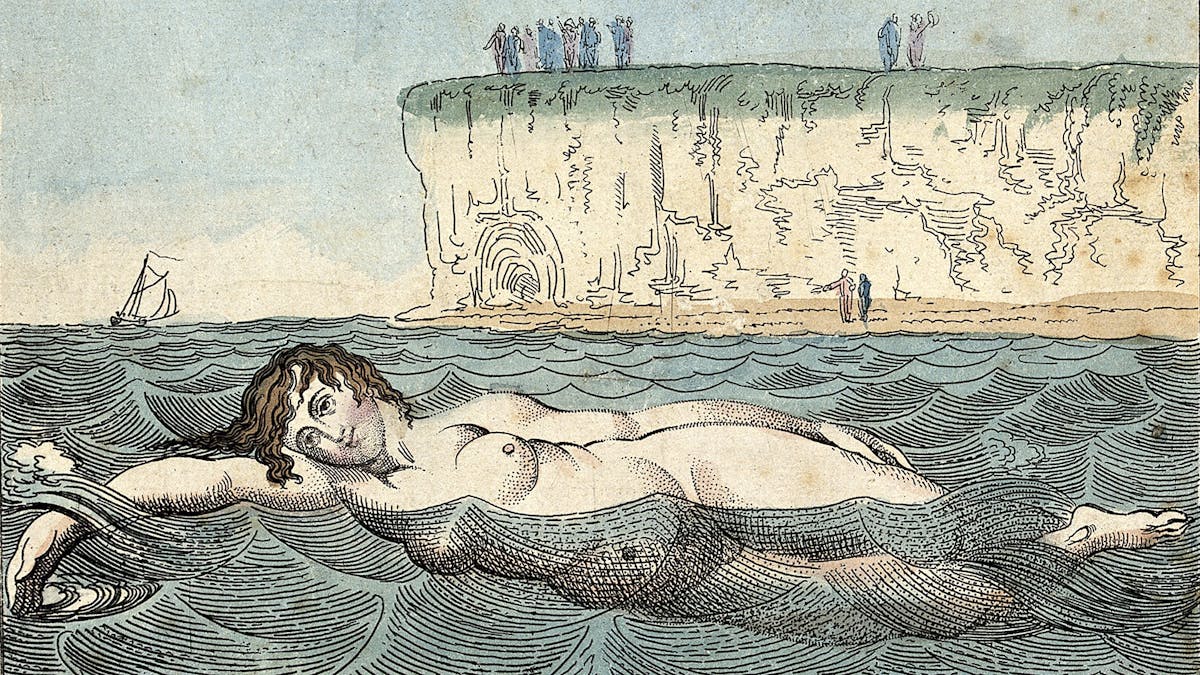

Fashionable seaside towns in England owe much of their popularity to the 18th-century doctors who advised their patients to take the ‘sea cure’.

How did the so-called ‘sea cure’ supplant the taking of waters at fashionable spas for Georgian England’s worried well? This was the question I sought answers for in the Wellcome Library. There, I found several intriguing medical tracts, not to mention highly entertaining images, which shed light on all aspects of this new craze for sea bathing.

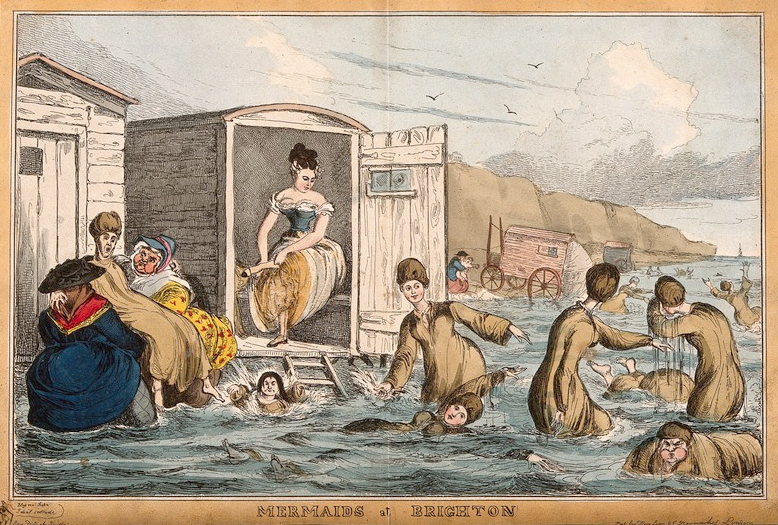

Mermaids at Brighton by W Heath (1905-1840). Fashionable women flock to take the ‘sea cure’ at Brighton, with its bathing machines scattered along the seafront.

