Weeks of worry, pain and confusing input from an array of health professionals accompanied Joanna Wolfarth’s struggle to breastfeed her baby. She gradually discovered evidence going back millennia that indicated her problems were not new ones.

My son is four weeks old and I think I’ve failed him.

Wait. My son was just one hour old when I failed him – I forgot about the tiny bottle of formula the midwives insisted I fed him. He cried and wouldn’t take it. We were in the recovery ward after a long labour, a cannula stuck at an awkward angle on my hand, my arms covered in bruised track marks, my body numb as they rushed me to get him to latch. I struggled to hold him. Leave us alone. Leave me alone.

The next day, flying high, my new family of three made the journey to the end of the postnatal ward, where the breastfeeding counsellor was giving a talk. She spent the first 15 minutes telling us how terrible formula is. I had the postpartum sweats and my baby seemed to be feeding well. I remembered that sip of formula. Was my baby corrupted now?

(I didn’t know then that formula is so called because in the 19th century scientists tried to come up with a safer substitute for the unpasteurised animal milk people had been attempting to use as an alternative to breast milk. Formula might not be as perfectly designed as breast milk, but it has a sometimes life-saving history.)

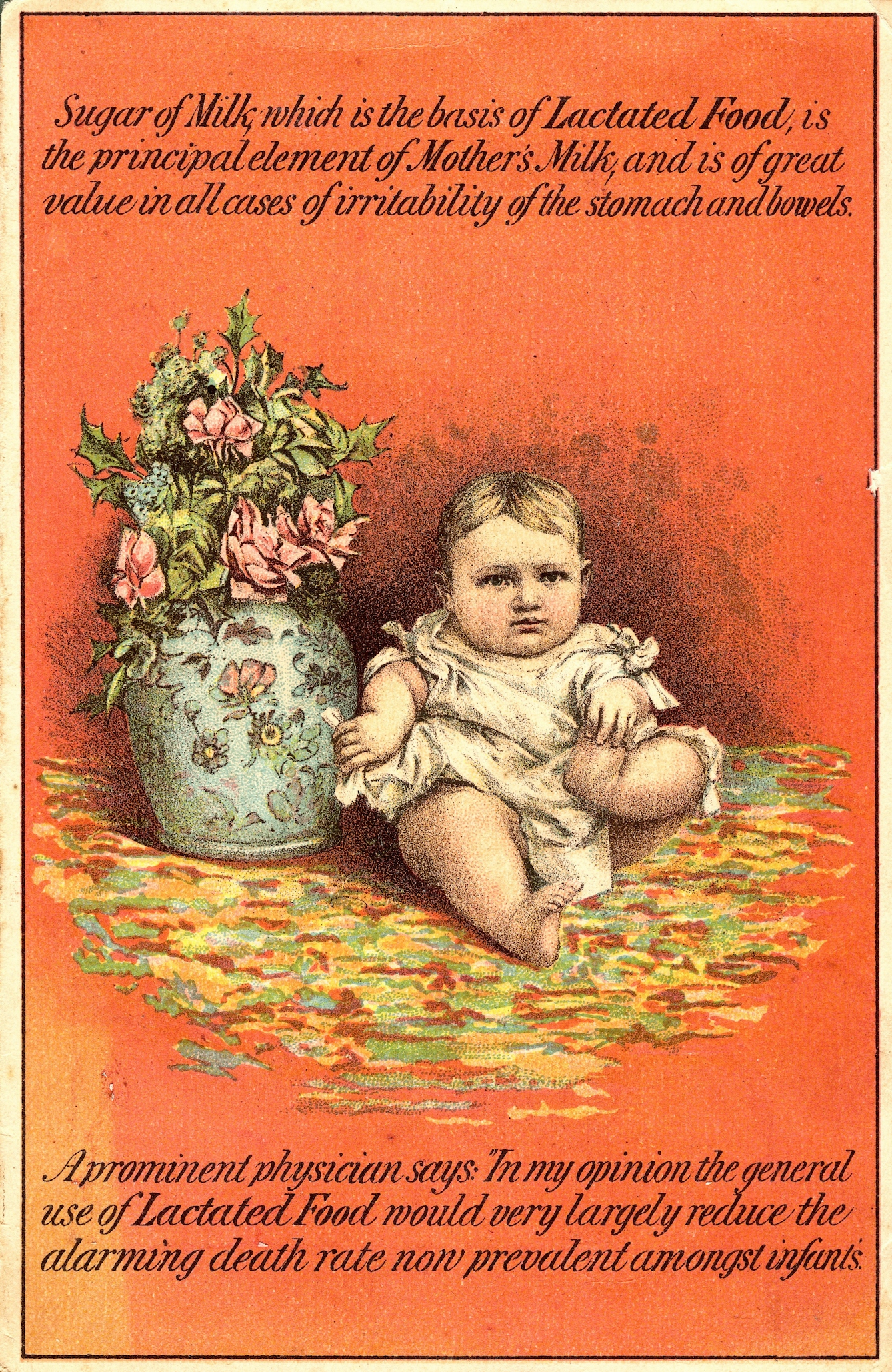

Lactated Food, made by Wells, Richardson and Co., advertised a formula that, like many coming on to the market in the 19th century, was based on milk powder, flour, sugar and salt. It was, however, safer than unpasteurised fresh cow's milk.

The midwives tried to help me harvest colostrum with a tiny syringe. But I didn’t want anyone to touch me any more. Leave me alone with my baby. Let my sore body heal. They said my latch looked good. They said I nursed him like a pro. He fell asleep on my chest, milk-drunk, and we laughed and took photos. According to the Ancient Greeks, breast milk formed the Milky Way and gave Heracles his supernatural powers. My body is making magic.

A surprising taboo

I’m eight months pregnant and a midwife is holding a small plastic doll to a perfectly spherical knitted boob. Nose to nipple. Simple. A woman raises her hand and asks about expressing milk, so maybe her husband can do an occasional feed.

“We aren’t allowed to talk about formula or bottle feeding at all, as we are a breastfeeding-friendly hospital.”

Nobody mentions mixed feeding, when nursing is combined with bottles of expressed milk or formula. Or what to do if bottle feeding is a necessity. Or that it’s OK to not want to feed from your body.

(No one tells me that archaeologists have found breast-shaped clay bottles dating from 2000 BCE that contain traces of human and animal milk, and therefore attempts at mixed feeding predate Christ. Some of these were found in infant graves, so maybe these attempts were not successful. Still, bottles are found throughout history and I would have liked to have known that not all women found breastfeeding easy.)

