For Georgian Londoners, the allure of electric animals was both intellectual and sensual.

Eels and feels

Words by Ruth Gardeaverage reading time 4 minutes

- Serial

For Georgian Londoners, the allure of electric animals was both intellectual and sensual.

By the time James Munro wrote these words, scientific investigations into the electrical properties of torpedo fish and electric eels had been underway for over 200 years. His observations emphasise how their fascination, stretching back to antiquity, was still bound up with their mysterious and sinister potential to harm. The fearsome power of the torpedo inspired poetic disquisitions by Classical writers such as Claudian.

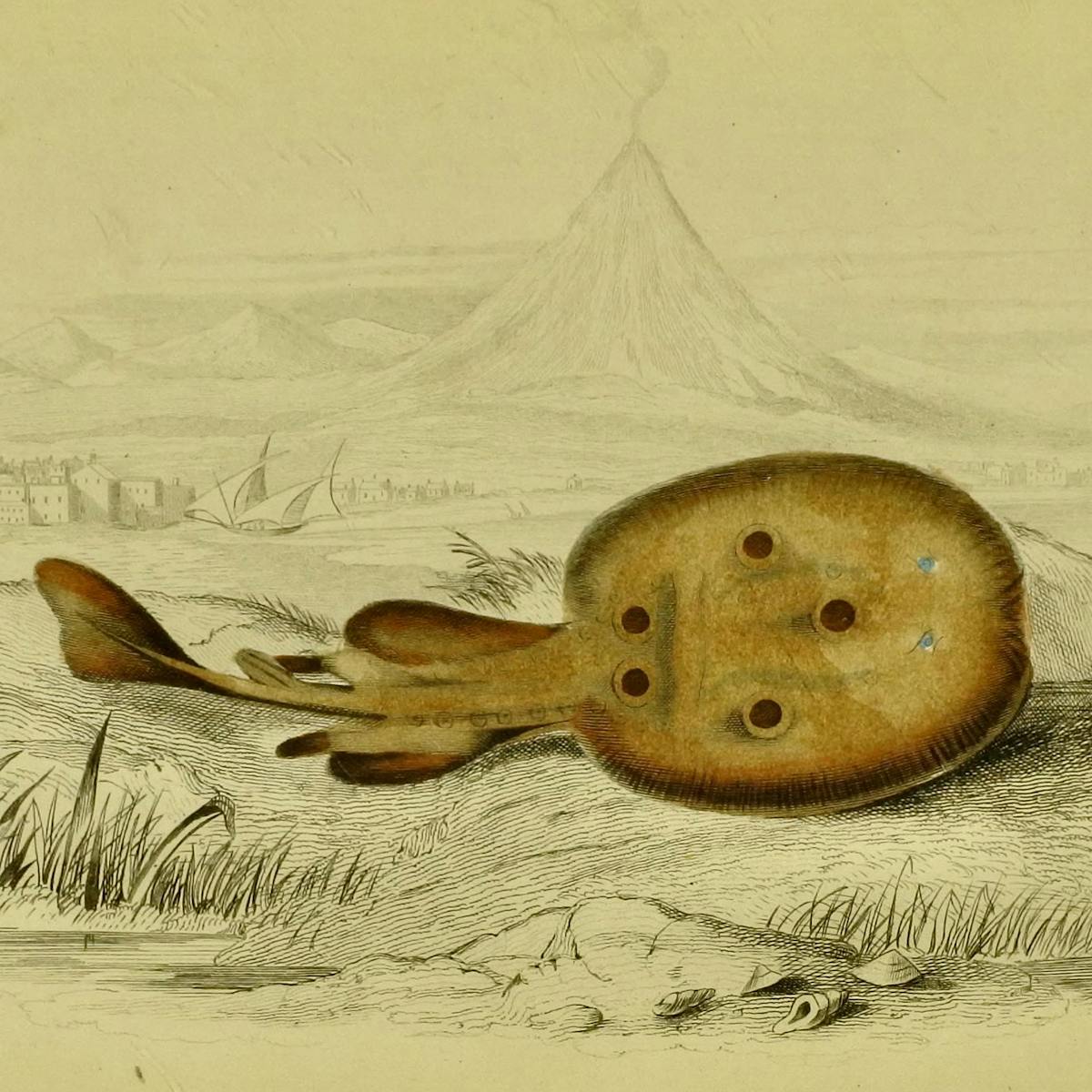

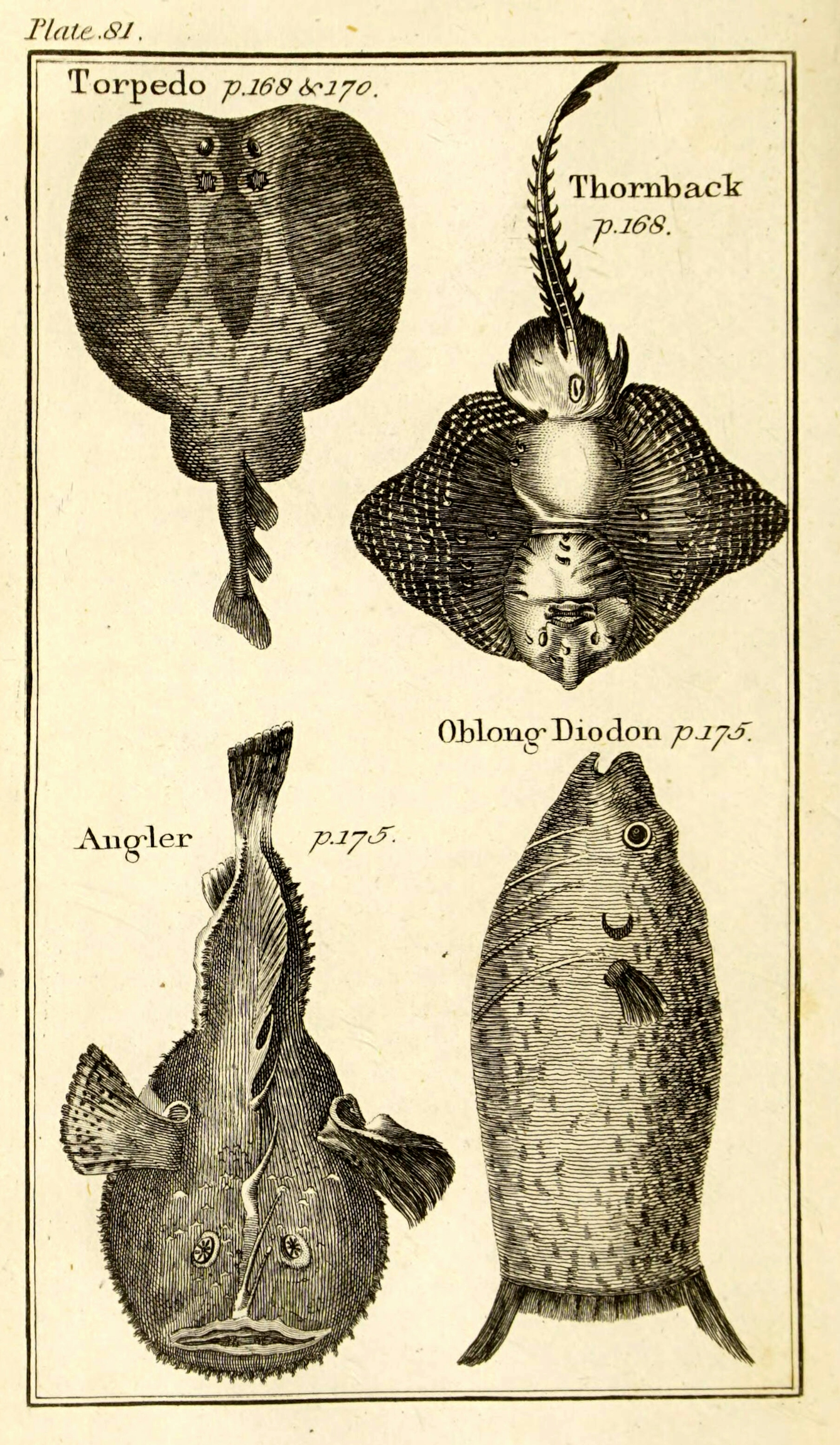

Guillaume Rondelet, a 16th-century naturalist, had observed the torpedo ray’s stupefying faculty in this study of marine life.