The Library has a first edition of a book by Sussex doctor, Richard Russell, entitled ‘A Dissertation Concerning the Use of Sea Water in Diseases of the Glands(view in catalogue)’ (1753). In it, he gives the case histories of numerous patients who reported spectacular improvements in their health after bathing in the sea in nearby Brighton. For example, he treats with seawater a farmer’s wife who complained of colic. Over a period of time, she “voided 300 stones”. And two years later, she was “delivered of a healthy child”, whether directly attributable to the powers of seawater or not, he doesn’t say.

Fashionable resorts

Other doctors were quick to jump on the bandwagon, recommending trips to the seaside for almost any condition. Along the south coast in particular, sleepy fishing villages were redeveloped as seaside resorts as patients flocked to their shores. Who would have guessed that this serious medical book would have such an impact, not just on medicine but also on the economy of coastal towns? Russell certainly didn’t.

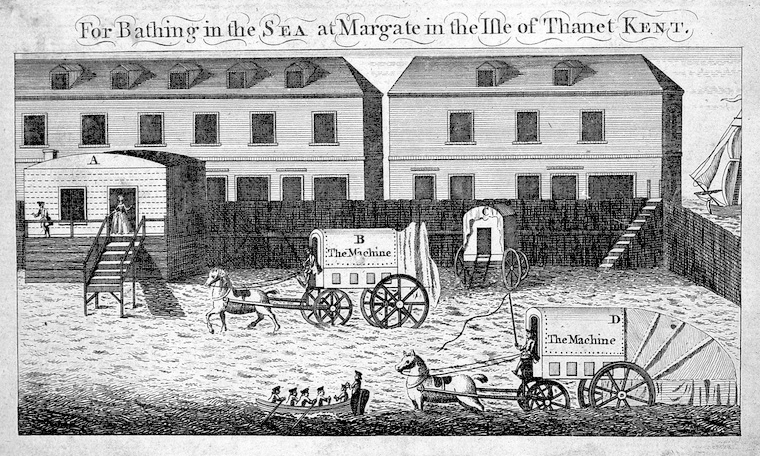

The bathing enclosure at Margate, Isle of Thanet, Kent, containing several bathing machines and a bathing room.

Physicians obviously had a vested interest in insisting that patients took professional medical advice first. At a traditional spa town, ‘taking the waters’ meant both bathing in and drinking the water. You wouldn’t have been surprised then, if your doctor encouraged you to drink seawater as well. But you could dilute it with milk if you didn’t like the taste. It’s a relief to note that this practice dropped out of fashion.

Medical opinion on a range of seaside-related issues varied considerably. A Dr Robert White – who, in 1775, published ‘The Use and Abuse of Sea Water Impartially Considered(view in catalogue)’ – gives dire warnings to anyone who attempts an unsupervised cure. He reports that several of his patients who wilfully ignored him ended up dead.

A healthy diet

Then there was the matter of diet. The Wellcome Library has a tiny, cheap-looking pamphlet, dated 1798, by one Dr Squirrell. He advises extreme caution about the whole thing, but for anyone hell-bent on taking to the sea, he recommends “a proper dose of Tonic Powders”. By coincidence, at the back of the booklet, there’s an advertisement for just such Tonic Powders – prepared by Dr Squirrell himself.

Another doctor criticised those fellow professionals who encouraged patients to starve themselves before bathing. He recommends a “good nourishing diet” of meat. Fruit and vegetables, obviously, are dangerous and should be eaten sparingly. One of his female patients, he says, “was thrown into the most violent pain, and spasmodic convulsions of the stomach” by nibbling fruit.

Alcohol, on the other hand, is clearly beneficial. “We may venture to lay it down as a rule, without exception,” he writes, that “the moderate use of strong liquors … necessarily make a part of the regimen to be observed throughout the cure” – “beer, spirits diluted with water, or wine cannot do harm”.

