It’s not unusual for captives, like kidnapped student Patricia Hearst, to end up feeling strong bonds with their captors. But is it a matter of submission or survival?

Can our minds be taken hostage?

Charlie WilliamsSarah MarksDaniel Pickaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

In 1973, during a bank robbery in Stockholm, Jan Erik-Olsson took four bank employees hostage and held them for six days, tormenting them with the threat of dynamite and hanging. Yet when they were released, some refused to cooperate with the investigation or to testify against him in court. Not only that, some actively contributed to the financial cost of his defence and appeared to believe that their captor was in fact humane and protecting them from the police. Swedish psychiatrists described a new type of mental disorder: Stockholm Syndrome. The term has since become widely used, yet its meaning remains obscure and often debated. How can such bizarre, irrational behaviour be explained?

On August 26, 1973, Norwegian police lowered a camera through a hole drilled in the roof of Kreditbanken at Norrmalmstorg Square, Stockholm. Here, three hostages are seen with their captor Jan-Erik Olsson (standing on the right).

Situations where individuals identify with dominant and malevolent authority figures have long interested psychiatrists. In the early 1930s, the psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi described paradoxical emotional attachments he observed in survivors of child abuse as ‘identification with the aggressor’. The overwhelming trauma and anxiety of abuse, argued Ferenczi, could leave children physically and morally helpless, subordinated ‘like automata’ to their abuser’s will.

During World War II, Austrian psychotherapist Bruno Bettelheim used Ferenczi’s concept to explain the behaviour of prisoners held in Nazi concentration camps. Bettelheim himself had been imprisoned between 1938 and 1939 in Buchenwald and Dachau. In 1943 he described several cases in which prisoners appeared to identify with Gestapo guards through both their behaviour and attitudes. Some prisoners adopted the guards’ manner of speaking and even imitated their dress and leisure activities. Bettelheim described the camp as a laboratory that turned “free and upright citizens not only into grumbling slaves, but into serfs who in many respects accept their masters’ values.”

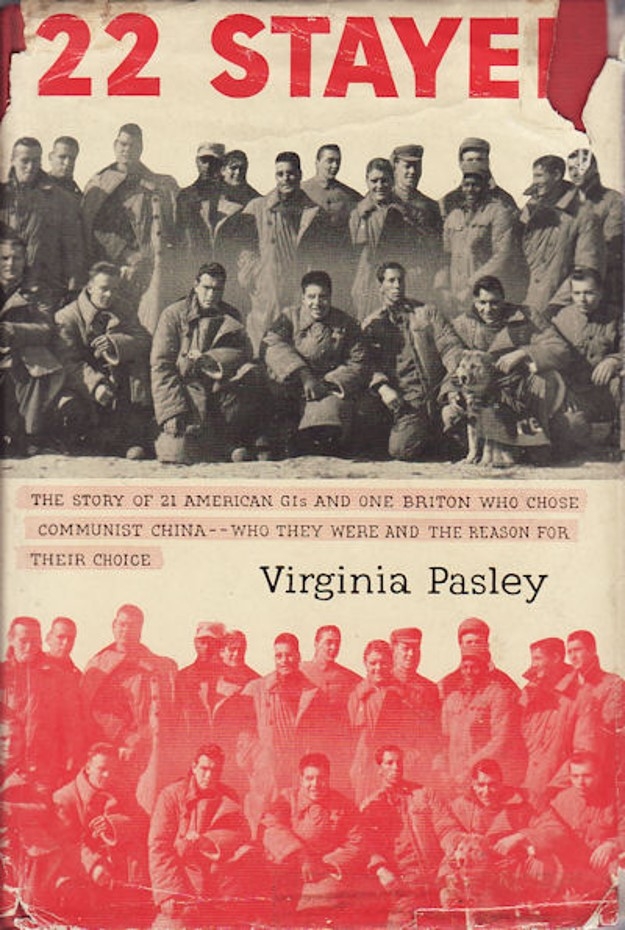

Six of the twenty-one American soldiers who chose voluntary non-repatriation after the Korean War pose for a photograph.

