One of our most common condiments was once very valuable and, until surprisingly recently, used as a versatile medicine.

Black pepper to fuel fiery fights and cure haemorrhoids

Words by Alice White

- Story

Since ancient Greek and Roman times, pepper has been prized for its ability to balance the humours of the body. It was so highly valued that, in 408 CE, Visigoth King Alaric I took 3,000 pounds of pepper as a ransom payment from the Romans in exchange for not attacking Rome.

It’s not surprising that this versatile spice was so highly valued, considering the many ways it was believed to improve health. A 1745 text tells us that the condiment can “attenuate the gross and viscous Humours, help Digestion, create an Appetite, expel Wind, resist the Malignity of the Humours, provoke Sneezing, and excite Seed”.

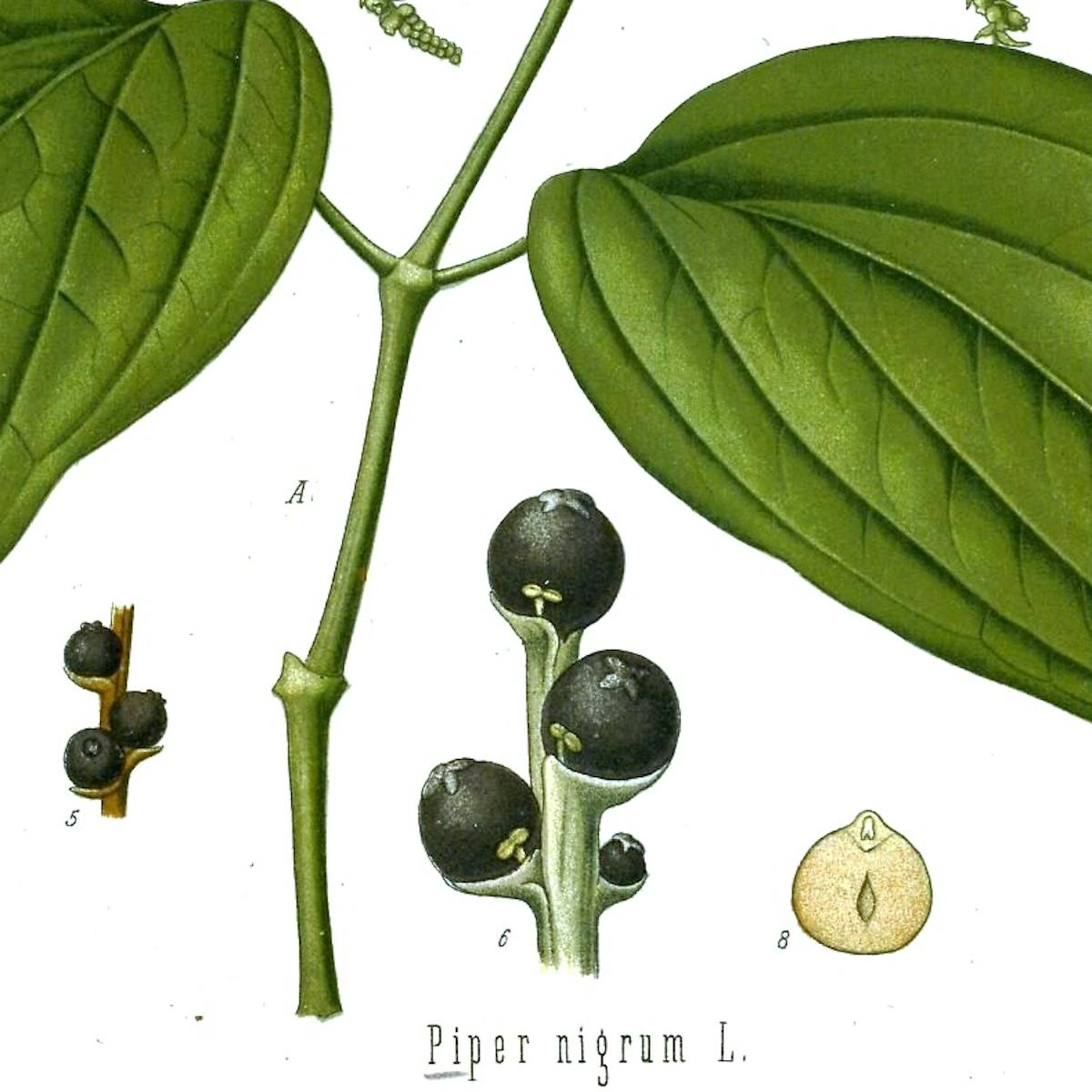

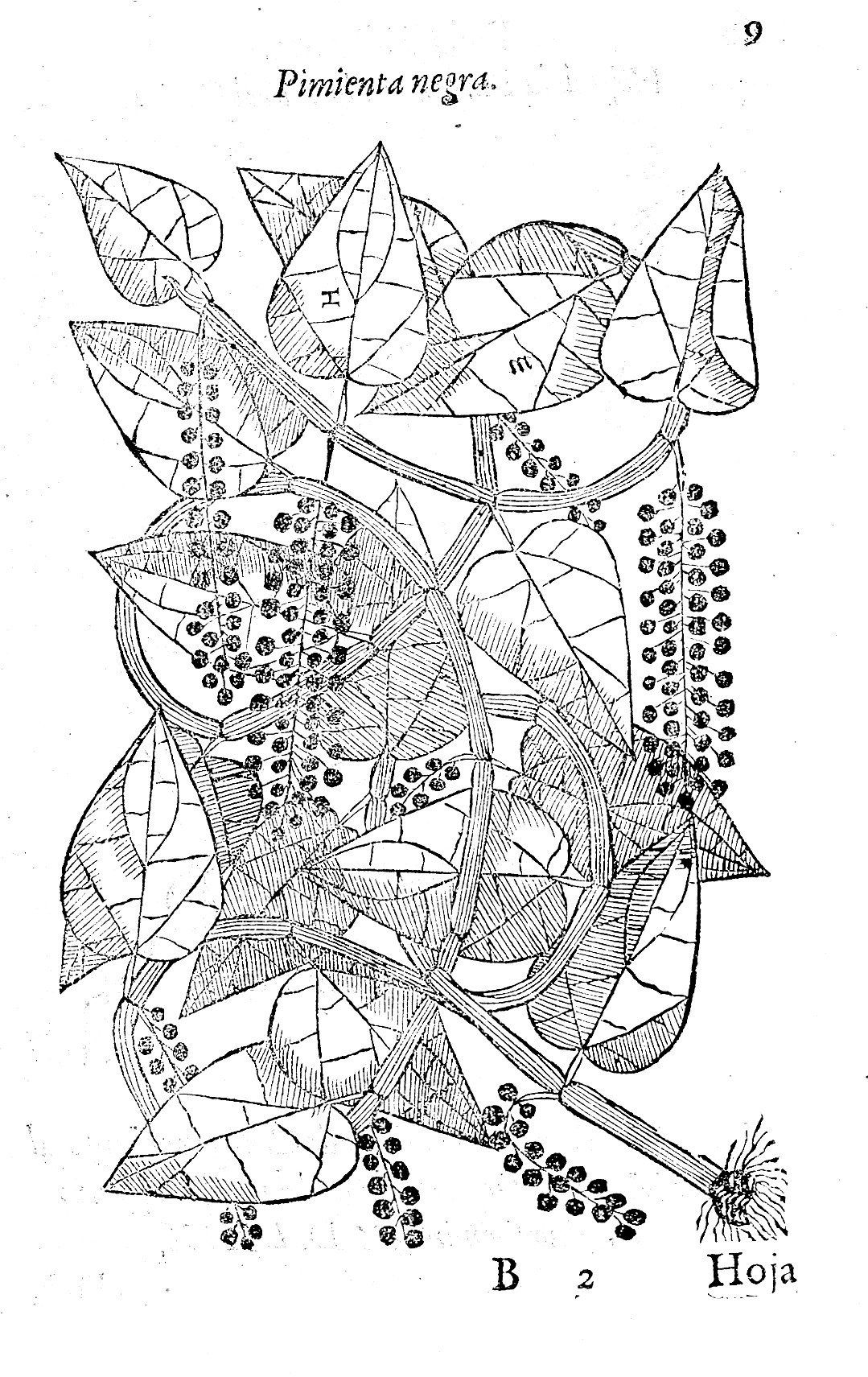

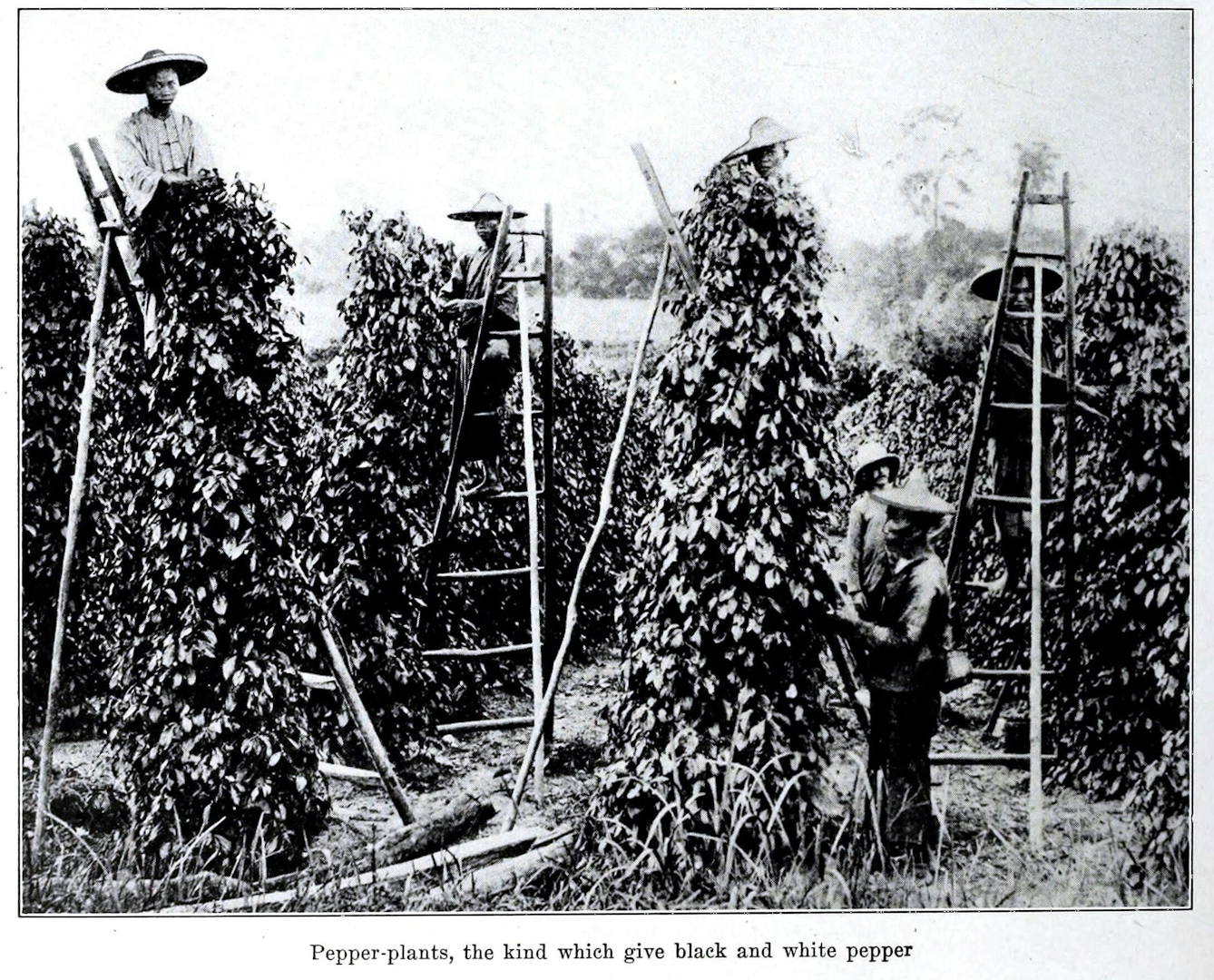

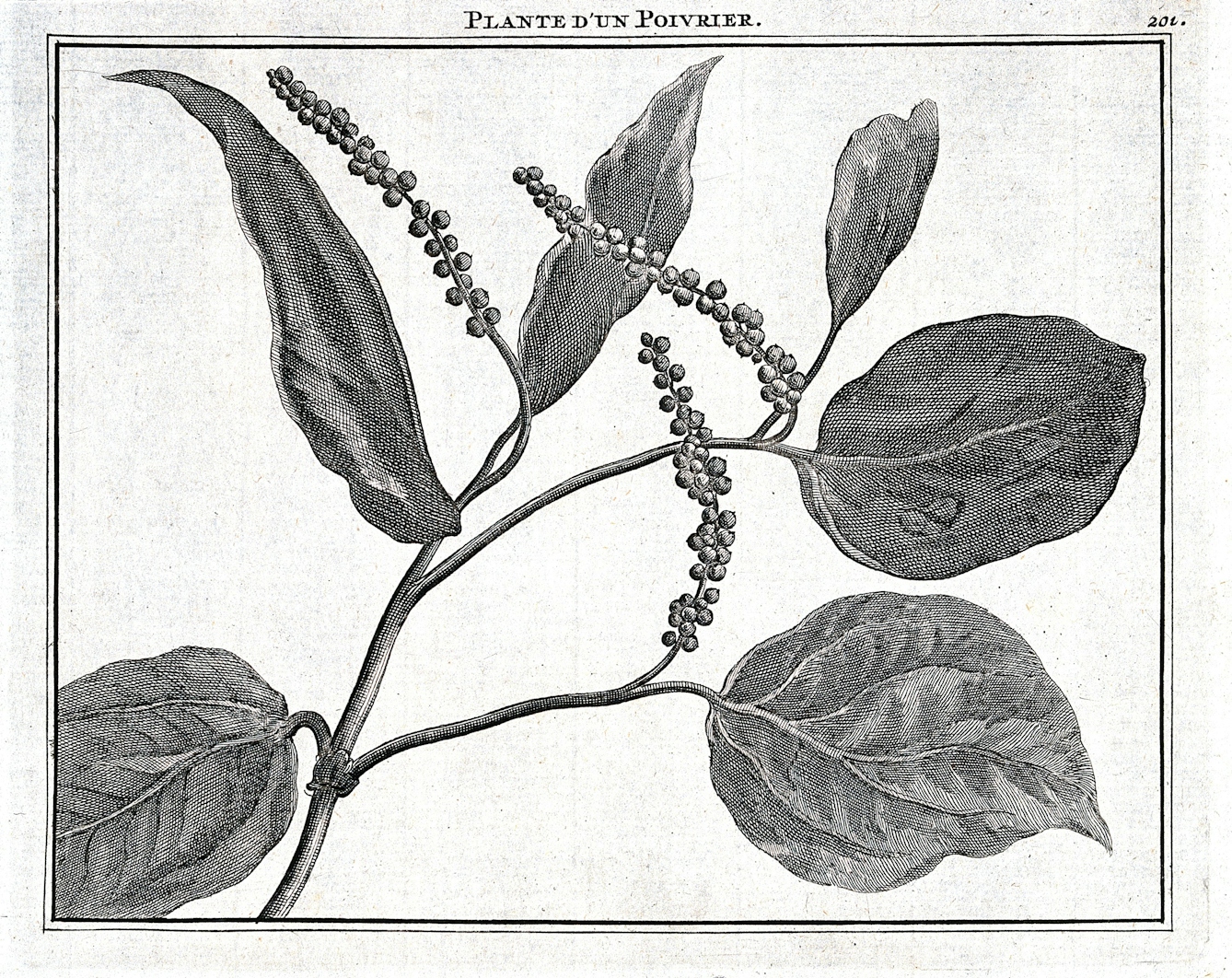

Pepper plants

One of the earliest Western depictions of the black pepper plant, this woodcut appeared in Cristóbal Acosta's bestselling book on drugs and medicines (1578).

