Electrified humans brought education and performance together with a spark in the 18th century.

Charged bodies

Words by Ruth Gardeaverage reading time 4 minutes

- Serial

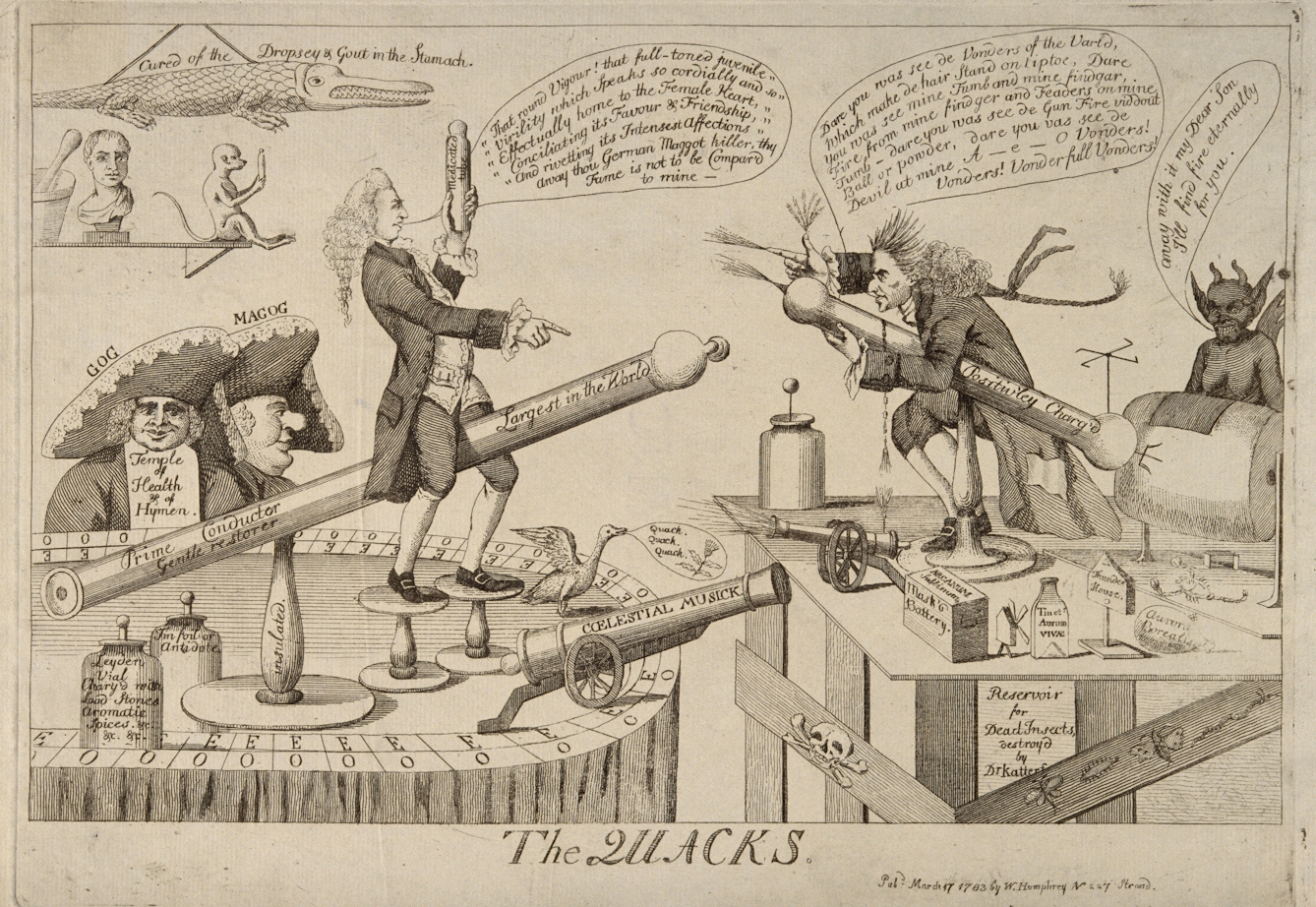

James Graham and Gustavus Kattefelto, both electrical ‘showmen’, were regarded as quacks by contemporary commentators.

