As her family moved around the UK with her father’s work, Ishani Kar-Purkayastha made and lost a series of tentative friendships. She worried about inviting children from school to her house, which was temporary and impersonal, not something she saw as representing her. While at the time she felt she had no true home, today her past presents a different perspective.

When Michelle spoke about inviting me round to hers for tea, I used to worry about when it would be my turn.

Michelle was the girl I talked about when well-meaning adults asked me who my best friend at school was. In truth, she was just my “sort-of-a-friend”. She already had a bestie: Penny. Together since nursery, like everybody else at school, they had ten years behind them, to my year and a half.

Still, Michelle was curious, and kind. She took a liking to me and even persuaded Penny to accept me, to the point that I might name them both as “sort-of-friends” if pressed.

A house that’s not home

Unlike me, Michelle’s house was her home. She had decorated her room with dandelion wallpaper. She had one of those beds with a desk underneath, a lava lamp, a lavender shag-pile rug and a poster of the Pet Shop Boys on her wall. She had a dog called Milo.

I worried that if she or Penny ever came round to my house, they would perceive a version of me that I kept from school, mistaking the two-up two-down, brown-brick semi-detached box for a home that my family had chosen, rather than just the house assigned to us, and I would seem even more different from them than I already was.

“Number two Helensborough Close was where I lived, but it was not a home. It wasn’t of me, it didn’t represent me.”

It wasn’t the size of house that mattered, or the brick. It was just that from the outside, number two Helensborough Close was exactly the same as numbers four and six and eight, from the colour of the doors to the window frames, the grey driveways and flat, shale-roofed garages. On the inside, the walls were always a buttery magnolia, and the carpets a dull, scratchy beige.

Number two Helensborough Close was where I lived, but it was not a home, not in the way Michelle or Penny had a home. It wasn’t of me, it didn’t represent me.

Medical staff on the move

Along with all the other houses in that cul-de-sac, number two was “hospital accommodation”. Located across the main road from the gleaming concrete mass of the district general hospital, it was part of the NHS estate used to house the many doctors and nurses who came from abroad to work in the UK.

The NHS has a long history of recruiting clinical staff from overseas. Those who came in the 1970s and 1980s, by invitation from the British government, did so for different reasons, caught in the consequences of colonialism and the propaganda of the Commonwealth – opportunity, employment, qualifications.

My father came because in those days, training in the UK and acquiring membership of the Royal College of Physicians was an endorsement that would set him apart from his peers. Some stayed, but there were many like him who coveted those letters, and came just so that they could return with framed certificates that they could then hang with pride on walls behind desks in doctors’ chambers all over the world.

