Jaydee Seaforth was brought up to downplay pain and to hide any emotional suffering. On top of that, her experiences of medical treatment reinforced her perception that Black women are supposed to be innately strong. But her body had other ideas, and she eventually learned to take note of them.

Don’t call me a strong Black woman

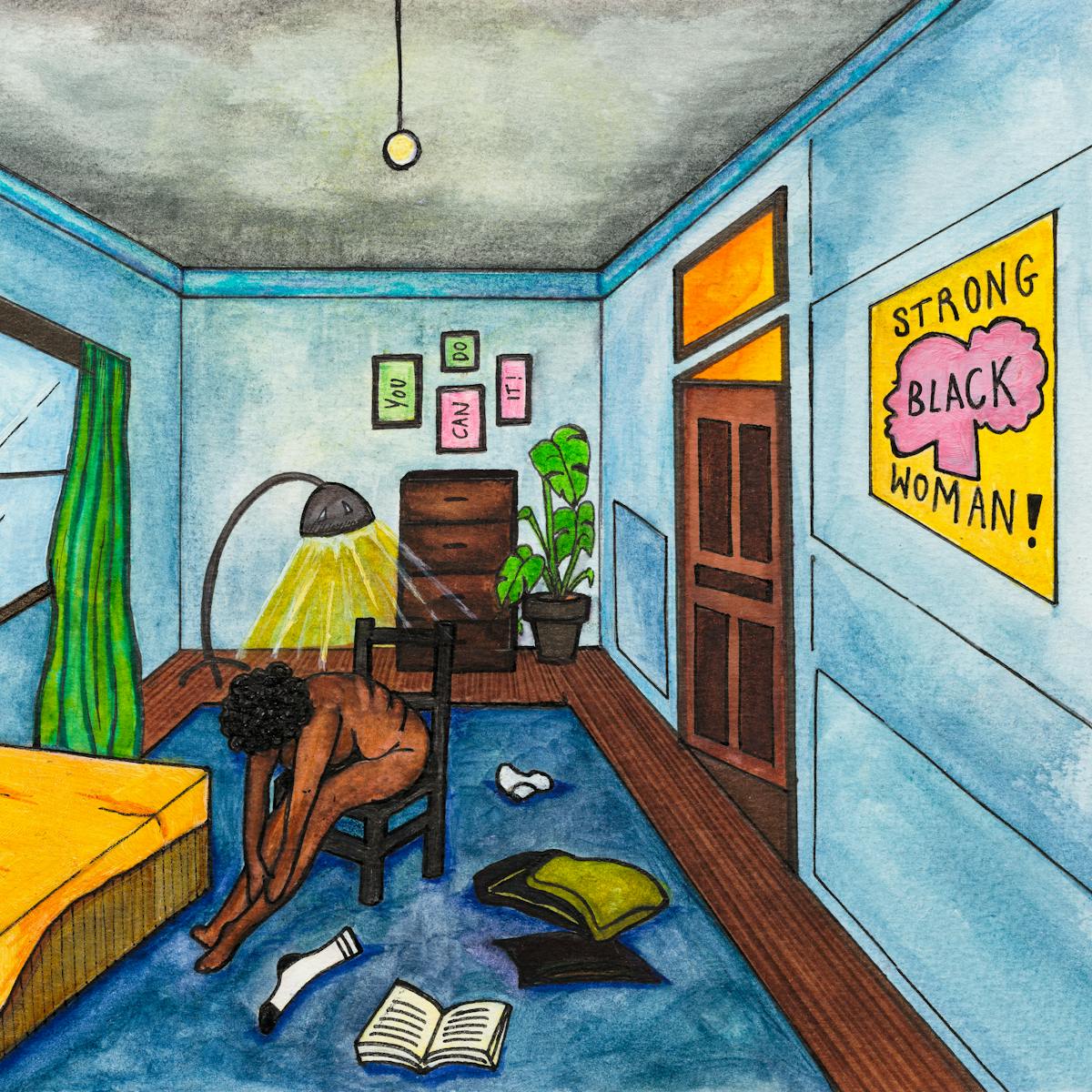

Words by Jaydee Seaforthartwork by Maïa WalcottBlack Balladaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

I was raised to be so strong that when I awoke after a failed overdose, I hoisted my body up, kicked the remains of the vodka-pill concoction I had consumed under my sweat-soaked bed, and in a daze, found myself in my university library.

My recollection of how I arrived there is as foggy as it was on that day. However, I do remember making one phone call.

I was too strong to reach out across the hall, to collapse into the arms of a friend I had known since plimsolls came back into fashion. No, strength meant detachment. So, sick to my stomach at the thought of such vulnerability (and probably also due to the damage the pills were doing to my kidneys), I called another friend.

Through muffled tears I explained what I had done. The contents of the conversation remain a blur, but her words lifted me out of my room, into the daylight and onto our university campus. More than I had been able to do for myself in weeks.

I was so strong that I spent the whole day in that library – laughing, entertaining, and at times I’m sure it probably looked like I was actually even studying. But every now and then I’d glance at the friend I had confided in, see the concern fog up her eyes, and I’d have to leave the desk.