Eels had become unwitting performers in demonstrations of natural electricity after the 1770s, but the human body had been an indispensable element in public displays of artificial electricity since the 1730s. Enthusiasm for such displays was widespread – in 1745 the Gentleman’s Magazine reported that such phenomena “were so surprising as to awaken the indolent curiosity of the public… who never regard natural philosophy but when it works miracles”. Indeed, even “princes were willing to see this new fire which a man produced from himself, and which did not descend from heaven”.

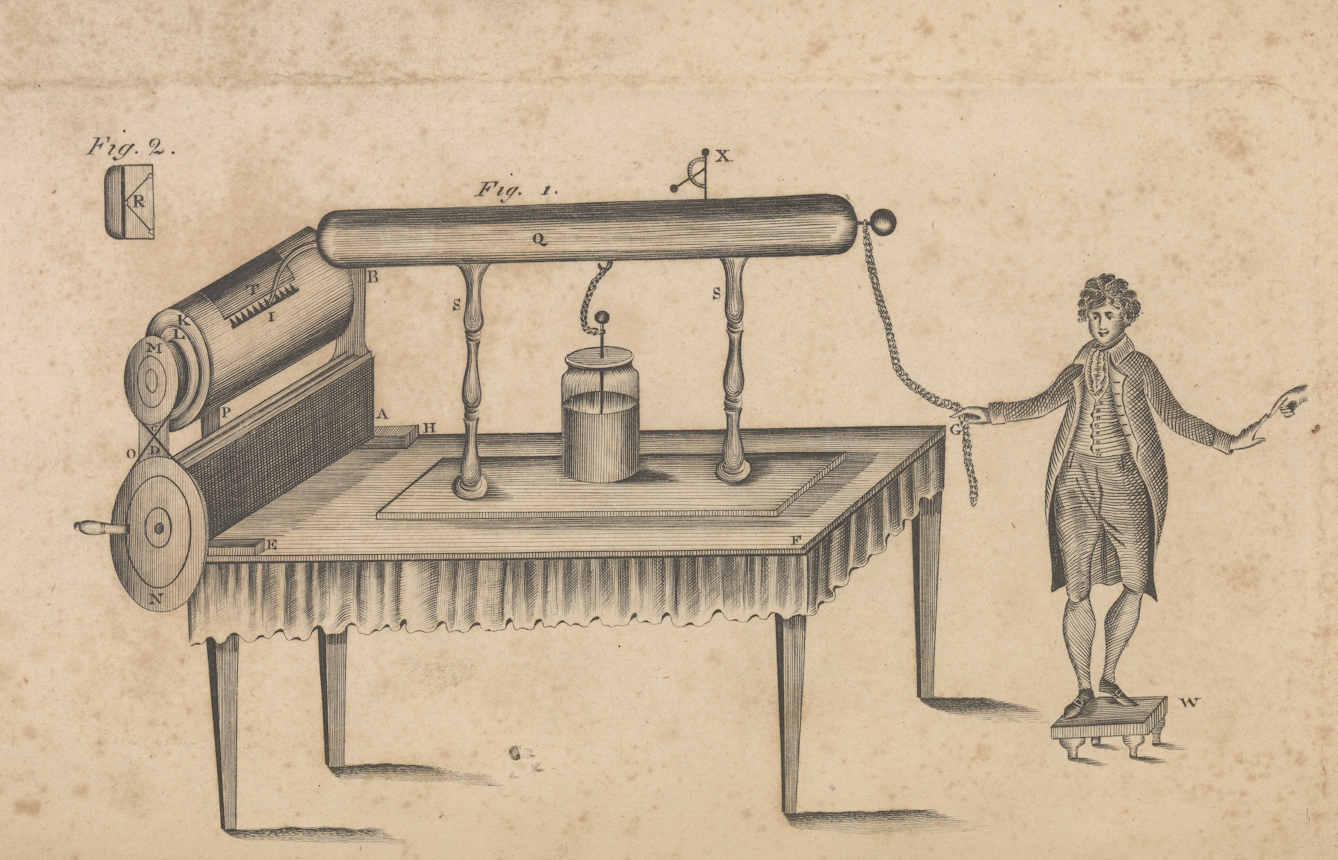

The first person who “ventured to electrise men” was Stephen Gray, a Royal Society Fellow, who devised the famous “flying boy” experiment. A boy suspended from the ceiling with silk cords was connected by the feet to an electrostatic generator. This created a charge in the boy’s body, by which he attracted small pieces of paper and other light objects or turned the pages of a book with his electrified hands.