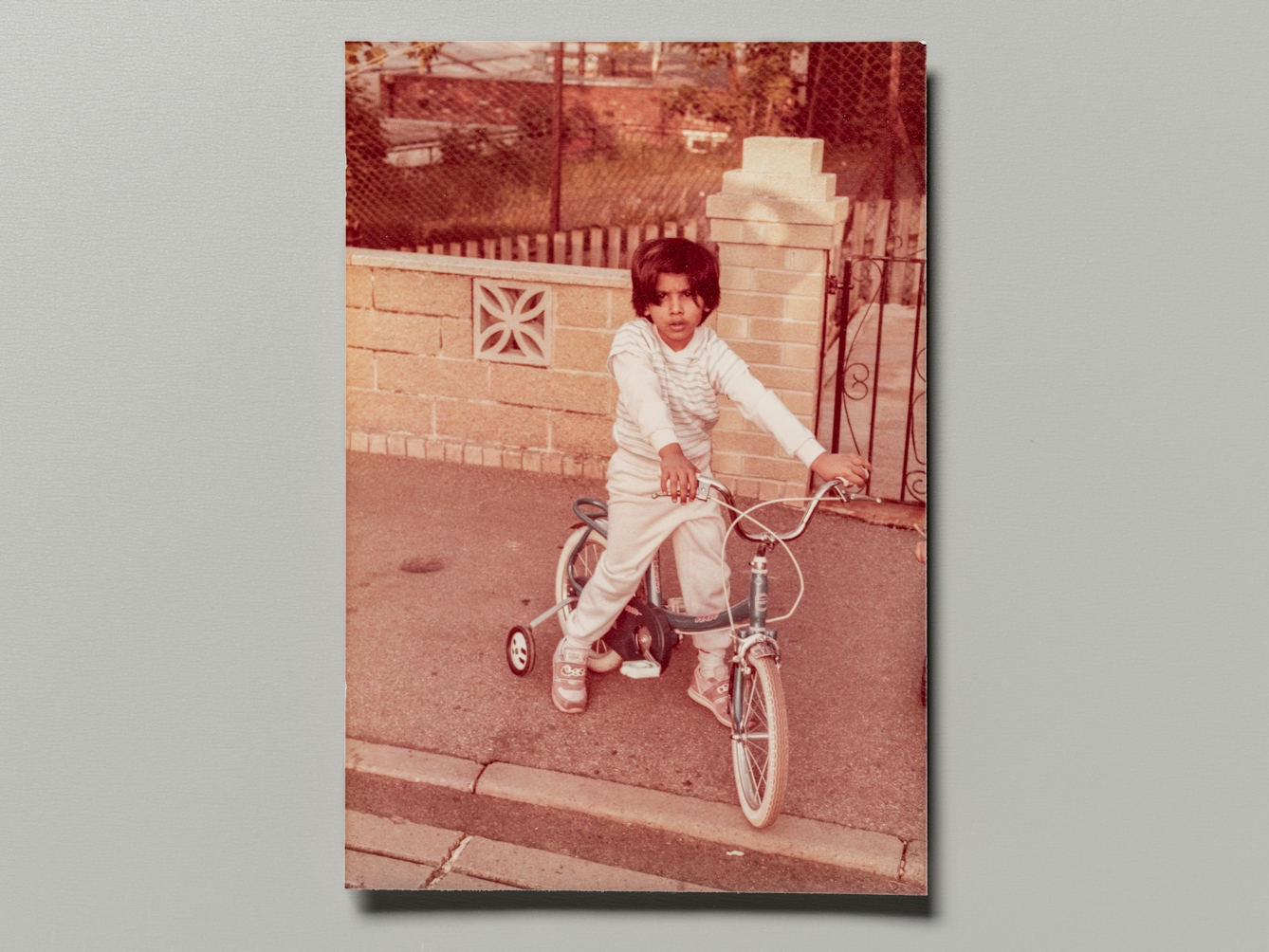

“Within those cul-de-sacs, we were free, secure. We raced on our bicycles without inhibition or any expectation of permanence.”

Back then, my parents didn’t feel any need or desire to be tied to the land, to own a piece of Britain. Home was somewhere else. For my father, it was a tea garden at the foothills of the Himalayas, in a country that was lost to him through the Partition of the Indian subcontinent. He could not go back there, but he would get as close as possible. For my mother, home was with her family.

There were practical reasons as well. Immigrant doctors didn’t have the same access to training opportunities as local graduates, and so every couple of years we moved. We changed towns, mostly across the North of England; I changed schools, made new “sort-of-friends” who I knew I would leave behind.

