Hooked up and seated in the chemotherapy chair while undergoing treatment for bowel cancer for hours every fortnight, artist Clare Smith created about 70 abstract drawings. She started the drawings out of boredom, as a way to fill blocks of dead time. Although the bowel cancer is now in remission, during treatment it became clear that she also had late-stage breast cancer, for which she is still being treated. Her art is a testament to the power of creativity to bring respite in a crisis.

Like many people, I found the symptoms frightening and hoped they weren’t what I thought they were, but they were. In 2018 I was diagnosed with rectal cancer that had already spread. The surgeon suspected a connection with my breast cancer in 2010 but then said there was no connection. Turns out he was both right and wrong.

The period between the diagnosis, seeing the oncologist, and starting treatment felt very long and was beset by delay. When I did see the oncologist, I remember her saying she wanted to order some extra tests and “if there is a delay, it’ll be my fault”.

Of course, there was a delay: either the results weren’t in or she hadn’t seen them. My husband Roger and I both felt angry and frustrated, especially as the appointment for starting treatment was cancelled while we were having dinner the night before; a few days probably makes no difference, but at the time it always feels like it will.

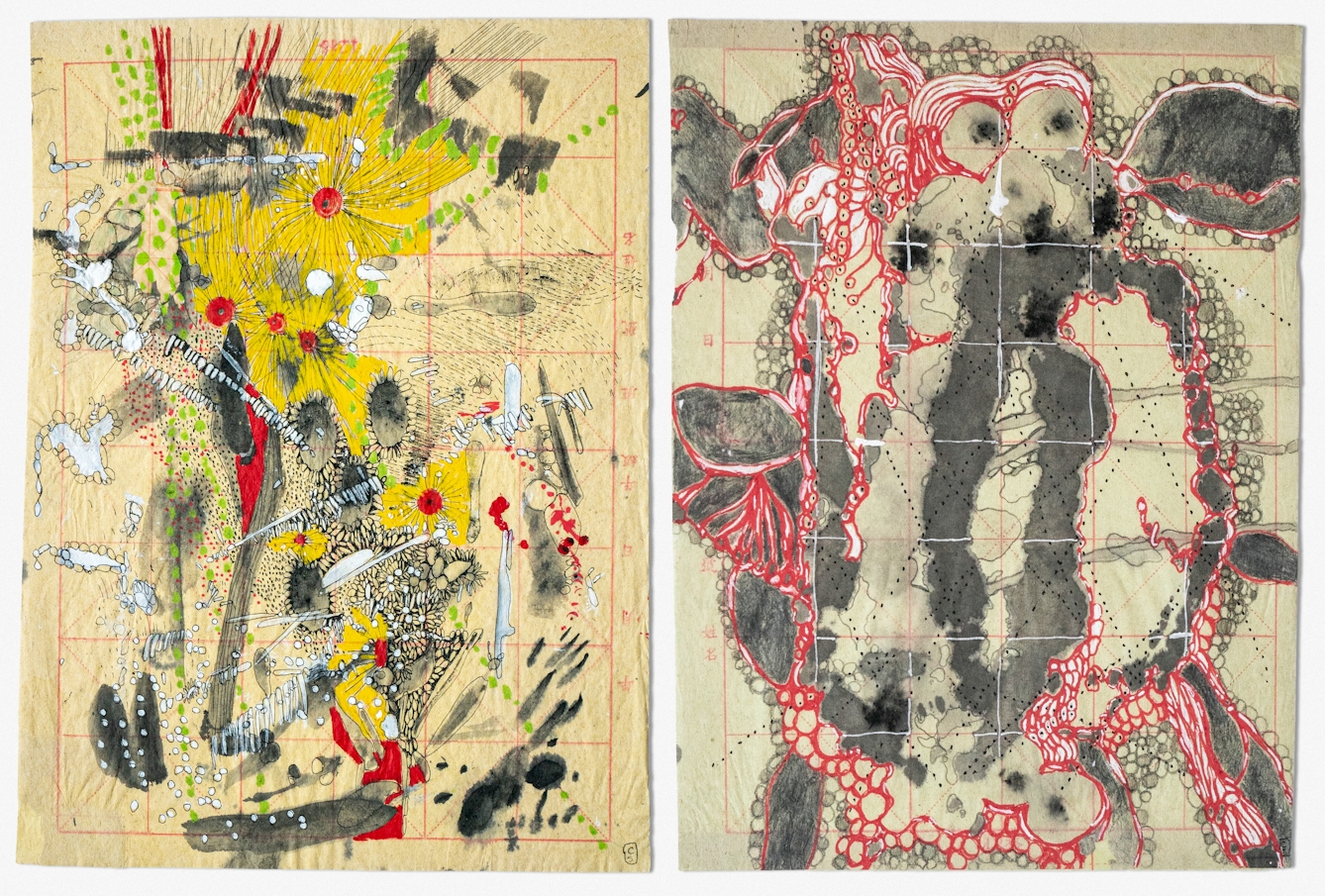

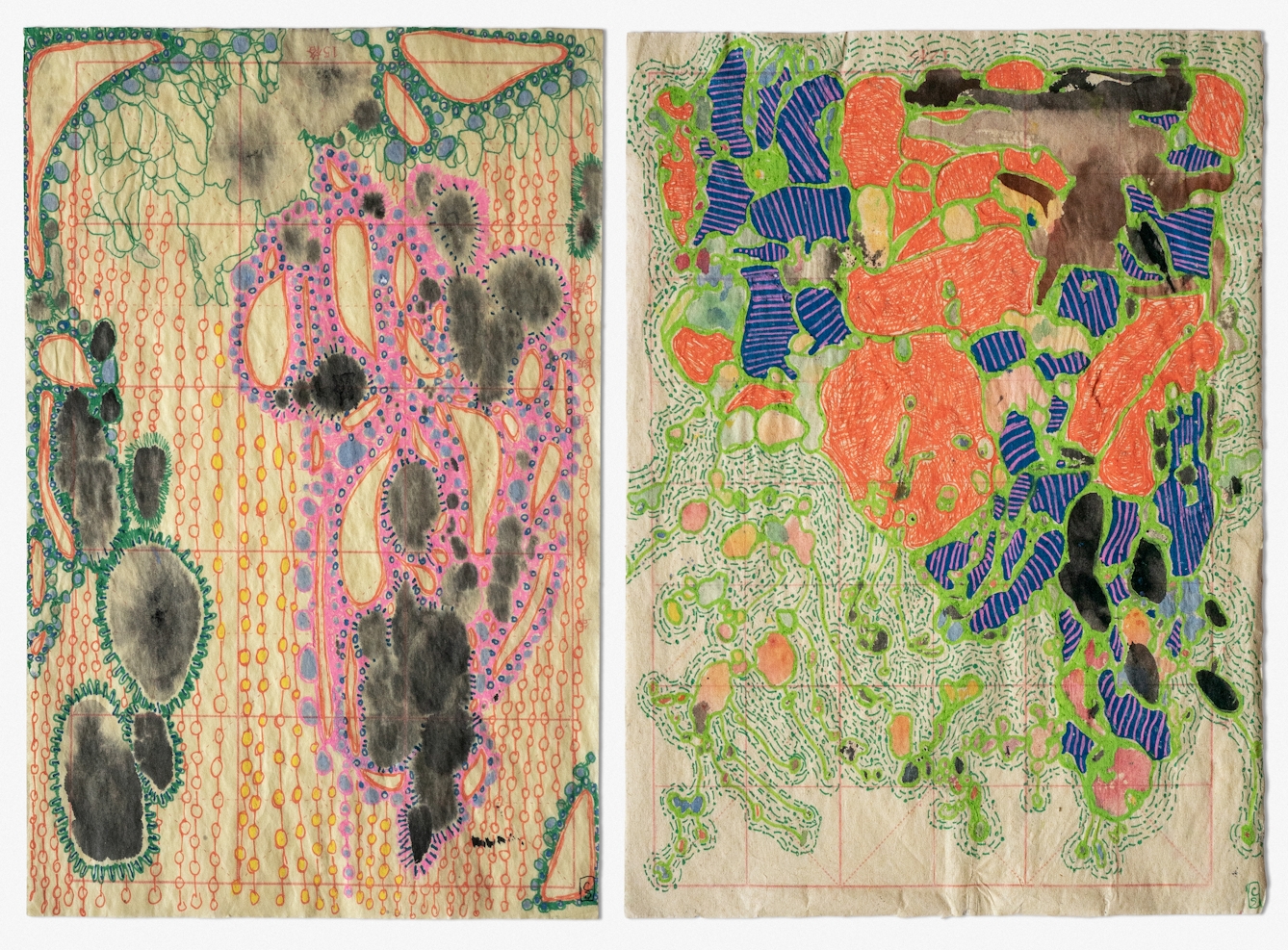

Chemo Day Drawings Series 1, June and July 2019.

What else does an artist do?

I started the drawings out of boredom. I had been playing Scrabble against the iPad and kept winning! So I decided there had to be a better way, as an artist, of spending the time. I started quite tentatively, sometimes doing one drawing, sometimes two. The drawings can at times be quite dense, and at others more open. Occasionally they feel more cellular. As time went on, they became more and more intricate.

The paper is cheap, throwaway paper for practising Chinese calligraphy, for writing. Gridded paper, a nod to modernism and the ubiquitous grid. But the ‘squares’ aren’t quite square. The lines not quite straight. The paper is thin and fragile, but strong at the same time.

There are marks already on the paper. Marks that have bled through from other drawings, in ink, or from coloured marker pens or watercolour paint. The paper tears or I make a hole in it, but it holds together.

