When Chris North was born intersex in the 1940s, his family was encouraged to keep his condition secret. Here he describes his early childhood, during which, alongside the expected experiences of school, friends and family life, ran an unusual and unspoken parallel stream. Medical examinations and tests, painful operations and recovery periods. All without a word of explanation.

Born different

Words and artworks by Chris Northaverage reading time 4 minutes

- Serial

After most births, parents celebrate the news that they have a girl or a boy. When I was born in 1946 into a strict but loving working-class religious family in the south of England, there was no such celebration. I was neither boy nor girl: I was sex unknown.

Initially, doctors thought I had scrotal hypospadias: a non-joining of the scrotum with a cleft between my legs. It was not until I was 13 that I was finally identified as a “true hermaphrodite” or ovotestis intersex. My parents must have felt bewilderment and disbelief.

Intersex people have physical sex characteristics which don’t conform to the typical medical and social norms of binary male and female bodies, including chromosomes, genitals, gonads, hormones and other reproductive anatomy. I didn’t find out how this related to me until my early twenties.

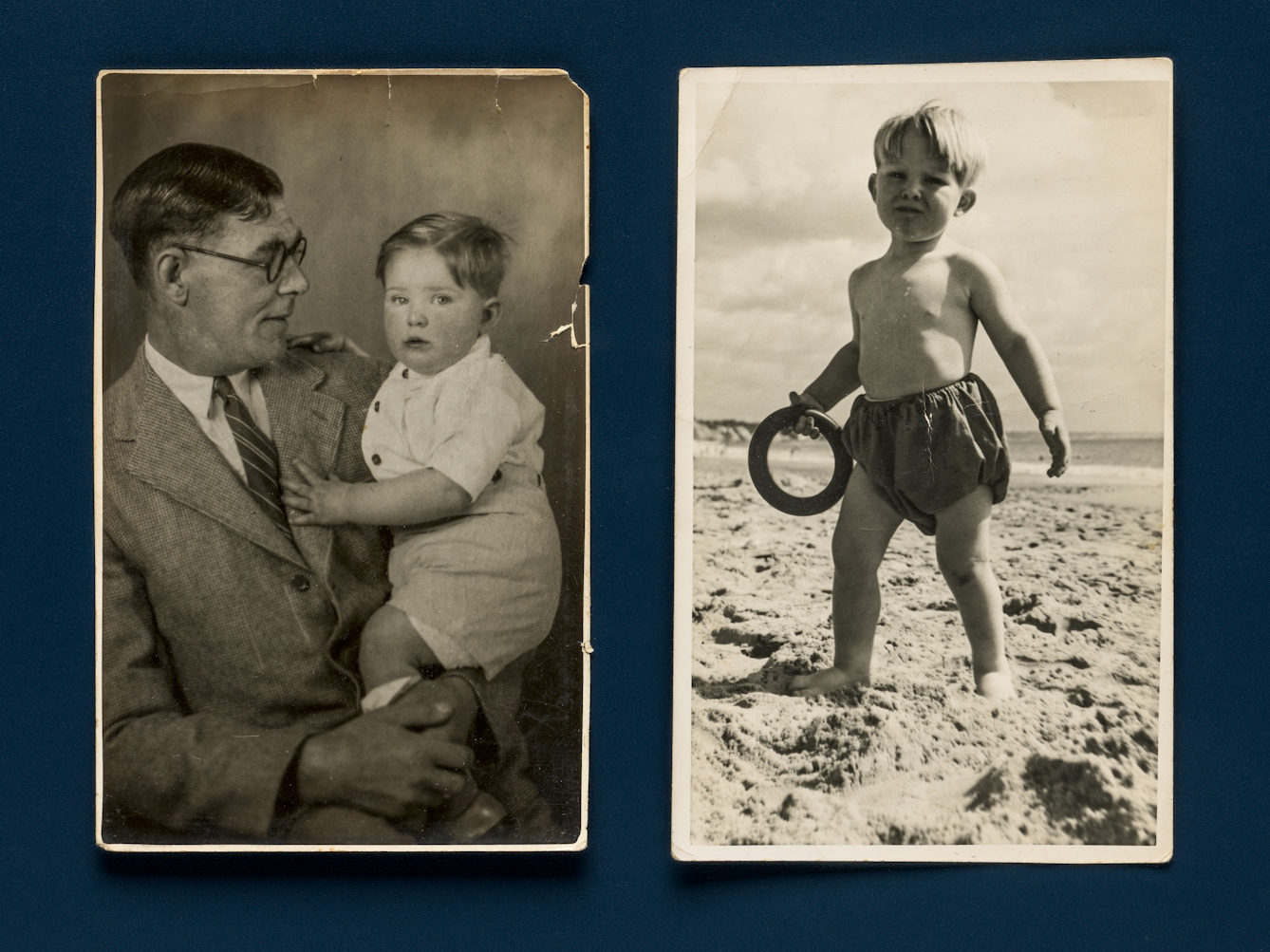

Despite these inner differences, in many ways my childhood probably had many similarities with others born seventy years ago. I spent time happily playing imaginary games with friends outdoors, enjoyed memorable family holidays to Bournemouth with paddling and ice creams, and made things out of wood or with batteries, bulbs and motors. I wrote mythical tales and went on outings with my older sister.

Unlike most other children, alongside this childhood ran a life of relentless and inescapable hospital visits and surgeries.