Consistency and community

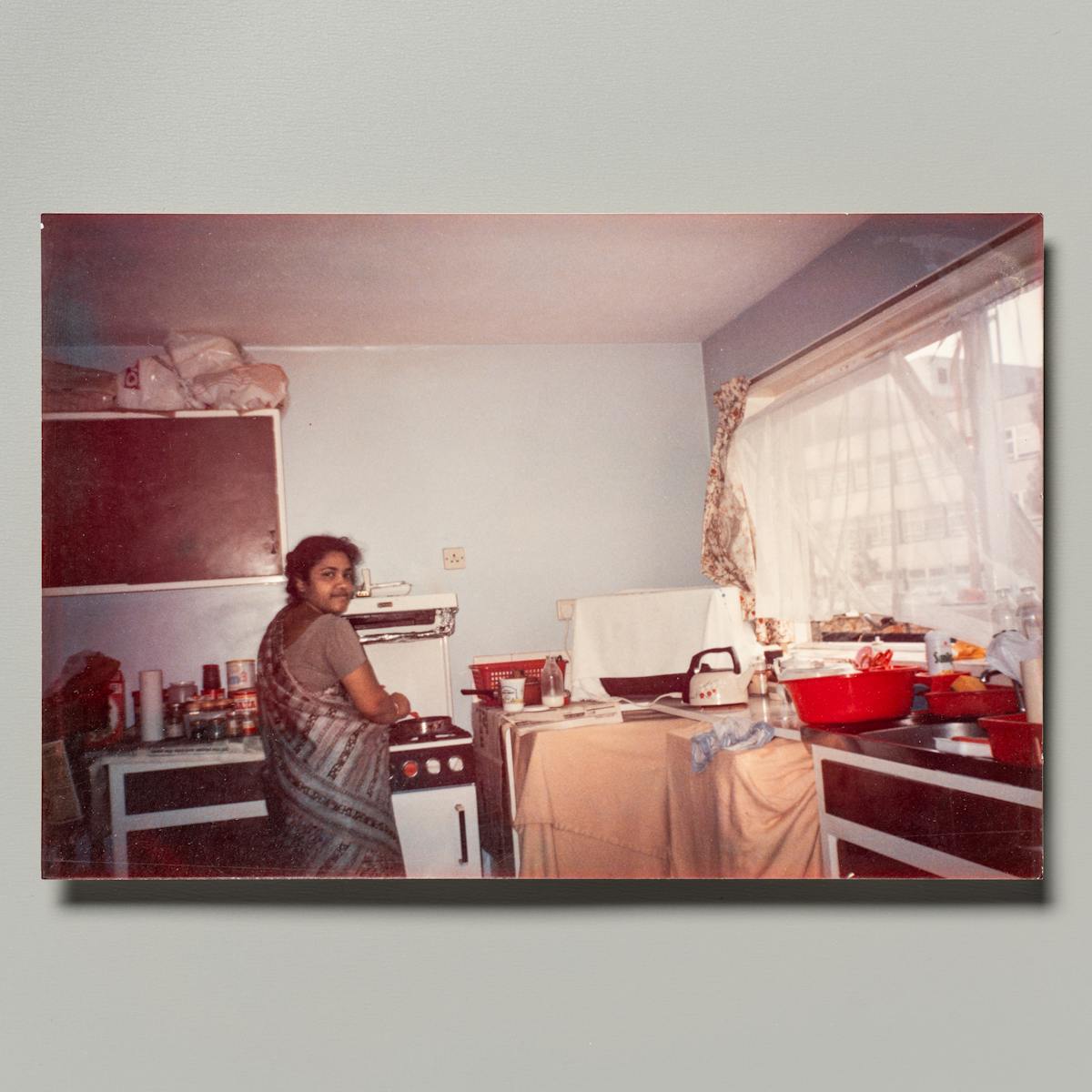

The only thing that remained constant was that wherever we went, it was always to a colony of immigrant workers, under the auspices of the hospital. We lived interchangeably, with doors wide open, in one house or the next. We sat together on sofa-chairs all upholstered in the same easy-clean Rexine; we wiped our bodies on standard-issue towels and slept on bedsheets emblazoned with the blue NHS logo.

And from this coalescence of physical spaces, a new country was navigated, wisdom exchanged from rituals of pleases and thank yous, to the chit-chat of weather and issues of school admissions and what not to name your child.

We lived interchangeably, with doors wide open, in one house or the next.

It was here too, across many a shared mealtime on plain white NHS plates that could have been anybody’s, that a generation of immigrant doctors would make sense of medicine in another culture. At a time when provision of free healthcare at the point of need remained a burning light for many, even when sullied by everyday personal experiences of humiliation and injustice, it was here, in the safety of these communities, that they found a space in which to make sense of the NHS, in both its courage and cowardice; a space to understand and move on.

