What parents keep to trigger memories of their baby’s early days ranges from photos and christening gowns to medical paraphernalia and placentas. With recent thoughts of her son’s difficult birth in mind, Erin Beeston explores her family’s 19th- and 20th-century baby keepsakes.

“Something for the memory box,” said the midwife as she handed over my baby’s ECG pads, a device that measure the electrical activity generated by the heart as it contracts, wires hanging from plastic circles decorated with animals and teddy-bear illustrations.

The ‘memory box’ is a common and curious feature of our material lives, made to collect keepsakes, to ignite reminiscence. Baby memory boxes are a unique form of collecting that I have found to be charged with emotion, whether that’s collecting objects related to my own children or rediscovering my family’s treasures.

In my experience, collecting for the memory box was an active impulse rather than a retrospective decision – an urge to save the precious memory of my child’s first hours, encouraged by healthcare professionals.

Alongside strong maternal emotions, recollecting birthing also brings distress and trauma; I certainly did not expect to bring my son home with medical paraphernalia other than his hospital wristband. I still feel lucky that my baby spent just three days in neonatal intensive care, only needing observation.

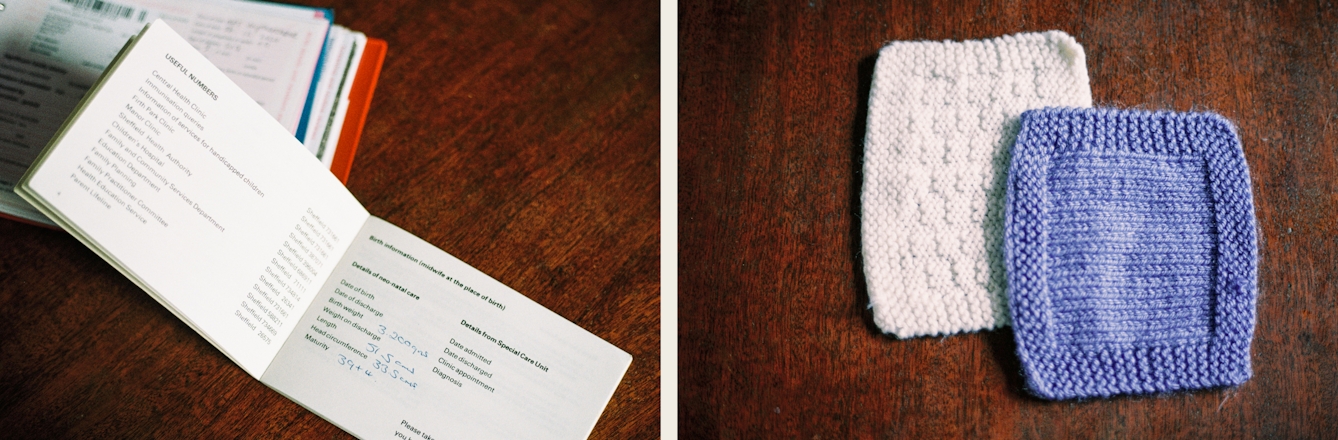

Unexpected hospital memorabilia given “for the memory box”. On the left, a neonatal blood-pressure cuff, and on the right, ECG wires and electrodes.

Other objects I gathered over our few days in hospital included his first photograph, taken by a nurse. This is hard to look at now, a reminder that unlike my older boy, I could not hold him and enjoy a messy first photograph on the labour ward. The wires and tubes visible in the picture make his fresh newborn body seem especially vulnerable.

I also kept our comfort squares – a pair of knitted squares that I swapped between dressing-gown pockets and my boy’s incubator, so we had each other's scent. A beautifully simple gesture with an underlying use – apparently keeping this close helps with bonding and milk supply. I was touched by these kinds of objects, often thinking of the parents of ill or premature babies whose lives revolved around ward visits and care given through glass.

With these memories fresh, I returned to boxes and albums of my family's babies and uncovered various keepsakes. You may encounter similar, sometimes surprising, upsetting or even shocking objects; here is how I felt about objects imbued with the precarity of birth.

Erin’s baby record book from the 1980s in front of her own son's modern “red book”, alongside the knitted comfort squares Erin and her son shared during his time in the incubator.

Brief lives remembered

Among my grandmother’s treasured objects, I discovered the baptism certificate of my late father, John, born prematurely on 5 August 1951 at the Jessop Hospital for Women, Sheffield. My grandmother, Doris, suffered multiple miscarriages and stillbirths – I remember her quietly confiding in me about these when I was around 12.

John was baptised in his incubator aged just 11 days. I remember the story well, along with details of how prematurity accounted for his poor vision and his deep-set eyes. Viewing the document took me by surprise – I still found it upsetting despite knowing the positive outcome of the hospital stay.

I noticed the term “clinically baptised” on the certificate, a reminder that a conventional christening in church was deferred. It is common practice for Christians to baptise ill babies, ready to be received by God. I instantly felt empathy with my grandmother; how frightening it must have been baptising her infant, who survived childbirth only to be presumed unlikely to live.

On the final page of the album, following photographs taken in studios of mostly men in formal attire, I was surprised to encounter the unmistakable sight of a lifeless baby.