Prisoners cooperating with the enemy became an urgent political problem for the United States government during the Korean War, as reports emerged of American prisoners of war collaborating with their Chinese and North Korean captors. In 1953, Colonel Frank Schwable and 35 other US Air Force personnel falsely confessed in public to committing crimes of bacteriological warfare against North Korea. Other reports of collaboration included passing information to the enemy, cooperating with indoctrination and making anti-war broadcasts. When the war was over, one British and twenty-one American soldiers chose to relocate to Communist China rather than return home.

Virginia Pasley's ‘21 Stayed’ (US) and ‘22 Stayed’ (UK) investigated the lives and experiences of those British and American soldiers who chose to stay in China after the war.

The US Army and Air Force established a panel of psychologists to investigate this psychological indoctrination, or ‘brainwashing’. I E Farber, Harry Harlow and Louis Jolyon West proposed a model based on learning theory and conditioning. They claimed that a combination of sleep deprivation, solitary confinement, malnutrition and threats created a state of debility, dependency and dread (DDD). The careful manipulation of DDD could induce a state of consciousness so intolerable that captives would reorganise their values and behaviour to suit their captors’ demands. The key to successful brainwashing was to provide occasional relief by rewarding good behaviour. If applied correctly, it could lead to ‘complete compliance’.

The most junior of these three researchers, Louis Jolyon West, would gain a reputation as an expert on the science of brainwashing and altered states of consciousness. He was particularly outspoken in his support for Korean War POWs, who had been accused of being weak-willed traitors and unfit soldiers.