Other experiments and demonstrations required the participation of the audience itself. The French instrument-maker and natural philosopher Jean-Antoine Nollet performed experiments with Leyden jars in which chains of people would hold hands and be shocked simultaneously, as the first and last person in the human circuit touched the inside and outside coating of the jar.

In pictures

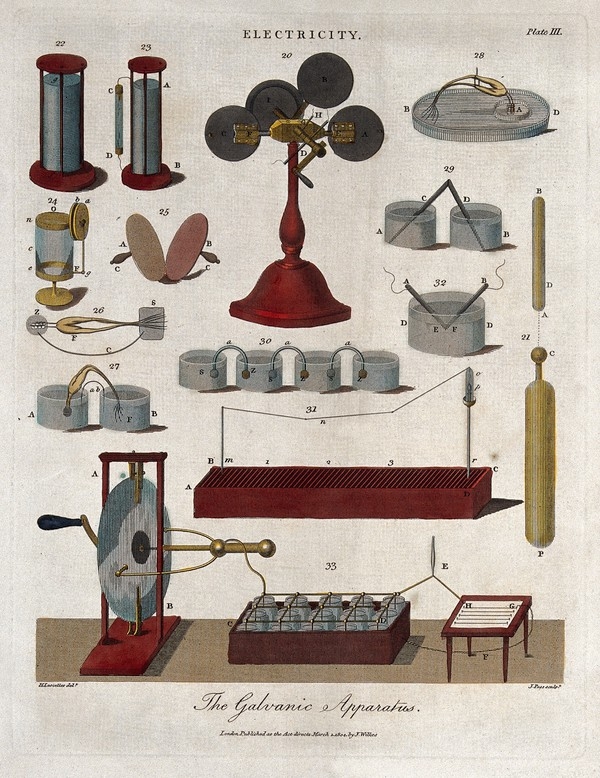

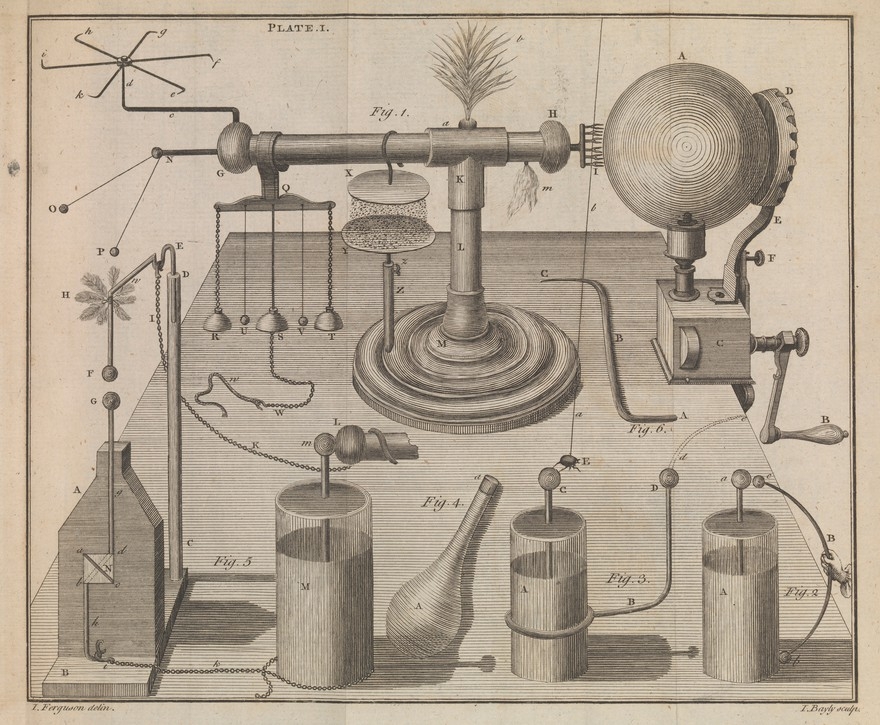

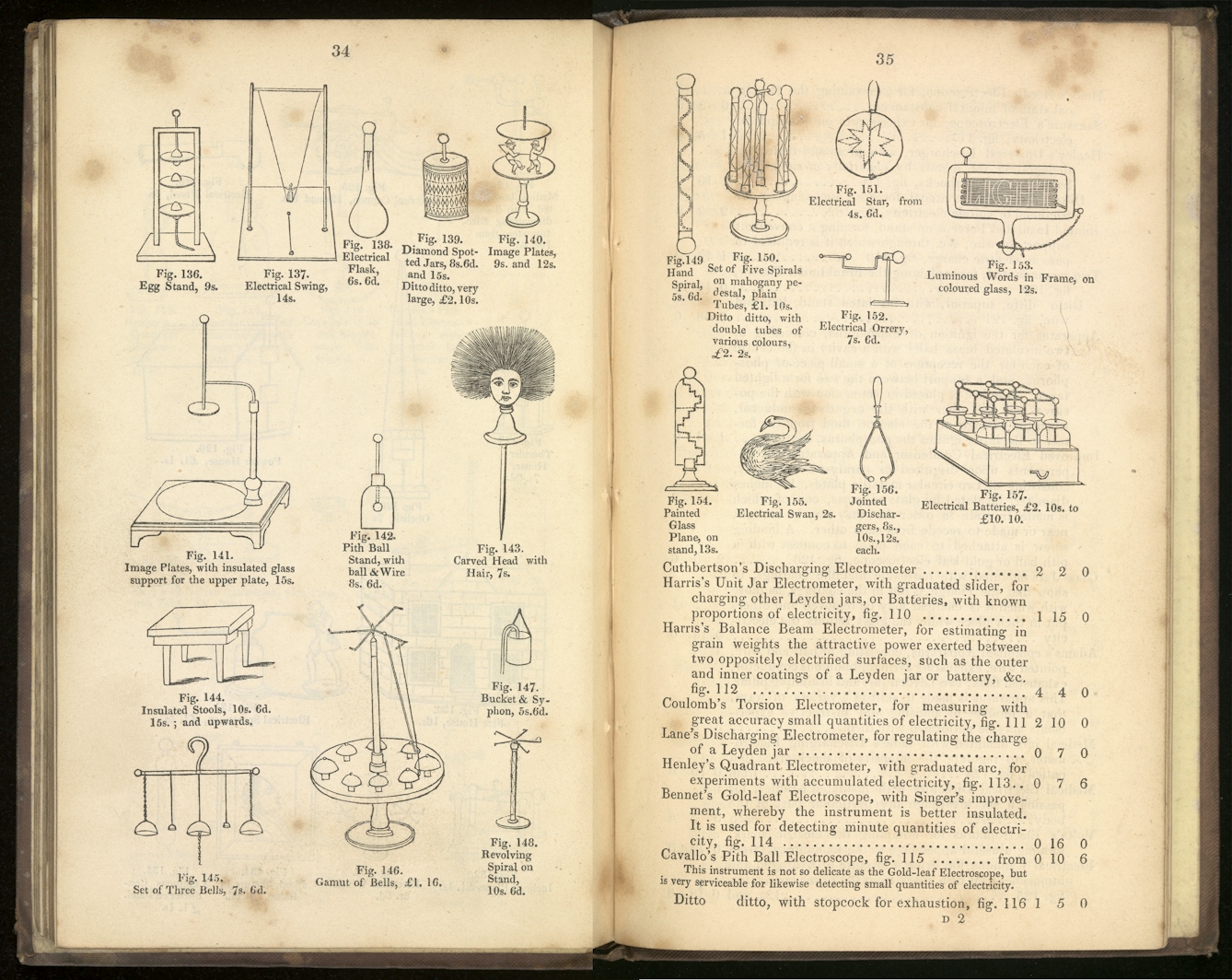

This 1804 illustration from ‘Encyclopaedia Londinensis, or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature’ suggests the equipment itself formed part of electricity’s fascination.

