The 1990s saw a proliferation of virtual and robotic pets, inspiring either attentive care or neglectful guilt in their owners. Jenna Jovi describes how a demanding Tamagotchi launched her own particular digital devotion.

Adam Levene. That’s who started it. I’d like to say it began behind the bike shed, but Adam wasn’t that sort of kid, and if Adam wasn’t that sort of kid, then I was about as far from that sort of kid as it was possible to get. Case in point:

Start ’em young: me with original Game Boy, circa 1990.

But Adam was the first, and I remember the day he walked into Year 8, hands cupped protectively around the forbear of digital pets. There, in his palm, in all its egg-shaped and brightly-coloured plastic glory, lay a Tamagotchi.

By the end of the week I had one too, and, so it seemed, did the rest of the world.

If you’ve never heard of a Tamagotchi, because you were not yet alive in the 1990s, avoided children and/or general humanity back then, or just couldn’t give a flying Furby. Let me explain. A Tamagotchi was a handheld digital pet, the brainchild of Aki Maita and Yokoi Akihiro of Japanese toy company Bandai. They were unleashed in their native habitat in November 1996, and colonised the rest of the world in 1997. They proliferated quicker than anything conceived behind a bike shed because there had never been anything quite like it. They were every kid’s dream come true of their toy magically springing to life.

These wee digital beasties existed in real time and needed constant beep-beep-beep-beep-beep-beep attention: feeding, cleaning, playing, medicating. If you didn’t pay them that attention, they evolved into even more demanding adults. And if you kept on neglecting them, they’d die. Just let that sit for a moment: straight up digital death. As per the law of games, you could always play again, but each individual Tamagotchi’s life was finite.

For the original Japanese Tamagotchi, death was represented as an ominous ghoul-like creature hovering next to a gravestone, but for the first wave of US and European models, death was sanitised – naturally – to a sparkly three-eyed alien angel. In fact, the representation of ‘game over’ in the generations of Tamagotchi released since 1996 has its own fascinating history, but the one constant has always been death.

A Tamagotchi could also die from old age, but they only reached advanced years (real-time days) if you looked after them properly. No one in my school managed to do that, apart from, you guessed it: Adam Levene. Mine invariably evolved into neglected monstrosities with horribly shortened life spans. I got to experience both horrific grief and murderer’s guilt at the age of twelve: a deeply important life lesson for any pre-pubescent.

With due diligence to journalistic integrity, I don’t actually remember feeling much of a wrench when one of my aberrations expired, but I do remember when Adam’s first one copped it. He was inconsolable, weeping in the reading corner, shrugging us all away when we asked if everything was OK. Perhaps it was because Adam had put a little bit more time and effort into keeping his Tamagotchi alive, or maybe he was just a more sensitive and empathetic kid than the rest of us cold-hearted brutes. Adam wasn’t alone; there were tales of bereaved kids the world over.

This emotional attachment was given its own name, the ‘Tamagotchi effect’. The concept has since evolved to include any emotional entanglement we experience with machines, robots or software agents. While it ostensibly refers to digital beings, it’s worth remembering that we, as humans, can form emotional attachments to pretty much anything. I dropped a chocolate bar the other day and cried.

Cuddles and care

Perhaps the most powerful analogue object we may have experienced some sort of relationship drama with is the first ‘pet’ of our childhoods: the cuddly toy. As Alain de Botton (my favourite go-to-person for when something doesn’t quite compute emotionally) explains, soft toys are an important (and safe) projection of self for us when we’re growing up. Are digital pets just an extension of this? There’s one key difference: digital pets need us to look after them; they implore us to care.

The next digital pet after the Tamagotchi was another Bandai creation: Digimon (short for digital monster). In contrast to the unisex appeal of Tamagotchi, Digimon was explicitly marketed at boys. Why? Because you could connect with your friend’s Digimon and fight. And they were more… square. I had a Digimon, but I don’t remember playing with it much, probably because I was a girl and liked bevelled edges.

It didn’t take long for rival toy company, Tiger Electronics, to bring out the cheaper Tamagotchi competitor Gigapet, which I didn’t want because I already had a Tamagotchi and a square Digimon. By late 1997, Bandai had already released a second-generation Tamagotchi, with more things you could do, more things it could do, and just more general do-ness.

But my attention had already returned to an older digital pet, which I had been rearing on our family PC, long before my first Tamagotchi lived and died.

In 1995, San Francisco-based developer PF Magic released the PC game Petz (I questioned the ‘z’ back then, too). Petz – which came in the form of Dogz and Catz – were like Tamagotchi that lived on your home computer rather than in your pocket. You could adopt a puppy or kitten from a number of breeds, all with different personalities, which were in turn shaped by how you interacted with them. Simulating a degree of naturalism was key to the experience. Petz were designed to be “highly believable synthetic agents”, aided in large part by the blurring of reality and virtuality: Petz could strut across your desktop, leave their toys scattered across your Word document – even the mouse cursor was designed as a hand.