Brainwashing on trial

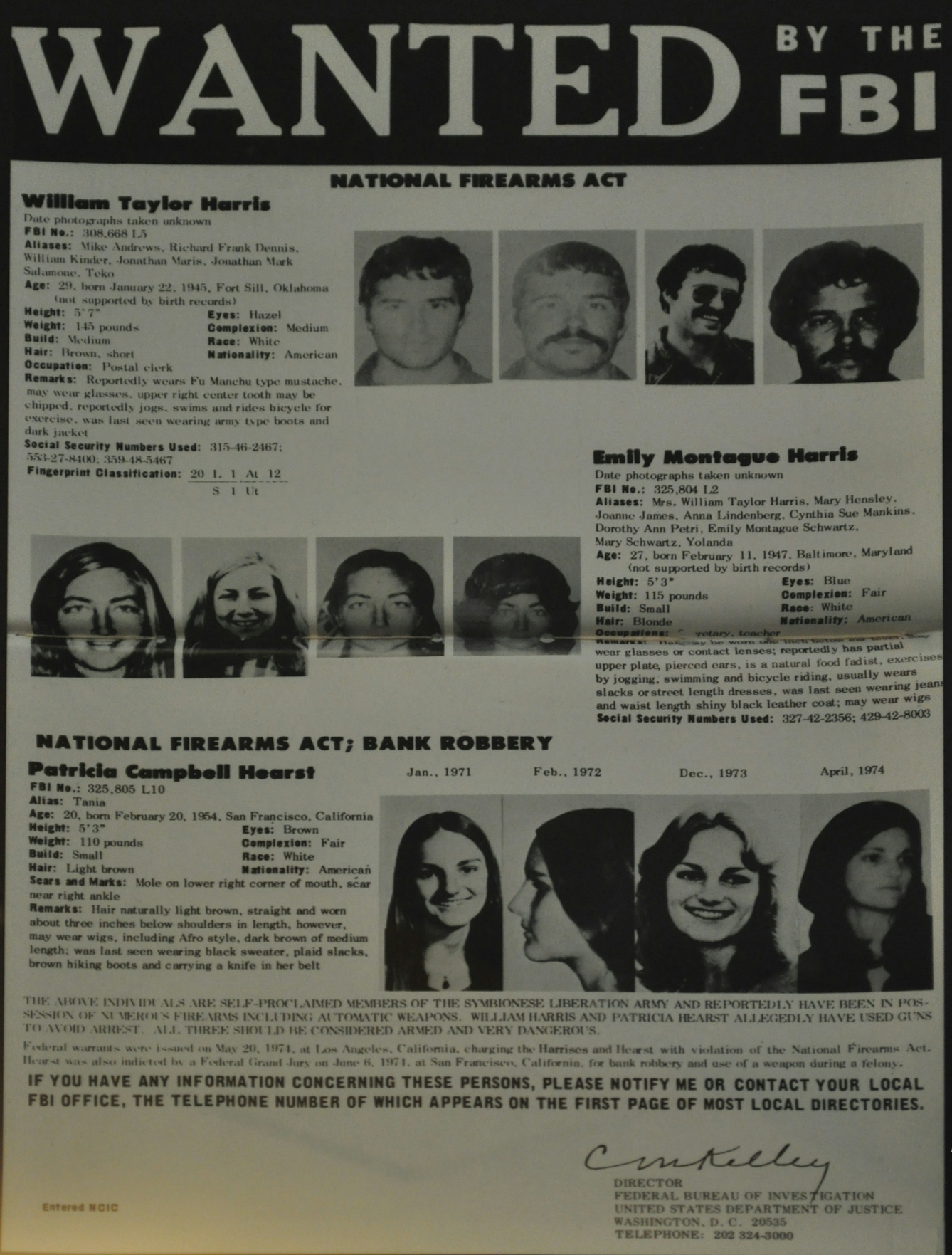

West was one of four expert witnesses in one of the most high-profile hostage cases of the 20th century. In 1974, 19-year-old Patricia Hearst, granddaughter of American media tycoon William Randolph Hearst, was kidnapped by a radical left-wing urban guerrilla group known as the Symbionese Liberation Army and subjected to isolation, threats and sexual abuse. Hearst changed her name to Tania and became supportive of the group’s cause. After 19 months she was arrested and charged with participation in an armed robbery on a bank. She was photographed in handcuffs giving a clenched-fist salute and listed her occupation as ‘urban guerrilla’ on police forms.

Her 1976 trial was a public sensation. The transformation from media heir to gun-wielding revolutionary raised questions about the fragility of the self in 1970s America. Was she, as the prosecution suggested, “a rebel in search of a cause” or a victim of psychological manipulation?

Hearst’s legal team assembled a panel of psychiatrists with expertise in treating Korean War POWs as well as former members of cults. West’s expert testimony likened Hearst’s situation to that of the Korean War POWs he had interviewed in the 1950s. He reported that she experienced similar conditions of debility, dependency and dread, which made her “numb with terror”, such that she “complied with everything they told her to do”, and he observed dissociative symptoms, such as anxiety, memory loss and depersonalisation consistent with DDD, leading to a “diminished capacity for autonomous action”. His account was supported by the testimonies of Robert Jay Lifton, Margaret Singer and Martin Orne, who also described her condition as a classic case of coercive persuasion.

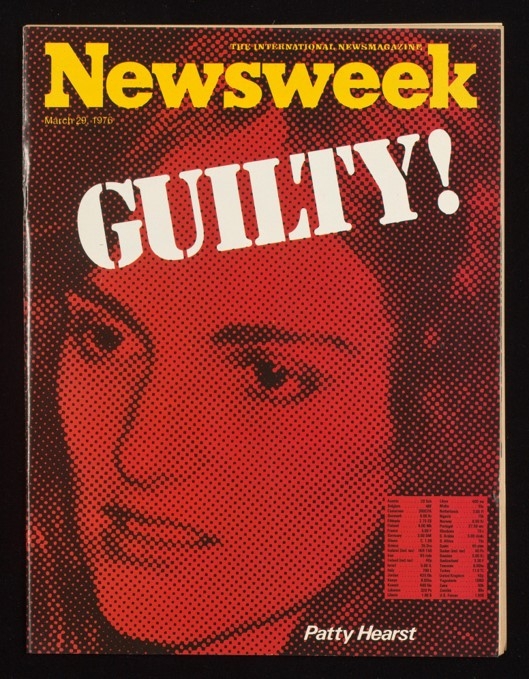

Patty Hearst

The story of Patricia Hearst was a public sensation and was widely reported in the US and international media. On April 29, 1974, she appeared on the front cover of Time.

