The human love of alcohol – although not of its most destructive effects – has a long history, and we’ve always found ways round efforts to ban or control consumption. But after 9,000 years, there are signs that booze might finally be getting a little boring.

Booze and bad behaviour

Words by Stevyn Colganaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Serial

In 2009, Dr David Nutt, former chair of the UK government’s Drugs Advisory Committee, published a report in which he ranked 20 drugs based upon their negative effects on both users and society. Tobacco and cocaine were described as being equally harmful, while ecstasy and LSD were listed among the least damaging. Most controversially, alcohol was reported to be more dangerous than heroin. And there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that he may well be right.

In 2016 (the latest UK figures I could verify at time of writing) alcohol-related violent crime accounted for around a quarter of the 1.2 million offences of violence recorded by the police (and, undoubtedly, many more that went unreported) and there were 7,327 alcohol-specific recorded deaths. By comparison, there were 3,744 deaths involving the use of both legal and illegal drugs (of which 69 per cent were misuse deaths), although it must be noted that heroin and alcohol are not equally easy to obtain.

David Nutt was famously sacked after disagreeing with the government’s decision to reclassify cannabis as a restricted drug. He argued that alcohol consumption would drop by 25 per cent if we legalised cannabis and that the cost of policing cannabis use was only £500 million a year compared with the £6-billion-a-year bill for policing the use of alcohol.

And yet the purchase and consumption – and, to some degree, the production – of alcoholic liquor is entirely legal.

Humans have been producing alcohol in various ways and in various places for centuries. This illustration from the Ming period (1368–1644) shows the manufacturing of Magu liquor and Huai'an mung bean liquor.

Nine thousand years of getting drunk

Our relationship with alcohol goes back a very long way. Evidence has been found of fermented drinks being produced in China in 7000–6650 BCE. The ancient Egyptians had alcoholic beverages, as did the Aztecs and the Celtic tribes. For the Greeks and Romans alcohol was a staple of everyday life.

By the 16th century the amount of beer consumed by the average Briton was about 17 pints per person per week, although it was only 1 per cent alcohol, compared to 3–4 per cent today. And, at the height of what became known as the ‘Gin Craze’ in the mid-18th century, over 18 million gallons of spirits were being drunk per year by a national population of just 6.25 million people: that’s nearly three gallons (ten litres) per person (from J. Doxat, ‘The World of Drinks and Drinking’, pp. 98–100).

Today, more than 35 billion gallons (133 billion litres) of alcoholic drink are sold worldwide per year.

Why do we drink?

There’s no escaping the fact that we like a drop of the hard stuff. But there’s no one simple answer to the question, ‘Why?’

It’s not just for the ‘hit’; there are many other forms of intoxicant, legal or illegal, that can provide a bigger or faster high, and the effects of alcohol consumption are cumulative rather than immediate. And it’s not just for the taste, either; some drinks take a great deal of getting used to before we enjoy them. We have to ‘learn’ to like them, and it is usually societal or peer pressure that first prompts us to try.

But that, perhaps, is the key to understanding our relationship with alcohol; only a small percentage of people drink solely for the purpose of becoming intoxicated. The rest of us drink because it’s a shared social experience, or because it makes us feel relaxed and lowers our inhibitions. It makes us feel happy because ethanol, the main alcoholic component of most drinks, increases the release of dopamine. And, for most of us, that’s enough.

MORE: Read about how alcohol and opiates used to ‘soothe’ the nation’s children

However, like all intoxicants, there is a sliding scale that goes from pleasurable high to destructive obsession and addiction, a tipping point beyond which lowered inhibition becomes risk-taking behaviour and the anaesthetic effect can quickly become a dangerous loss of physical coordination and cognitive function. This can result in our doing things we shouldn’t do, or saying things best left unsaid.

When I was a police officer I met any number of drunk people who had done or said things that they shouldn’t: like the man who climbed up a construction crane as a dare and was too terrified to climb back down; or the young woman who rode a shopping trolley down a hill and through the window of a chemist; or the chap who dramatically ended his marriage by mistaking a cupboard for the en suite bathroom door and subsequently urinating on his wife’s wedding dress; or even the minor celebrity that I once caught climbing over the wall of a convent while apparently ‘on a mission to cure the nuns’.