While Petz did age, progressing from infants to adolescents to adults, they then remained adults indefinitely. In making a digital pet as ‘real’ as possible, the developers had abandoned the only given in life: death.

The Tamagotchi effect notwithstanding, I remember the two reasons I became devoted to my Petz. Firstly you could make two Petz breed by spraying your selected duo with frankly toxic levels of love potion. Their progeny, through some algorithmic magic, would emerge as endless iterations of the combined feature sets of their parents. Infinite fun to a kid who was still a long way from the bike sheds. Secondly, Dogz 3 came out at the same time as dial-up internet arrived, giving me my first contact with online communities. Hello fandom. A huge online subculture grew up around the game, and I soon learned it was possible to modify (or ‘hex’) my Petz to have anything from blue spots to bat wings to arthropod antennae.

Both these reasons gave me a real sense of ownership and connection to my Petz through customisation. Realism didn’t matter; this was about making something my own and bringing it to life; what kid is going to say no to playing God?

Imagez of hexed Dogz and Catz.

After the success of Petz, PF Magic went on to release Hamsterz, Horsez (even they regretted the ‘z’ at this point), and the super-creepy Babiez, which I never played because the disk was corrupted. To be honest, I’m glad, because babies and breeding is a virtual red line for me. But Petz was the progenitor of a strong line of PC-based digital pets and simulations. Other notables of this pedigree are the cult classic Creatures, and the Big Daddy of them all, The Sims, which also later spawned its own imaginatively titled pet-based expansion pack (brace yourself), The Sims: Pets.

It took Japanese console wizards Nintendo to push the evolution of screen-based digital pets forward via some crossbreeding with their hand-held littermates. The result was the ultra-cute Nintendogs, which launched with Nintendo’s handheld DS in 2005. Nintendogs was an instant hit with a new generation of kids to whom Tamagotchi were either a new Pokémon or a strand of avian flu. Advances in computer graphics pushed realism further than in any previous digital pet game. There were also new interactive experiences: these sweet little eternal-puppies could respond to and learn voice commands, while you scratched their bellies with your stylus – if you still had one.

On booting up my copy of Nintendogs: Chihuahua & Friends (for research purposes of course), I discovered I’d called my pup Randolph. I think this may have been my ‘Citizen Kane’ phase; I was 21 in 2005, and still buying (digital pet) games; the bike shed had become the student bar, and I wasn’t exactly a regular. Nintendogs didn’t grip me in the way earlier digital pet games had, possibly because I was not about to shout, “RANDOLPH, SIT!” on the bus to a lecture.

But at this point even I can admit to no longer being the target audience. Nintendogs resonated with a new generation by bringing the portability of Tamagotchi together with the processing power and complexity of earlier screen-based iterations. Digital pets were here to stay. “I SAID STAY, RANDOLPH!”

Like the Petz series, Nintendogs was more of a simulation than a game in the traditional sense. While it made use of the DS’s internal clock to track the passage of time, the realism stakes were set pretty low.

If you neglected Randolph for a few days, you wouldn’t return to find he had committed suicide next to his snow globe, but merely run away off-screen. A tap of the stylus would be enough to bring him gambolling back, bearing a gift in the hope that you’d start treating him better. This sent out the message to kids everywhere that abuse is totally forgivable, and comes with bonus presents for the abuser.

The cybernetic tortoise

The original digital pets came from somewhere much more sentimental. The story goes that Aki Maita came up with the idea for Tamagotchi while watching a TV commercial in which a boy is forbidden from taking his pet turtle to school. She wondered whether she could create a digital pet for him to take along instead.

With this in mind, when I asked Andrew Nahum, Keeper Emeritus at the Science Museum (who contributed to the Science Museum’s 2017 book ‘Robots’, and also writes on cybernetics), his thoughts on the possible origins of digital pets, his answer made me smile: “Grey Walter’s tortoises.”

William Grey Walter was a British neurophysiologist who in 1948, as a pet (ba-dum tss!) project, began building what are widely considered to be the first ‘scientifically significant robots’. Grey Walter’s ‘tortoises’ (as he called them) were autonomous robots that used two inbuilt sensors to navigate their environment in an attempt to model the brain.

As Andrew explains, “They pioneered lots of the features of later digital pets – sensitivity to touch and light, and quite crude circuitry and algorithms producing surprisingly lifelike behaviour. So I guess they can be thought of as the prototypes for later digital and robotic pets.”