“The above individuals are self-proclaimed members of the Symbionese Liberation Army and reportedly have been in possession of numerous firearms including automatic weapons.” A 1974 FBI wanted poster with descriptions and photographs of husband and wife William and Emily Harris (alias Teko and Yolanda), and Patricia Hearst (alias Tania).

Patty Hearst poses for the press with a closed-fist salute, shortly after her arrest in San Francisco, September 18, 1975.

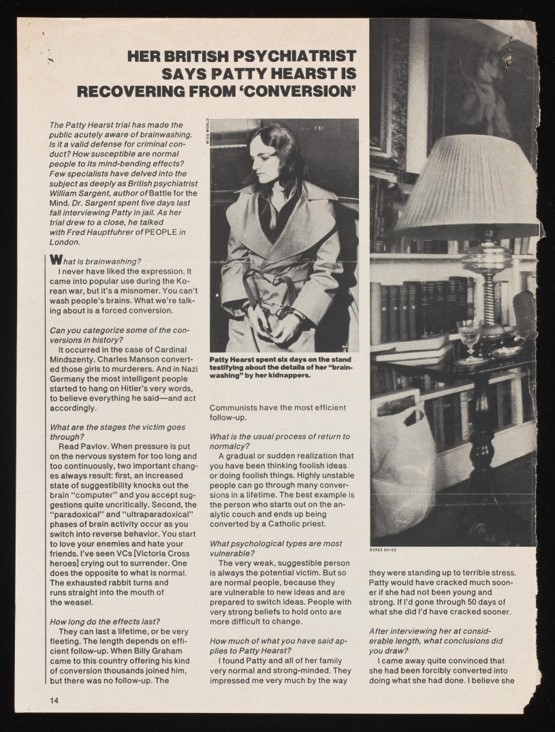

Following her arrest, Hearst was interviewed by the British psychiatrist and expert on ‘brainwashing’ William Sargant, whose personal papers are housed in the Wellcome Library. Sargant's press cutting from People magazine, 1975.

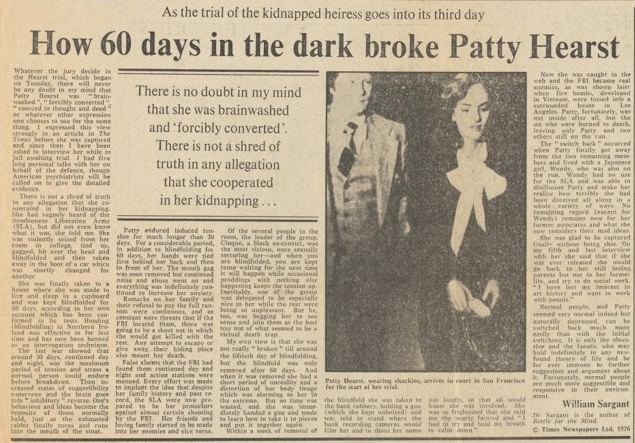

“There will never be any doubt in my mind that Patty Hearst was ‘brainwashed’, ‘forcibly converted’, ‘coerced in thought and deed’ or whatever other expression one chooses to use for the same thing.” An article by William Sargant for the Times newspaper, 1975.

GUILTY! How the verdict of Hearst's trial was reported on the cover of Newsweek, March 29, 1976.

