Today cocaine use presents a series of major problems for governments to tackle. But in the 19th century it was fervently hailed as the perfect solution to a very specific issue – safe anaesthesia during surgery.

In the modern popular consciousness, cocaine is usually defined by images of extravagance, violence and addiction. The spectacular wealth and self-annihilation of Tony Montana in the 1983 film ‘Scarface’, the National Crime Agency’s ‘Every Line Counts’ campaign, and Sadiq Khan’s condemnation of gang violence fuelled by “middle-class cocaine parties” all depict cocaine as simultaneously indulgent and destructive – the vice of the affluent.

In the late 19th century, though, cocaine had a very different set of associations, which are largely forgotten about today. Before the harmful consequences of cocaine addiction were fully understood, cocaine was celebrated as a revolutionary medical technology: the first effective local anaesthetic.

In 1884 a young Viennese ophthalmologist named Karl Koller discovered that a mild solution of cocaine would, if introduced into the eye, deaden the nerves’ sensitivity to pain. News of the discovery spread rapidly through Europe and America, provoking ecstatic reactions from medical professionals and the public alike. In the first six months of 1885, over 60 articles on cocaine appeared in the pages of the British Medical Journal.

Christ is the patron of infirmaries, hospitals and homes, and cocaine is one of the blessed instruments of his pain-removing mission.

Henry Power of the British Medical Association wrote that “in the discovery of cocaine, a new era seems to have dawned”. The doctor and journalist Alfred J H Crespi described cocaine as “a discovery to captivate the imagination of mankind”. For the Scotsman newspaper, the new drug seemed to be an (almost literal) godsend: “Christ,” it wrote, “is the patron of infirmaries, hospitals and homes, and cocaine is one of the blessed instruments of his pain-removing mission.”

Chloroform and the risk of eternal sleep

It’s hard for us now to grasp why cocaine anaesthesia provoked this type of rapturous (even religious) response. We live, after all, in a world where surgical pain relief is taken as a given, but late-19th-century options for anaesthesia were considerably more limited and problematic.

General anaesthetics like chloroform and ether had been used successfully for almost 40 years by the time cocaine entered the public consciousness, but these methods came with several problems – not the least of which was the worry that those who went under chloroform might never wake up. The danger of anaesthetic death was a consistent presence in the minds of surgeons and patients alike.

In 1894 Dr J McNamara penned a somewhat melodramatic letter on the subject to the British Medical Journal. “The records of death by chloroform,” he wrote, “are monstrous in their frequency. Is it not time to discard the lethal chloroform, and thus put an end to the human sacrifice that is weekly offered on [its] altar?”

