a passionate and loving marriage.”

Andrew, already a strong supporter of the Labour Party, became vicar of an impoverished parish in Stoke-on-Trent and Margaret, her elder sister and her two younger brothers spent most of their childhoods there. “We were brought up to believe in social justice and, to varying degrees, we’ve all inherited his leftish politics.”

Left: Andrew and his mother Grace, 1927. Middle: Margaret, 1957. Right: Andrew, Margaret and Rachel, 1987.

There might also be a link between the kind of ministry Andrew practised and the teaching profession. Marianne trained to be a teacher in her 30s, then Margaret became a teacher and married a teacher, and now Rachel and her partner are teachers too.

Andrew now lives in supported housing and until Covid, Margaret and her husband David could stay there in a guest room. “We visited every fortnight for two or three nights. In fact, we were there in March 2020 when lockdown started, and we literally had to pack up and get out. Then, of course, we couldn’t see him until July.”

To Rachel and her siblings, Andrew has always been ‘Papa’. Marianne had died when they were small, and Margaret remembers him grieving terribly. “He started travelling down to London to stay with us every other weekend and I think the kids were a very healthy distraction for him. He came on our holidays as well, so he’s been a huge figure in all their lives. They’re all in touch with him and of course there’s now a busy WhatsApp group for ‘Papa news’.”