The ‘brainwashing’ defence had no legal precedence and was not accepted by the jury. Hearst was sentenced to seven years in prison. Despite the similarities, ‘Stockholm Syndrome’ did not feature in public debates surrounding the trial, but it emerged in the American mass media following the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979 at the American embassy in Tehran. In a 1982-edited volume called ‘Victims of Terrorism’, several scholars applied the term Stockholm Syndrome retroactively to Hearst’s story. By the time Hearst received a full pardon from US President Bill Clinton in 2001, Stockholm Syndrome, rather than brainwashing, dominated psychological discussions of her case.

Studying the syndrome

By its nature, Stockholm Syndrome is difficult to study under controlled conditions. Remarkably, researchers from the Virginia Commonwealth University attempted an experiment in the early 1980s, simulating a hostage situation in which volunteer airline staff were taken hostage by FBI agents posing as terrorists and detained for four days. Researchers found that hostages who perceived the terrorists as friendly rather than aggressive could better adjust to captivity, and that hostages seen as friendly by their captors reported a more positive experience. The experiment legitimised Stockholm Syndrome behaviour not only as a normal response to captivity, but also a practical one.

Former captives known as ‘Chibok girls’ entertain guests in Abuja, Nigeria.

In 2017, over 80 Nigerian female students who had been kidnapped from the town of Chibok in 2014 were released by the militant Islamist group Boko Haram, and it was widely reported that one of the hostages had chosen to stay with her captors. Some former Boko Haram captives, not from Chibok, have spoken of the complex emotional and social ties they forged in captivity. Many married Boko Haram members and had formed complex emotional bonds. One former bride described feeling ostracised from their family and community and wanting to return to Boko Haram.

More than 40 years after Jan Erik-Olsson’s bank robbery, Stockholm Syndrome remains debated among psychologists. It is frequently described as an unconscious response to the trauma of captivity that can increase a victim’s chances of survival. Although the phenomenon remains rare, it has been applied to numerous cases of kidnapping and hostage situations around the globe. Former detainees have embraced the term to understand their own experiences, alongside brainwashing and post-traumatic stress disorder. In a recent documentary, David Hawkins, one of the 21 American POWs who chose to live in China in 1953, uses these labels to make sense of his own story.

Critics suggest that the term Stockholm Syndrome is still problematic. Like ‘brainwashing’, it remains ambiguous and fails to account for the unique circumstances encountered in each case. Nonetheless, the idea of Stockholm Syndrome remains resonant. It alerts us to the psychological impact of kidnapping and imprisonment and the mysteries of group dynamics. In captivity, isolated from our ordinary support systems, we may be vulnerable to feelings of culpability, rage, despair or even murderous destructiveness. Our identities may prove very precarious when our defences are down.

Find out more about the Hidden Persuaders project examining ‘brainwashing’ in the Cold War at Birkbeck, University of London. The War of Nerves, an exhibition about the psychological landscape of the Cold War runs at the Wende Museum in Los Angeles until January 2019.

About the contributors

Charlie Williams

Charlie Williams is a postdoctoral researcher working with the Hidden Persuaders project at Birkbeck, University of London. His research explores Cold War culture through the lens of the human sciences with an emphasis on the psychological, emotional and economic relationships between humans and emerging 'psy' technologies.

Sarah Marks

Sarah Marks is a historian of twentieth century science and medicine, and Central and Eastern Europe. She is a postdoctoral researcher with the Hidden Persuaders project at Birkbeck, University of London, and is co-editor of the book 'Psychiatry in Communist Europe' (with Mat Savelli, Palgrave, 2015).

Daniel Pick

Daniel Pick is professor of history at Birkbeck, a psychoanalyst at the British Psychoanalytical Society, and the senior investigator on the Wellcome-funded Hidden Persuaders project. His publications include 'Psychoanalysis: A Very Short Introduction' (OUP 2015) and 'The Pursuit of the Nazi Mind: Hitler, Hess and the Analysts' (OUP 2012)