This Chinese painting of pepper (hujiao) is done in the meticulous (gongbi) style, in colour on silk, from 'Bencao tupu' (1644).

This photograph of people collecting pepper appeared in a 1923 guide for grocers.

If you fancied a big juicy steak, this was heavily sanguine (linked with the blood, moist) – according to humoral theory, you could balance out your steak by adding some hot, dry pepper. As a man, you’d especially want to avoid an excess of moisture in your body, as this was associated with women’s bodies and believed to be a common cause of impotence.

Pepper’s ‘manly’ spiciness also led to it being associated with fighting words. In Shakespeare’s ‘Twelfth Night’, for example, Sir Andrew receives a document and declares “there’s vinegar and pepper in’t”. Pepper also appears in a 1680 battle of the quacks. Robert Bateman published a pamphlet blasting his rival and “ignorant scribbler” Blagrave, who he thought was pirating his scurvy grass “miracle-cure” – he accused Blagrave of not even knowing his pepper, saying:

This engraving from 1737 featured in a French book on ‘Travels into Muscovy, Persia, and the East Indies’.

Are not many things brisk and piquant to the taste of contrary qualities in operation; Sure this learned Travelling Mountebank, though apt to take pepper in the Nose, was never thoroughly acquainted with it, else he might know, that though it be hot on the palate, ’tis cold in the stomach.

Bateman was hinting that Blagrave was the opposite of what he appeared: he might be hot in the mouth (and talk a good talk) but that he had a cold (feminine, weak) stomach – the historic equivalent of being all mouth and no trousers. Bateman presented his enemy as the opposite of Elizabeth I, who claimed to have “the stomach of a king” in her famous Tilbury speech of 1588.