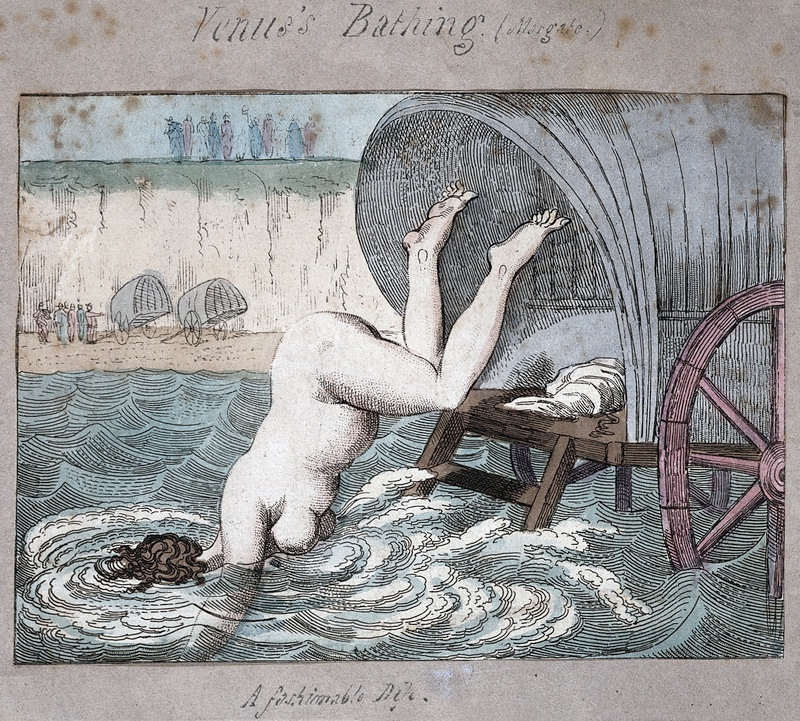

Venus bathing (Margate) – a fashionable dip. Coloured etching by Thomas Rowlandson (1756-1827).

Seaside etiquette

I then decided to investigate the nitty-gritty of the seaside dip. What did you wear? Did you actually swim? And who were these ‘dippers’ the doctors wrote of? Answers to these questions lie in a range of revealing 18th- and 19th-century prints, including some fabulous Thomas Rowlandson caricatures.

‘Dippers’ feature in many cartoons, cheerful-looking men and women up to their waists in water, whose job it is to encourage, or frequently push, bathers beneath the waves.

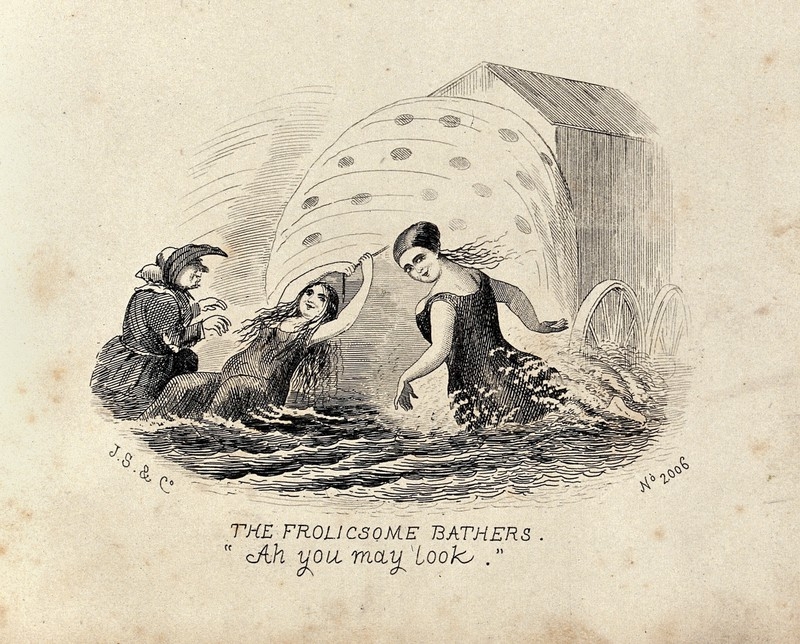

The “frolicsome bathers” emerge from their bathing machine, only too aware that they are being observed: “Ah you may look” says their glance! Standing beside them is a fully dressed woman, the ‘dipper’ with her arms extended, ready to dip them in the water.

In the Georgian prints, the bathing machine is the only seaside technology (deckchairs have yet to be invented). These sort of horse-drawn beach huts in which bathers could change seem to provide endless amusement. A Quaker, Benjamin Beale, invented a cloth awning so that modest females would be protected from sight. But several of the more saucy images suggest that not all women bathers worried too much about being seen – even when clifftops abound with gents wielding hired telescopes.

It all looks rather too much fun. One suspects that the doctors were losing the battle to control the seaside.

About the contributors

Jane Darcy

Dr Jane Darcy is an Honorary Lecturer in the Department of English at University College London.