Like many disabled people growing up in the 1960s and 1970s, thalidomide survivors had to fight for a proper education. If they weren’t brought up in institutions, they were often viewed as objects of curiosity, encountering verbal and sometimes physical abuse, both at school and, as they grew up, in the world beyond.

Disability, education and prejudice

Words by Ruth Blueartwork by Hollie Chastainaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

There is no single story of growing up as a thalidomide survivor. Some lived in special institutions from an early age, largely growing up outside of mainstream society with other disabled children. Others lived with their families and were educated in special schools, and some managed to find a place in a mainstream school where there may have been few, if any, other disabled pupils.

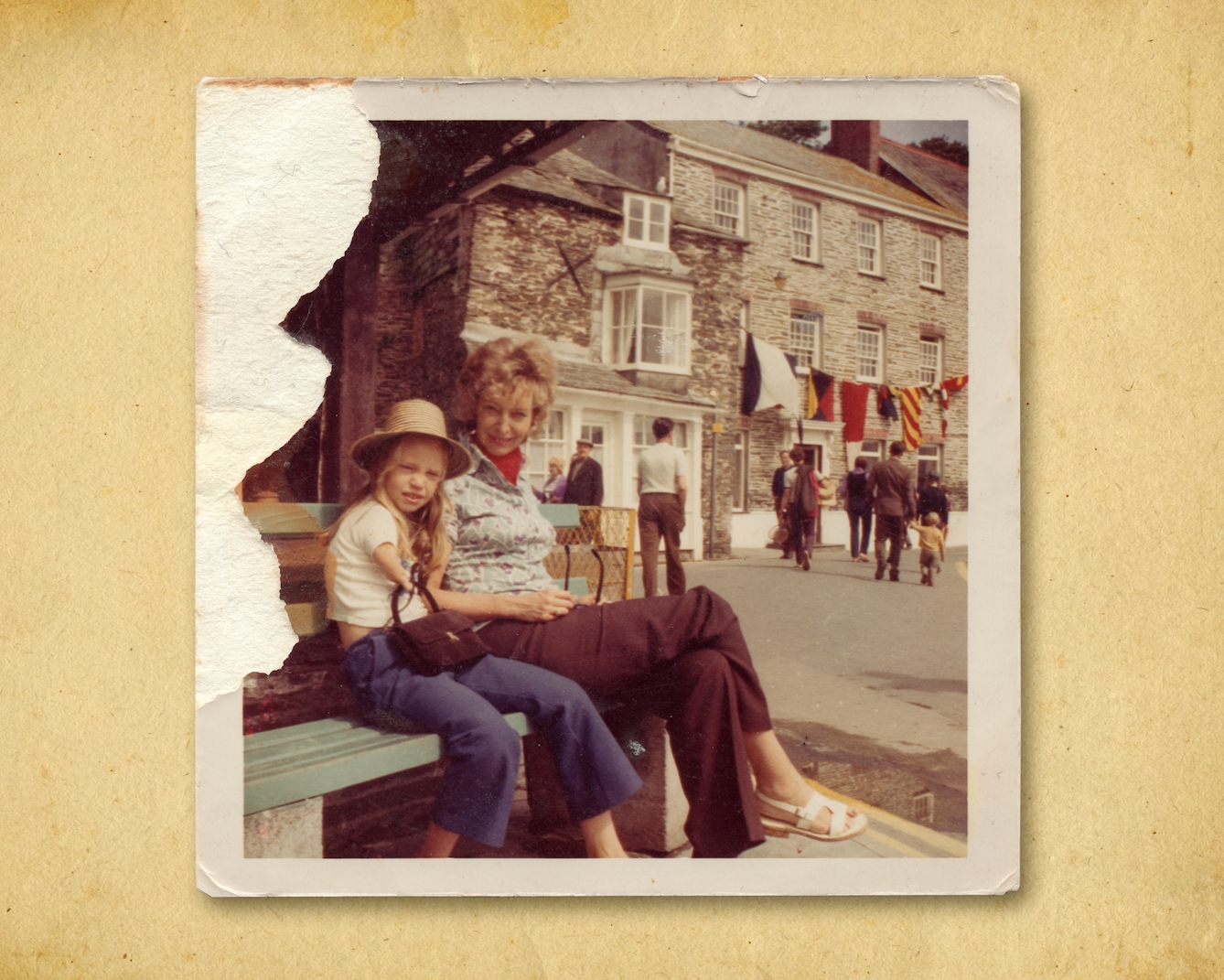

Alison’s mother was encouraged to give her up for adoption after she was born, but she chose to raise her at home, despite the challenges.