Part of the appeal of electrical demonstrations was their undeniable frisson of danger for participants.

James Ferguson wrote his ‘An Introduction to Electricity’ so that others might copy his experiments “for their own amusement and that of their friends”.

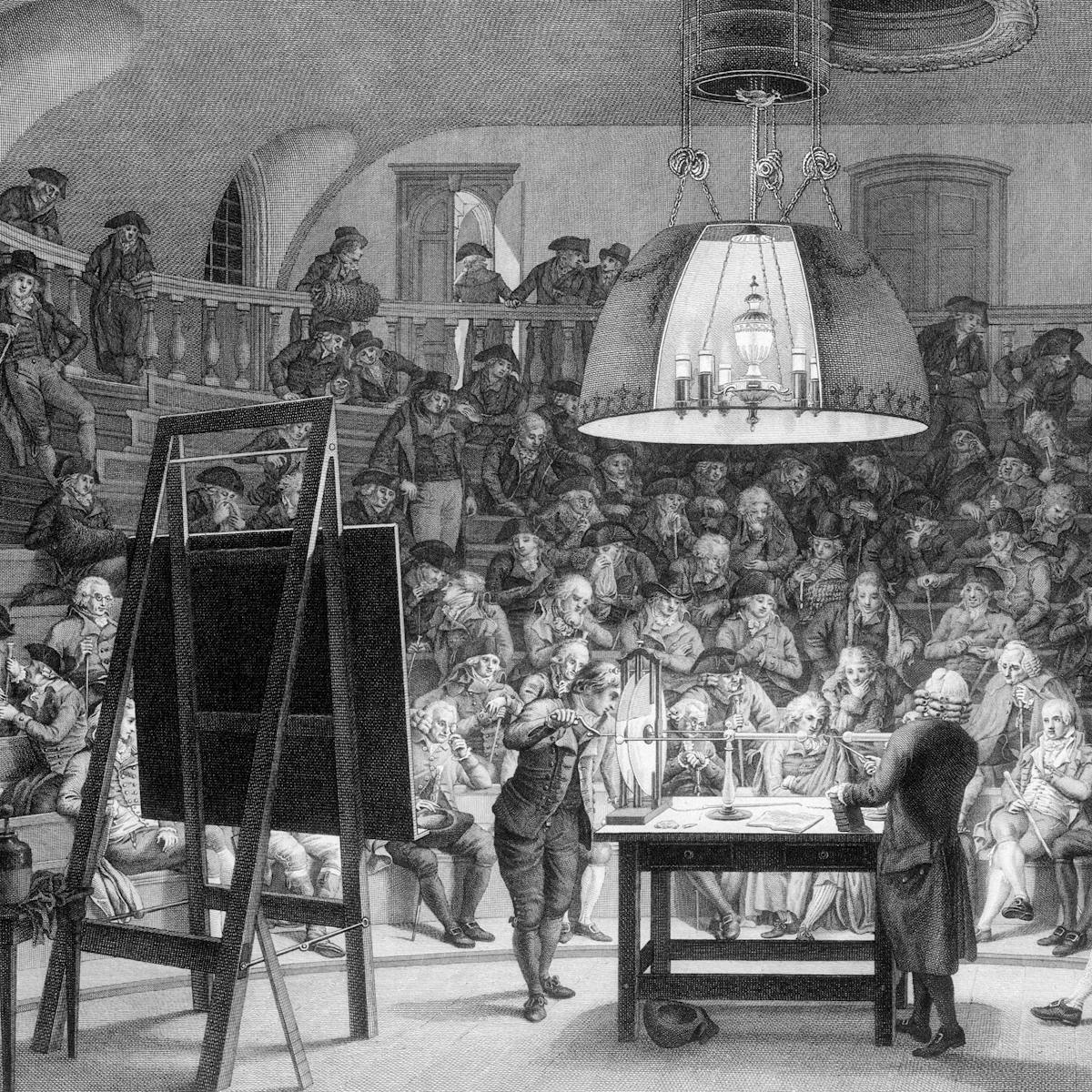

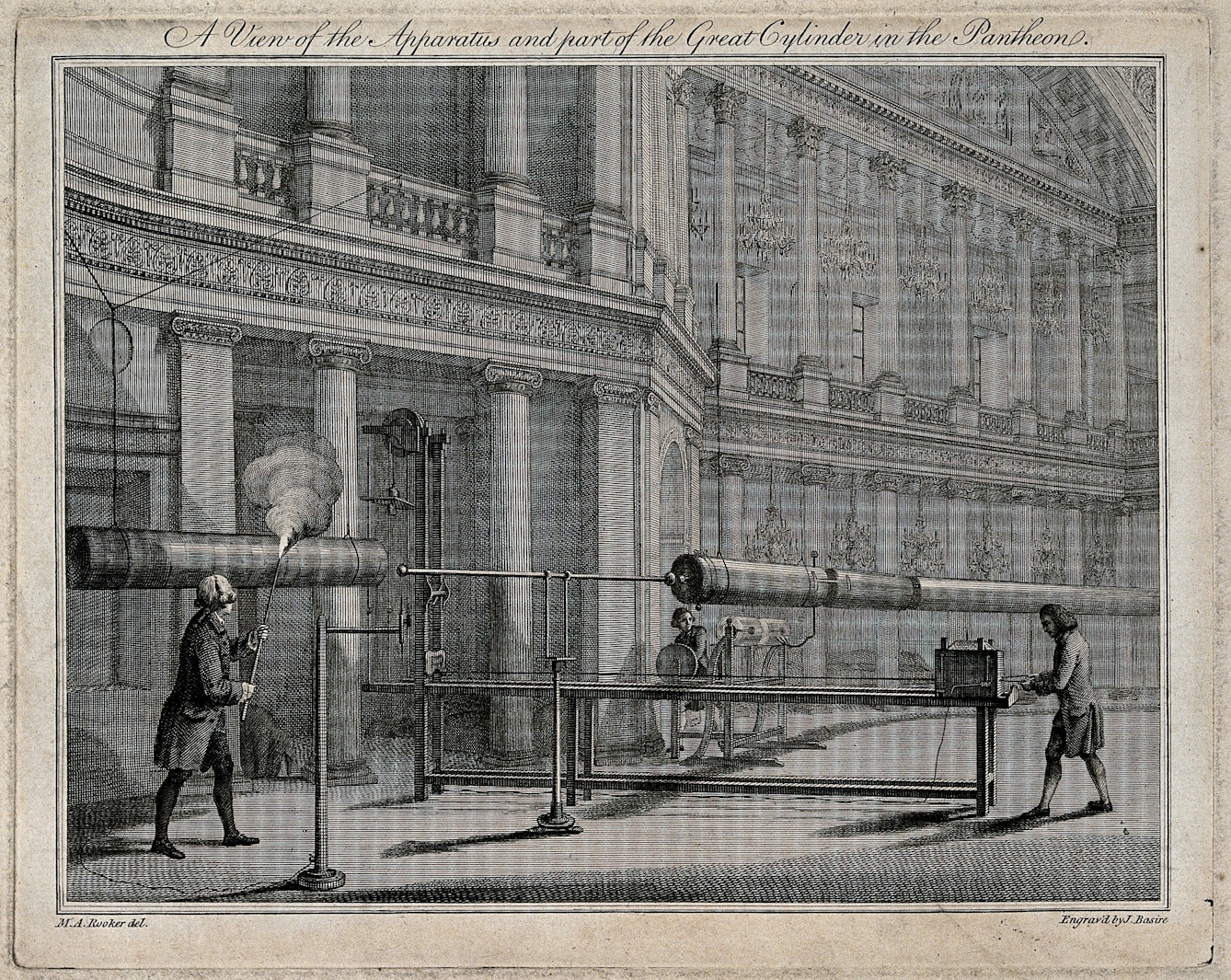

This illustration probably depicts Benjamin Wilson’s electrical demonstration of 1777 for King George III.