The model of the tortoise may not be mere coincidence. Grey Walter set out to make what he called a model animal, a ‘sim’ in all but name. He called (and therefore gendered) his two earliest models Elmer and Elsie, building kennels for them to charge up in, which only added to the sense of them being a kind of pet.

Grey Walter himself shamelessly anthropomorphised these devices. “She is taking her bottle,” he told a visitor, when Elsie entered the kennel to recharge. Andrew adds, “I don’t think Grey Walter would have minded them being called pets, but his intention was more serious.”

Cybernetic tortoise, c.1950. Invented by William Grey Walter.

Staring at Elsie now in her glass box in the Science Museum, it seems surprising that people in 1949 who saw her deftly navigating obstacles thought that she really was sentient; even Grey Walter believed his tortoises demonstrated self-awareness. “I guess our expectations go up all the time,” Andrew muses.

But perhaps the emotional response Elsie elicited in her owner and the general public alike is the real link between her and her digital descendants: the ‘Elsie effect’. I’m left wondering if a kid today playing with a Tamagotchi would find it less beguiling knowing there are ‘better’ versions out there?

In parallel to the explosion of hand-held and screen-based digital pets in the mid-1990s came a new era of their robotic cousins (and Elsie’s direct descendants). Top of every kid’s Christmas list in 1998? The ubiquitous and rather creepy bug-eyed bird monstrosity otherwise known as a Furby.

Furbies could move their eyes, mouths and ears, as well as jiggle around a bit, but the real reason you wanted one was because they could learn to talk. Initially they spoke ‘Furbish’, but the longer you spent with them, the more English they learned. Not only that, they could chat to other Furbies too. I remember mine spontaneously chattering away to itself in in the middle of the night, then triggering my brother’s one in the adjoining room, and it all ending up a bit ‘Rosemary’s Baby’.

Furby transpired to be a black box of overhyped mystery, but that was part of the allure: I was convinced there was more going on than met the eye. Instead of there being disappointment in the gap left between expectation and reality, Furby managed to create even more expectation; their PR team must have been laughing at our collective gullibility, possibly via the secret camera mounted inside each Furby.

My most memorable experience of robotic pets of this era was Aibo, Sony’s iconic robot dog. Aibo was a serious robot pet, with an even more serious price tag, which meant that it wasn’t just for kids. My dad made business trips to China, so we were lucky enough to find an Aibo under our Christmas tree in 1999.

They say ‘a dog isn’t just for Christmas’ but our Aibo was just that: it came out of its box exactly three times before being deemed too much of a pain to get going. It has been sitting in my mum’s basement ever since.

Pet cemetery

This brings us back to death. In 2006, after producing numerous generations of Aibo, Sony ended production. And in 2014, they stopped customer support altogether, including maintenance. Some devoted owners, experiencing the Tamagotchi effect turned up to 11, will now go to any lengths to keep their beloved pets alive. A lucrative second-hand parts market has emerged, and I am now seeing my mum’s basement in a very different light.

Digital pets themselves have undergone something of a virtual (no pun intended) sanitisation since the days of Tamagotchi. Death, at least as part of the simulated or game experience, has all but disappeared. Nintendogs never age, staying as puppies indefinitely, and in the 2011 Xbox One Kinnect game, Kinnectimals, the pets remain cubs forever. Overly cute – or ‘kawaii’ – character design seems to dominate every app-based digital pet game currently on the market. Even the mega-successful ‘retro’ virtual pet app Hatchi cannot die.

Updating the digital pet genre

Returning to a life-cycle with death as the endgame, I can now bring my personal history of digital pets up to date. I am developing a game with Ellie Silkstone of indie games studio Xylophone Games in response to the 2017 Wellcome Collection exhibition ‘Making Nature’. Our game, P.E.T., updates the digital pet genre, and was partly inspired by the curious story of the Facebook game Pet Society.