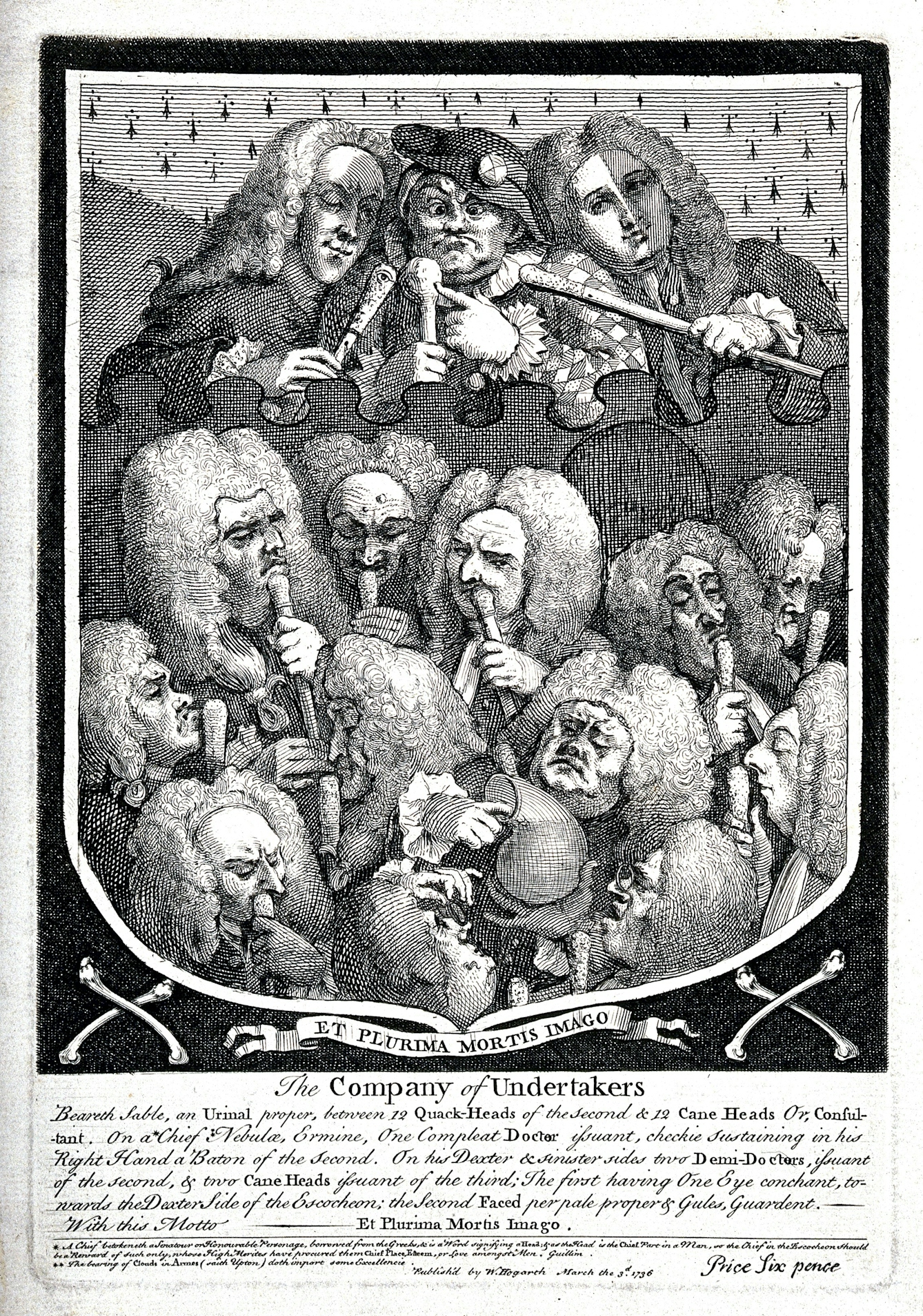

Hogarth caricatured physicians and quacks (including Joshua Ward) in his engraving of 1736, presenting them as undertakers as a criticism of their lack of ability to heal people.

Healing haemorrhoids

One 17th-century man who did know his pepper was Joshua Ward. Ward is best known today for inventing Friar’s Balsam, which is used to treat wounds, but he is also credited with inventing Ward’s paste. The paste was mostly made of black pepper, which was mixed with elecampane and fennel.

It was used to treat haemorrhoids, and the recommended dose (as described in an 1835 journal) was a piece the size of a nutmeg to be taken thrice daily. The journal suggested that even with this basic peppery concoction, medical expertise was essential. One doctor related how a foolish patient had “indiscreetly taken an immense quantity of Ward’s paste” and his colon was “found quite full of it after death”.