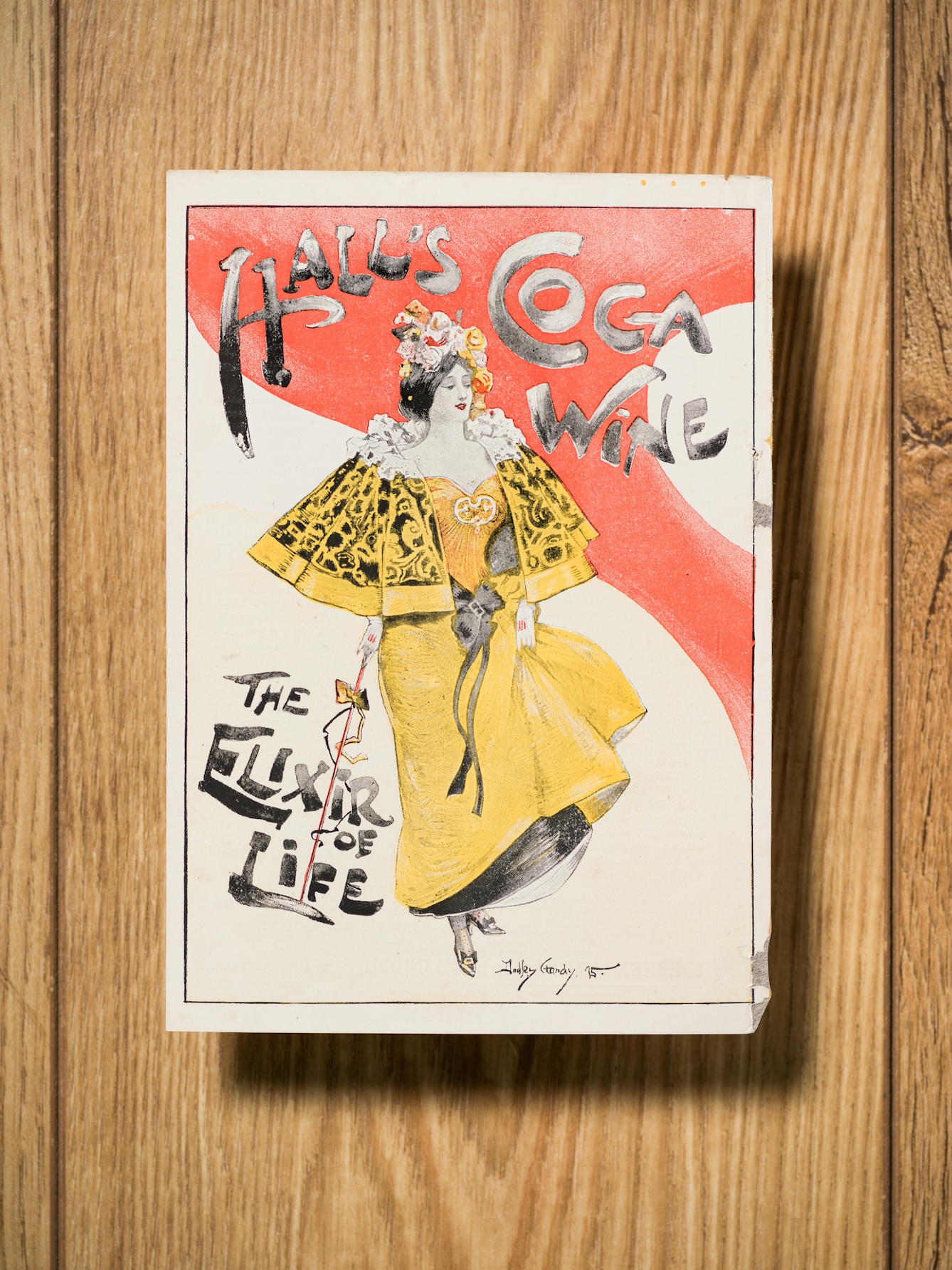

With descriptions ranging from “gift from God” to “elixir of life”, the Victorians were effusive in their praise of the wonders of cocaine.

If doctors were cautious of general anaesthesia, then patients were often even more so. One GP from the small Scottish town of Garlieston declared that: “There are many people who dread chloroform so much, that they decline to take it, unless practically coerced into doing so.”

Koller’s discovery offered a solution to the 19th century’s pain problem. Cocaine could easily eliminate pain by being rubbed onto a part of the body or being injected via hypodermic, and do so without the fearful prospects of unconsciousness and death. In this context it is easier to see why, at the time, cocaine looked like such a technological marvel.

In July 1884, only months before Koller’s discovery was announced to the world, the Provincial Medical Journal counselled its readers that: “Scientific medicine, if it means anything at all, must aim at the relief of pain. And with the attitude of the public expecting relief, our duty is clear – to afford it.” As the 1800s drew to a close, it seemed like medical science had finally achieved this aim. A correspondent writing to Chambers’s Journal called the drug “a wonder of the age” and W H Dallinger, writing to the Wesleyan-Methodist Magazine described it as the “Ultima Thule of anaesthetics” – a reference to a fantastical island in Greek mythology that lay beyond the frontiers of the known world.

It appeared that doctors now possessed a tool that might take them beyond the furthest frontiers of their own discipline, allowing them to effectively banish pain and perform the most taxing of surgeries with ease.

The ‘ideal’ anaesthetic

Many in the medical profession regarded cocaine as proof of what modern therapeutics could achieve with the aid of cutting-edge science. But the drug also intruded into the lives of everyday people in a variety of surprisingly intimate ways.

One of the most popular fictional characters of the era was also one of its most famous cocaine users. The opening scene of Arthur Conan Doyle’s second Sherlock Holmes novel, ‘The Sign of Four’ (1890), shows the great detective unpacking his “hypodermic syringe” from its “neat morocco [leather] case” and injecting himself with a 7 per cent solution of cocaine.

Holmes had been enthusiastically received by Victorian readers from the first, with early reviews comparing the detective to some of the most influential figures of the age – the Scotsman newspaper called him “a scientific genius, a Darwin of detectives”. It might seem strange to us now that Holmes and his cocaine habit were so unproblematically received by Victorian audiences, but this makes more sense in the context of cocaine’s contemporary standing as an innovative, modern ‘wonder drug’.