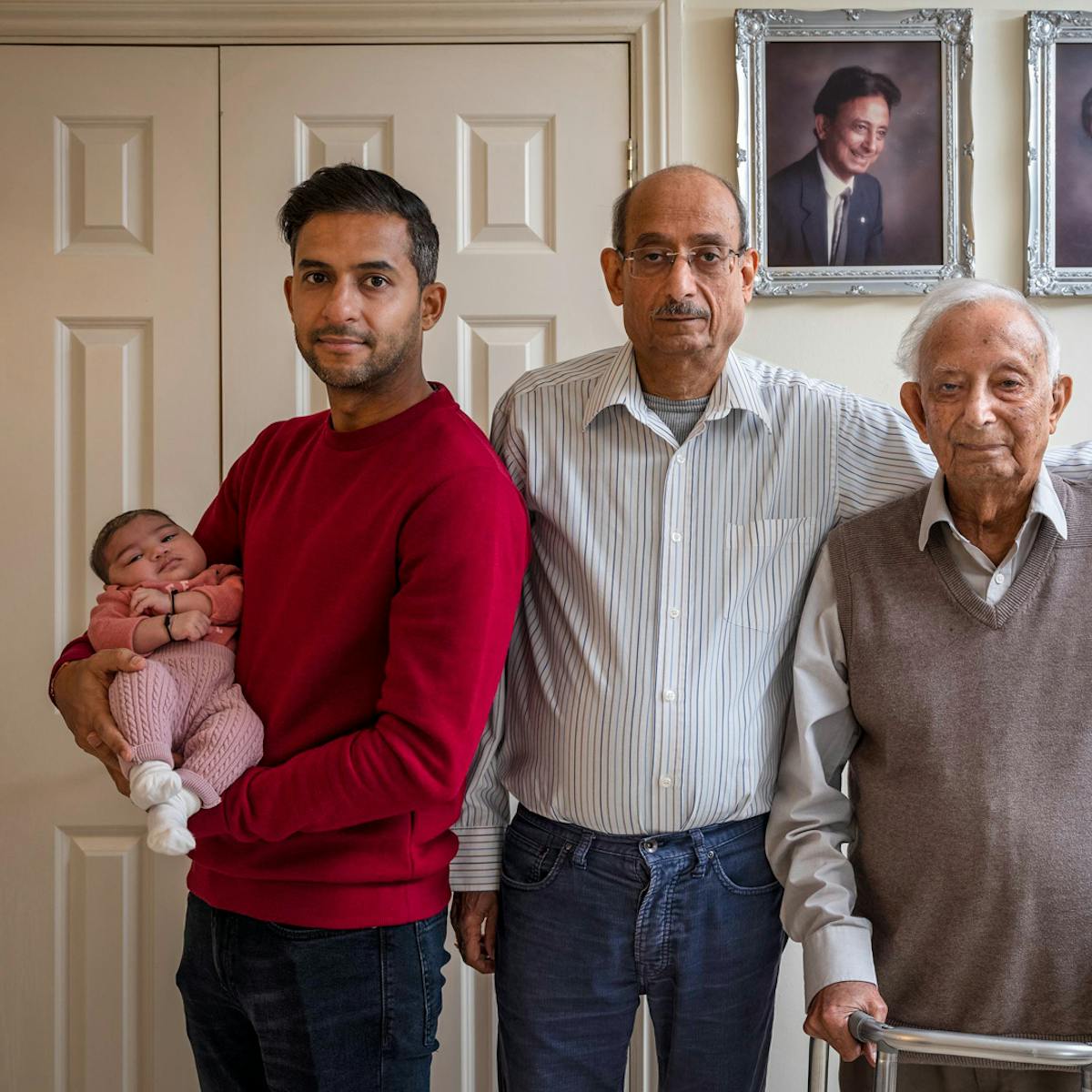

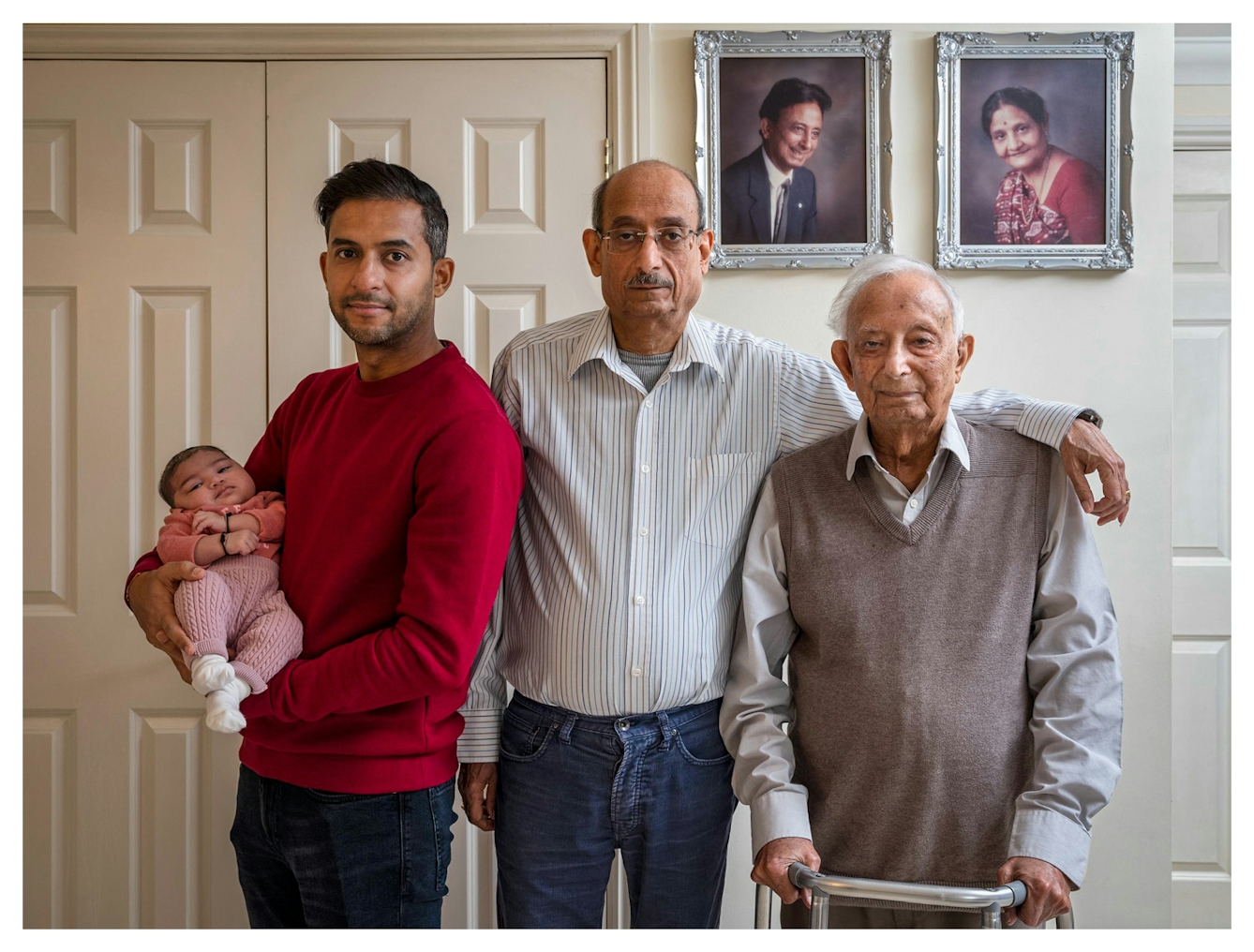

Bhagwanji Vasanji Popat’s family

Mahi Rani Popat, two months, Niral Vinod Popat, 36, Vinod Bhagwanji Popat, 66, Bhagwanji Vasanji Popat, 92. 2021.