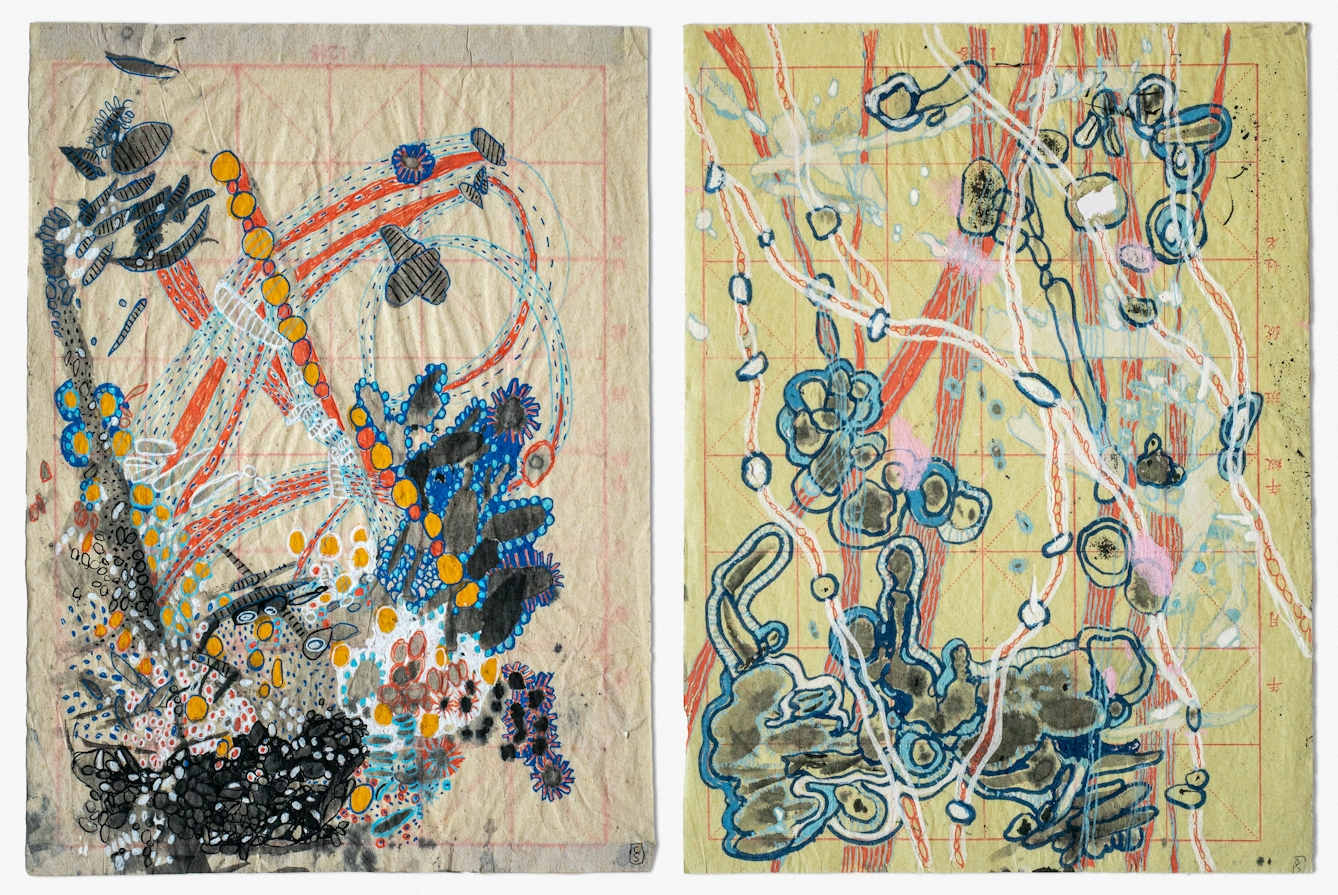

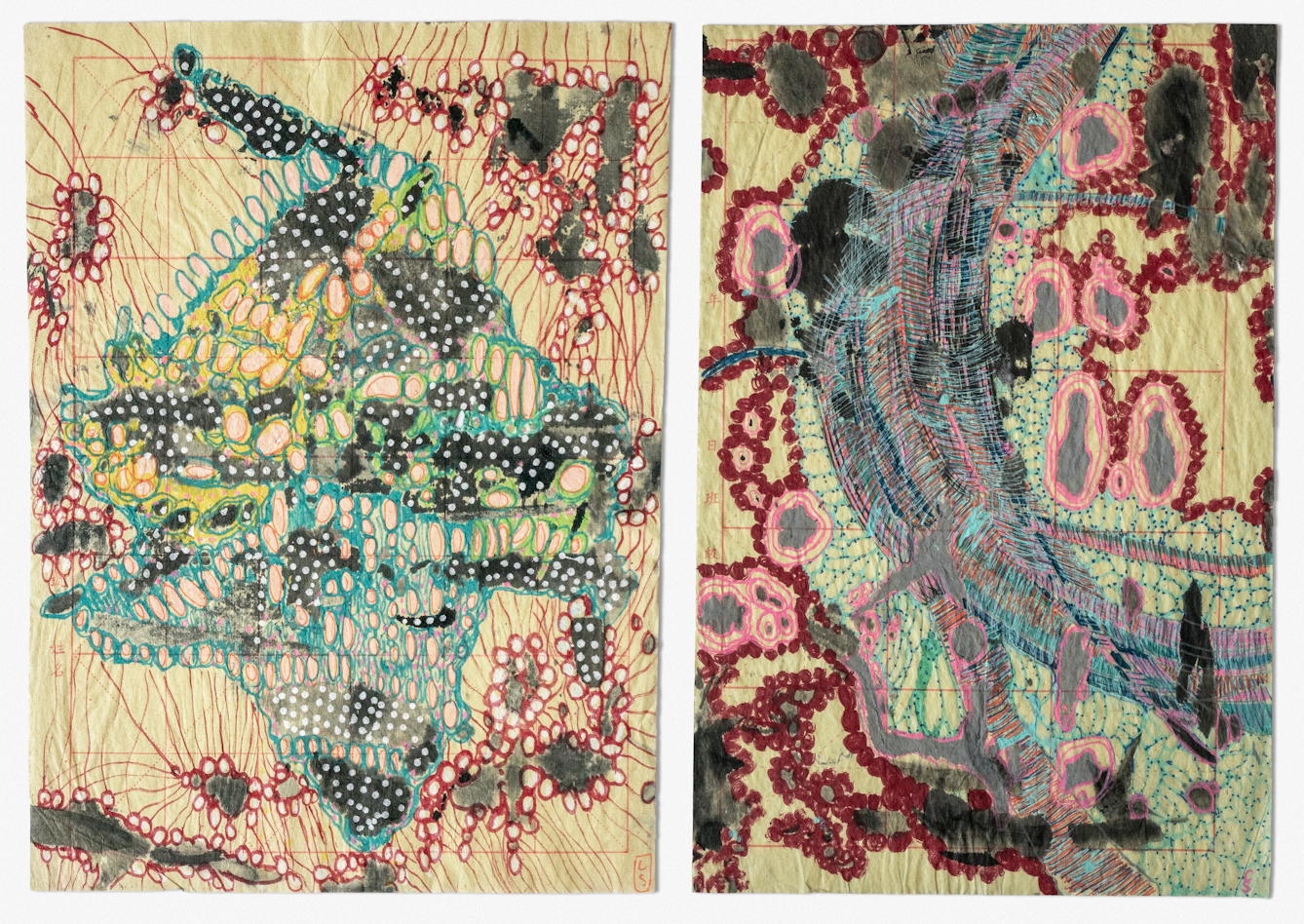

Chemo Day Drawings Series 1, November 2019.

The paper is a place

I travelled a lot as a child, never quite knowing where home was – it certainly wasn’t a place. The paper is a place. Lines appear, areas get filled in. I travel across, change direction. The drawings have been compared to maps.

My life has been shortened, but when I draw, time slows down. These are durational drawings on small pieces of paper that generally took four to six hours to complete.

Not all my work takes this kind of time, but these drawings are as much about time spent as they are about a moment in time, in my life. They are a record of presence, of still being here.