Disability was rarely discussed openly in the 1960s and like many disabled people at the time, thalidomiders were denied the same educational opportunities as everyone else – unless they fought for them. And once they left school, they often found themselves to be objects of curiosity, having to cope with prejudice and hostility for being different.

Care versus education

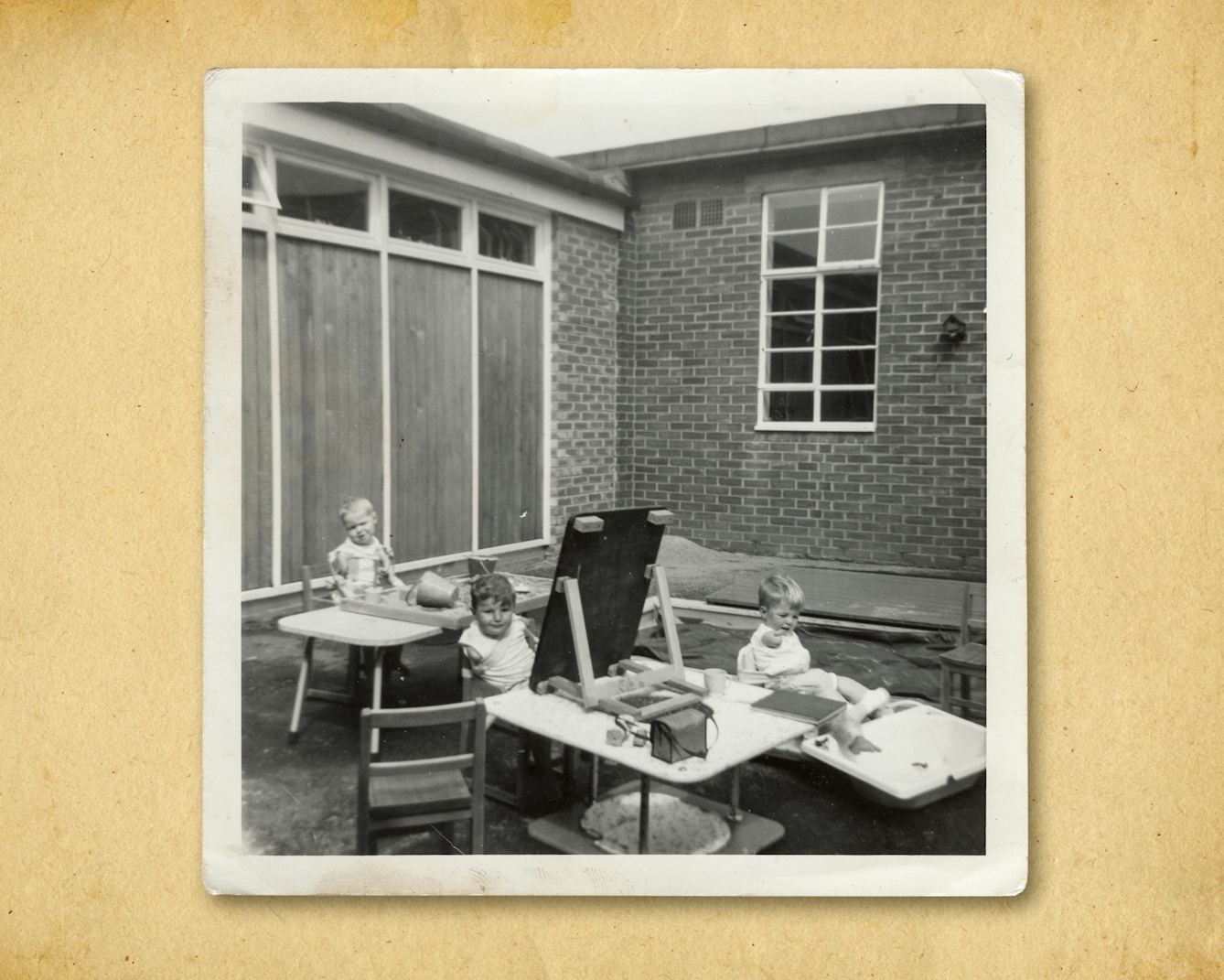

Many parents with thalidomide babies were encouraged by medical staff and social workers to put their child into institutional care rather than take them home to live. Grahame was a month old when he was sent to Chailey Heritage Craft School and Hospital in Sussex. He says: “For the first six or seven years it was all medically orientated. We lived outside a lot for the first five or six years, because [some] had TB, polio, other chest complaints, so if they were outside, we all had to be outside.”

Outside Chailey Heritage Craft School and Hospital, where children were encouraged to rest and play.