Most damagingly, the pleasurable ‘hit’ we get from the release of dopamine can lead us to want more and more. That’s when addiction replaces pleasure.

Anti-alcohol advertising

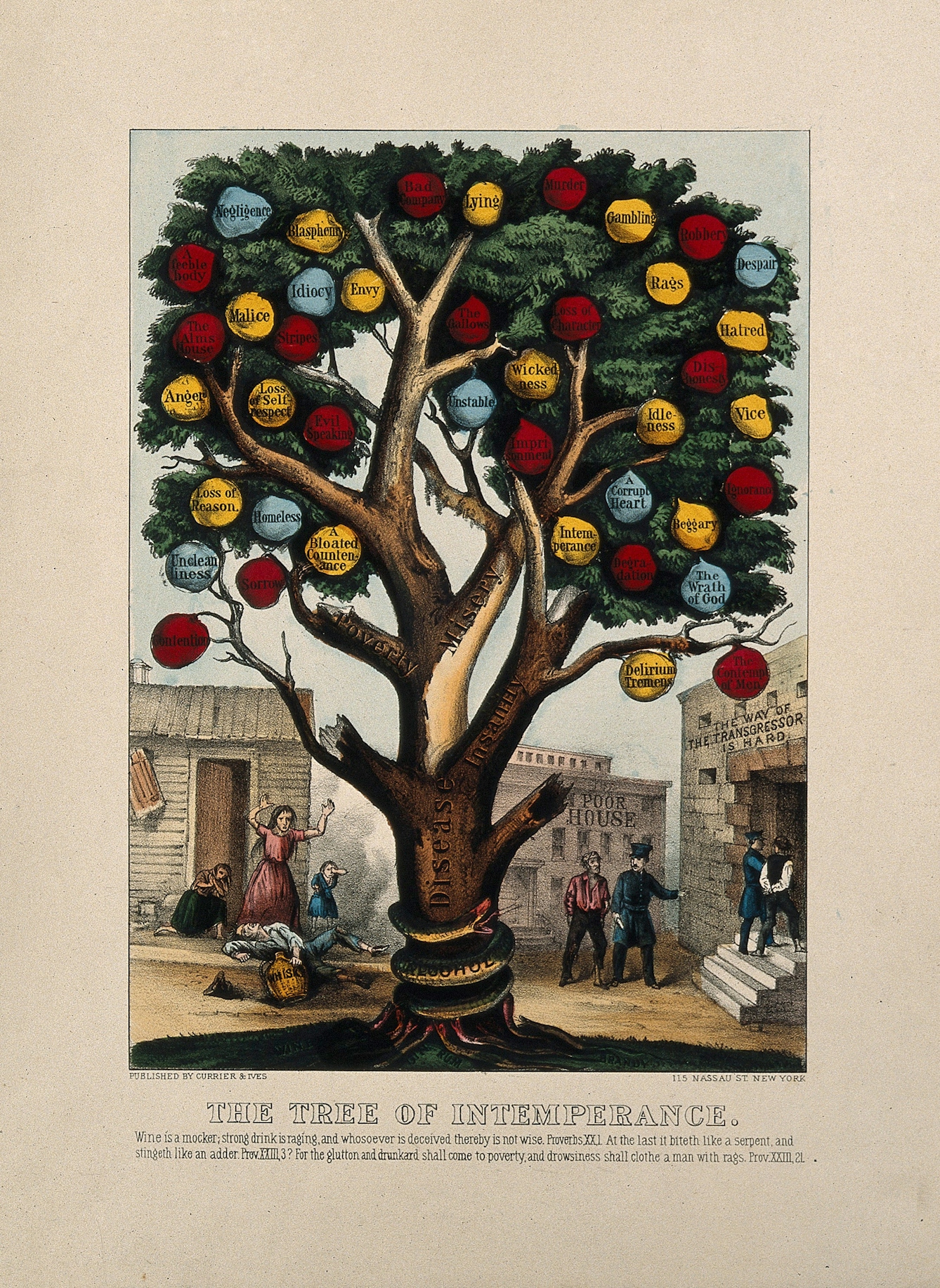

This allegorical print from the 1800s was designed to put people off alcohol by showing its ill effects. The trunk of the tree is inscribed “Disease”, a left branch “Poverty”, the lower right branch “Insanity”, and the upper right branch “Misery”. The building on the left is labelled “Poor House” and there is a prison on the right.

