Like nearly all of us, novelist and poet Daisy Lafarge was unable to travel in spring 2020. But a new microscope afforded her a view of another world: that of the miniature creatures living in drops of pond water. Her visits to this alternative universe became an escapist ritual during a period of enforced isolation.

Before all this, the 2020 of my mind was filled with travel and vegetating animals. It was the last year I would have access to the small grant that came with my PhD, the compromising kind where you pay up front and invoice later, to be used strictly for travel costs incurred for research. My plans included visiting the Station biologique de Roscoff in Brittany, where I had hopes of seeing Symsagittifera roscoffensis, a species of tidal flatworm that spends its time moonlighting as seaweed on sandy Atlantic beaches.

S. roscoffensis, also known as the Roscoff worm or mint-sauce worm, was of interest to late-19th-century biologists, who observed that the tiny, bright green worms appeared to be filled with a chlorophyll-like substance. But that couldn’t be right, they thought, because Plantae formed one branch of life, and Animalia another; animals don’t photosynthesise.

Not until Scottish polymath Patrick Geddes – then stationed in Roscoff as a 24-year-old student of marine biology – discovered that, actually, some do. He noted that the abundance of worm colonies in shallow pools during fine weather was “very striking”, and through a series of experiments was able to determine that the Roscoff worms did indeed photosynthesise, and concluded that they “may not unfairly be called Vegetating Animals”.

I’d hoped to spend a few days of spring 2020 with these vegetal animals myself, but as March turned into April, all these plans were pushed into the anxious, indeterminate future. A novel pathogen was circulating, and during those early days in the epidemiological dark, intense scrutiny of unseen, microorganic life was becoming a fraught part of day-to-day existence.

“A month or so into the first lockdown I used the travel grant to purchase a beginner’s microscope – ‘perfect for kids and students’.”

There was plenty of cause for paranoia in my personal life, too, and somehow, in the midst of all this, I thought it would be a good idea to get a microscope. I couldn’t get to the Roscoff worms, but maybe, I thought, I could find an approximation closer to home.

A living stained-glass window

A month or so into the first lockdown I used the travel grant (with some persuasion) to purchase a beginner’s microscope – “perfect for kids and students”, as the online description put it. On my government-sanctioned daily walks to nearby city parks and woodland, I collected water from ponds, pools, bodies of stagnant water, puddles in the cavities of tree trunks.

This new-found attention to water – its places and qualities – became a ritual in itself, affording me a rhythm and focus outside of my thoughts and fears. The next stage of the ritual took place at my kitchen table, where my microscope was set up. I would begin by placing a drop of water on a glass slide, and soon lose myself to hours of enraptured observation, witnessing life – which seemed oblivious to the world raging around it – unfold on the slide.