A 17th-century baby's bottle. Problems with breastfeeding have a long history.

Something is wrong

My son is three weeks old and I know something is wrong, but I’m told newborns can be skinny. At the breastfeeding support café I’m told he’s feeding well. I nurse in public and feel like a mum. It still hurts and I know it's not supposed to. He cries all the time. The GP doesn’t weigh him but tells me all is fine.

Health visitors suggest different feeding positions. I can’t wrangle him into the football hold. I don’t have the pendulous, milky bosoms like on the videos. Try more pillows. My endlessly supportive partner constructs a fortress of cushions around us and I sob from within this prison. I’m hot and don’t want anything else to touch me. Am I doing it all wrong? How did babies feed before cushions?

(During antenatal classes we were told all newborns could climb up to the nipple and latch on perfectly before the umbilical cord was cut. But not all newborns can do this, just as not all mothers find breastfeeding straightforward. Wet nursing has a complex history, but women feeding babies other than their own originated out of need long before wet nursing was associated with choice and status.)

A print from 1780 showing a wet nurse returning a baby to its natural mother.

I’m desperate but don’t want to stop. At the breastfeeding café I’m told we are so used to seeing bottle-fed babies we don’t know how to hold breastfeeding infants any more. But I cradled my dolls to my flat chest. I watched my mum do night feeds and my cousin nurse when she was eight hours old. But this goes deeper than childhood memories – this is pure instinct; those precious moments when it still feels as if we are one.

(And I’m lucky that I have the time for us to be one. During the Industrial Revolution, as women started to work outside the home, babies were no longer able to feed on demand. This probably affected the mother’s milk supply. At least I have good, paid maternity leave.)

Back to hospital

My son is 28 days old and the midwife is here for our final visit and weighs my son with the old-fashioned scales that I later learn are notoriously inaccurate. But we don’t need scales. I can see with my eyes and feel with my heart that he has lost too much weight. We are told to go to A&E and he is admitted.

I am distraught and guilty. And have a glimmer of resentment that I am in hospital and not at home curled up in bed. When did I last have a dreamless sleep?

My son is four weeks old and I am reading the ingredients on a tiny bottle of pre-prepared formula. But it is too late, he’s drunk it, and with the fish extract and soy I feel I have failed. I dutifully feed my son from both breasts, then give him a bottle and connect myself to an industrial pump to try to extract the next top-up from my exhausted body. We are strictly instructed to do this every three hours.