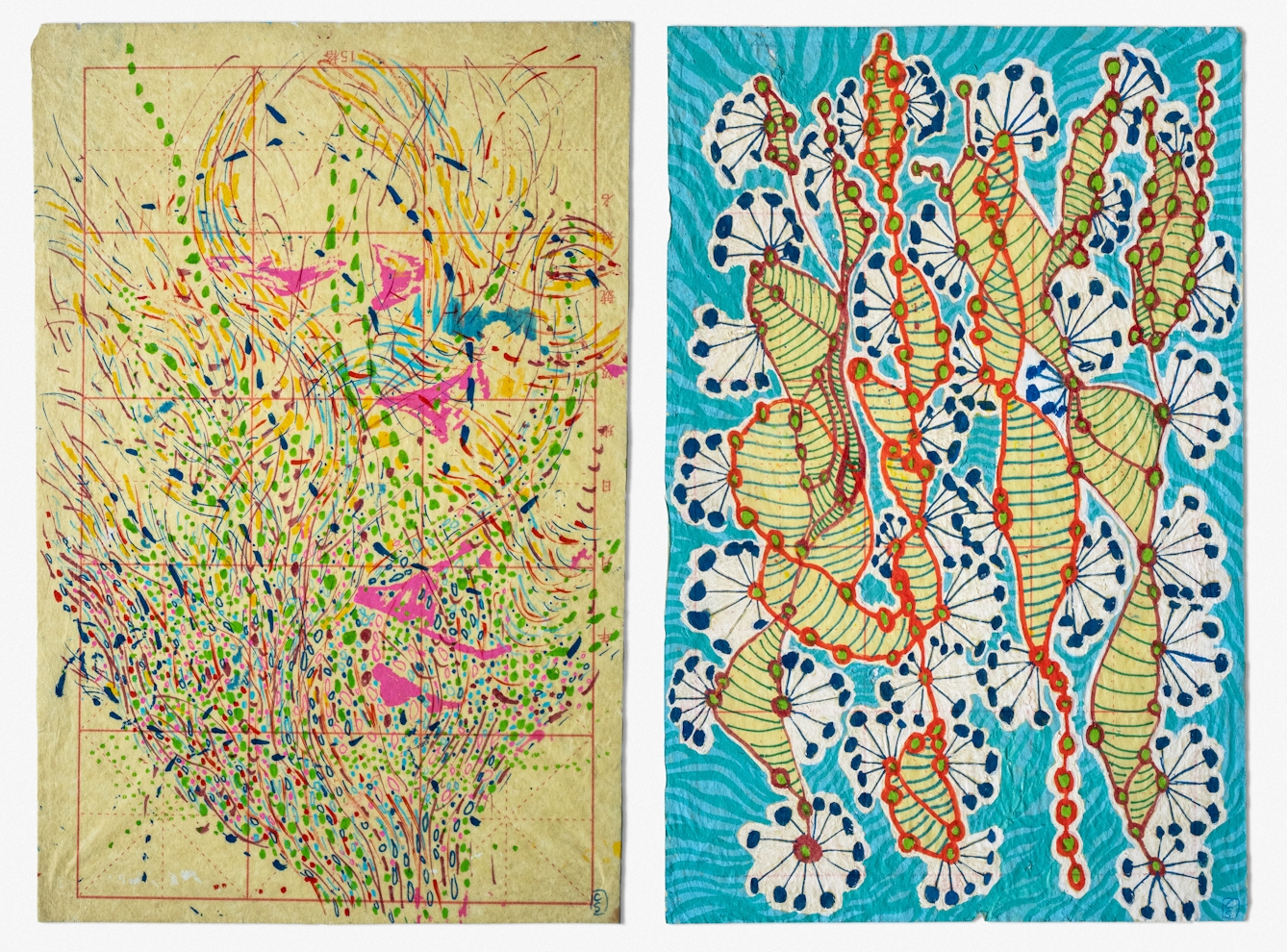

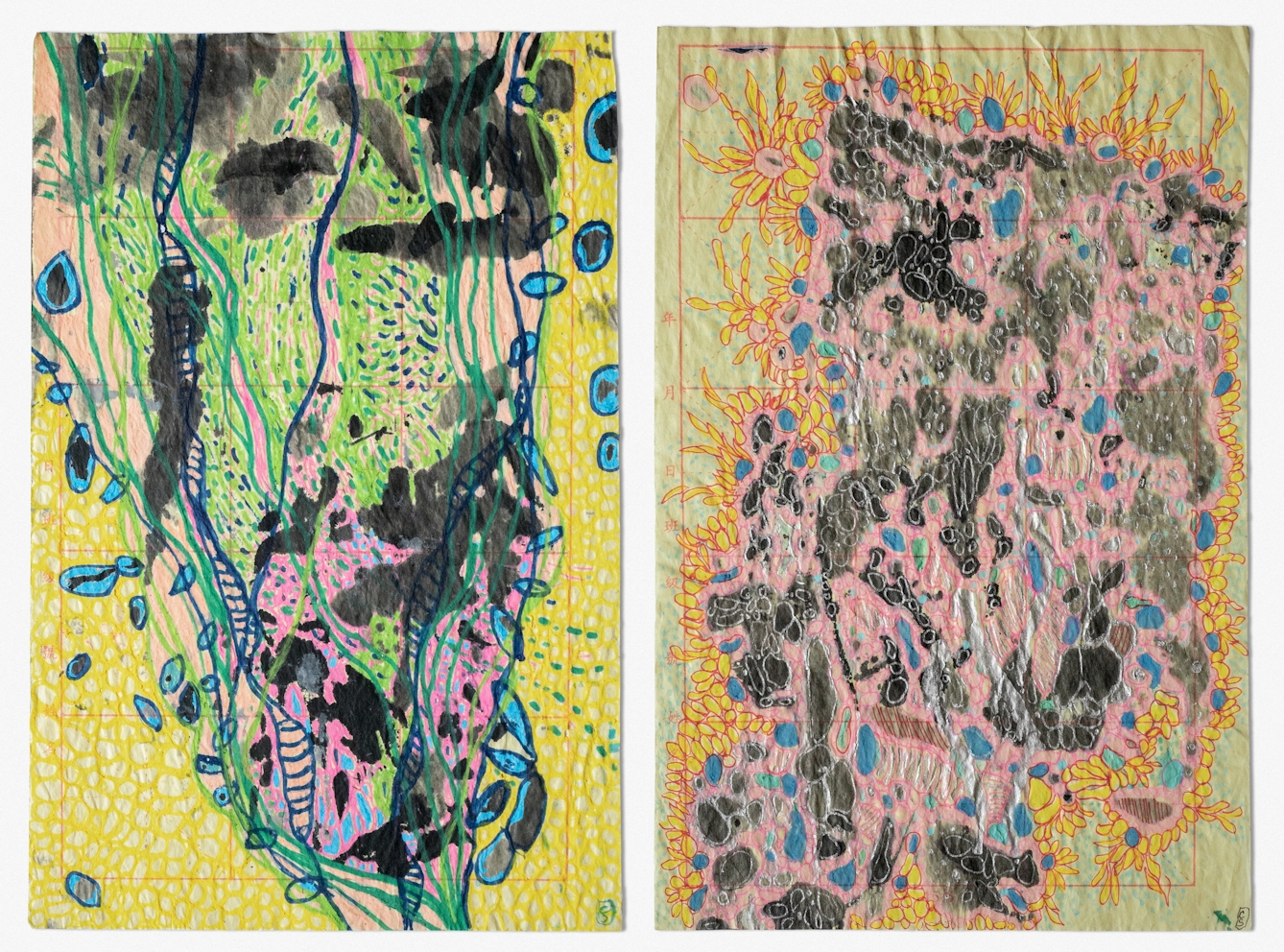

Chemo Day Drawings Series 1, November 2019 and January 2020.

Two cancers

Cancer sounds like it’s one disease. It isn’t. Each cancer has its own cocktail of drugs and limited set of options. The side effects can differ too. I have fortunately not felt too sick, but I do get fatigue – an overwhelming tiredness.

Some treatment sent me to sleep throughout, in the chair itself. The rectal cancer treatment didn’t, so for the drawings I balanced a board on my outstretched legs and had my marker pens within reach on a little side table. It is important that these drawings were done in the chair as a response to site and context.

Something of their abstract, visceral qualities has fed into my other work. It’s as if the visceral signals (from the organs) were transmitted through the body and brain to my hand and into the drawings. The drawings are not about the body but are very much a response to being a body – drawing is a physical, mental and emotional act.

When I said the bowel surgeon was right and wrong about the rectal cancer, it is because no one immediately picked up the fact that my liver tumours were due to secondary breast cancer. One tumour is proving very resistant to treatment, or is “clever”, as my current oncologist says, so my options are running out as I write.