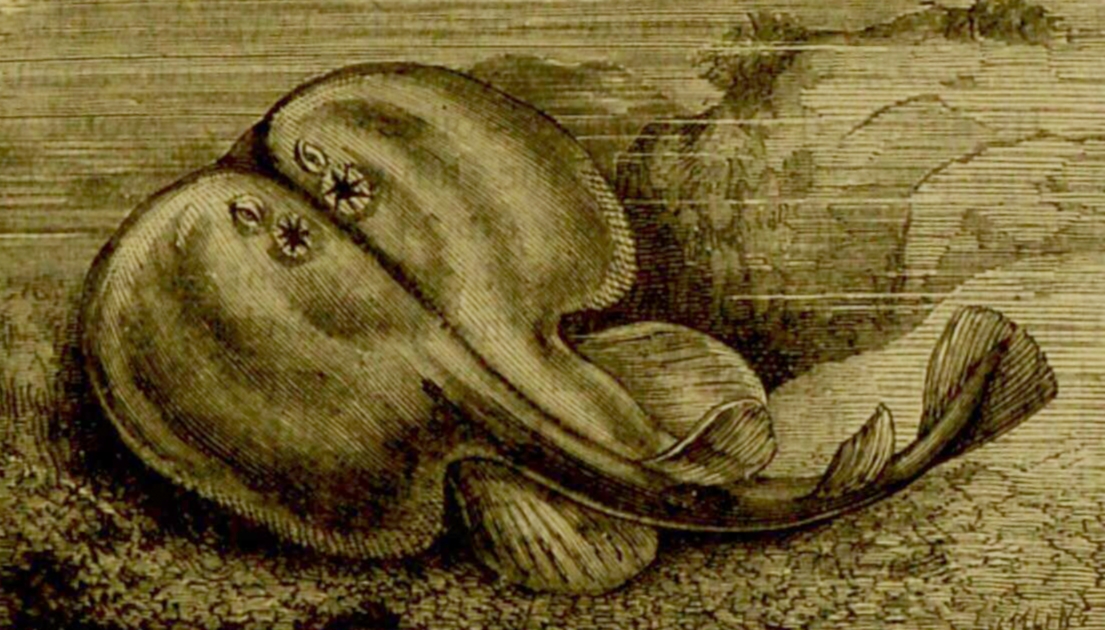

Until the 18th century, electric fish were still thought of in more or less fantastical terms. Seen as both wonderful and dreadful, these fish were thought to possess occult properties. Artemidorus Daldianus, a second-century Greek diviner, wrote that dreaming of a torpedo fish was a bad omen, indicating imminent danger and connivance. In medieval and Renaissance accounts, electric fish were to be found in bestiaries alongside such monstrous animals as dragons, griffins and basilisks. After Franklin’s discovery that lightning was another form of electricity, the interest in “torporific fish” was renewed, and they began to be scrutinised through a scientific lens.