This poster from 1911 was likely produced for the International Congress Against Alcoholism held in The Hague that year. This was the year when temperance organisations around the world were at their peak.

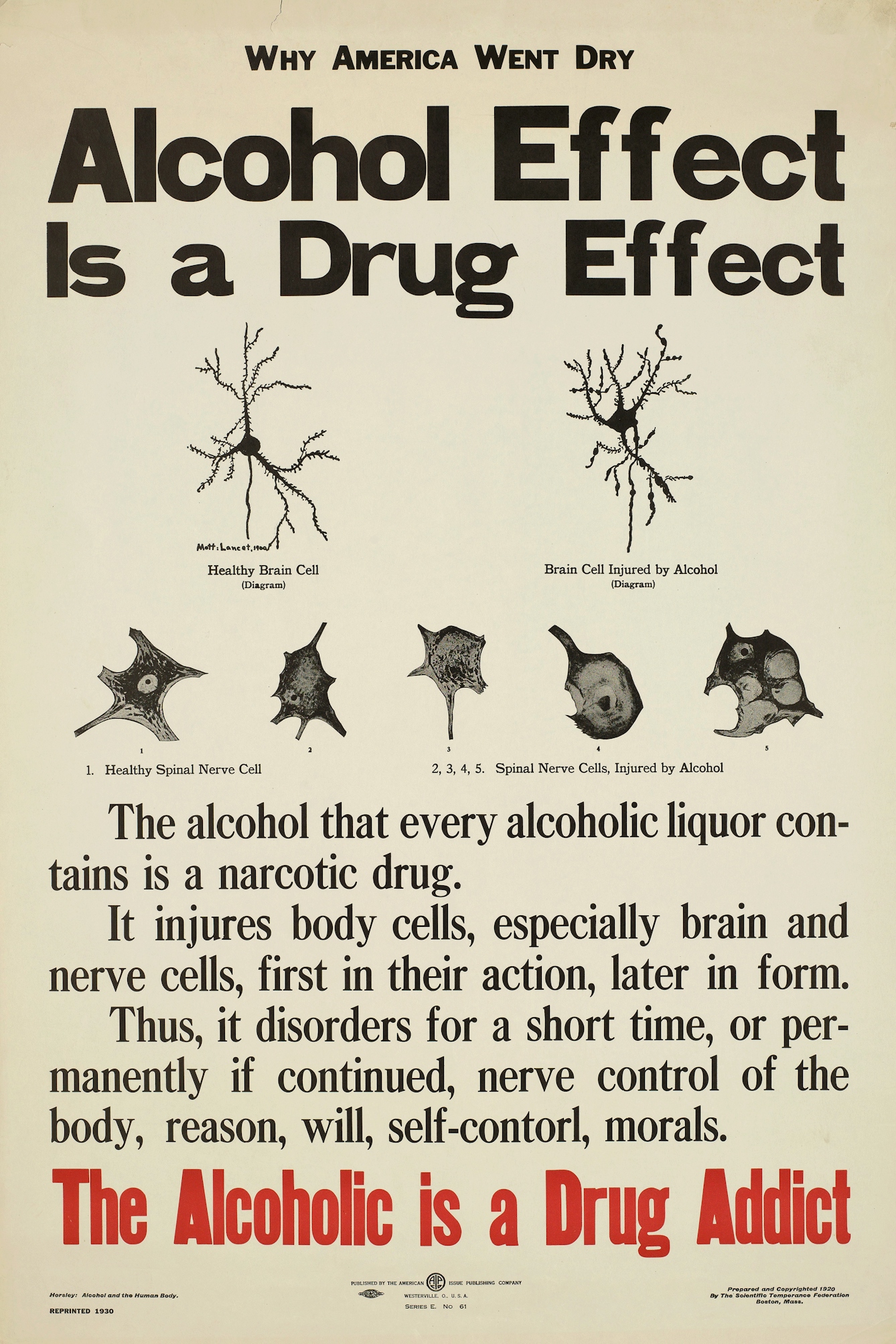

In the 1920s, prohibition in the United States banned the production, importation, transportation and sale of alcoholic beverages. The Scientific Temperance Federation of Boston produced this poster to try and persuade people not to drink.