The leading London electrical demonstrator William Watson performed a variation on this theme in a dramatic intervention in the urban landscape. He connected a Leyden jar to a 1,200-foot wire, laid across Westminster Bridge. A man held one end of the wire and touched the water of the river; on the opposite bank a second man held the wire and the Leyden jar, while a third touched the jar and the water. In completing the circuit all received a shock.

In the private realm of the salon, often darkened to enhance the theatrical ambience, German electrician Georg Bose invented the fanciful ‘Venus Electrificata’ experiment. A lady from the audience was invited to stand on an insulating stool, where she would receive a charge from a friction machine. A gentleman was then invited to attempt to kiss her, only to be painfully repulsed by an electrical discharge from her lips.

In pictures

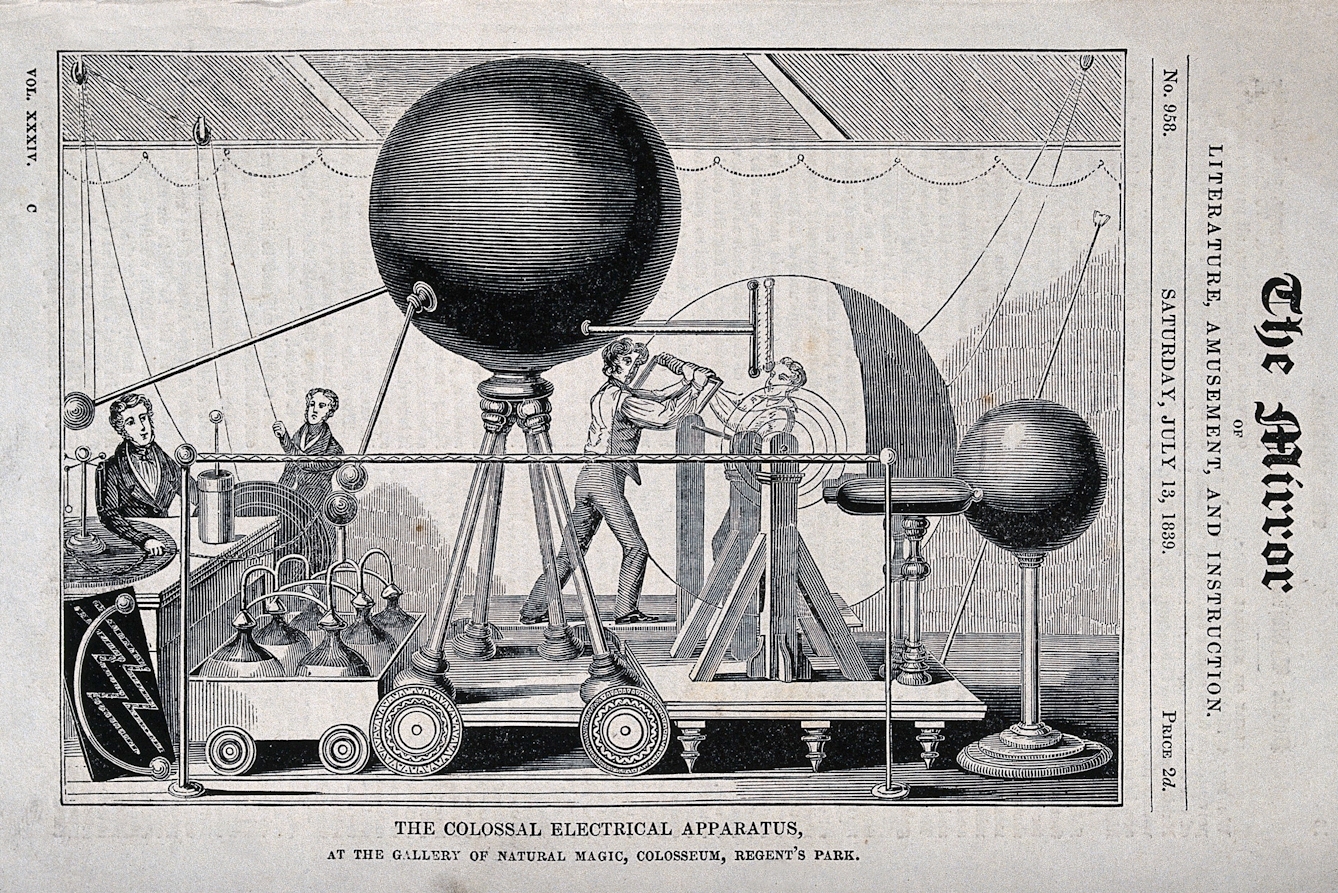

In 1839 the ‘Yearbook of facts in science and art’ described this apparatus as “the largest in the world”, giving a length of spark “hitherto deemed unattainable”.

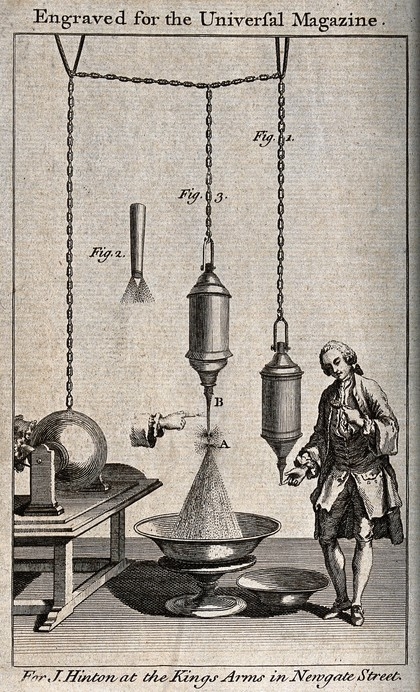

This plate featuring an electrostatic generator, with a Leyden jar and a demonstrator standing on an insulating stool, is one of the first illustrations of complete electrical apparatus published in North America.

This parodic poem satirising James Graham is an example of the many ways in which his perceived quackery was publicly mocked.

Along with electrical instruments, Palmer’s catalogue also included toys such as the “electrical swan”, which swam about when placed in electrified water.

In this demonstration the boy is about to touch the rod, which will discharge an electric shock. The audience watches expectantly.