In pictures

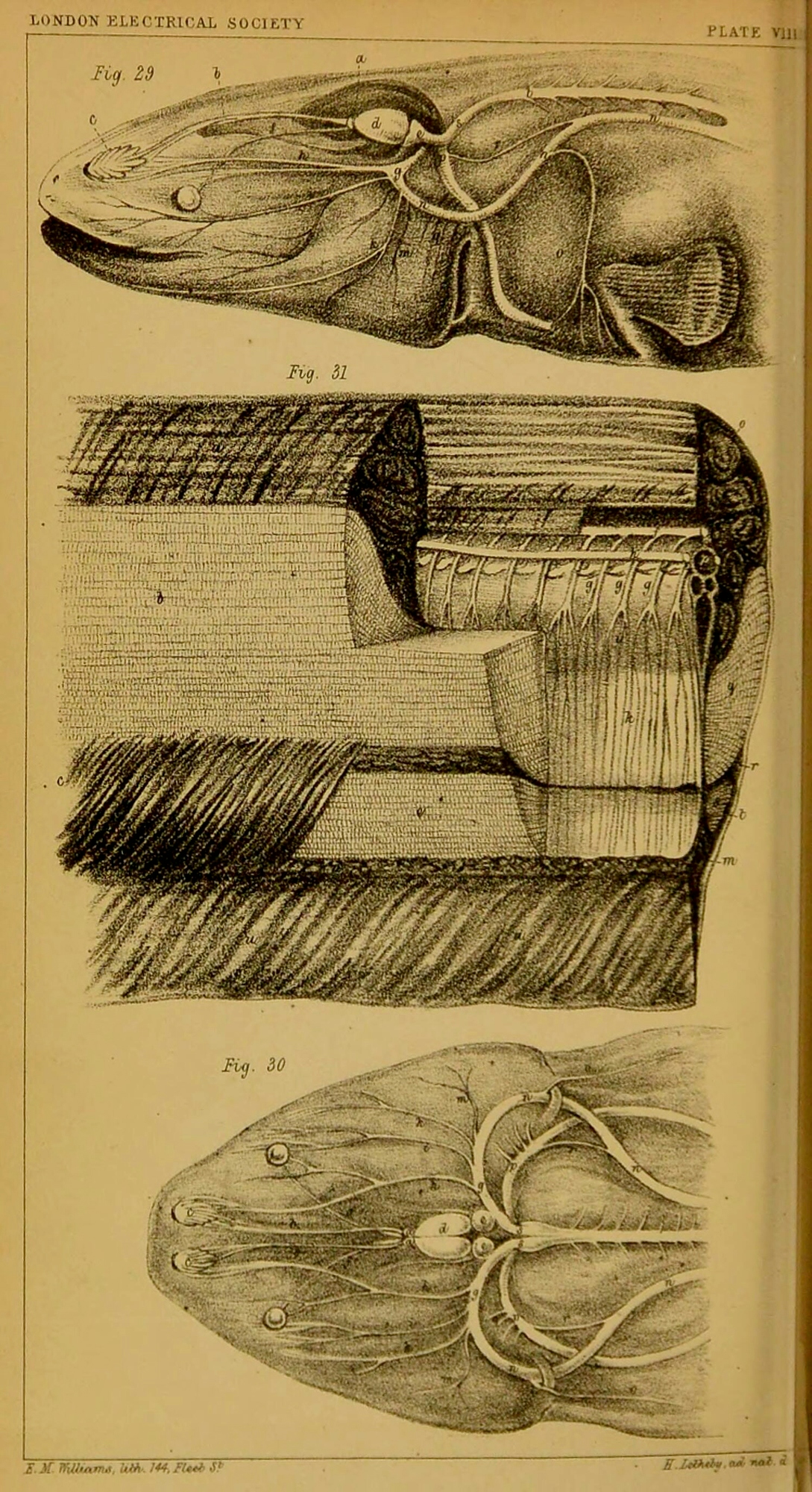

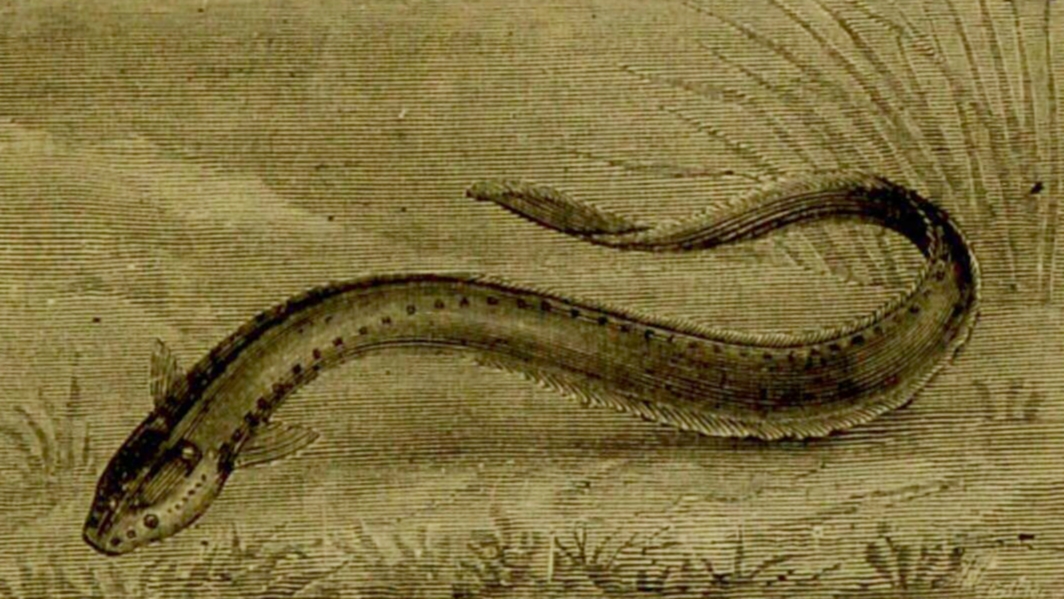

‘An account of the dissection of a Gymnotus electricus: together with reasons for believing that it derives its electricity from the brain and spinal cord, and that the nervous and electrical forces are identical’ by Henry Letheby. A chemist and medical officer of health in London, Letheby was interested in the medical application of electricity.