Booze bans and alternatives to alcohol

So how do we reduce the negative effects of alcohol consumption? There have been attempts to legislate against it and many countries have, at some time, attempted to introduce prohibition. However, alcohol is easily produced and making it illegal simply drives production and consumption underground. This invariably affects the quality and safety of the product and allows criminal elements to take control of manufacture.

Meanwhile, many other intoxicants are controlled rather than banned, and their production, sale and chemical content are regulated. Included amongst these items are solvent-based products and some things that we rarely think of as intoxicants, such as caffeine and nicotine. So perhaps one possibility could lie in better regulation of alcohol production and sale.

Another is replacing alcohol with a safer, non-addictive alternative while retaining the social aspect of it, as suggested by David Nutt in his 2012 book ‘Drugs – Without the Hot Air: Minimising the Harms of Legal and Illegal Drugs’. Dr Nutt has isolated a group of chemicals that could be used as a replacement and, in time, he plans to release a range a non-alcoholic drinks that give you the all the effects of alcohol but without the negative results, such as hangovers.

“The intoxicating effect of the first three ‘doses’ will be cumulative,” he says. “But subsequent shots will have no effect.” Once you reach a certain plateau of ‘drunkenness’, you stay there. He points out that drinks companies will need to be persuaded that it is safe. “Their product kills [almost] 3 million people a year. They would like a safer alcohol, but… we need to incentivise them to change. What we need is for the public to say ‘we need this’, and for governments to encourage it as a healthy substitute. The tobacco industry eventually came to accept the worth of electronic cigarettes. The alcohol industry will come to accept that an alcohol substitute has a place too.”

This 1559 woodcut image from Frankfurt shows that bad behaviours have been associated with drinking in many places for hundreds of years.

Sober thoughts

Social anthropologist Kate Fox takes a slightly different view. In a series of carefully controlled experiments, she gave people placebos and found that the subjects exhibited the same kinds of behaviours that they’d have displayed if they’d been given alcohol. As she told BBC Radio 4’s ‘Four Thought’ programme: “To put it very simply, when people think they are drinking alcohol, they behave according to their cultural beliefs about the behavioural effects of alcohol."

She points out that there are plenty of other societies and cultures – many of which drink far more than we do in the UK – where drinking is not associated with bad behaviours. We’re not even in the Top 10 nations of boozers. According to the World Health Organisation, Belarus, Andorra and Lithuania top the chart: the Belarus average is 14.4 litres, while the UK average is around 10.3.

Fox has conducted further experiments that appear to support her assertion. “Even when people are very drunk, if they are given an incentive – either financial reward or even just social approval – they are perfectly capable of remaining in complete control [and] behaving as though they were totally sober,” she says. “Alcohol education will have achieved its ultimate goal, not when young people in this country are afraid of alcohol and avoid it because it is toxic and dangerous, but when they are, frankly, just a little bit bored by it.”

And she might be right. Recent figures show that drinking among young people is in decline and a 2017 report by the Office of National Statistics suggests that more than a quarter of 16 to 24-year-olds are teetotal, with just one in ten seeing drinking as ‘cool’. As Hannah Jane Parkinson wrote in a recent feature for the Guardian: “Drinking is ingrained in our social life – much as cigarettes were until public-health campaigns led to a huge cultural shift. With many young people eschewing alcohol, the beginning of the end of booze Britain is in sight.’

Time will tell.

About the author

Stevyn Colgan

Stevyn Colgan is an author whose debut novel, 'A Murder to Die For', was shortlisted for the Penguin Books’ Dead Good Readers’ Awards. For more than a decade he was one of the ‘elves’ that research and write the TV series 'QI', and he was part of the writing team that won the Rose d’Or for BBC Radio 4’s 'The Museum of Curiosity'. In his previous career he was a police officer in London for 30 years.