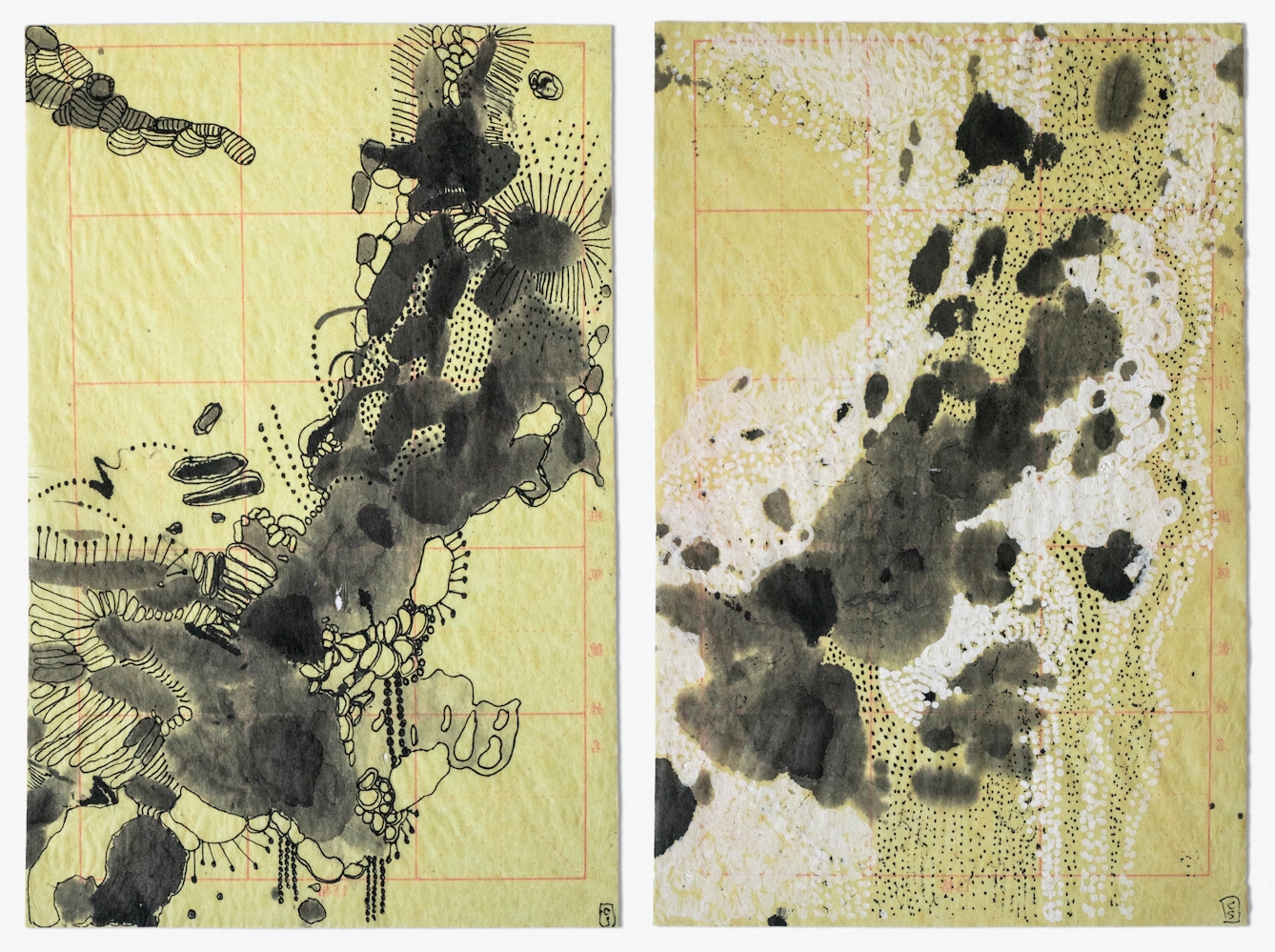

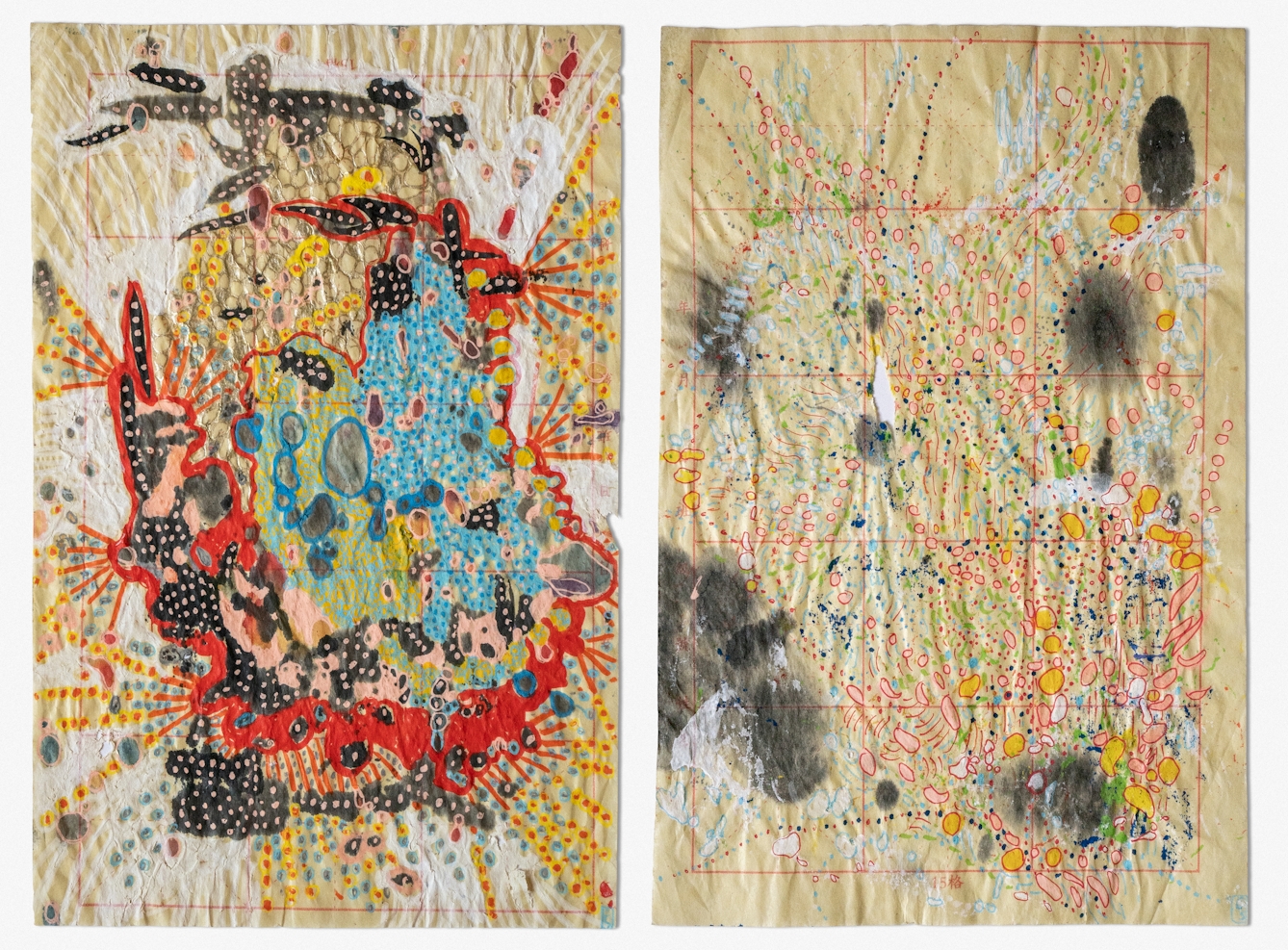

Chemo Day Drawings Series 2, August 2020.