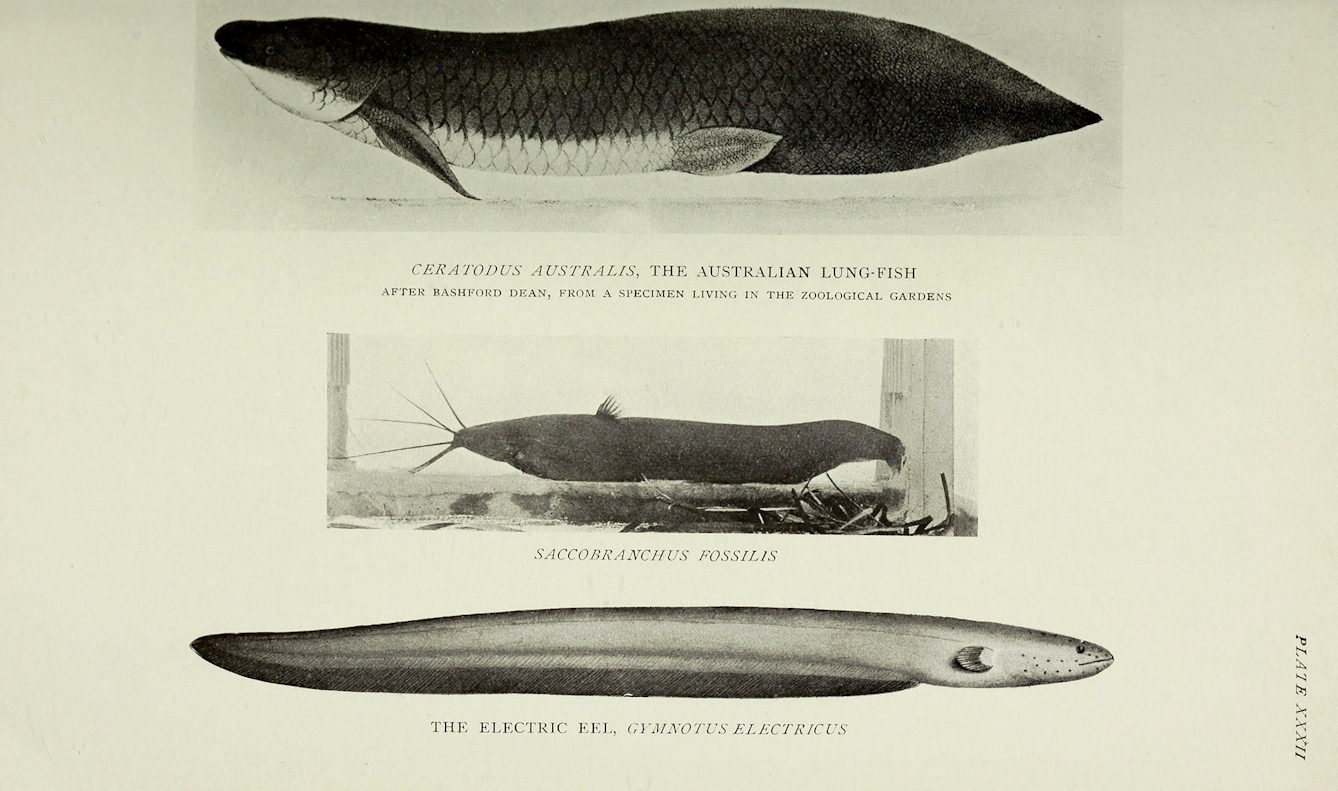

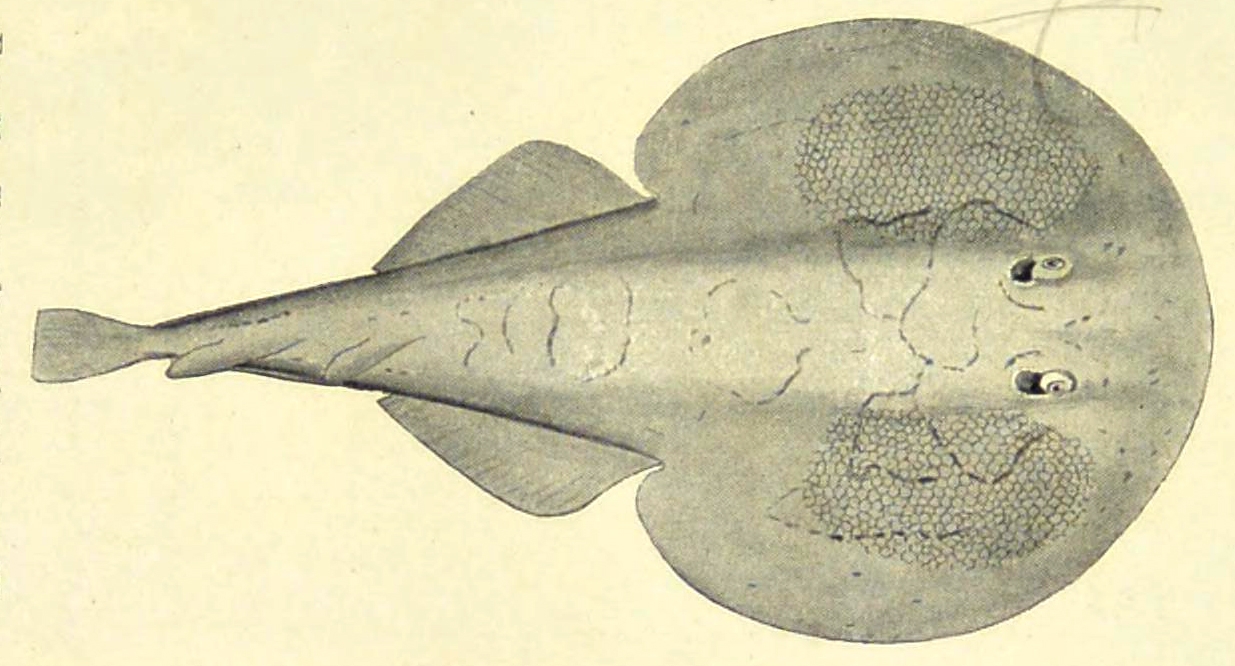

‘Reptiles, amphibia, fishes and lower chordata’ by Richard Lydekker.