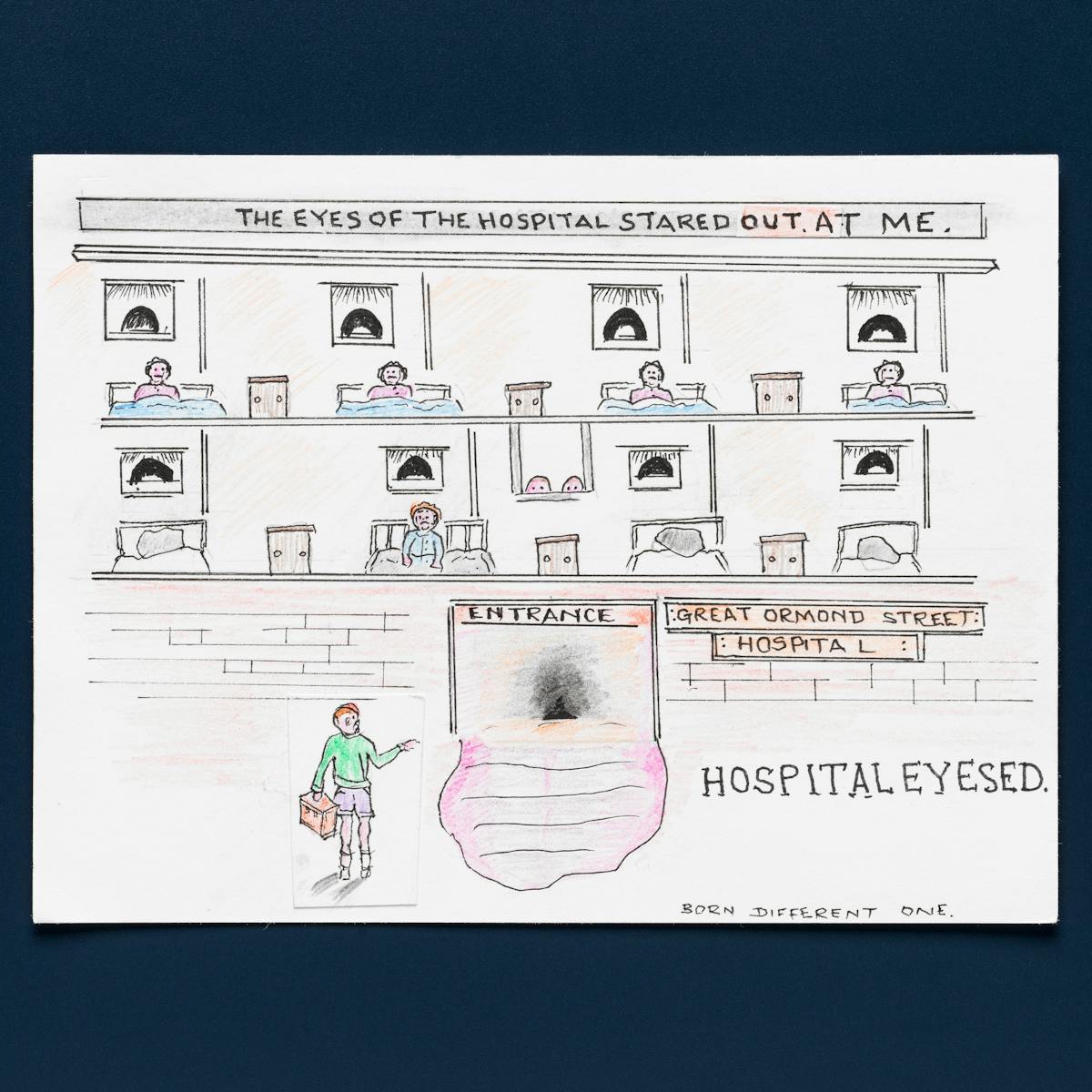

'Why have you abandoned me?' by Chris North, 2023.

Intrusive examinations and painful surgeries

Even before I arrived in hospital, I would feel terrified. It was usually on our way to chapel that my dad would tell me of an impending trip to hospital. I would kneel by my bedside at night and pray to Jesus it wouldn’t happen, but no intervention came and I would find myself on the train from Reading to London soon afterward. On arrival, the eye-like windows of the hospital stared down at me.

In the 1950s, there wasn’t so much awareness of attachment theories and the impact on a small child of being left without family in an alien environment. From a very young age, I found myself seemingly abandoned at Great Ormond Street Hospital for Sick Children, London. I was only able to see my family for a short time on a Saturday.

During my hospital stays, I was surrounded by unknown adults doing painful things to me without any explanation. Probing, cutting, stitching.

'Keep your secret' by Chris North, 2023.

I still recall being about three, tied with bandages by my wrists and ankles to the hospital bed to prevent me touching the stitches between my legs or tugging on the catheter tube. A rectal examination by a male doctor with a rubber, Vaseline-covered finger prodding painfully and unexplained up my back passage.

I also remember being taken to an examination room. My lower half was stripped naked, then photographed for my medical records. The lens of the camera was like the eye of a voyeur gazing at me.

I spent much of my time wondering what was going to happen to me next.

Nobody asked me how I was feeling. My body was looked over, but my psychological self was overlooked.

Left: Chris with his dad, aged two. Right: Chris on Bournemouth beach, aged three and a half.

A closely guarded secret