“I was too strong to reach out across the hall, to collapse into the arms of a friend I had known since plimsolls came back into fashion.”

Hiding my pain

You see, crying was reserved for bedrooms or bathrooms, alone. My parents taught me that. I was to “go to my bedroom with all that noise” or I’d be given “something to actually cry for”. Through that common threat of violence, I not only learnt that pain is solely a physical phenomenon, but I needed an authority figure’s permission in order to feel.

It wasn’t enough to take my own body, my own emotions at their word. Whether I could cry, feel sadness, anger, disappointment or even joy was dependent upon the instruction of the adults around me. I was often told to “fix my face”, effectively outlawing any display of emotion that signalled discomfort.

Which meant that at the age of 11, I walked around for a day and a half with a chip in my patella (kneecap), before rounding off the evening with a gymnastics class. My mum (a gymnastics coach) made sure to let the other coaches know, not that I was injured, but to not believe me if I said that I was. I would only be using it as an excuse to get out of doing tasks.

It was only after a cartwheel landing went wrong, and my inability to stand, that someone finally checked my knee. At this point, it had swollen to the size of a small grapefruit. I still remember my mum calling from across the room demanding I stop the theatrics and stand. I also recall the shooting pain that ran up the length of my left leg as I tried.

My mother was preparing me for a health system propped up by the same foundational beliefs – Black girls do not feel pain.

“My mother was preparing me for a health system propped up by the same foundational beliefs – Black girls do not feel pain.”

What is strength if not endurance, and what is a Black woman if she cannot endure?

This conspiracy that within Black women resides an unlimited well of strength did not start with my mother. We can root it back to slavery, to talk about the Black woman’s ‘ability’ to take the whip just as well as the Black man. Or back further, before White people decided Black women were strong. To our warrior ancestors, but for whose ability to endure, I wouldn’t be here. Because what is strength if not endurance, and what is a Black woman if she cannot endure?

So, I rooted my identity in how much I could bear and carried my mother’s mantras with me: “We’re stronger than other people, Jay,” “We don’t get depressed, we get on.” And so I got on and didn’t stop until my body saved itself.

Black women are human too

My relationship with our beloved NHS has been one dictated by fear. I watched helplessly as my mother lay in hospital with her fallopian tubes twisted, while doctors and nurses questioned her pain levels, her fidelity to my father, and whether her writhing was due to drugs.

When my mental health issues began to manifest in the form of burnout, and a seemingly sporadic skin condition, I was reluctant to call the GP. My mother’s experience and the countless experiences of Black women just like her taught me that even when Black women say they are weak, they are regarded as strong. Our own internalised ideas of strength and our performance of it renders us unable to perform pain in the ways expected of women.

When I eventually built up the resolve to speak with a doctor, I spent most of our consultation downplaying my symptoms.

“I decided then that I would no longer perform strength for the benefit of others.”

Along with strength, I was also raised to have shame. And for a Black woman to say “I need help”, for me was a very shameful thing.

Instead, I lied about the frequency I left the house, how often I managed to bathe and clothe myself. I didn’t even mention the skin issues. When the doctor told me I was fine, I believed him. Until I started to begin to feel as I did that day at the library.

So I went back, and this time I was honest. He took notes, checked my skin with a stumped look and when it was all over, he told me once again that I was fine. I didn’t have depression; I had a low mood, at best. And as for the skin? Meh. It wasn’t painful, would probably clear up on its own.

It wasn’t until I was mindlessly scrolling on Twitter weeks later that I found my sporadic skin condition was actually hives. A Black woman had made a video showing what hives look like on darker skin and I started to well up. I know, not very “strong Black woman” of me.

I was frustrated at the fact that we’re still in a place where white skin is seen as the default, so much so that the doctor couldn’t fathom that something so common could be happening to me. But I was also emotional because I was still that little girl waiting to be told if she was allowed to be in pain or not. I decided then that I would no longer perform strength for the benefit of others.

Now I listen to my sole authority: my body. I put her needs before the needs of the community, because I am aware that I cannot draw from an empty well and that wellness cannot exist without honesty. I have accepted that though my well may be deep, it is not bottomless. And that doctors don’t always know what they’re talking about.

In partnership with

Jaydee Seaforth

Jaydee Seaforth is a multidisciplinary writer and educator from south London. She has written for publications such as Black Ballad, BBC3 and Oxford University-founded print magazine Onyx! With an interest in activism, social injustice, and all forms of human interaction, she aims to make you feel less alone.

Maïa Walcott

Maïa is a Social Anthropology undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh and a multidisciplinary artist working with sculpture, painting, illustration and photography. Her work has been widely published and exhibited, appearing in the anthology ‘The Colour of Madness’ and as part of ‘Project Myopia’. Maïa was also the in-house illustrator for the literary magazine The Selkie, and photographer for photo exhibitions such as ‘The I'm Tired Project’ and ‘Celestial Bodies’.

Black Ballad

Black Ballad is a digital-media lifestyle platform and membership community for Black women in the UK and beyond. Through content, events and community, they exist to empower every Black woman to realise how she can change her world through every click she makes and every conversation she has.