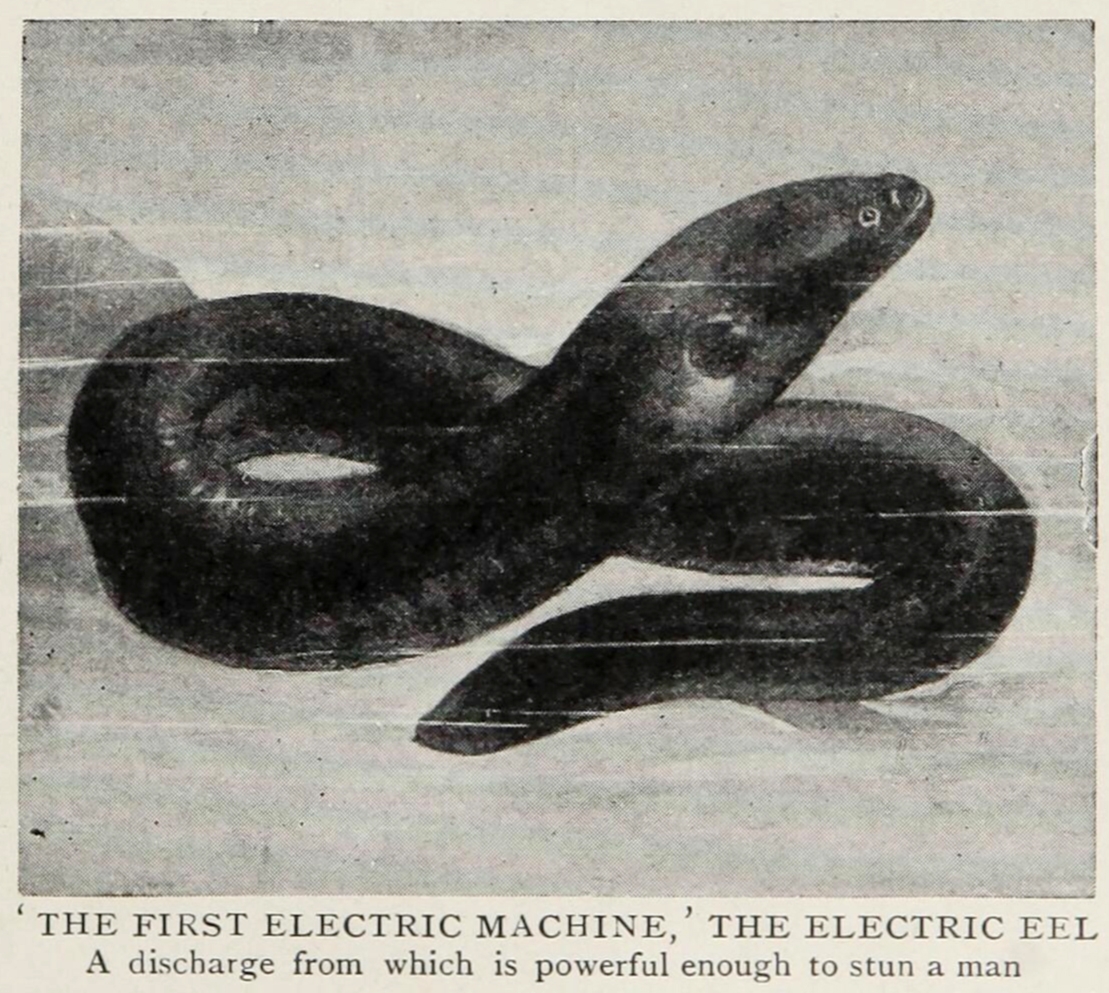

Arthur Mee’s Popular Science magazine described the electric eel as the “earliest electric machines used by man”.