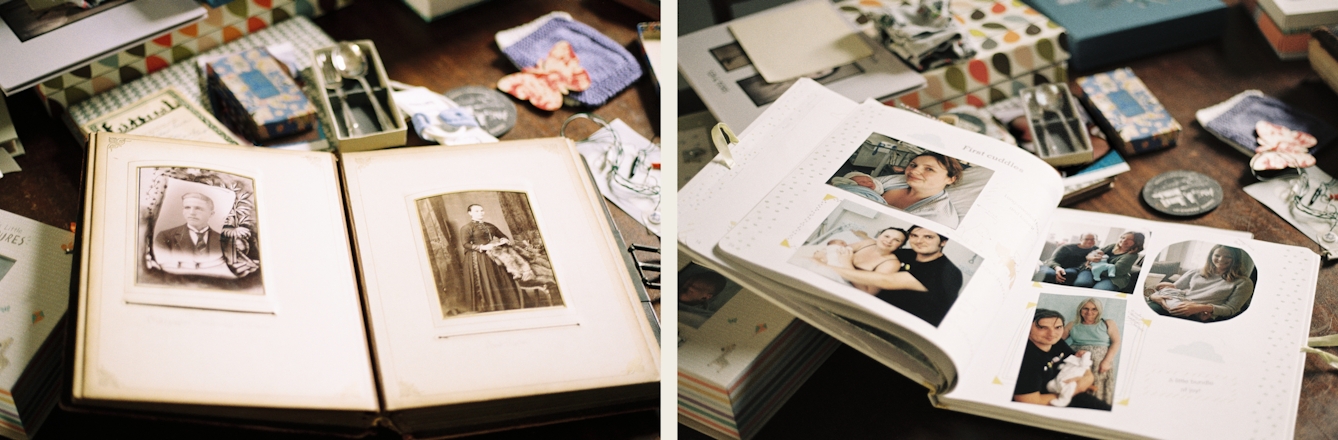

Treasured photograph album belonging to Erin’s ancestor Nathan Taylor, who carried it with him when he emigrated to America, alongside Erin’s own family scrapbook showing her eldest son's first moments in hospital.

My mother’s family also left mementos, from christening gowns to a grand family album of Victorian ancestors. On the final page of the album, following photographs taken in studios of mostly men in formal attire, I was surprised to encounter the unmistakable sight of a lifeless baby. Two photographs: one close-up of the baby lying limp against a white sheet, another with the child on her mother’s knee.

The mother is wearing a buttoned, dark-coloured dress, her face grave. The baby is held in her arms, like a living infant, but the stiffness and the eyes betray the reality of the image. Post-mortem photographs were adopted in the 19th century, following on from the Memento mori (meaning ‘remember that you must die’) cultural tradition.

Here, a professional photographer from Oldbury, West Midlands, has captured their images. With some help from my mother, we discover that this is Lucrecia, born on 14 April 1895 and dying on 6 June 1895. It was her younger brother, Joseph, who later recorded her birth and curated the photographs in the album.

Silver spoons and pickled placentas

Objects from my own birth remind me very strongly of place. My mother kept a slim, soft-cover baby-record book containing details of medical appointments, its silver cover depicting toddlers playing. This now seems scant in detail compared to the thick, NHS-issue red books I have for my sons.

Erin with her son in the bedroom, standing in front of a wardrobe bursting with memory boxes and old clothes.

Along with the book are a silver-coloured fork and spoon – not the prestigious variety, rather stainless-steel cutlery given by Jessop’s Hospital on the day I was born. Certainly less medicalised objects than those offered to me in 2020, these were given as mementos of being born in Sheffield – the steel city – on New Year’s Day. Viewing these objects also remind me of my mother’s story – thick snow, a long labour, and a forceps delivery at Jessop’s.

As well as objects like clothes, photographs and documents, some of the stranger items parents (including myself) have kept include physical material from the birth or baby. It is not uncommon to find pickled placentas; a close friend even discovered a foetus her grandmother kept in a jar.

I have kept umbilical cords, mainly because I feel uneasy disposing of a physical part of pregnancy. Given the poor condition they are in, I may change my mind. This quandary – of what to do with the cords (which fall off naturally after a few days) – reflects the emotions of memory boxes more generally: how can we keep a tangible sense of this fleeting moment? It also raises ethical questions on how we keep human remains, especially when one day these may become the possessions of an unsuspecting descendant.

Since the traumatic delivery of my younger son, I find baby memory boxes particularly powerful. The process of curating his box allowed me to address the birth in an intimate and methodical way, which helped to allay distressing memories. Birth and baby boxes represent an eclectic mix of bodily material, handmade items, visual records and medical objects. These objects evoke emotions and signify a time when life and death are immeasurably close, when love and fear abound.

About the contributors

Erin Beeston

Erin Beeston is an historian, writer and heritage researcher. When she’s not juggling SEND parenting and the referral system, Erin’s making light of the situation through stand-up comedy.

Naomi Williams

Naomi is a documentary and portrait photographer born in Nottingham and based in Bristol. Her work has been published in the Guardian, BBC News, ITV News, Bristol in Stereo, LeftLion magazine, The Everyday Magazine and Fred Perry online.