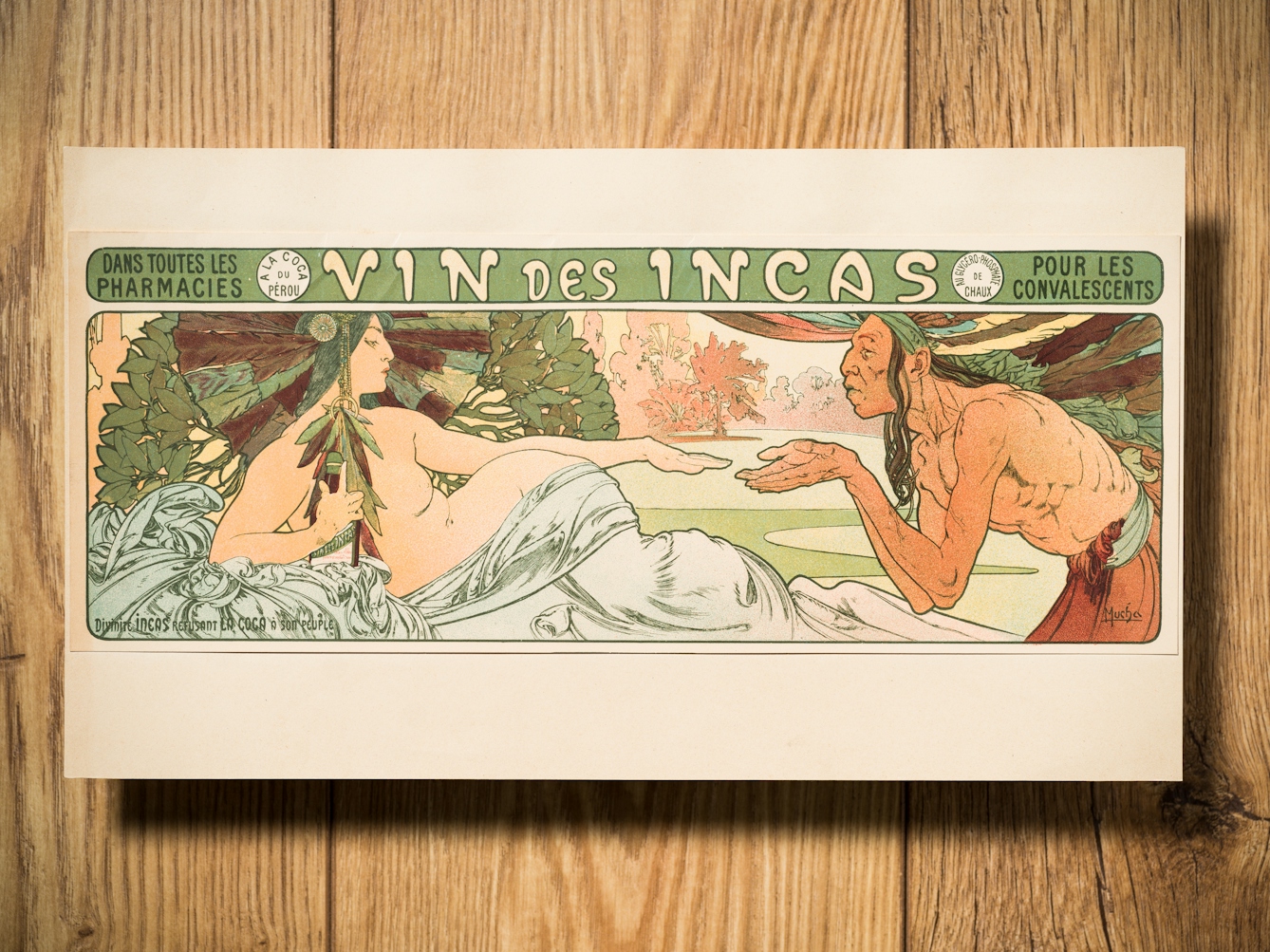

Advertisements produced in Europe for cocaine-based products often reflected colonialist attitudes towards native American peoples, on whose land the coca plant could be found.

Arthur Conan Doyle was trained as a medical doctor himself, and cocaine represented the newest triumph of medical technology. Having Holmes use cocaine (rather than some other drug, such as morphine or opium) was a useful shorthand to suggest the rapidity and technological precision of the detective’s mind.

Victorian reviewers reacted enthusiastically to this idea. Newspapers the Graphic and the Morning Post observed that: “Mr Holmes shows forth all the gifts of his calling in high perfection. He never sleeps when he has a case on hand. His knowledge is encyclopaedic” and “he must be either engaged in unravelling a first-class mystery, or in consoling himself for the want of one with cocaine”. Cocaine, the medical wonder drug, seemed an ideal fit for the criminological superman.

Outside of fiction, the drug was also a daily presence for many people. For decades cocaine was the standard remedy for seasickness, hay fever, and for the congestion brought on by colds and flu. The Burroughs Wellcome Company manufactured a handy ‘cocaine spray’ cold remedy, small enough “to be carried in a waistcoat pocket”.

Cocaine anaesthesia was also used for cosmetic surgery: Dr John O Roe of New York promised to painlessly resculpt his patients’ noses into the fashionable aquiline shape of the day. The Victorian celebrity tattooist Sutherland Macdonald frequently injected his clients with the drug before he began work, so that he could create even the most elaborate ‘statement piece’ tattoos without pain. Cocaine was so influential in enabling pioneering forms of rhinoplasty, cheiloplasty and skin grafts that the Hampshire Telegraph speculated that Victorian society might be on the edge of a new aesthetic age, where “a new countenance may be as easily ordered as a new bonnet”.

In looking back at the ‘revolutionary’ potential of cocaine for the Victorians, we are confronted with just how much our perceptions of medicines – and of medical technologies – can change over time. For us now, cocaine symbolises the dangers of crime and addiction, but for its earliest users, cocaine offered the tantalising promise of a modern age of medicine – an age without pain, of effortless surgery, and the easy modification of the human body.

About the contributors

Douglas Small

Dr Douglas R J Small is a Wellcome Trust research fellow at the University of Glasgow, where he researches the history of drugs and medicine in Victorian literature and culture.

Benjamin Gilbert

Ben is a senior photographer for Wellcome. He is happiest when telling stories with his photographs, whether that be the health implications of rural-to-urban migration in India, or the dedication of the workers who power the NHS.