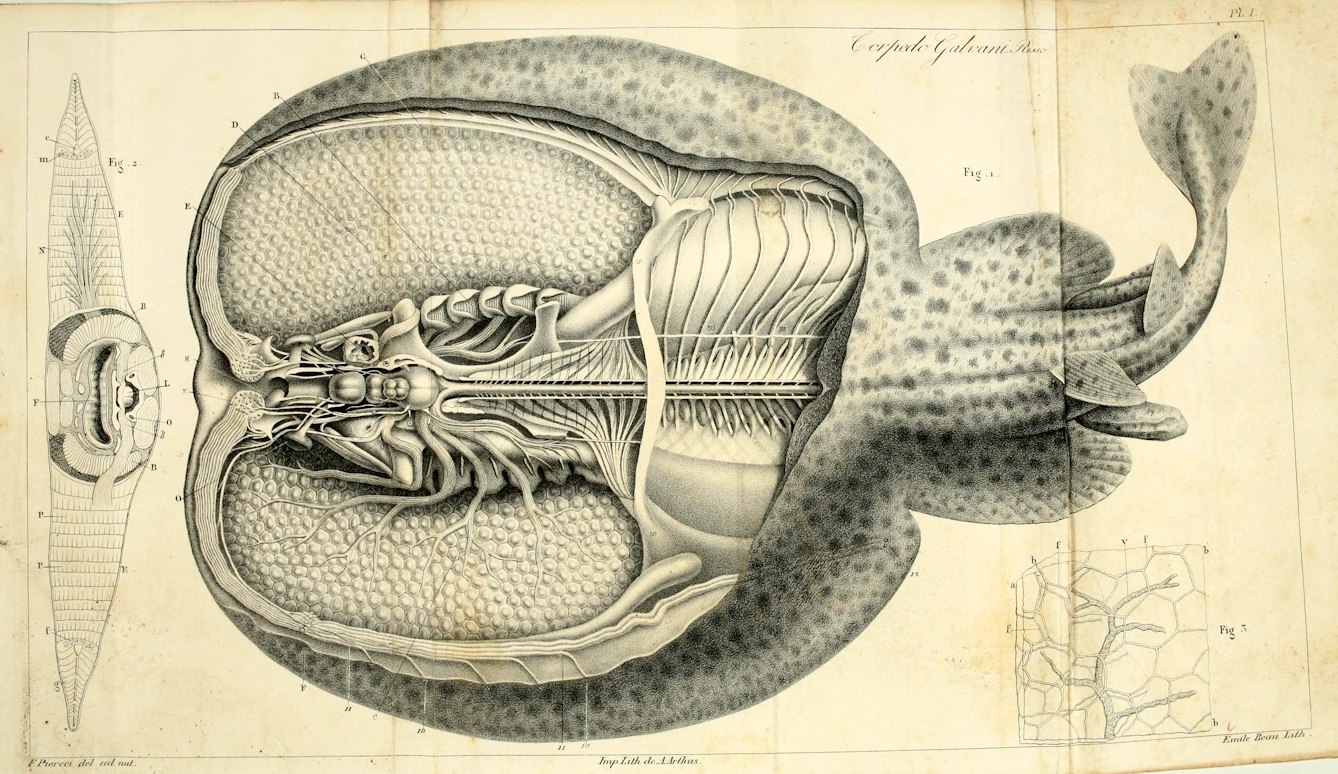

The honeycomb pattern of the torpedo’s electric cells can be seen to each side of its head.

French naturalist Georges Louis Leclerc Buffon’s sumptuous illustrations aimed to be an accurate record of nature.

Carlo Matteucci’s treatise was one of the most important studies of animal electricity of the 19th century.

Electricity loomed large in the work of Louis Figuier, one of the most prolific science popularisers of the 19th century.