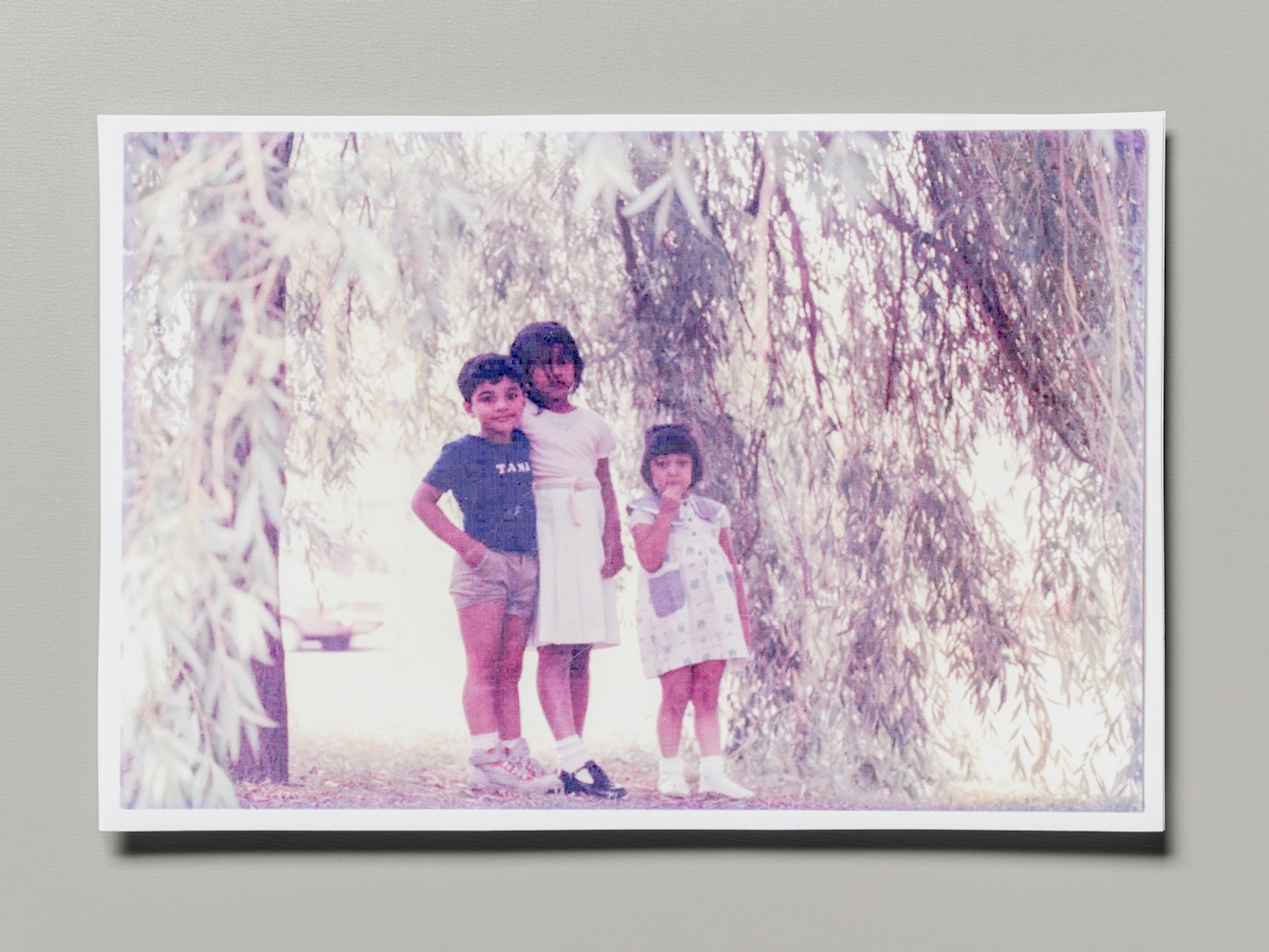

“We hung out underneath weeping willows. We made friends with children of all ages, all different shades of brown and black, accepting the flux, perhaps even embracing it.”

For me, Helensborough Close was the only place where I was the same as everyone else. Though we were from all over the world, we were united in our shared experience of being foreigners, immigrants. It was a place where we ‘others’ congregated – in an old country from a myriad of ‘lesser’ countries, rising from the ashes of not-so-distant colonialism. It was a place to be equals.

Within those cul-de-sacs, we were free, secure. We raced on our bicycles and hung out underneath weeping willows. We made friends with children of all ages, all different shades of brown and black, accepting the flux, perhaps even embracing it, building connections more easily, without inhibition or any expectation of permanence.

Funnily enough, we tended not to play together at school. It wasn’t just that we were spread across years and timetables, but rather an unspoken understanding that we weren’t the same outside as we were inside Helensborough Close. An understanding that though we had the community of each other, we also each had our own journeys to make, navigating shame and belonging and identity in the big world. For me, Michelle was part of that.

A home beside the hospital

I never went to Michelle’s house, nor did she ever come to mine. To be honest, it was a relief, because I didn’t want to have to explain why my home didn’t look like hers. I could have tried, but back then, we were all still figuring that out. Individually and collectively. When I say ‘we’, I mean ‘me’ – my generation.

We no longer ask, “Where are you from?” In those days, we were asked that all the time. It mattered. Back then, I was from India. There was no doubt about that, and my home was both a memory and a longing that I borrowed from my parents. It was for me imagined, part past, part future.

But when I look back, I wonder if perhaps there had also been a home for me back then, a home I was yet to recognise. A home not in the buildings, but in the confluence of people sharing a journey, at a time when countries new and old were redefining themselves, just as we were.

I find it now in my memories of those cul-de-sacs around the hospital, itself always lit up, signposted, a constant landmark in our lives, a sanctuary, almost, there among the rainbow children of immigrant families, where we played like kings.

About the author

Ishani Kar-Purkayastha

Ishani Kar-Purkayastha is a consultant in public health and a writer. Her work includes the novel ‘The Dancing Boy’, published by Harper Collins India, and ‘The Sky is Always Yours’, in ‘Too Asian, Not Asian Enough’ published by Tindal Street Press. She has also published narrative essays, including ‘An Epidemic of Loneliness’, which won the Wakley Prize in 2010, and ‘The Age of Miracles’ in The Lancet.