Of all the information and news of surgeries that we received, the most significant message doctors gave my parents, with serious repercussions, was, “Christopher’s life must forever remain a secret.” My aunts and uncles were oblivious to what I was going through. The reason for the surgeries I underwent, the intimate examinations, and the feelings of being different, remained a secret to me too.

Although my parents felt unable to explain why all this hurt and misery was happening to me, I knew they loved me. When I had blood tests, I saw tearful distress in Dad’s eyes. He encouraged me with various hobbies, and we went out on long tandem rides together. Dad built me a bike.

When I was eight, pedalling down a path, my foot slipped and I came crashing down, painfully hitting my ‘scrotum’ and repaired urethra. When I went to wee, I was horrified to see a leak of urine between my legs. I couldn’t tell anyone and face more surgery; it became a secret. From then on, I squatted on the toilet like a girl.

Mum loved me, but she was emotionally cold. She suffered from frequent bouts of nausea, vomiting and migraines. I never remember her kissing or cuddling me. When I was nine, she sought to end her life and was taken away for a while. I felt abandoned again. My older sister by nine years became a second mother to me.

It was during adolescence and the onset of puberty that the many ways in which I was different from my peers became really apparent to me. I didn’t begin changing in the same way as them and I faced various kinds of exclusion.

About the author

Chris North

Chris North is an author, independent scholar, creative arts facilitator, intersex advocate and activist. He’s been a teacher, social and community worker and is now a storyteller. He shares his powerful personal experience to provide much-needed “lived historical intersex testimony” and works hard for other minorities and those marginalised by society.