Bhagwanji Popat and his wife Jaya have led extraordinary lives driven by ambition, necessity and, at times, oppression between Nyasaland (renamed Malawi after independence in the mid-1960s), India and the UK.

As a teenager, Bhagwanji trained to be a salesman (sleeping in the hardware shop where he worked) and taught himself English via the BBC World Service. He subsequently owned a stake in a variety of businesses in Nyasaland and ultimately became a partner in one of the largest conglomerates in the country, with a string of businesses in retail and manufacturing – everything from petrol stations to tea-blending to brick-making.

Independence for Malawi, however, led to restrictions being placed on the Asian population, such that in the early 1970s Bhagwanji felt he had to look for business opportunities further afield, opening a grocer’s shop in Hounslow in West London.

The family adapted to life between Malawi and the UK, but Bhagwanji’s two sons, Vinod and Hitesh, gradually built careers in England, and by the 2000s the whole family had followed. I met them all when they gathered together at Vinod and his wife Jyoti’s house in Leicester for the photoshoot – the three children (now all in their sixties), six grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren, as well as the in-laws.

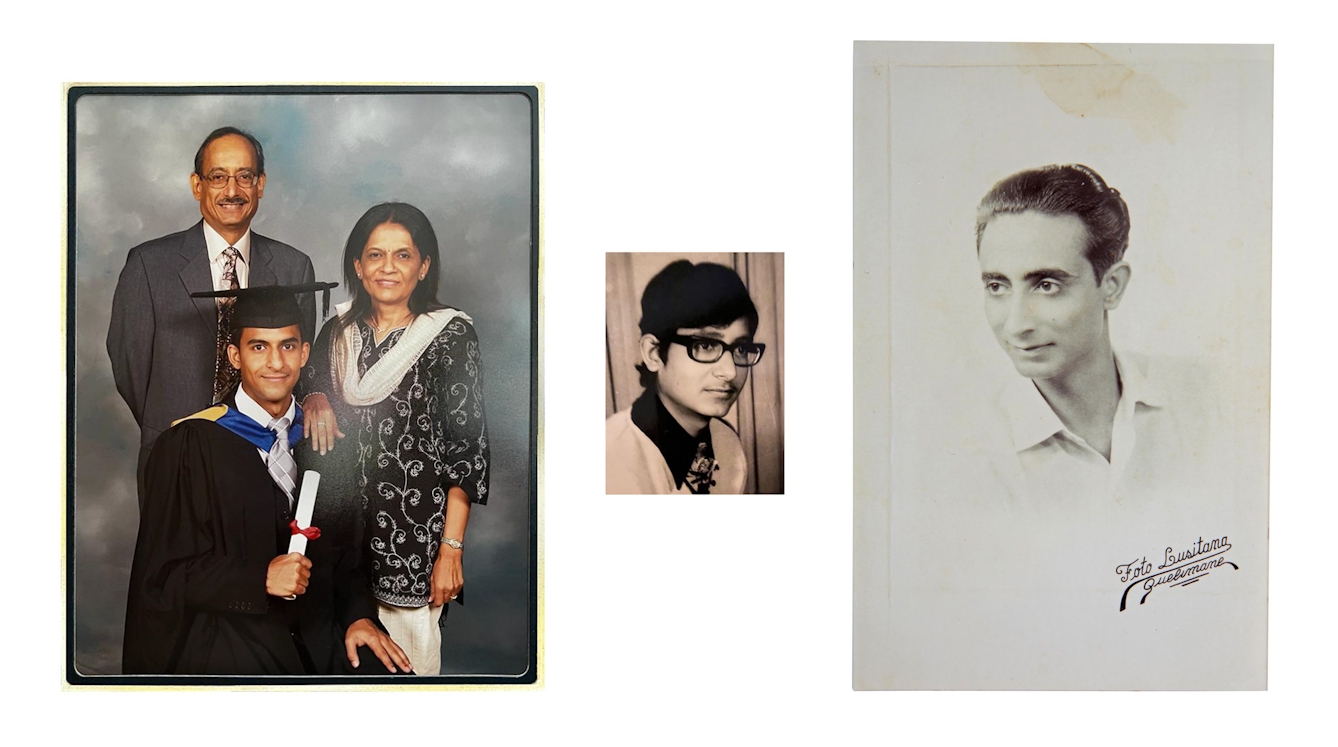

Left: Niral, Vinod, Jyoti, 2008. Middle: Vinod, 1970. Right: Bhagwanji, 1949.

I was struck by the impressive contribution and the range of skills that Bhagwanji and Jaya and their descendants have brought to this country: directors of media, finance and health companies, an HR consultant, a GP and a pharmacist, to name just a few of their achievements.

In Indian families, grandparents are often heavily involved in childcare and they, in turn, are cared for when they reach old age. The Popats are a prime example, with Bhagwanji and Jaya living with Vinod and Jyoti. Vinod’s son Niral and his wife Radhika and their two-month-old baby Mahi are here too, so there are four generations living under one roof.

I asked Niral, with his baby daughter Mahi in his arms, how he felt about the future, and he said, “One hundred percent optimistic! We are all really close. We look up to our elders, look after each other, we watch each other’s backs and we work hard. Sure, there will be challenges, but this family is used to facing ups and downs. I’m sure we will face them all and be OK.”

Elizabeth Ions’ family

Elizabeth Ions, 84, Linda Craig, 60, Lindsay Craig, 38, Poppy Gerber, three. 2021.

Betty Ions was one of six children born into a mining family in the North East of England. She married in her early 20s, and her husband was also a miner, and later a farm worker. When her three daughters and son were old enough, Betty worked as a cleaner and then, in the late 1960s, she found employment as an usherette at the Wallaw Cinema, a job she loved.

She talks fondly about hectic weekend matinees (‘shushing’ all the noisy kids) and the excitement of the packed houses for blockbusters like ‘Jaws’. Her favourite film star was Gregory Peck – “I’d watch anything with him in.”

Reflecting on the changes she’s seen over the years, Betty said, “The town isn’t as nice as it used to be. You could get everything you wanted, but nowadays there’s hardly any shops.”

Her daughter Linda agrees, “A lot of things have gone. There was a really good dancehall and there were several cinemas – not just the Wallaw, but also the Hippodrome, the Regal, the Pavilion or ‘Piv’, as we used to call it. That changed to a bingo hall, but that’s closed now too.” Today, the nearest cinema is 15 miles away.