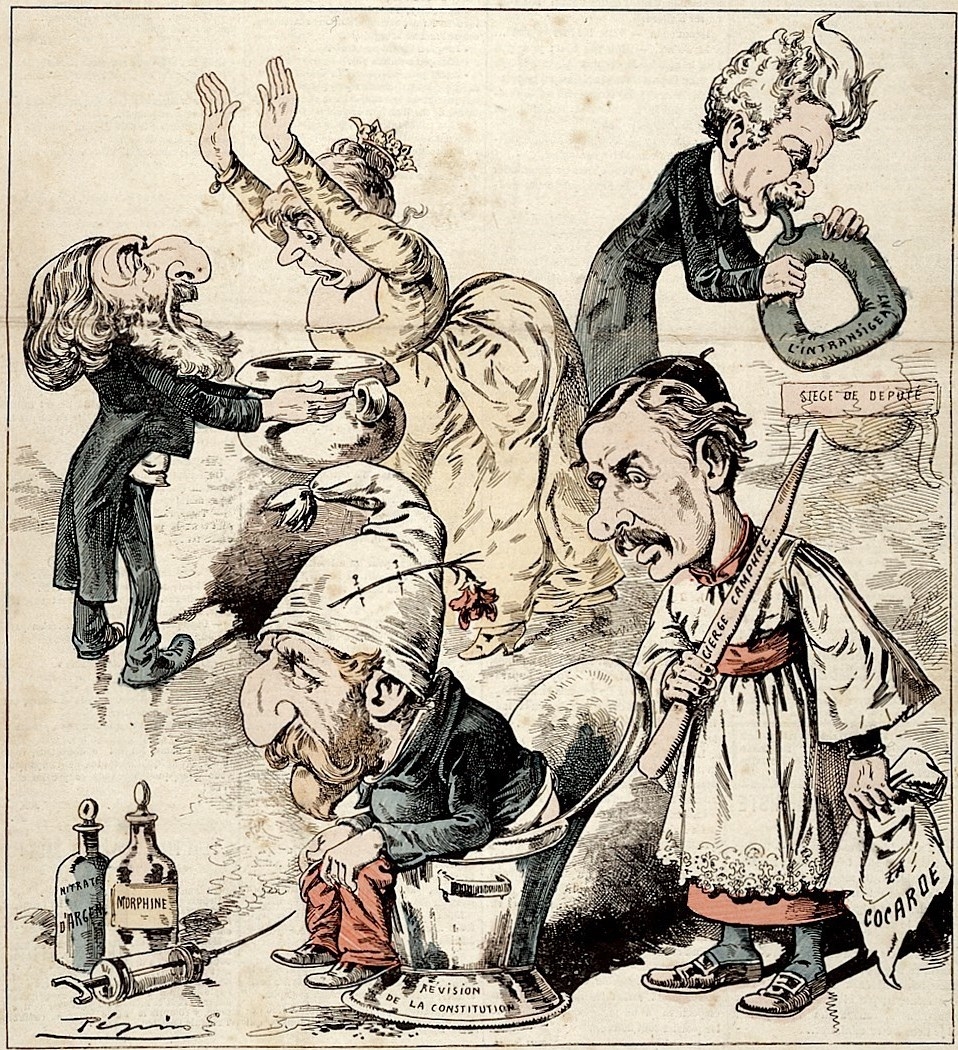

Haemorrhoids were a laughing matter for French caricaturist Pépin, who mocked the Parti National by depicting them as having many pains in their behinds.

Another patient “little thinking that something put into the stomach was to cure disease in the rectum, crammed as much as he could bear of it up the rectum”. This patient had a somewhat happier outcome, though: “I dare say it gave him a great deal of inconvenience, but… it cured him.”

Wellcome tabloids came in many varieties, including one that featured piperine, the substance derived from black pepper.

The Bishop of Durham, Thomas Thurlow, desperately resorted to Ward’s paste in 1791, as it had cured him of haemorrhoids in the past. Sadly for the bishop, this time his doctor John Hunter had also found a large incurable tumour, from which the paste could not save him. Hunter liked to keep medical specimens, and so today, the bishop’s rectum resides at the Hunterian Museum.

Black pepper continued to be used for piles, and even for intermittent fever, ague and gonorrhoea, right into the 20th century. Henry Wellcome produced one of his famed ‘tabloids’ (what we'd call tablets or pills today) incorporating piperine (the crystallised alkaloid derived from pepper), which was recommended for “dyspepsia and flatulence” and also, 200 years after the invention of Ward’s paste, “in the treatment of haemorrhoids”.

About the author

Alice White

Alice is a digital editor and Wikimedian for Wellcome Collection. Before joining Wellcome, she researched frogs, moustaches, psychiatry in World War II, and British science-fiction fans.