The chemotherapy treatment chair

The treatment rhythm depends on the chemo you get, but there is always pre-chemo two days before, which involves a blood test and checking on side effects. The treatment chair is a chunky blue recliner. Usually there is a pillow on one arm of the chair to rest your arm on while having the various flushes and intravenous treatments.

This is all set up by the nurses, who are absolutely wonderful: compassionate, caring and generally only up for conversation if you are.

Chemo Day Drawings Series 2, September 2020.

Treatment during Covid

When Covid first hit, no one knew quite what to do. The then consultant, clearly working to a script, very mechanically told me I had to have a six-week treatment break before going on to new drugs. I was lucky in that I was still able to have treatment when so many cancer patients across the country were having to go without.

Before Covid, Roger would sit on a small chair next to me while the dog was at daycare. Now patients have to attend on their own unless they need a carer with them, although an exception is made for consultant’s appointments. So Roger waits for me, with the dog, outdoors, often fitting in a walk in the nearby woods.

Chemo Day Drawings Series 2, October 2020.

Visits to A&E

A & E is somewhere you do not want to go to while receiving cancer treatment, but a high temperature means you will be sent there. I’m sure the uncomfortable chairs are meant to keep you away unless you really have to be there. Once I ended up in A & E after the GP, over the phone, diagnosed an allergy causing my reddening middle finger and hand. The 111 on-call doctor suspected cellulitis.

In fact, it was a massive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) flare. I felt stupid not to have recognised it after all these years. I’ve had RA since I was 19. I sat on the hard chairs, some of them broken, until the nurses found a three-quarter-length sofa for me and one other patient, which was difficult to sleep on, especially as I find it impossible to curl up.

The regular trips to hospital, the exhausting effects of the treatment, the A&E ‘scares’ take their toll. Sometimes I just want to curl up and sleep and I can’t always find the emotional bandwidth I used to be able to find for supporting others.

Chemo Day Drawings Series 2, November 2020.

Suspected sepsis

The most recent A&E event was again due to a high temperature. On the day of my pre-chemo blood tests, I went back to bed after breakfast, feeling unwell, and rang the cancer day unit to postpone my appointment until the afternoon. I got very hot in bed and thought it was because I had too many clothes on.

I measured my temperature and it was nearly 39 degrees, but came down a bit. I got to the unit and my temperature seemed OK until I was about to leave, when I said I felt cold. Turned out my temperature was over 38 degrees again, so I was sent to A & E. I was diagnosed with suspected sepsis and put on IV paracetamol and at least four drips.

I had become a body in distress. It’s strange to be so in the body or to just be the body, that all you are is a kind of moan, rocking yourself for comfort, and longing for a bed.

Chemo Day Drawings Series 2, December 2020 and January 2021.

From scan to scan

Over time I have become used to the rhythm of the 12-weekly scans. After each scan I feel apprehensive and sometimes dare to be hopeful, though my luck is running out now. Sometimes the scan reports have been encouraging, but there have also been the “not the result we were hoping for” moments, followed by new treatment and lots of finger-crossing.

I am on my last chemo options now. It isn’t that I am scared of dying. I think when the time comes, the process will be managed such that I get sleepier and sleepier and then slip away. I hope so, at least.

I do, though, feel sad and disappointed that I have to scale back my hopes for sharing and showing my work. I have missed opportunities to show it physically and have missed going to exhibition openings and opportunities to see other artists’ work in the non-Zoom world.

Chemo Day Drawings Series 2, January and February 2021.

Keeping going

After the diagnosis, Roger and I made sure we had done our wills. I gave away some things that I’d have given away later anyway, like some pieces of jewellery and books. Being pragmatic is a way of getting my head around things and I suppose there is a sense of being “in control”.

I keep going thanks to Roger, my friends and my family. And by continuing to draw. I do wonder whether the world needs more work by me. But then, I suppose, I make the work because that’s what artists do.

About the artist

Clare Smith

Clare Smith was born in Penang, Malaysia. She works from a studio in Dover. She has an BA from the University for the Creative Arts (UCA) and MA from the University of the Arts London (UAL, Central Saint Martins). She is co-founder of Dover Arts Development (DAD), together with Joanna Jones. Clare Smith was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 2010 and then unlucky to be diagnosed with bowel cancer in 2018 and then secondary breast cancer in 2019. As an artist, making drawings while undergoing treatment has been an important part of coping with being ill.