Such performances engaging bodily sensation heightened the audience’s experience of drama, wonder and astonishment. But they did not only thrill, they also aimed to educate. The scientific instruments devised for and employed in demonstrations were put to investigative as well as entertaining use. Demonstrations also helped stimulate the design, manufacture and ultimately advertising of electrical instruments and gadgets.

The 18th-century craze for electrical performance also provided fertile ground for more dubious practitioners, such as the renowned quack James Graham. Graham, a self-styled specialist in sexual health, opened his Temple of Hymen in Pall Mall in 1781. Its centrepiece was the Celestial Bed, which he claimed could help couples with marital and fertility problems. Its chief ‘remedy’ was based on static electricity: the bed was insulated by glass rod supports, which allowed it to become charged.

According to Graham, the charged atmosphere was “calculated to give the necessary degree of strength and exertion to the nerves” and the users’ charged bodies could ejaculate fluids more vigorously. Rental of the bed was an eye-watering £50 a night and was guaranteed to bless its users with progeny. For desperate couples this was no joke: here electricity was touted as a force that could heal and bring forth life.

Though the sparks, shocks and haloes of electrical demonstrations elicited amusement and wonder, there was also room for fear and unease. Some attendees of electrical soirées refused to participate for fear of being electrified. Just as the untamed natural electrical phenomena of thunder and lightning prompted terror and awe, manmade electricity had a similarly perilous potential. Developments in the later 18th and 19th centuries would further emphasise the disquieting connection between electricity and death.

About the author

Ruth Garde

Ruth Garde is a freelance curator and writer, focusing on the fields of history, art, architecture and heritage. Over the past fourteen years she has worked extensively with Wellcome Collection, writing and curating a variety of projects encompassing history, human health, art and science.