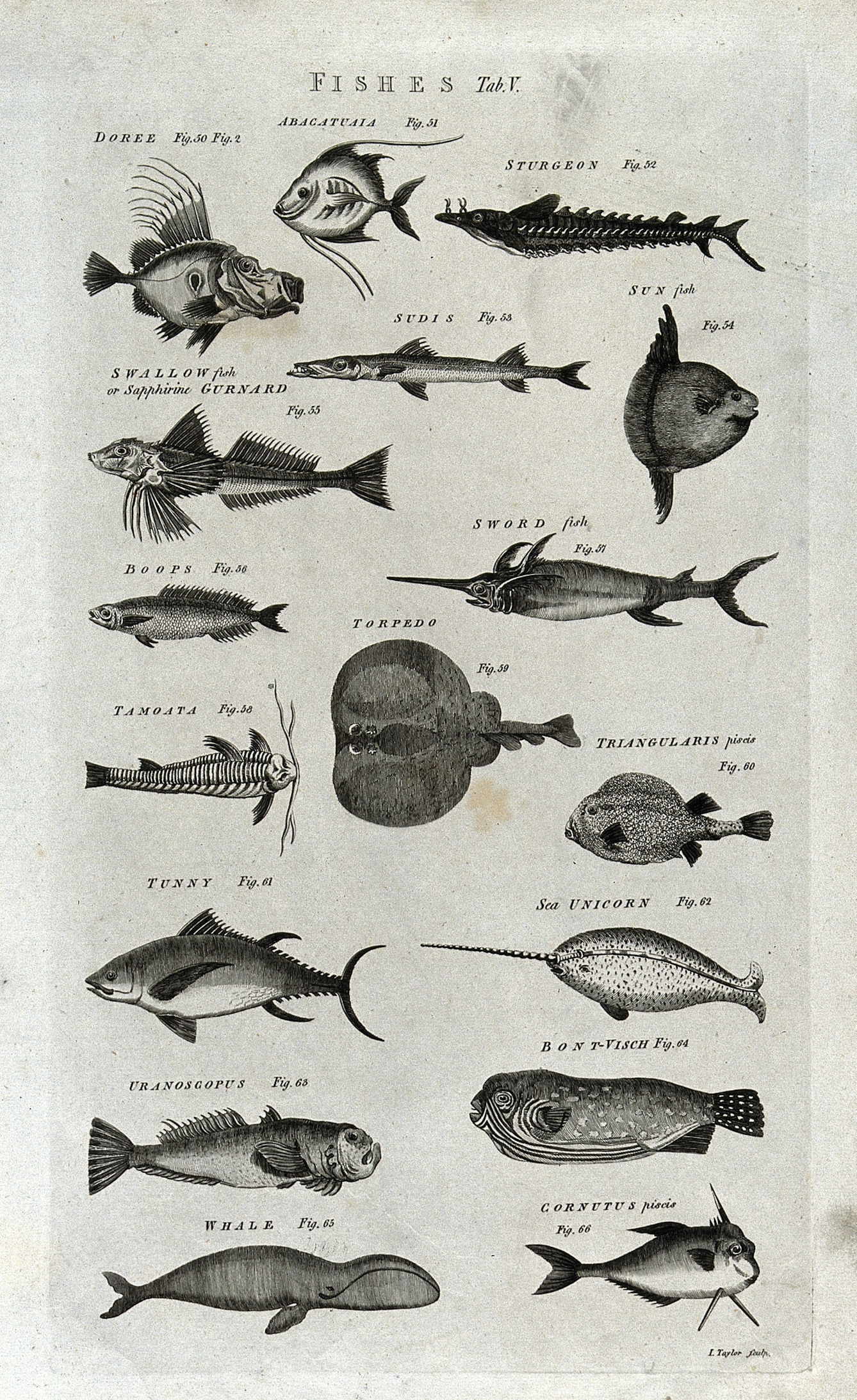

‘Seventeen fishes; including a sturgeon, sword fish, narwhal and whale’. Engraving by I Taylor.

Electric fish exerted a powerful hold on natural philosophers, who were faced with intriguing conundrums: how could creatures generate, store and discharge electricity without doing themselves harm and, moreover, in an aquatic (and therefore conductive) environment? Naturalists such as the American Edward Bancroft and the Prussian Alexander von Humboldt travelled to South America to study electric eels in their native environment. The exoticism and mystery of these creatures was only enhanced by their origins: Guyana, a Dutch colony whose rivers and ponds were home to electric eels, was also believed to be the site of El Dorado, the legendary city of gold.

The electric eel was a centrepiece of electricity demonstrations in 18th-century London.

By the 1770s the first electric eels were being shipped to North America and London, where public demonstrations of their electrical properties were immensely popular (for anybody who could afford the prohibitive entrance fees). Advertisements for the displays offered the sensational opportunity to experience “electric strokes” at first hand. One experiment involved several audience members joining hands while one touched the eel with an iron rod, thereby transmitting a violent shock to the whole group.

Eel impresario George Baker held his exhibitions in Piccadilly, near other exotic animal attractions and menageries, attracting elite visitors including the Duke of Devonshire, George III, and his wife, Queen Charlotte. The popularity of Baker’s spectacles led to him being “obliged to draw the spark or vivid flashes from [the] fish but three times a week… on account of the danger of their being exhausted by the too repeated experiments of every day”.

If audiences were enthralled by the displays of sparks and the experience of physical shocks from these exotic creatures, they were also titillated by an erotic undercurrent, which prompted a slew of near-pornographic literature where the electric eel was once again centre stage.

A connection already existed between the electrical ‘spark’ and sexuality. The erotic potential of the electric eel as a phallic stand-in was too conspicuous for writers and satirists to ignore. Unsurprisingly, the more sinister aspect of the eel’s erotic charge was offered up by the infamous Marquis de Sade, who deployed the electric eel as an instrument of torture on female victims in his 1795 work ‘Philosophy in the Boudoir’.

The English poet James Perry took humorous advantage of the eel’s suggestive symbolism in several extremely lewd, satirical poems, almost certainly inspired by contemporary scientific experimentation and public demonstrations. ‘The electrical eel, or, gymnotus electricus’ tells the story of Eve’s seduction by the serpent in the Garden of Eden. The poem’s ribald sexualisation of the eel is none too subtle:

“Till from the pond the lengthen’d Eel,

Bewitch’d, began her pow’r to feel,

And from the mud he grew.

He grew erect – he won her eyes,

Both by his sleekness and his size…

Th’electrick fire soon warm’d her heart,

The fire to all she did impart,

And nature own’d the feel:

From that gay period up to this,

The Wife, the Matron, and the Miss,

Hallow’d th’Electrical Eel.”

The Gymnotus electricus was a staple in the 18th-century craze for electrical demonstrations, but natural electricity was by no means the only draw. A wide variety of entertainments featured artificial electricity: flying boys attached to electrostatic machines, necromantic cats emitting sparks from their tails, and electrifying kisses. All provided similar thrills for a public both hungry for spectacular sensation and willing to put their own bodies into the limelight.

About the author

Ruth Garde

Ruth Garde is a freelance curator and writer, focusing on the fields of history, art, architecture and heritage. Over the past fourteen years she has worked extensively with Wellcome Collection, writing and curating a variety of projects encompassing history, human health, art and science.