And I love the NHS, but everything feels so inconsistent. This regime seems impossible and they are discharging us to certain formula feeding. Finally the lactation consultant we requested arrives. She does not watch us nurse. She looks at my son and tells us she is used to working with newborns and so can’t help my four-week-old. She tells us to see someone privately. This hospital has a tongue-tie clinic. No one mentions it.

(Ancient medical sources refer to cutting the membrane that connects the tongue to the floor of the mouth if it is too thick and restrictive. In the Middle Ages, midwives would snip the baby’s membrane with a sharp fingernail. Nowadays there is conflicting information and advice as to whether tongue-tie effects feeding. Does this signify a loss of knowledge in a more medicalised world? Or is it an unnecessary intervention? How am I to know?)

An illustration from a much-reprinted 17th-century manual on midwifery, written by a 'Pseudo-Aristotle', an author claiming to be Aristotle, who was still revered as an expert in the sciences many centuries after his death.

For the next week I feed, top up, express, sterilise, cry, every three hours. No one has told us when to stop this regime. At the hospital they walk me through sterilising bottles, as nothing has prepared us for this. No one said this is mixed feeding and happens all the time. We are passed, uselessly, from health visitor to GP to peer supporter.

Still it hurts, and now there is thrush and I can’t even tell you the problems we had treating that. But I can tell you about the weeks of deep, lingering pain. The agony. Of biting down on my knuckles and the fear of the next feed. Don’t tense up, otherwise the milk won’t let down.

My son is five weeks old and maybe I failed him again.

A controversial cut

The private lactation consultant is in our home and her no-nonsense manner is reassuring. She snips our son’s tongue tie on our sofa in the dark evening. There is a ritual air, emotions heightened by exhaustion, desperation and vulnerability. The tension is cut and there is calm. A pain-free feed. Relief.

Yet on we struggle. Another private lactation consultant. Weepy calls to the fantastic breastfeeding-support phone line, scrutiny of websites, including Mumsnet, where a chorus of women give armfuls of advice and encouragement and their words still make me cry. I get vasospasm, where my blood vessels tighten and go into spasm and I feel sharp pain in my nipple. This is a new agony, and my GP incredulously tells me she has never heard of that happening. I’m ashamed that my body and my baby are still apparently doing it wrong. But I do not give up and neither does my determined little boy.

(I later find nipple shields made from wood, silver, ivory and glass in the Wellcome archives, which suggest that women have long tried to manage nipple pain. This makes me feel less alone.)

Nipple shields made from glass, ivory and silver.

Then, suddenly it is not so hard. It hurts less and less. He’s learned to thump my breast when he wants the milk to come faster. Rolls of fat appear on his arms and thighs. His chubby hands explore my face as he feeds. We keep going and going and suddenly it is easy and I relax about my supply and the odd bottle feed. My boy is happy and smart and strong. So why do I still feel guilty and raw at 3am when everyone else is asleep, even as the feeling of failure mutates into a small ball of sadness that somewhere along the line we were let down?

Soon those chubby hands are squelching chunks of banana and reaching for twirls of pasta. My boy greets every new food with enthusiasm and the weight I’ve been carrying starts to diminish. He drinks water from a small, orange cup and has eaten handfuls of sand in the park on at least one occasion. I ignore the raised eyebrows and keep on breastfeeding my toddler son. Memories of the confusion, guilt and pain fade into a fog.

Now, as I fish a tiny piece of broccoli from behind his ear as I feed him to sleep, it feels like a dance we learned together.

About the contributors

Joanna Wolfarth

Dr Joanna Wolfarth is an art historian and writer. Formerly Visiting Lecturer in Southeast Asian Arts at SOAS, University of London, she now teaches Global Art History at the Open University, UK. A specialist in the cultural history of Cambodia, she writes widely on art, gender and cultural histories. Her first book, ‘MILK’, on the messy poetics and politics of breast milk and motherhood, is out now.

Rosie Barnes

Rosie is an award-winning London-based documentary photographer. She started the project ‘No You’re Not – a portrait of autistic women’ in 2018 and the work now extends to around 35 participants. Rosie’s initial interest in the subject came from autism within her own family, but during the making of the work, she has discovered her own neurodivergence. Rosie is also founder of Satsuma Neighbour, which is a radical vision to revolutionise housing for those with low support needs in a truly inclusive way.