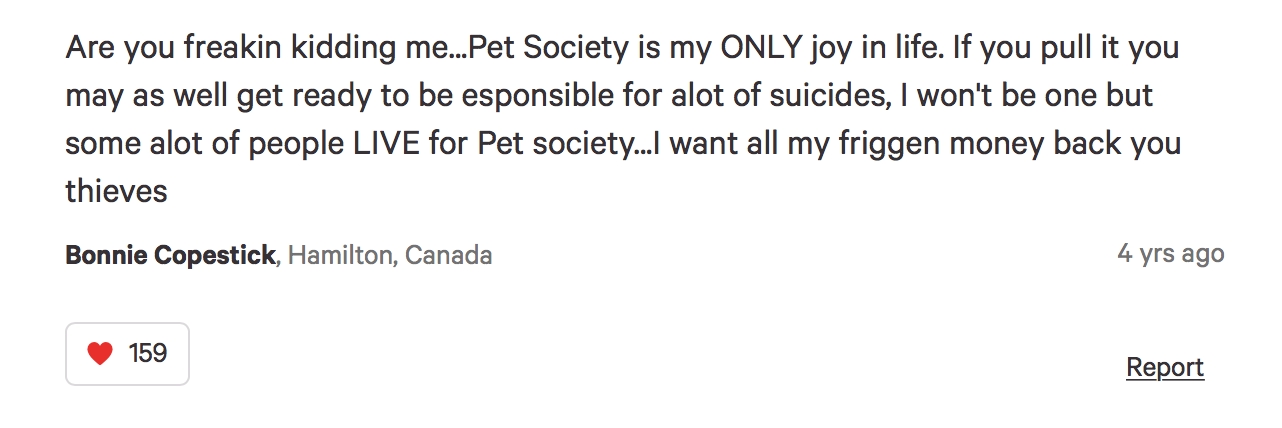

Launched in 2008, Pet Society was one of the most popular Facebook games of its time, with hundreds of thousands of users across the globe. Players could name, create and look after pets, and share them with other users. But by 2013, the game’s owners, EA, decided that with profits falling, it was time to pull the plug.

While death for an Aibo was a physical thing (ie breaking) here was the definite and sudden end of something totally digital. Pet Society owners the world over were left grieving but also furious: they mobilised and lobbied EA to release the data and return their beloved pets. To this day, they still haven’t got them back, and as of writing, the (very polite) Facebook group ‘Please Save Pet Society’ still has nearly 11,000 owners pining for their lost pets. Digital death has come full circle; not part of the game, but as an unforeseen consequence of a commercial imperative.

A ‘reason’ comment left on the Change.org ‘Save Pet Society From Closure’ petition page.

And to bring things even more up to date, the Ozimals brand of ‘breedable’ rabbits in the sim of all sims Second Life was hit with a cease and desist order. The databases, which allowed the bunnies to eat – and Ozimals to keep on profiting – would cease to function as of 17 May 2017. The result? All bunnies in-game would starve to death, or as the owner of Ozimals so gently put it, ‘hibernate’.

Ellie and I found this tension between real and digital death fascinating. And so P.E.T. was born, a simulation exploring the digital life – and death – of a virtual pet. In steering that pet through its life cycle, the game explores the ethical implications around the customisation and commodification of pets, alongside the player’s shifting relationship to something that makes no (digital) bones about the fact it isn’t real.

When I talked about P.E.T. to the philosopher and social epistemologist, Professor Steve Fuller of Warwick University, he was very interested in how the game could bridge the gap between our understanding of the rights of animals and the rights of robots. But the bigger question P.E.T. asks is not just about our responsibility to our digital companion animals, but about the very real ethical responsibility that the company that creates them has for us.

In Japan, plummeting birth rates are being linked to the popularity of digital ‘pet’ girlfriends with young men.

As part of my research for P.E.T., I exhumed my old Tamagotchi. With a new battery installed, its digital resurrection was complete. Within minutes my egg hatched, and a little black blob of embryonic pixels was bouncing around the screen. I quickly fell under its spell, responding to its every beep-beep-beep-beep-beep-beep need. A day later, it evolved into a larger white blob of pixels, and two days after that, into a rather ugly head with a beak, and I still diligently attended to its every need, even as my patience wore thin, particularly with the ‘guess which way I’m going to turn’ game.

During a day of meetings and beep-beep-beep-beep, I quickly realised I had to mute my pet. Without audible reminders, my Tama had a patchy day of care, and when its next evolution took place, it became one of the ‘disobedient’ characters, a sort of duck head with legs. Fair enough, I thought. The next day was even worse, and when I got home, after I had emailed, cooked, washed up, got angry at someone on Twitter and ‘Question Time’ simultaneously, and was about to fall asleep, I suddenly remembered I’d not checked my Tamagotchi all day. All day. It was midnight and this is what I found:

I can barely look: my neglected Tama.

That is a sleeping Tamagotchi surrounded by no less than four of its own excretions; it may have done more off screen for all I know. After a Tamagotchi falls asleep, you have to wait for it to wake up to clean it up. It wouldn’t wake up for another ten hours.

I wasn’t expecting it, but as I looked down at this pitiful creature in my hand, I suddenly felt a pang of guilt. I’d done that.

The next day was even busier, and I forgot about my Tamagotchi once again.

When I next remembered to check, I found the sparkly three-eyed alien angel had been.

My Tamagotchi was dead.

I felt destroyed.

About the author

Jenna Jovi

Jenna is a screenwriter working across TV, film, games and VR. She can mostly be found writing at her computer, except when she’s at her other computer(s) playing video games. P.E.T., which Jenna is developing with Xylophone Games and Wellcome, is due to be released later this year.