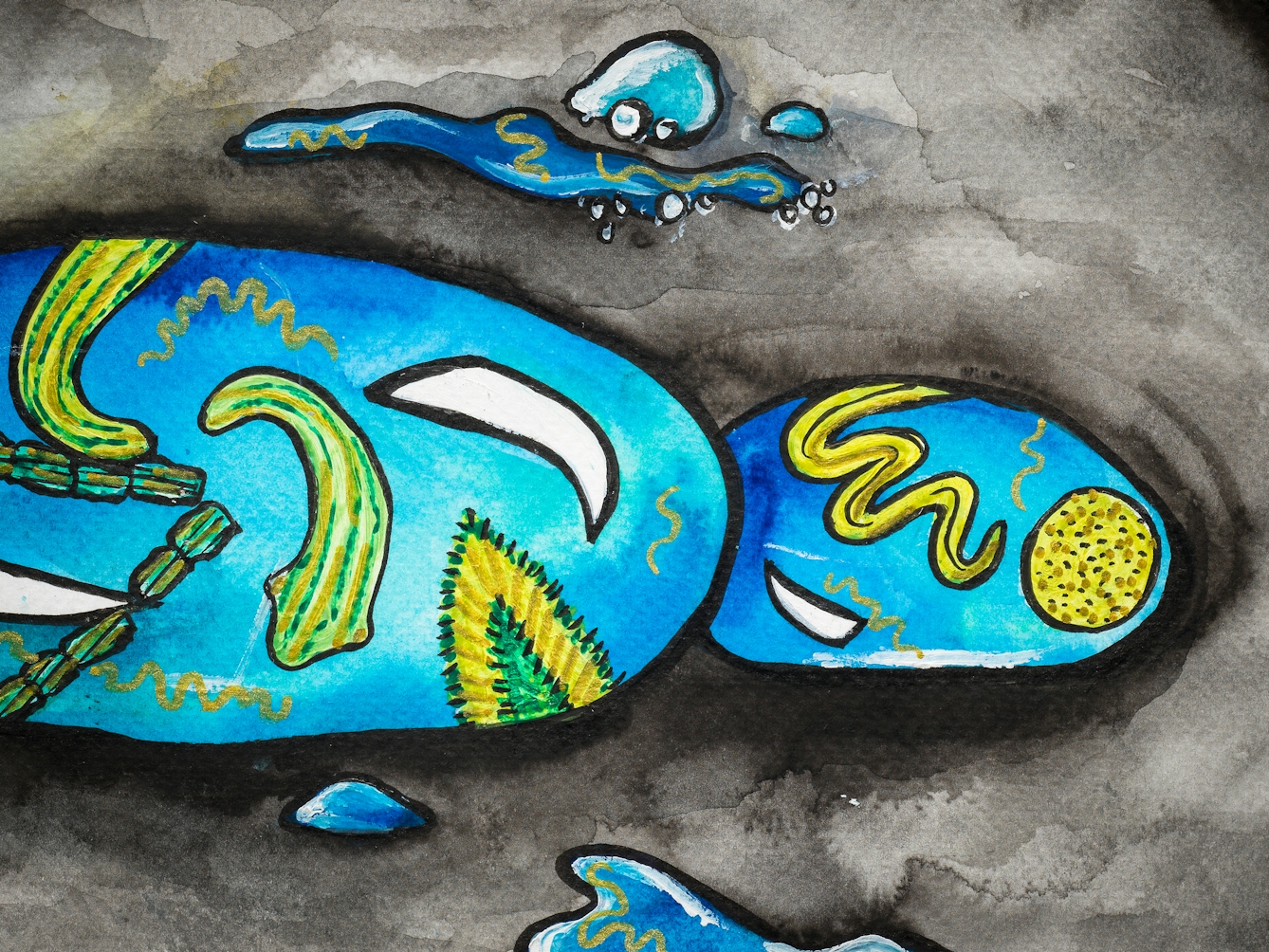

The pond-water samples were my favourite – each drop was a living stained-glass window, an impossibly wrought lattice of green and gold. Slowly I began to identify what I was looking at: the gliding thumbprint bodies of flatworms, coils of filamentous green algae, fanged insect larvae and crystalline diatoms.

In one fortuitous sample from a swampy part of my local woods, where the red soil is staked with field horsetail and the shallow water capped with a mercury-like meniscus, I found tangles of Vorticella, bell-shaped ciliates whose glitchy movements rank them among the fastest-moving organisms.

“I would begin by placing a drop of water on a glass slide, and soon lose myself to hours of enraptured observation, witnessing life unfold on the slide.”

Mostly I felt I had passed through into another world. In ‘Drops of Water’ (1851), a guide to amateur microscopy by the 19th-century scientist Agnes Catlow, I found a good description of this ethereal transportation:

“My readers must fancy themselves spirits, capable of living in a medium different from our atmosphere, and so pass with me through a wonderful brazen tunnel, with crystal doors at the entrance.”

For me, the ritual of microscopy is something that could only have come out of that time when it seemed as though the world had stopped turning.

I felt as though I was peeking through a crack in the crystal doors and I never wanted to look away. Keen as I was to learn about the minute inhabitants of water, I also knew my motivations were more meditative than scientific. For me, the ritual of microscopy is something that could only have come out of that time when it seemed as though the world had stopped turning, and we all began living in an atmosphere estranged from the one we had known.

As for the vegetating animals, my approximation arrived surprisingly early on. My lens was focused on the translucent body of a mosquito larva, its segments expanding and contracting as it munched on something out of view. As a result, I paid little attention to the slow-moving blob of green that drifted into sight, and stayed put when the larva slithered away a minute or so later. The green thing was unassuming at first, but the closer I looked, the more it seemed to glisten, as if filled with emerald sand.

“I felt as though I was peeking through a crack in the crystal doors and I never wanted to look away.”

Some weeks later I would identify this as Paramecium bursaria, a single-celled ciliate filled with endosymbiotic cells of algae. These Zoochlorella algae live in the Paramecium’s cytoplasm and provide it with food via photosynthesis, while the Paramecium affords the algal cells greater movement and protection. The emerald sand was symbiosis – or what Geddes called “reciprocal accommodation” – in action, one species living inside another; my makeshift Roscoff worms.

Community life in miniature

In her preface to ‘Drops of Water’, Catlow introduces an unnamed microorganism (possibly the globe algae Volvox) as a community:

“…it is not one being alone, but is formed of hundreds of minute beings, all enjoying life, and grouped together in this curious manner for mutual support.”

In this “mutual support” I couldn’t help but hear an echo of “mutual aid”, and I wondered if my attraction to the anarchic sublime of life and liveliness in the pond water was connected to the enforced isolation of lockdown. I was craving the company of other organisms, and life in a drop of water was as close to a crowd as I could get.

During a time of fear and revulsion towards microscopic life, I was grateful for these encounters with the micro-non-human, and the reminder that wonder is not predicated on travel or expertise. When I shared the first images I had taken from my microscope on social media, mentioning the (now unusable) travel grant, a poet commented, as if channelling Agnes Catlow: “This is travel.” I would have to agree.

About the contributors

Daisy Lafarge

Daisy Lafarge was born in Hastings and studied at the universities of Edinburgh and Glasgow. Her collection of poetry ‘Life Without Air’ (Granta Books) was shortlisted for the T S Eliot Prize 2020 and was recommended by the Poetry Book Society. Her debut novel ‘Paul’ received a Betty Trask Award, and was published by Granta Books in August 2021.

Maïa Walcott

Maïa is a Social Anthropology undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh and a multidisciplinary artist working with sculpture, painting, illustration and photography. Her work has been widely published and exhibited, appearing in the anthology ‘The Colour of Madness’ and as part of ‘Project Myopia’. Maïa was also the in-house illustrator for the literary magazine The Selkie, and photographer for photo exhibitions such as ‘The I'm Tired Project’ and ‘Celestial Bodies’.