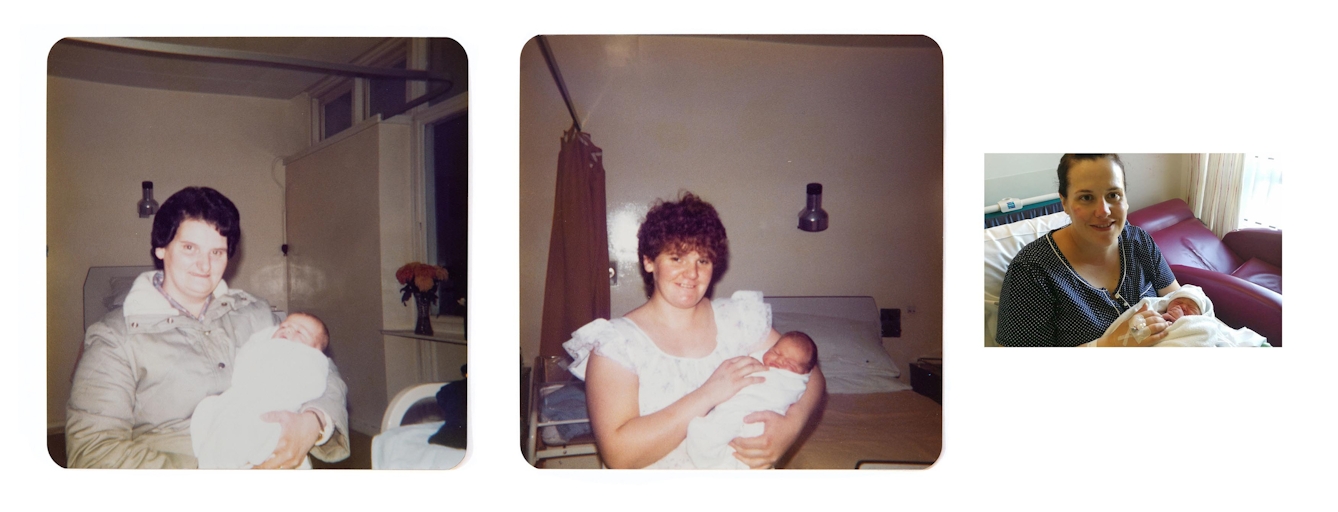

Left: Betty, Lindsay, 1983. Middle: Linda, Lindsay, 1983. Right: Lindsay, Poppy, 2018.

Many of the traditional clubs have gone too and they all offered live entertainment: singers, comedians, bands and magicians. “The town was thriving. There was lots of work, not just in mining, but also factories.” When Linda left school, she went straight into a job at the Hepworth’s clothing factory and all her friends got jobs too. She didn’t know anyone who went to college or university: “Maybe one or two got apprenticeships.”

Since the 1980s, the pits have all closed and many of the factories too. Work has become scarce in the area.

Lindsay and her friends stayed in education until they were 18 and then went to university. She studied in London but after graduation, for family reasons, she moved back to the North East. She has a job that she enjoys at the local mining museum and art gallery.

Linda and her husband Colin took on childcare for Poppy so that Lindsay could get back to work. They loved being with her almost every day and then suddenly, because of Covid, Lindsay and her partner Adam were furloughed. “We all had to isolate. It was very upsetting that we couldn’t see Poppy for months. It’s so hard to explain Covid to a two-year-old!”

Geraldine Cousins’ family

Gabriel Alberti, six, Josephine Rock, 31, Lucy Cousins, 57, Geraldine Cousins, 90. 2021.

Josephine Rock describes her family as “all being artists in some way”. Her grandmother Gerry is an illustrator who, at the age of 90, is working on her first collection of poems. Her mum, Lucy, creates children’s books (her dad, meanwhile, is a cabinetmaker), she herself is doing a master’s degree in Fine Art and, last summer, her six-year-old son Gabriel had a painting he made during lockdown included in the Royal Academy’s young artists’ exhibition.

Creativity has been encouraged and nurtured across the generations. “It’s like it’s just there, all around us, so it runs through our veins, really.” Lucy says that her most treasured possession is a painting of Josephine aged six weeks by her father, Derek Cousins. “It’s a link between my beloved daughter and beloved dad, so unique and beautiful. Particularly now that he’s no longer alive.”

Gerry has been writing a lot about her childhood. “As I’ve got old,” she said, “my memories of those years have got stronger. I think that’s normal, isn’t it? My brothers and my parents, my father’s experiences of World War I, added to the old photographs we have. It all comes back so vividly and it comes out in my poems.”

Clockwise from top left: Gerry and her brother David, 1941. Gerry, Lucy, 1966. Josephine, Gabriel, 2015. Lucy, Josephine, 1990. Josephine, age 6 weeks, 1990. Oil on canvas by Derek Cousins.

In a conversation about the future, Lucy expresses apprehension. “There’s a lot of things to worry about: inequality, politics, Ukraine, and environmentally things might just… collapse. I’m not feeling very positive about it, unfortunately. It’s hard to imagine what the world might be like in 50 years’ time, when Gabriel’s my age. I hope it will be all right, but I fear that it might not be.”

Gerry is more positive, citing humanity’s “extraordinary capacity for solving problems”. Lucy then wonders whether Gerry’s experience of living through the disaster of World War II might, paradoxically, have given her a more optimistic outlook.

“That was a time when you must have wondered how on earth it was going to end – and in the end, despite everything that happened, a lot of people got through it. Maybe that sets you up to believe that things can get better? I haven’t had that experience. I feel that my generation have, for the most part, had it really good.”

About the photographer

Julian Germain

Julian Germain’s photography is in essence ‘social’ and ‘humanistic’. His projects explore themes that affect people’s lives, including education, poverty, football culture or colonialism, or existential questions about what it is to be human, about life or death, or family heritage. He has exhibited internationally and published several books. A series of his Generations Portraits will be exhibited on billboards around Birmingham and the Black Country during this summer’s Commonwealth Games.