The emphasis of the school was on care rather than education and the belief that fresh air was hugely beneficial to children. At Chailey, where everybody was disabled, there were few expectations in terms of education. Like many ‘special schools’ at this time, education was limited and most of the children left having achieved fewer qualifications than their peers in mainstream education.

Children were taught how to look after themselves in terms of personal hygiene, and relied on each other. Grahame was part of “a group of thalidomide children within a larger group of disabled children; a close-knit circle”.

Former Chailey residents often felt that they were more independent than they might have been if they had lived in the family home and had more personal care. They were not, however, prepared for life in the outside world, where there was far more prejudice and judgement than in the relatively isolated community of the school.

‘Special schools’

Most children who lived at home were sent to a ‘special school’ in their area, which provided an education for children with a special educational need or disability. Like Chailey in the 1960s, the curriculum and educational expectations at these schools could be limited.

Kevin was denied access to the local primary school where his brothers and sisters had gone and instead went to Greenbank School of Rest and Recovery from the age of four to seven. He found that, “It was just a place to contain disabled people, and maybe give the parents a bit of a respite. But the education was… way down the bottom of the list of priorities.” He was educated “with kids from age four and a half to sixteen with all different disabilities and impairments in the same room”.

Class sizes were varied, but in most special schools there was no distinction between age and type of disability, so children with diverse needs might be taught alongside each other with no differentiation in the curriculum.

Kevin’s mother wrote to the local media complaining about the standard of education at his school and, fortunately for him, a forward-thinking headmistress, Pauline Skelly, read the article and was able to take him and ten other thalidomiders into her mainstream primary school.

Kevin.

Facing prejudice in an able-bodied world

Although many parents fought to get their child into a mainstream school in order to give them a better education, they were frequently denied a place, often without explanation. When a thalidomide child was accepted into a mainstream school, they might be the only disabled child in their year, or even the whole school.

Sarah describes how on her first day at secondary school she was asked in front of the school to choose which class she would prefer to be put in. She would much rather have been treated like everyone else.

With virtually no effort to raise awareness of disability at school, there were instances of bullying and name-calling. Survivors dealt with this in different ways. Simone used humour:

“I was ridiculed, I was teased. But I learned how to deal with that from a very early age and I did deal with it. I didn’t allow myself to be bullied, but not in a confrontational way… if children laughed at me, I laughed at them. If they said to me, ‘Oh, you walk funny – you walk like this.’ I’d go, ‘No, no, you’re doing it wrong. This is how I walk.’ And I’d put it on even more.”

And of course, ignorance and prejudice were not limited to the school playground. When Liz went to university, she recalls that a lecturer, “Informed me that the people… who I’d been at school with would have been psychologically damaged because they would have been… taught in the same set as me.”

Beyond the relative safety of schools and institutions, young people sometimes experienced horrendous incidences of harassment. For Annie, her lowest point was an assault on the street by a group of men in their twenties. The men attacked her simply for looking different; this was witnessed by other people who did not intervene or offer her assistance.

Annie.

Recognising capability before disability

Many battles lay ahead for thalidomide survivors as they entered the job market and faced preconceptions about their abilities, and general bigotry around disability and difference.

When Cathy was ready to work, she was assigned a disabled resettlement officer to help her find a job. But when the officer offered her basic manual work, her response was direct: “I have whatever GCSEs and CSEs... I’m sorry, I am not putting clips on the back of picture frames.”

Two days later the officer came back with something more suited to Cathy’s needs and abilities: a part-time job answering phones at a research institute. “I was there for nine years and I loved it, I loved it. I loved my work colleagues: I still see them and we still go out from time to time; I just loved it. It was me.”

At the same time as they were fighting everyday battles for the right to an education and gainful employment in a hostile world, thalidomide survivors and their families continued the fight to get justice and the fair compensation and care to which they were entitled.

About the contributors

Ruth Blue

Dr Ruth Blue is a freelance writer, researcher and oral historian with a PhD in fine art from the Slade School of Fine Art. She worked for Wellcome for 17 years, where she began working with thalidomide survivors in 2013, collecting their stories, photographs and artefacts. She has continued this work for the Thalidomide Society.

Hollie Chastain

Hollie Chastain is a mixed-media artist and award-winning illustrator living and working in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Coming from both a graphic-design and studio-art background, her work has a storytelling quality, mixing found material, strong graphic elements and modern palettes. Along with gallery work, she has illustrated work for Smithsonian Magazine, Warner Music and the Oxford American, among others, and authored and illustrated a book published in 2017. She currently works from a home studio with her husband Eric, two children, two cats and two dogs.